Chapter 11: Creating Partnerships in Your Community

By Hope Wilson, MPH, RDN; Stephanie Grutzmacher, PhD; Lauren McCullough, MPH; Jennifer Parlin, MPH; Lily McNair, PSM, RDN

Introduction

Whether you are working in a clinical nutrition setting, providing nutrition education to small groups, or participating in a large public health nutrition campaign, it is essential to understand the community where you are working, engage the audience you are trying to reach, and develop and nurture partnerships within the community to successfully implement interventions that meet nutrition and health objectives.

This chapter describes methods for understanding the community with whom you are working and outlines the role that community engagement and partnerships play in implementing culinary medicine programs in those communities.

Social Determinants of Health

All people live within a larger societal context that shapes our health behaviors. The social-ecological model, which describes the different levels of influence on individuals, gives us a tool to understand the many complex factors that shape our health. To learn more about the social-ecological model, see chapter 1 of An Ecological Approach to Obesity and Eating Disorders by Greg Goines. These environmental conditions in which people are born, live, work, play, worship, and age are often collectively referred to as the social determinants of health (SDOH).

The Social Determinants of Health in Rural Communities Toolkit lists several SDOH that affect health and well-being, including1:

- Access to health-care services

- Access to nutritious foods

- Access to transportation

- Availability of safe streets and green space

- Education

- Employment and financial opportunities

- Housing quality and affordability

- Income and poverty

- Racism and discrimination

- Social support

In the interactive activity that follows, select the information symbols (i) to learn more about each level of the social-ecological model.

SDOH essentially are resources that are inequitably distributed among people, shaping inequitable health risks, functioning, quality of life, and outcomes. These inequitable outcomes are called health disparities. To reduce health disparities, culinary medicine initiatives must aim to address their root causes. One strategy for reducing health disparities is partnering with community organizations and members who have a range of experiences with and knowledge about SDOH, such as community planners, social service staff, teachers, childcare providers, economic development commissions, and housing authorities. Involving diverse community partners can help you effect upstream, sustainable changes in individuals’ environments and health.1 For more information on SDOH, see the following interactive activity and the suggested additional readings at the end of this chapter.

Understanding Your Community

Addressing differences in SDOH makes progress toward health equity. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “achieving this requires focused and ongoing societal efforts to address historical and contemporary injustices; overcome economic, social, and other obstacles to health and healthcare; and eliminate preventable health disparities.”2 According to Healthy People 2030, “SDOH have been shown to have a greater influence on health than either genetic factors or access to healthcare services.”3 Without understanding the greater context of individual people’s lives, health information given to them may be of no use, particularly if the SDOH they experience prevent them from making suggested changes.

To learn more about health equity, see the suggested additional readings at the end of this chapter.

Before you can successfully develop and implement a culinary medicine program within a community, it is necessary to understand that community so that the intervention is appropriate for the intended audience and considers the needs and assets of the community.

According to the CDC, a community is “typically defined by a geographic area,” however, a community “can also be based on shared interests or characteristics such as religion, race, age, or occupation.”4 Communities can be thought of as systems, networks of relationships, digitally mediated connections, or individuals’ sense of belonging and membership in groups or activities.5

To better understand the community you are working with, there are many different aspects to explore, such as history, demographic characteristics of the population, community leadership, community culture, existing organizations and institutions, economics, government/politics, social structure, infrastructure, commerce and industry, and attitudes and values.6

The methods for collecting information about the community you are working with depend on what information already exists, the type of information being collected, the scope of the intervention, and the specific audience for the intervention.

One way to learn more about your community is to conduct a community needs assessment. This process can include using existing information and collecting new information about the health, economic, and social statuses of the community, and resources in the community. Existing information collected by the government, other organizations, or researchers (often called secondary data) may include demographic characteristics of the population, vital statistics, rates of risk factors, and disease prevalence. These data sources are often collected using high-quality methods and represent the whole population in a community.

If needed information has not yet been collected, your community needs assessment could seek new information (often called primary data) using surveys, focus groups, interviews with community leaders, public meetings, asset mapping, observations, and other strategies. These sources of information are often highly valuable for representing the complexity and diversity within a community and capturing tailored or unique information.

Examples

The following are examples of secondary or existing data sources:

- Federal government websites such as the US Census, the National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Department of Health and Human Services.

- County Health Rankings & Roadmaps

- State and local government statistics

- Universities and other academic intuitions’ research studies

This list was adapted from Community Tool Box (chapter 3, section 1).

Community needs assessments should not focus only on what needs to be improved within a community. Gathering information about community resources and assets is important to understanding a community and informing culinary medicine programming. Furthermore, emphasizing these resources and assets can help ensure that you are using a strengths-based approach, which seeks a holistic treatment of both positive and negative aspects of underlying determinants of health, as well as opportunities and challenges in addressing those determinants.7 Asset mapping is a strengths-based strategy that can be used to capture the existing resources and assets in a community to help plan and implement interventions or programs that build upon what a community already has.

Before beginning a new community needs assessment, determine if one has been conducted recently, because many community organizations and government agencies regularly conduct needs assessments. For example, to receive accreditation from the Public Health Accreditation Board, state, tribal, local, and territorial health departments are required to complete and document a collaborative community health assessment at least every 5 years.8,9 Charitable hospital organizations are required to conduct community health assessments at least every 3 years to maintain their nonprofit 501(c)(3) status with the Internal Revenue Service.10

For more information about conducting a community needs assessment, review the process and strategies included in chapter 3 of the Community Tool Box from the University of Kansas Center for Community Health and Development. The CDC’s Public Health Professionals Gateway includes a guided index with resources and information for completing a community health assessment.

Watch this video from Maricopa County Public Health in Arizona to learn how it conducts its community health assessment:

Community engagement is another approach to better understanding your community. Each community has unique needs and assets related to community members’ health and wellness and the prevention of diet-related diseases. How to best support culinary medicine programs or education will vary depending on a community’s population, resources, needs, and priorities.10,11 When developing culinary medicine programs or initiatives in your community, it is important to integrate perspectives and insights from the community into the program’s goals and design. For example, if your geographic area is affected by limited access to affordable food, then you may need to work with the community to address the issue of food access to meet the needs and goals of your community.

The type of culinary medicine intervention or education would vary greatly for English-speaking, older individuals living alone in rural areas with low food access compared with large, Spanish-speaking families living in an urban area. In either case, working closely with the community enables you to better understand how your culinary medicine initiative fits with the population’s circumstances and context.

The International Association for Public Participation’s Spectrum of Public Participation describes a continuum of community engagement using the following levels: inform, consult, involve, collaborate, and empower. Each level corresponds to different goals and activities, ranging from informing the community of problems and solutions to empowering the community to make final decisions about implementation.

The process of community engagement can be rewarding; however, there are many factors health professionals should consider when engaging with communities. At the University of Arizona, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed) program, from the School of Nutritional Sciences and Wellness, collaborated with the Community Research, Evaluation, and Development (CRED) team from the Norton School of Human Ecology to develop a series of 7 interactive, online learning modules called the Community Engagement Training Series.

Importance of Community Partners

Culinary medicine seeks to help individuals achieve proper nutrition to help prevent or manage chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. As mentioned previously, lack of access to nutritious foods, limited food preparation experience or skills, and lack of nutrition information are among many systemic and individual barriers to nutrition. Because of the complexity of these challenges, there is no single policy, government entity, or organization that can address them alone. By working with other community leaders, organizations, agencies, and individuals, the work is spread out among multiple partners, each with their own strengths, audience, and areas of expertise to work toward shared goals but in different spheres of influence and addressing different SDOH.

Working With Community Partners

The success of community partnerships is often the key to the success of community programs. Community organizations are ideal partners for developing and sustaining community programs because they offer invaluable insight and experience with a wide range of populations that live in a community. Building community partnerships can also help effectively and efficiently provide programs while strategically using time and resources, in addition to building strong networks that lead to long-term, sustainable change.12 Culinary medicine offers a unique opportunity to synergistically work with a variety of different types and sizes of businesses and organizations within the community.

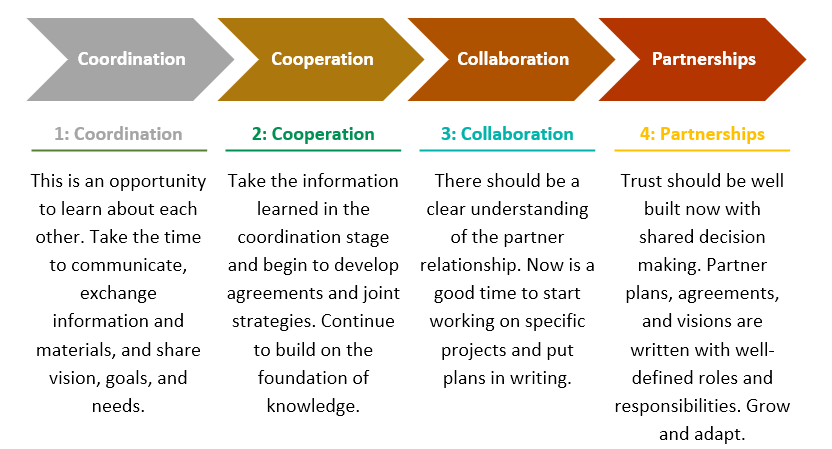

Partnerships may exist in different stages of collaboration. Some partnerships are informal collaborations between organizations, whereas others are formal contract agreements.12 The Partnership Continuum, outlined in Figure 11.5, describes the different stages of building a community partnership. It is important to note that not every collaboration will end in a full partnership, but each stage is important and can result in beneficial outcomes and shared information.12

Figure 11.5. Partnership Continuum12

5 Steps for Working with Community Partners

- Identify and engage potential partners. Identify interested parties in the community and initiate conversations to determine community engagement potential.

- Establish relationships and build trust. After identifying and engaging with potential community partners, establish collaborative relationships founded on mutual trust and respect.

- Clarify goals and objectives. Identify at the start each partner’s goals and objectives, to develop a shared process. Determined mutually agreed-upon standards for achieving goal.

- Implement mutually beneficial partnerships. Choose a partnership that will benefit both organizations and the community. Be flexible and practice consistent, clear communication.

- Establish structure for governance. Develop an equitable decision-making structure and establish governance, procedures, and ground rules. Commit to transparency to maintain trust.

Source: Engaging Your Community: A Toolkit for Partnership, Collaboration, and Action

The John Snow Research & Training Institute’s Engaging Your Community: A Toolkit for Partnership, Collaboration, and Action identifies 5 key steps to implementing a partnership with a community organization:

Step 1: Identify and engage potential community partners who will help build and sustain a community program.12 Three common types of community partnerships include those that are community based, government based, and faith based.12

When approaching potential community partners, it is helpful to do some research in advance. Make notes of the organization’s mission, vision, contact persons, and current programs. This will help better prepare you for approaching potential partners, because you will have a better idea of the organization’s needs and goals, which, in turn, will help you identify areas where the proposed community program can help support the organization.

After developing a list of potential partners, develop a plan for reaching out to them. Communication methods may differ depending on the organization but can include networking, emails, and phone calls. It is helpful to have a sample letter and a 1-minute “elevator pitch” that introduces you, provides a brief description of the proposed program, and explains why the proposed program can benefit the community partner and how the community partner can be involved. Also, provide contact information and proposed times and/or dates to discuss further, because the next stage often involves a partner meeting.

Step 2: Establish relationships and build trust with community partners, who may be seen as subject matter experts and opinion leaders.13 This step is essential to gain insight and better understanding of the community’s concerns and priorities. Those who live and work within a community are the best to identify the needs and the assets of knowledge of the community to effectively develop a relevant, community-specific program. Review with partners the resources that already exist and identify what may be used and what materials still need to be developed.

Identify how community partners can take an active role in the program, from development and promotion to implementation and maintenance. Now is also a good time to determine what your partners’ capacity is to help support the community program and work with the team, so as not to strain the community partners or hinder the implementation of community programs.13

Step 3: Clarify goals and objectives at the start of the program and continually evaluate them throughout the process.12 Be clear about intentions and goals for the proposed community program. In the case of culinary medicine, the community partner must understand what is expected to implement both culinary and nutrition education aspects. Make sure community members can honestly share their opinions; it is essential to make sure the partner feels heard and that the community voice is respected and represented.2

For a community program to be successful, goals and objectives should be mutually decided upon to develop a strong shared purpose and common agenda. Before implementing, it is also a good practice to develop shared parameters for measurement of success.13 In developing these parameters, it is important to also establish the roles and responsibilities of each partner to avoid or minimize confusion.13

Step 4: Implement a mutually beneficial partnership. The type of partnership will be based on the ability of each organization to commit time and resources.12 Therefore, it is critical to maintain clear and consistent communication.13 Communications must be timely and transparent, willing to address any concerns or barriers, as well as provide accountability.13 Ensure that each partner understands their individual roles and responsibilities as the partnership develops and schedule regular check-ins to assess progress, identify areas for improvement, and note successes.13

Step 5: Establish a structure for governance as the partnership and program continue to develop.12 This includes developing written ground rules at the initiation of a community partnership but allowing for dynamic procedures and governance that are adaptable as programs and partnerships grow and develop. A shared structure of governance ensures that each community partner’s voice is heard and that partners can participate in shared decision making.12 Transparency is essential for decisions regarding budget, resource allocation, adaptations to community programs, and opportunities for program growth.12

Collective Impact

The collective impact framework is the commitment of various actors or partners from different sectors to a common agenda to support positive outcomes to a social problem at scale. In this case, the barriers to a nutritious diet are many, and the solutions will require many partners to collaborate to solve this complex problem.

Five conditions are associated with the relative success of collective impact collaborations. These are described in the following text box.

5 Conditions for Collective Impact Success

- Common agenda: All participants share a vision for change that includes a common understanding of the problem and a joint approach to solving the problem through agreed-upon actions.

- Shared measurement: All participating organizations agree on the ways success will be measured and reported, with a short list of common indicators identified and used for learning and improvement.

- Mutually reinforcing activities: A diverse set of partners, typically across sectors, coordinate a set of differentiated activities through a mutually reinforcing plan of action.

- Continuous communication: All players engage in frequent and structured open communication to build trust, assure mutual objectives, and create common motivation.

- Backbone support: An independent, funded staff dedicated to the initiative provides ongoing support by guiding the initiative’s vision and strategy, supporting aligned activities, establishing shared measurement practices, building public will, advancing policy, and mobilizing resources.

Source: Based on Kania and Kramer.14

The following case study provides some suggestions for potential culinary medicine collaborators to engage and support a collective impact model in your community. It also explains how the 5 conditions for collective impact success were met to build healthy communities in Cochise County, Arizona.

Case Study on Collective Impact:

Building Healthy Communities in Cochise County

In 2018, the Legacy Foundation of Southeast Arizona awarded strategic grant funding to a community collaborative in Cochise County, Arizona, to expand and support county-wide health efforts with a focus on healthy foods access, nutrition, and active living. The grant was awarded to community partners that included University of Arizona Cooperative Extension, Cochise County Health and Social Services, Cochise County Superintendent of Schools, and the Community Food Bank of Southern Arizona. The Family, Consumer and Health Sciences agent for Cochise County Cooperative Extension was selected to be the principal investigator on the grant, and the evaluation specialist and lead of the CRED team within the Norton School of Human Ecology at the University of Arizona was selected to lead the evaluation.

The project, Building Healthy Communities (BHC), generated 3 main goals stemming from the county health assessment:

- Increase the community’s capacity for healthy change through leadership and collaboration.

- Increase the capacity of and access to the food system to reduce disparities in food security and nutrition in the county.

- Support the health and wellness of community youth through expanded school health initiatives.

These goals were approached from within a collective impact framework, which is a structured and formalized method of collaborating that includes the following core conditions:

- A common agenda, shaped by collectively defining the problem and creating a shared vision to solve it. This was established by forming community groups within each of the town centers and an overall committee and coordinator that ensured that the direction of the community groups focused on the 3 goals. The partners were included in the process to ensure that their efforts also focused on the same goals.

- Shared measurement, based on an agreement among all participants to track and share progress in the same way, which allows for continuous learning, improvement, and accountability. The University of Arizona CRED team led the evaluation efforts, and data were shared with the community groups and other interested parties to evaluate progress.

- Mutually reinforcing activities, integrating the participants’ many different activities to maximize the result. The community groups, community leadership, and other interested parties focused their efforts to address the common goals.

- Continuous communication, which helps build trust and forge new relationships. The community groups were updated about progress at a monthly county meeting. Partners were provided updates at meetings and through email and social media. Attending meetings or community events, meeting with members of the community who were in food service and food production, meeting with community members—basically, going anywhere there were people, and talking to them—helped to continually make new community connections.

- A “backbone support” team, dedicated to aligning and coordinating the work of the group. University of Arizona Cooperative Extension staff served as the backbone team and was tasked with coordinating the work of the initiative.

As more groups use a collective impact framework, they have been adding to these principles. From their experience with BHC, the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension staff found that the following additional principles are imperative to the success of this project: growing leadership, engaging community members, and centering equity.

The Cochise Community Leadership Academy (CLA) was formed to grow new leadership to practice the collective impact model. The CLA curriculum was initially adapted from the Arizona Community Training, a training curriculum developed by University of Arizona Cooperative Extension faculty and intended to promote personal, grassroots, and civic leadership in emerging community leaders. The training is designed to develop leadership from within communities to focus on emerging needs of the community and, ultimately, produce policy, systems, and environmental changes or other significant outcomes.

The ongoing collective impact work is strategic and straightforward in Cochise County, where partners come together for recurring half-hour calls during which they move through strategic plans step by step to ensure that they are making timely progress on their agreed-upon tasks.

The BHC project continues to build on its past successes, which are outlined in the summative report of its first 3 years of funded work. Outcomes from each BHC goal are highlighted in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1. Highlighted Outcomes of BHC’s Collective Impact Model

|

Goal |

Outcomes |

| Increase capacity for healthy change through leadership and collaboration. | Five new Healthy Community Committees (HCCs) formed, for a total of 11 HCCs.

Ten HCCs created vision and mission statements and 5 held strategic planning sessions. Six HCCs applied for and received additional funding, bringing more than $1 million to Cochise County communities. |

| Increase the capacity of and access to the food system to reduce disparities in food security and nutrition in the county. | Total amount of food, foods selected according to Feeding America’s “Foods to Encourage” framework, and the amount of fresh fruits and vegetables all increased by more than 50% over the first 3 years of the initiative.

Tripled the number of Produce on Wheels With-Out Waste (P.O.W.W.O.W) sites in the county. |

| Support the health and wellness of community youth through expanded school health initiatives. | Nearly 500 fifth- and sixth-grade students participated in a youth survey aimed at understanding attitudes and behaviors related to fresh fruit and vegetables, water, sugary drinks, physical activity, and screen time.

Eight new food pantries were established by BHC via local schools and communities. |

For the full 2018-2021 report, please refer to the Cochise Building Healthy Communities website.

Key Takeaways

- In developing a culinary medicine program that positively influences the health of those being served, it is essential to understand the community that is being reached. Community needs assessments, asset mapping, and community engagement are valuable tools that can be used to better understand communities.

- Community engagement is used to cultivate the buy-in of those being served, understand their priorities, and understand how they view their own communities. It is also important when working in communities not to focus only on the needs and gaps but also build upon the strengths, assets, and opportunities that already exist in the community.

- Many factors affect health other than individual choices or preferences. Interventions that address social determinants of health and target multiple levels of the social-ecological model help improve health equity.

- To make lasting change within communities, partnerships can help increase reach and work in different spheres of influence to influence not only individual health behaviors but the systems, environments, and policies in which individuals live.

- Partnerships can be developed at different levels of engagement. Using the collective impact framework, working with others in the community can be mutually beneficial to all organizations while also effecting change.

Suggested/Additional Reading

- Community Tool Box (Center for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas)

- What Is Health Equity? (CDC)

- Extension’s National Framework for Health Equity and Well-Being (Connect Extension)

- Social Determinants of Health (Healthy People 2030)

- Social Determinants of Health in Rural Communities Toolkit (Rural Health Information Hub)

- Community Engagement Learning Modules (University of Arizona SNAP-Ed Community Engagement Training Series)

References

- Rural Health Information Hub. Social Determinants of Health in Rural Communities Toolkit. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/sdoh

- Health equity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/index.html

- Social determinants of health (SDOH). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. January 17, 2024. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/about/priorities/why-is-addressing-sdoh-important.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Community needs assessment: a step-by-step guide. Accessed November 25, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20240916222211/https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/fetp/training_modules/15/community-needs_pw_final_9252013.pdf

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Principles of community engagement. In: Principles of Community Engagement. US Department of Health and Human Services. Last reviewed June 25, 2015. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/community-engagement/php/chapter-1/concepts-community.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_concepts.html

- Hampton C, Haven C. Understanding and describing the community. In: Community Tool Box. KU Center for Community Health and Development, University of Kansas; chapter 3. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/assessment/assessing-community-needs-and-resources/describe-the-community/main

- Global health equity. Using a global public health equity lens. In: Guiding Principles for Global Health Communication. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; May 15, 2024. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/global-health-equity/php/publications/equity-lens.html

- Public Health Accreditation Board. Standards & measures for initial accreditation. Version 2022. 2022. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/Standards-Measures-Initial-Accreditation-Version-2022.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Community Health. A Practitioner’s Guide for Advancing Health Equity: Community Strategies for Preventing Chronic Disease. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dnpao-state-local-programs/php/practitioners-guide/index.html

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health

- McCullough L, Leih R, Wash M, Farrell VA. Community engagement for Cooperative Extension: what is community engagement? Cooperative Extension, The University of Arizona. October 10, 2023. Accessed November 25, 2024. https://repository.arizona.edu/bitstream/handle/10150/671200/az2023-2023.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- John Snow, Inc. Engaging Your community: a toolkit for partnership, collaboration, and action. January 2012. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://publications.jsi.com/JSIInternet/Inc/Common/_download_pub.cfm?id=14333&lid=3

- Shakespeare J, Mizota M, Martinez R, Daly H, Falkenburger E. Fostering partnerships for community engagement. October 2021. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104935/fostering-partnerships-for-community-engagement_0.pdf

- Kania J, Kramer M. Collective impact. Stanf Soc Innov Rev. 2011;9(1):36–41. https://doi.org/10.48558/5900-KN19

H5P References

- McCloskey DJ, McDonald MA, Cook J, et al. Chapter 1: Models and frameworks. In: Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. NIH Publication No. 11–7782. US Department of Health and Human Services; December 6, 2018. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/community-engagement/php/chapter-1/models-frameworks.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_models.html

- American College Health Association. Ecological model. Accessed November 25, 2023. https://web.archive.org/web/20240529093645/https://www.acha.org/HealthyCampus/HealthyCampus/Ecological_Model.aspx

- Healthy People 2030. Economic stability. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/economic-stability

- Healthy People 2030. Reduce household food insecurity and hunger—NWS-01. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/reduce-household-food-insecurity-and-hunger-nws-01

- Healthy People 2030. Education access and quality. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/education-access-and-quality

- Healthy People 2030. Health care access and quality. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/health-care-access-and-quality

- Healthy People 2030. Neighborhood and built environment. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/neighborhood-and-built-environment

- Healthy People 2030. Social and community context. Accessed October 20, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/social-and-community-context

The process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people. Source: Principles of Community Engagement, 2nd Edition

A way of thinking that “understands health to be affected by the interaction between the individual, the group/community, and the physical, social, and political environments.” These nested levels organize many factors that affect health to help communities “develop approaches to disease prevention and health promotion that include action at [these] levels.” Source: Principles of Community Engagement, 2nd Edition

The conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. Source: World Health Organization

Differences in which disadvantaged social groups such as the poor, racial/ethnic minorities, women, and other groups who have persistently experienced social disadvantage or discrimination systemically experience worse health or greater health risks than more advantaged social groups. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health. Achieving this requires focused and ongoing societal efforts to address historical and contemporary injustices; overcome economic, social, and other obstacles to health and health care; and eliminate preventable health disparities. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

A process to collect information to identify community gaps or needs that impact health and wellness as well as identify the strengths or community assets that can be used to build solutions to the issues considered a priority to the community. Source: Community Tool Box

A process of identifying and compiling a list of assets ("anything that can be used to improve the quality of community life") and organizing this information in a format, usually visually, that can be used to make improvements. Source: Community Tool Box

A commitment of various partners from different sectors to a common agenda that will bring about positive social change or solve a specific social problem. Source: Stanford Social Innovation Review