Chapter 12: Culturally Centered Approaches to Culinary Medicine

By Martina Cartwright, PhD, RDN; Lauren McCullough, MPH; Lucia Ramonet, MS, RDN, CNSC; Ashley Munro, MPH, RDN, CDCES; Hope Wilson, MPH, RDN

Student Contributor: Czarina Ojeda

Introduction

Food, diet, and culture are inextricably linked. Efforts to support a healthy eating plan must be grounded in an understanding and respect for the individual’s culture and its foods. Although the ideas about what is a “healthy” diet have been heavily influenced by Westernized ideals about what is or is not a healthy eating pattern, no single diet has proved best for all.

Indeed, genetics likely play an important role in food selection, preferences, and health outcomes by influencing sensory pathways that affect taste, smell, texture, and the brain’s reward response, as well as how people respond to specific nutrients. Local culture, environment, and family customs also influence food choices, dietary behaviors, and cooking and food shopping practices.

Consuming a wide variety of nutritious foods and beverages in the amounts recommended is a central tenet of healthy eating. However, evidence-based meal plans such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, and others recommended in the United States may not adequately include cultural foods. Cultural foods are strongly anchored to familial customs and passed down from generation to generation. Cultural foods, including dietary staples, often stem from regional preferences influenced by local crops or from past influences of different cultures living in the same location. These foods may also be integral to religious or ceremonial functions, often including specific food preparation methods and uses.

Many people connect with their heritage through the foods they eat. The tendency of health-care providers to recommend the removal of cultural foods from a person’s diet causes some individuals to struggle with making dietary modifications because they don’t know how or don’t want to exclude these foods. Understanding cultural foods in the context of meal planning, affordability, and accessibility is paramount to engaging individuals seeking to improve their nutritional health.

Culinary medicine works with clients to support the pursuit of a varied diet to take in adequate energy and essential nutrients within cultural preferences and traditions. Within all diets, opportunities can be found to make small changes compatible with a person’s culture and traditions that promote health. Small, culturally appropriate adaptations are easier for people to adopt and sustain, which is the key to achieving better health.

Culturally Centered Approaches to Culinary Medicine

Traditional nutrition counseling and community nutrition education have focused on modifying foods and behaviors to create healthy eating patterns using tools provided by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), including MyPlate, or others like the DASH diet.1-3 However, the healthy eating patterns described in these tools are modeled after Western culture and may not apply to culturally diverse populations.1-6

To effect dietary change among individuals with nutrition-sensitive conditions, nutrition and medical professionals must be able to engage with their clients on a personal level and to tailor nutrition care plans and education. Although there is increased interest in culturally tailored nutrition education interventions, there are few, if any, practical guides that empower nutrition professionals to develop and implement comprehensive culturally centric culinary medicine plans.

This chapter aims to provide nutrition professionals with an understanding of cultural foods in the context of applied culinary medicine and to describe specific culturally tailored nutrition strategies that can be implemented to address nutritionally sensitive diseases.7

Rethinking “Healthy” Eating

Search “healthy diet” on the internet and you’re likely to see images of carefully plated salmon, a green leafy vegetable, and a whole grain (see Figure 12.2). Such “healthy” dietary constructs are heavily influenced by Westernized ideals about what is or is not a healthy eating pattern. Definitions of healthy eating are variable, but central to all healthful eating constructs is consuming a wide variety of nutritious foods and beverages in the amounts recommended. The Healthy Food Pyramid, My Plate, DASH diet, and other meal plans recommend specific food groups to encourage the consumption of nutrient-dense foods and beverages designed to counter diseases.1-3 However, these meal patterns may not include cultural foods.4-7

Certain foods closely linked to cultural identity may be perceived as “unhealthy,” causing some ethnic minority subgroups to shun traditional foods and cooking preparation methods in favor of Westernized meal patterns. This phenomenon, known as dietary acculturation, has been identified as a chronic disease risk factor for Latinos in the United States.5

Another example, the Mediterranean diet, is widely accepted as an ideal diet. However, some researchers have noted that bias has historically shaped which diets are studied.6 For example, a PubMed search using the phrase “Mediterranean diet” yields more than 4 times as many results as searches using the phrases “traditional Chinese diet,” “traditional African diet,” and “traditional Mexican diet” combined.

Indeed, the Mediterranean diet recommends foods favored by Europeans and Americans, rather than foods of the region it purports to represent.6 Other critiques of the Mediterranean diet are the lack of affordability, emphasis on liquid oils, and that it’s not an appropriate substitution of other cultural diets. Thus, as is, the Mediterranean diet may not be a culturally appropriate dietary solution to prevent and manage disease. However, as with all standardized meal constructs, modifications can be made to be more culturally inclusive.4,6

What Are Cultural Foods?

Cultural foods are strongly anchored to familial customs and passed down from generation to generation. Cultural foods may stem from regional preferences influenced by local crops or from past influences of different cultures living in the same location. These foods may also be integral to religious or ceremonial functions, which often include specific food preparation methods and uses (Figure 12.3).

Regardless of culture, most meal patterns typically include a protein (e.g., meat, fish, legumes, nuts), a starch (e.g., potato, corn, breadfruit, rice, taro), and fruits and vegetables. The presence of the latter often is influenced by seasonality, locality, cost, and availability. Understanding cultural foods in the context of meal planning, affordability, and accessibility is paramount to engaging with individuals seeking to optimize their nutritional health.

Select the words and phrases that describe aspects of cultural foods:

Socioeconomic Factors Influence Food Selection

Income, education, and food access all play a role in food selection, cooking patterns, and portion size. These 3 factors generally affect racial and ethnic minorities more.8,9 As such, a tailored nutrition care plan should include evaluation of income, education, and food access, and it should explore ways to improve overall health without compromising cultural sensitivity.

Income and Food Access

Income can influence choices about the types of foods individuals purchase and consume regularly. Individuals with lower incomes tend to purchase and consume more energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, such as fast food and processed snacks, compared with individuals with higher incomes.10 More nutritious foods, such as fresh fruits and vegetables, lean meats, and whole grains, are often more expensive and may be out of reach for those with lower incomes.9 One solution is to encourage consumption of more affordable dietary proteins, such as beans, lentils, tofu, and eggs, which can be used in a variety of dishes.

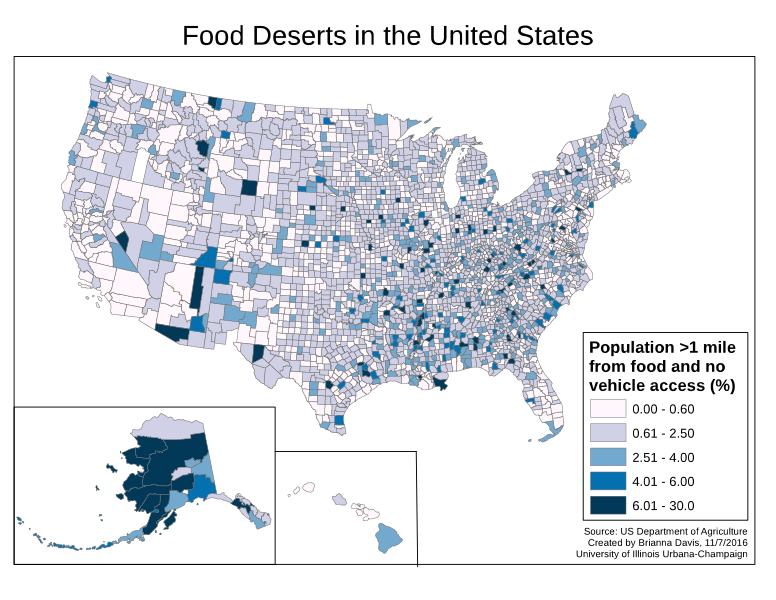

Adopting healthy eating behaviors is more challenging for those with lower incomes, and they are less likely to consume a healthy diet, even when healthy foods are available, due to a lack of knowledge about healthy eating and limited access to nutritious food options.11 As an example, people who live in low-access regions have limited access to nutritious foods because they either do not live close to a food market or have inadequate transportation to reach a market. Food deserts tend to affect people living in rural areas and/or urban areas lacking grocery stores (see Figure 12.4). Nutrition knowledge and education have been significantly associated with improved individual health status.12

The term food deserts has historically referred to regions with low access to affordable, healthy foods. However, the term food desert has been met with criticism because it carries negative connotations and does not adequately capture all factors related to food access. Efforts are being made to adopt alternative terminology, such as low-access region, to acknowledge diverse perspectives and facets of the issue.13 Therefore, the reader should be aware of both the historical term food desert and more inclusive terminology, such as low–access area.

Education

Education is also a significant factor that affects nutrition patterns, food accessibility, and affordability. Higher levels of education are associated with healthier eating patterns, because individuals with more education tend to have more knowledge about healthy eating habits.10 Higher education levels correlate with higher incomes, which can allow individuals to purchase healthier foods.

A 2009 Food and Research and Action Center study found that individuals with higher levels of education were less likely to experience food insecurity, which can negatively affect diet quality.14 Additionally, individuals with higher levels of education are more likely to have access to information about healthy food choices and cooking methods, which can further improve diet quality.15

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity, or the lack of access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food to meet needs, is a growing issue that affects millions of people worldwide, and disproportionately affects certain minority populations and cultures.16 It may culminate from a lack of resources (e.g., income) and food access.

Food insecurity contributes to nutritional deficiencies and poor diet quality. In a 2015 study, food-insecure Canadian households had a lower intake of calcium and magnesium when compared with food-secure households,17 suggesting food insecurity may limit access to and procurement of healthy foods, favoring low-cost, poor-nutrient foods to meet basic needs.12

Additionally, food insecurity has a bearing on weight status and chronic disease risk.18,19 Individuals who are food insecure are more likely to consume energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods, which can lead to weight gain and an increased risk for chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension.20 Food insecurity is also associated with stress and anxiety, which may affect eating behaviors such as overeating or making unhealthy food choices.21

Supporting Optimal Nutrition

There is significant evidence to suggest that socioeconomic factors have a significant influence on nutrition patterns. Education, income, and access to healthy food all play crucial roles in determining dietary choices and, ultimately, overall health outcomes. People from lower socioeconomic backgrounds often have limited access to nutritious foods, leading to a higher risk of malnutrition, obesity, and chronic diseases. Addressing these socioeconomic factors is a priority and integral to promoting healthier diets and improving overall public health.9,10,12 With this in mind, the nutrition professional can foster improvements in nutrition patterns and help reduce health inequalities through targeted, comprehensive, and culturally responsive nutrition education.

Cultural Food Staples

A staple (see Figure 12.5) is a food that comprises most of a population’s diet.22 Staples are eaten regularly, often daily, and supply most of a person’s energy and nutritional needs. Staples vary by culture and location and are typically plant-based foods (see Table 12.1). There are 50,000 edible plants in the world, but only 15 make up 90% of the world’s food energy intake.22 Rice, corn, and wheat make up two-thirds; other staples include millet, sorghum, and tubers (e.g., potatoes, cassava, yams, taro).

Tropical climates favor growth of starchy fruits such as plantains and breadfruit, whereas in parts of Africa and Asia, legumes (e.g., beans, lentils) are considered traditional foods. In regions where plants are scarce, such as in polar climates, meat and fish are staples.22

Table 12.1. Staple Foods and Dishes of Certain Cultures

|

Culture |

Staple foods | Staple dishes |

|---|---|---|

| African Diaspora | Rice, beans, tubers, okra, leafy greens, seafood, chicken, peanuts, squashes, plantains, fruits, and juices such as mango and guava | Soups, stews, chicken dishes, fish cakes, rice, vegetables platters |

| Mexican | Rice, beans, vegetables (e.g., onions, garlic, squash, corn, avocados), chicken, seafood, corn-based flour, spices such as cumin and cinnamon | Tortillas (flour and corn), tamales, ceviche, burritos, tacos, nopales, fajitas |

| Chinese | Rice, seafood, noodles, pork, spring onions, bok choy, ginger, bean sprouts, snow peas, soybean products such as tofu | Steamed dumplings, rice dishes, noodle dishes, mooncakes, soups, congee |

| American Indian (Native American) | Corn, beans, squash, pumpkins, peppers, tomatoes, yams, peanuts, wild rice, wild game (e.g., deer, buffalo, rabbit) |

Three sisters stew; grayish-blue bread called piki made by the Hopis; pemmican. Panocha is a traditional Native American cuisine dish. In New Mexico and southern Colorado, panocha is a pudding made from ground sprouted wheat and piloncillo (sugar). |

| Alaskan Native | Salmon, halibut, reindeer, seafood, wild blueberries, strawberries | Salmon dishes, muktuk (whale skin and blubber), akutaq (Eskimo ice cream) |

| Pacific Islander Hawaii and Samoa | Taro, sweet potatoes or yams, breadfruit, cassava, banana, plantain, pandanus, arrowroot | Poi, kalua pork, lau lau, breadfruit, dried fish |

| Caribbean Islands | Beans, rice, coconut milk, green bananas, plantains, breadfruit, cassava, dasheen (taro), peppers, seafood, tropical fruits (e.g., mango, papaya, pineapple), okra | Cou cou, crab, and callaloo |

| Eastern Indian | Rice, wheat, millet, pulses, dairy, vegetables, spices, beans, fruits | Machher Jhol, dalma |

The population often reflects the local demographic fingerprint of the region in which health providers practice. Determining the predominant culture of the town, city, or county of practice may assist in the development of cultural competency.

The state of Arizona is demographically 1 of the most diverse in the United States.23 As of 2022, among the more than 7 million residents, 53.2% identify as White, 32.3% as Hispanic or Latino, 5.4% as Black or African American, and 5.3% as American Indian or Alaska Native.22 The percentage of people born outside the United States and reside in Arizona from 2017 to 2021 was 13%.23

Arizona’s population is also age diverse, with nearly one-fourth under the age of 18 years and 18.3% over the age of 65 years; more than 400,000 military veterans call Arizona home and more than 50% of Arizona’s population is female. Each city in Arizona has a unique cultural fingerprint, with diversity of ethnicity and age varying significantly within cities, towns, and neighborhoods.24

Nutrition professionals in Arizona are encouraged to learn more about local diversity by visiting the University of Arizona’s Community, Research, and Evaluation Development Resources webpage, especially noting the “secondary data resources,” including the “existing data resources handout.”25 Also, local hospitals and organizations may have demographic data available that will reveal a bit more about the population in a specific area. Understanding the surrounding community is key to developing nutrition care tools tailored to the primary population in the region. Another method of getting to know your local culture is through community engagement, as referenced in chapter 11.

Cultures in Arizona

Arizona’s culinary heritage is richly influenced by local crops as well as Hispanic-Latino and American Indian cultures, giving rise to the state’s reputation as the home of some of the oldest documented food traditions in North America.25 Arizona became the 48th state in 1912, but cultivation of corn and squash in the region dates back 4,100 years.26

In Arizona, crop production differs by location, and despite modernization, today’s local farmers maintain tradition by growing more than 160 heirloom varieties of fruits, grains, and vegetables that were available at the time of statehood.26 Arizona is home to numerous varieties of cacti, lending to long-held traditions of harvesting saguaro cactus fruit and prickly pear fruit to make syrups, candy, and fruit spreads. Figure 12.6 shows prickly pear fruit prepared at different degrees of ripeness.

Local culture, environment, and familial customs influence food choices, dietary behaviors, and cooking and food shopping practices. Genetics also may play a role in food selection, preferences, and how people’s bodies respond to specific nutrients. Nearly 500 genes influence food preferences, with several genes influencing sensory pathways that affect taste, smell, texture, and, in turn, the brain’s reward response (Figure 12.7).27

Defining cultural awareness from the standpoint of the nutrition professional sets the foundation for creating an inclusive and welcoming nutrition education environment.

Embracing Cultural Foods

Many people connect with their heritage through the foods they eat. Therefore, individuals may be hesitant to seek dietary advice from a nutrition professional for fear of being advised not to eat core cultural foods. However, efforts have been made to address and include culturally tailored dietary modifications for those with nutrition-senstive diseases through the development of cookbooks and culture-centric nutrition intervention programs, thus reducing the tendancy of health-care providers to recommend removal of cultural foods altogether.28-30 Cultural influences on dietary self-management of diseases such as diabetes also include social aspects of eating.28–30

Research has found that certain dietary changes may compromise the taste of traditional food, and there are concerns that making changes in diet will exclude them from familial meals, thus reducing the joy of dining as a family, a value deeply held by some cultures.28–30

Clinical Pearl: Many traditional foods are rich in nutrients and tradition, which are part of a balanced and sustainable approach to nutrition.31 When engaging with an individual seeking nutrition advice, it is important to understand if their current diet includes staples and, if so, to determine what those staple foods are, how they are prepared, the frequency of consumption, and the portion size. Reassuring the client that staple foods will not be eliminated may ease concerns about drastic dietary changes.

The USDA’s Dietary Guidelines for Americans are a gold standard for nutrition guidelines and recommend including cultural foodways.32 However, the MyPlate food recommendations skew toward North American preferences.1,32,33 For example, grains in MyPlate include bread, pasta, cereals, rice, and tortillas and lack foods such as taro, breadfruit, and other starchy foods considered “cultural foods.” Similarly, the widely recommended DASH diet discourages refined carbohydrates, such as white rice; however, rice is a staple of many culturally centric diets.22,26,29,34

The USDA has made advances in providing resources dedicated to American Indian and Alaska Native Communities, including My Native Plate, which depicts balanced meals with reasonable portion sizes and sample meals with traditional foods.34 However, tools for other cultures are lacking.

Clinical Pearl: Instead of using the traditional dietary guidelines or established meal plans verbatim, modify them according to the person’s cultural and personal preferences. For example, find out what grains the person eats daily and incorporate those into the overall meal plan. Determine their favorite fruits and vegetables: ask how they are prepared, then consider what could be added to increase nutritional quality or satiety. Through active listening and cultural sensitivity, a tailored plan can be created.

Cooking Traditions and Methods

Cooking traditions and methods are as varied and diverse as the many nations and ethnicities from which they originated. Many cultures include nutritious dishes prepared with healthy ingredients (see Table 12.1) and cooking methods. For example, in Mexico and the Global South, dishes such as ceviche contain fish that has been prepared by marinating it in citrus such as lemon or lime juice. Steam is often used by many cultures as a primary cooking method. In Mexican culture, tamales are prepared by steaming them. Dumplings originated in China during the Han dynasty and today are cooked by various methods, including steaming, boiling, steam frying, or deep frying.

When working with a community member or individual who expresses an interest in modifying a cultural recipe to reduce sodium, increase fiber, or make other modifications for disease prevention or management, it is important to be prepared with culturally appropriate suggestions, or to know what resources exist to guide modifications. In the example shown in Figure 12.9, dumplings could be steamed instead of fried to reduce saturated fat. Another consideration is the practical impact such a modification would make. For example, if a patient rarely consumes a particular food or if the portion size is routinely small, nutritional modifications in the name of “health” would have minimal impact on overall nutrition quality, and may, in fact, impair rapport with the patient.

As mentioned, white rice is a staple in many ethnic diets (see Table 12.1); however, it tends to be lower in nutrients and fiber than brown rice. Brown rice may be swapped for white rice, but if this substitution is not acceptable to the individual due to tradition, preference, or cost, dietary instruction encouraging reduced portions of white rice is recommended. Other ways to help individuals make gentle dietary changes is to suggest fiber-rich lentils or unpeeled whole potatoes as occasional substitutes for low-fiber choices (e.g., peeled potatoes). Also, modifying cooking methods or recipes using high-fat condiments, sauces, and or saturated fats is recommended. For example, collard greens are often prepared with bacon fat; suggest preparation with a mono- or polyunsaturated fat (e.g., olive oil) as an alternative.

Clinical Pearl: Understanding how foods are cooked and which ingredients are used to make recipes or meals can help nutrition professionals make alternative suggestions while preserving cultural integrity. Ask about the use of cooking oils, fats, and added sugars in traditional recipes and dishes. Then, make suggestions on how to swap out less optimal choices for more nutrient-dense alternatives.

An Example of Cultural Sustainability: Reuniting the 3 Sisters

For centuries, Native Americans grew corn, squash, and beans together in plots (Figure 12.10). The term “3 sisters” describes how the 3 plants thrived when cultivated together, the planting and harvesting of these Native American staples is making a comeback. Planting corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers produces synergistic growing conditions favoring these plants. Corn stalks create a trellis for the beans to climb while the beans stabilize corn stalks against the high winds. Corn and beans grow well together because bacteria on the bean plant’s roots draw in nitrogen from the air, encouraging growth of both plants. Squash provides essential ground cover, preventing weeds and preserving water, and sunflowers around the edge serve as natural fencing and attract pollinators. Some squash vines have thorns that discourage deer, racoons, and other animals from eating crops.35

Native Americans are disproportionately affected by high rates of obesity and diabetes.36 By revisiting and reinitiating farming practices of their ancestors, access to cultural food staples may expand and help reduce rates of these diseases.31,35-37

Cultural Humility and Competence

Cultural humility involves understanding the complexity of identities and cultivating conversations that attempt to understand a person’s identities related to race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and other factors.38 A culturally competent provider needs to have knowledge and awareness of health-related beliefs, practices, and cultural values of diverse populations; illness and diagnostic incidence and prevalence among culturally and ethnically diverse populations; and treatment efficacy and safety data for diverse populations.38

Certain nutritionally sensitive diseases disproportionately affect many ethnic minorities, due to several factors, including somewhat modifiable factors such as environment and lifestyle choices but also nonmodifiable factors such as genetics and social-systemic constructs fostering health disparities.39 Diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and obesity may be managed, in part, through nutrition education and strategies. However, successful nutrition intervention requires a tailored approach attentive to cultural food aspects.37

In Arizona, the 2 most common and costly chronic highly nutrition-sensitive diseases are heart disease and diabetes.38 Poor nutrition and lack of physical activity are the most frequently cited risk factors.40 However, both factors are influenced by environmental limitations to nutritional variety (e.g., low-access areas), access to healthier food options, and access to locations conducive to physical activity.41

In 2019, Banner Health Banner Thunderbird Medical Center (Maricopa County) undertook a needs assessment survey to identify and understand community health needs. Surveys were administered to 152 professionals who were identified as health or community experts familiar with target populations and demographic areas in Maricopa County.42 The survey asked respondents about factors that would improve quality of life, most important health problems in the community, risky behaviors of concern, and their overall rating of the health of the community.

When asked to rank the 3 most important risky behaviors seen in the community, the top 5 answers included being overweight (57.2%), alcohol abuse (42.8%), poor eating habits (39.5%), drug abuse (35.5%), and lack of exercise (34.2%). The report also identified perceived lack of cultural competency and health literacy as barriers to health improvement and chronic disease management. The Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease for Arizona found that 62% of the population is overweight or obese, with 40% eating fewer than 1 fruit per day and 24% eating fewer than 1 vegetable a day. It’s thought that these risk factors contribute, in part, to higher rates of heart disease and diabetes in the state.43

Addressing Nutrition-Sensitive Diseases

Heart Disease

Heart disease ranks as the number 1 cause of death in Arizona.44 People can help prevent heart disease by understanding the risks and taking simple steps to address them. Among these steps is modification of nutritional habits. Helping individuals at risk for cardiac ailments to be mindful of the type and amount of dietary fats found in foods and fats used in cooking is essential to help reduce cardiac disease mortality and morbidity. Encouraging plant-based, fruit- and vegetable-rich meal plans, while being aware of economic constraints that prevent or limit purchasing ability, is key to help those with cardiac risk factors to make lasting change.45

Clinical Pearl: When providing nutritional counseling to individuals with cardiac risk factors, ask about their cultural foods and recipes. Having a conversation about recipes and typical cooking methods can help you and the individual make collaborative changes that encourage consumption of foods with known cardiac benefits, such as fruits, vegetables, high-fiber grains, lean proteins, low-fat dairy, and use of poly- or monounsaturated fats.45

Diabetes

Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States.46,47 Although diabetes affects people of all cultures, races, and ethnicities, higher rates are reported among Hispanics, Black people, Asian Americans, and American Indians and Alaskan Natives.46

It is important to recognize that rates of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) vary within cultures as well. For example, South Asian, Filipino, Pacific Islander, and certain Japanese groups have a higher prevalence of T2DM compared with the East Asian subpopulation (i.e., populations originating from China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan).48–51

Body weight is a strong predictor of diabetes risk.52 Chronic elevated blood glucose level is associated with increased risk of cardiac and renal comorbidities.46,47 Stabilizing one’s blood glucose level throughout the day is critical to managing diabetes. This is done through a combination of meal planning, meal timing, and portion control. Educating those with diabetes or diabetes risk factors about portion size and focusing on limitation instead of elimination will encourage meaningful dietary change. However, many cultures view special diets as disruptive to social harmony and burdensome to others.51,53

For example, among East Asian individuals with T2DM undergoing nutritional counseling, dietary recommendations did not always align with their beliefs of food as medicine or as a source of balance in life or healing. Chinese American, Korean American, and other subpopulations of Asian Americans found it difficult to adapt to T2DM dietary modifications because doing so caused them to feel distanced from familiar and shared cultural food habits and practices.30,48–51 Chinese American patients noted that rice is a vital food, both physically and symbolically, and to remove such a critical cultural staple from their diet is difficult.30,48–51 For many Asian cultures, dietary management and food preparation are the responsibility of the patient and the spouse or partner.30,51 Therefore, including significant others in conversations about dietary change, food preparation, and even meal timing is essential to supporting the individual on their journey to make dietary changes.

Check your understanding with this case study:

Significance of Mealtimes

Commensality is central to many cultures.54,55 Mealtimes offer opportunities for people to engage in eating and socialization. For children, mealtimes can be a time of apprenticeship, where they can actively observe and participate in mealtime customs and traditions. Mealtimes vary within and across social groups in relation to participation, setting, duration, meal items, meal sequence, and food symbolism. Regardless, commensal meals are a time for participants to master cultural knowledge and practices associated with shared gatherings. A key tenet of the Mediterranean diet is the concept of conviviality, which involves enjoying family meals as a way to promote healthy eating.56

Clinical Pearl: A goal in developing culturally centric diabetes meal plans is to limit but not eliminate foods and food groups and to understand about timing of meals. Learning about the food staples included in the individual’s daily meal plan, their usual portion size, and the time of day when meals are eaten and with whom can help the nutrition professional design comprehensive and mutually agreeable meal plans. When culturally appropriate, nutrition counseling should involve both patient and their partner and supporters and strive to preserve cultural integrity while limiting the perceived social disharmony often caused by special diets.

Test your understanding with this crossword puzzle:

A Call to Action:

Become a Culturally Competent Nutrition Professional

Culturally tailored nutrition education efforts have resulted in effective dietary change among those seeking to optimize their nutrition patterns. Providing single recipes or cooking demonstrations as part of multicomponent intervention to decrease meat consumption among Latinos and other populations has increased purchasing of produce.57 The positive results from these dietary interventions, along with culinary medicine approaches, are low-cost and high-impact initiatives to improve dietary attitudes, culinary skills, and dietary intake, and can increase self-efficacy and competence with regard to nutrition knowledge.30,33,55,56 Although these interventions have produced positive results, there is a need for broader cultural competency, because better diet adherence, improvements in disease management, and lower chronic disease burden were found when cultural elements are incorporated.34

So how can one enhance cultural competency in everyday nutritional education and counseling? Start by expanding your knowledge of the local community in which you practice. What are the demographic, socioeconomic, and food-shopping characteristics of the community? What are the most common chronic diseases affecting the community?

Next, identify resources to help you learn more about the predominant cultural foods and locate any nutritional counseling resources. Develop some screening questions to learn more about how an individual’s food selections may be influenced by cultural aspects and socioeconomic factors, and query your clients about their cultural food preferences. Use the Prepare-Engage-Respond model explained in the next section to address key areas with your clients or patients.57

Examples of Cultural Nutrition Counseling Questions

- What foods do you typically eat every day?

- Are there any foods you “can’t live without”?

- Are there occasions, such as holidays or events, for which you prepare special dishes? If so, what are those dishes? What are the ingredients?

- What are some cooking methods you use every day? For example, do you fry? Bake? Steam? Boil?

- What 2-3 foods do you consume nearly every day?

- How many fruits and vegetables do you eat every day?

- How do you prepare fruits and vegetables?

- Do you have challenges buying food?

- Are your food selections influenced by concerns about wasting food? For example, do you avoid buying fresh fruits and vegetables because they may ripen too quickly?

- Who primarily prepares meals in the household?

- What is your typical meal pattern—when do you eat (time of day)? Where (home, work)? With whom do you eat these meals (family, friends)?

- What is your greatest concern about potentially changing your meal patterns?

Prepare-Engage-Respond

There are many ways for nutrition professionals to engage with clients of all cultures. Prior to an encounter with an individual, whether as an outpatient or inpatient, here are ways to prepare, engage, and respond to them.56

Prepare

- Learn about the community and the individual’s culture before interacting.

- Take the time to familiarize yourself with foods considered staples of the culture of the client and/or the community.

- Gather available, culturally applicable dietary resources that may assist with nutritional counseling at the time of the appointment.

- Reach out your institution’s language translation services; if you are in private practice or lack institutional services, contact a local medical interpreter in advance of the appointment; these services are typically available for a small fee, either for in-person or telephonic translation. Translation services are free if associated with a hospital or other organization.

Engage

- Ask questions about family traditions, recipes, and ceremonies.

- Query about the type of foods eaten, as well as quantity and environment, time of day meals are typically eaten, and with whom.

- Encourage clients to share their health-related values and beliefs.

- Have clients describe examples of how culture plays a role in eating habits.

- Ask about traditional spices used in dishes.

- Actively listen to what is important to the individual about their concerns or hesitancy to make dietary or meal pattern changes.

- Involve other family members or supporters in dietary modification discussions.

Respond

- Provide tips on how to involve family when preparing meals.

- Provide reasonable and practical modifications to traditional recipes.

- Encourage the use of traditional foods with attention to portion sizes.

- Include tips on incorporating traditional flavors using lower sodium or reduced-fat options.

- Give positive feedback regarding dietary changes.

Taking a Mindful Approach

Creating cultural humility and practicing cultural competency in the context of the application of culinary medicine are a recipe for success. The act of bridging these 2 elements is largely dependent on the practitioner’s motivation to seek resources to expand understanding of cultural food preferences, choices, and beliefs of the individuals they encounter.

Although the medical literature may be lacking evidentiary support of best practices on how to enhance nutritional cultural competency, the best source of this knowledge is the individuals themselves, who can offer the practitioner a firsthand accounting of the food traditions and cultural aspects that influence their nutritional behaviors. By partnering with those seeking nutritional guidance, the nutrition professional can optimize personal development toward the goal of offering culturally centered approaches to culinary medicine.

Key Takeaways

- Many popular meal constructs are skewed to Western dietary patterns and preferences but can be modified to be more culturally inclusive.

- Cultural foods can and should be part of optimal nutrition plans.

- Environmental, socioeconomic, and cultural factors influence dietary customs and/or behaviors that affect nutrition patterns, food selection, food preparation, food purchasing, meal timing, and commensality.

- Using the best available science to foster cultural humility and competency through thoughtful and engaging nutrition invention strategies is a path to help optimize health outcomes in ethnically diverse groups while maintaining cultural integrity.

References

- What is MyPlate? 2022. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/what-is-myplate

- Description of the DASH eating plan. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Updated December 29, 2021. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/education/dash-eating-plan

- Healthy Eating Pyramid. Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. 2008. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/healthy-eating-pyramid

- Wang VH, Foster V, Yi SS. Are recommended dietary patterns equitable? Public Health Nutr. 2022;25(2):464–470. doi:10.1017/S1368980021004158

- Ramírez AS, Golash-Boza T, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Questioning the dietary acculturation paradox: a mixed-methods study of the relationship between food and ethnic identity in a group of Mexican-American women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(3):431–439. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2017.10.008

- Lopez I. Culture and Mediterranean diet. Int J Nutr. 2019; 3(2):13–21. doi:10.14302/issn.2379-7835.ijn-18-2272

- Alexis A. Healthy eating includes cultural foods. Healthline. July 7, 2021. Accessed June 29, 2023. https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/healthy-eating-cultural-foods

- Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt M, Gregory CA, Singh A. Household food security in the United States in 2018. ERR-270. Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. 2019. Accessed July 23, 2023. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/94849/err-270.pdf?v=7154.9.4.

- Kern DM, Auchnicloss AH, Stehr MF, et al. Neighborhood prices of healthier and unhealthier foods and associations with diet quality: evidence from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(11):1394. doi:10.3390/ijerph14111394

- Drewnowski A. Obesity, diets, and social inequalities. Nutr Rev. 2009;67(s1):S36–S393. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00157.x

- Brunner TA, van der Horst K, Siegrist M. Convenience food products. Drivers for consumption. Appetite. 2010;55(3):498–506. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2010.08.017

- Sun Y, Dong D, Ding Y. The impact of dietary knowledge on health: evidence from the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3736. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073736

- Johnson R, Stewart N. Defining low-income, low-access food areas (food deserts). Updated July 6, 2023. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11841

- McGuire S, Nord M, Coleman-Jensen A, Andrews M, Carlson S. Household food security in the United States, 2009. EER-108. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):153–154. doi:10.3945/an.110.000216

- Moreira PA, Padrão PD. Educational and economic determinants of food intake in Portuguese adults: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:58. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-4-58

- What is food insecurity? Feeding America. 2023. Accessed April 4, 2023. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity

- Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW, Parsons R, Ng C, Garriguet D, Tarasuk V. Household food insecurity is a stronger marker of adequacy of nutrient intakes among Canadian compared to American youth and adults. J Nutr. 2015;145(7):1596–1603. doi:10.3945/jn.114.208579

- Morales ME, Berkowitz SA. The relationship between food insecurity, dietary patterns, and obesity. Curr Nutr Rep. 2016;5(1):54–60. doi:10.1007/s13668-016-0153-y

- Food insecurity. Healthy People 2030. 2023. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed July 25, 2023 https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/food-insecurity

- Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–310. doi:10.3945/jn.109.112573

- Wolfson JA, Garcia T, Leung CW. Food insecurity is associated with depression, anxiety, and stress: evidence from the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):64–71. doi:10.1089/heq.2020.0059

- Rutledge K, McDaniel M, Teng S, et al. Food staple. National Geographic. May 19, 2022. Accessed June 10, 2023.https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/food-staple

- Quick facts. Arizona. July 1, 2022. US Census. Accessed July 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/AZ

- Race, diversity, and ethnicity in Arizona City, AZ. Best Neighborhood. 2023. Accessed July 10, 2023. https://bestneighborhood.org/race-in-arizona-city-az

- Community, Research, and Evaluation Development (CRED) Resources. Resources for grant writing, needs assessment and evaluation. The University of Arizona Norton School of Human Ecology. 2023. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://norton.arizona.edu/cred-resources

- Mishev D. A sense of taste: Arizona’s food culture. Visit Arizona. 2023. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://www.visitarizona.com/like-a-local/a-sense-of-taste-arizonas-food-culture

- Lamontagne N. Gene patterns shaping our food choices revealed. Neuro News. 2023. Accessed September 2, 2023. https://neurosciencenews.com/genetics-food-preference-23676/

- Sijangga MO, Pack DV, Yokota NO, Vien MH, Dryland ADG, Ivey SL. Culturally-tailored cookbook for promoting positive dietary change among hypertensive Filipino Americans: a pilot study. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1114919. doi:10.3389/fnut.2023.1114919

- Johnson-Kozlow M, Matt GE, Rock CL, de la Rosa R, Conway TL, Romero RA. Assessment of dietary intakes of Filipino-Americans: implications for food frequency questionnaire design. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2011;43:505–510. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.001

- Li-Geng T, Kilham J, McLeod KM. Cultural Influences on dietary self-management of type 2 diabetes in East Asian Americans: a mixed-methods systematic review. Health Equity. 2020;4(1):31–42. doi:10.1089/heq.2019.0087

- Ghosh S, Meyer-Rochow VB, Jung C. Embracing tradition: the vital role of traditional foods in achieving nutrition security. Foods. 2023;12(23):4220. doi:10.3390/foods12234220

- US Department of Agriculture, US Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition across the lifespan. Customizing the Dietary Guidelines framework. In: Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. 9th ed. US Government Publishing Office; 2020;28-29. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/DGA_2020-2025_CustomizingTheDietaryGuidelines.pdf

- Snetselaar LG, de Jesus JM, DeSilva DM, Stoody EE. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025: understanding the scientific process, guidelines, and key recommendations. Nutr Today. 2021;56(6):287–295. doi:10.1097/NT.0000000000000512

- Vanstone M, Rewegan A, Brundisini F, Giacomini M, Kandasamy S, DeJean D. Diet modification challenges faced by marginalized and nonmarginalized adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Chronic Illn. 2017;13:217–235. doi:10.1177/1742395316675024

- Marsh E. The three sisters of indigenous American agriculture. National Agriculture Library, US Department of Agriculture. 2023. Accessed June 1, 2023 https://www.nal.usda.gov/collections/stories/three-sisters

- Education materials and resources. My Native Plate. Indian Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.ihs.gov/diabetes/education-materials-and-resources/index.cfm?module=productDetails&productID=2468

- Villalona S, Ortiz V, Castillo WJ, Garcia Laumbach S. Cultural relevancy of culinary and nutritional medicine interventions: a scoping review. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2021;16(6):663–671. doi:10.1177/15598276211006342

- Khan S. Cultural humility vs. cultural competence—why providers need both. Healthcity. March 9, 2021. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://healthcity.bmc.org/policy-and-industry/cultural-humility-vs-cultural-competence-providers-need-both

- Center for Medicare Advocacy. Racial and ethnic health care disparities. 2023. Accessed August 7, 2023. https://medicareadvocacy.org/medicare-info/health-care-disparities

- Arizona Department of Health. Arizona Chronic Disease State Strategic Plan. 2012-2017. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.azdhs.gov/prevention/chronic-disease/index.php#about

- Lenhart CM, Wiemken A, Hanlon A, Perkett M, Patterson F. Perceived neighborhood safety related to physical activity but not recreational screen-based sedentary behavior in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):722. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4756-z

- Banner Health, Banner Thunderbird Medical Center. Community Health Needs Assessment. 2019. Accessed June 1, 2023. https://www.bannerhealth.com/-/media/files/project/bh/chna-reports/2019/arizona/banner-thunderbird_-2019-chna-report.ashx

- Arizona. Partnership to Fight Chronic Disease. 2023. Accessed May 14, 2023. https://www.fightchronicdisease.org/states/arizona

- Stats for the state of Arizona. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics. 2017. Accessed July 26, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/states/arizona/arizona.htm

- Yu E, Malik VS, Hu FB. Cardiovascular disease prevention by diet modification: JACC health promotion series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(8):914–926. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.085

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017: estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. Updated May 15, 2024. Accessed November 4, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/php/data-research/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf

- Diabetes. Healthy People 2030. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2023. Accessed July 23, 2023. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/diabetes

- Nam S, Song HJ, Park SY, et al. Challenges of diabetes management in immigrant Korean Americans. Diabetes Educ. 2013;39:213–221. doi:10.1177/0145721713475846

- Pistulka GM, Winch PJ, Park H, et al. Maintaining an outward image: a Korean immigrant’s life with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:825–834. doi:10.1177/1049732312438778

- Chesla CA, Chun KM, Kwan CML. Cultural and family challenges to managing type 2 diabetes in immigrant Chinese Americans. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1812–1816. doi:10.2337/dc09-0278

- Chesla CA, Chun KM. Accommodating type 2 diabetes in the Chinese American family. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:240–255. doi:10.1177/1049732304272050

- Abe M, Fujii H, Funakoshi S, et al. Comparison of body mass index and waist circumference in the prediction of diabetes: a retrospective longitudinal study. Diabetes Ther. 2021;12(10):2663–2676. doi:10.1007/s13300-021-01138-3

- Ochs E, Shohet M. The cultural structuring of mealtime socialization. New Dir Child Adolesc Dev. 2006;(111):35–49. doi:10.1002/cd.154

- Al Bochi R. I’m a dietitian with Syrian roots—this is the Mediterranean Diet that I know and love. EatingWell. July 18, 2023. Accessed July 25, 2023. https://www.eatingwell.com/longform/8059162/dietitian-syrian-roots-mediterranean-diet

- Ayala GX, Pickrel JL, Baquero B, et al. The El Valor de Nuestra Salud clustered randomized controlled trial store-based intervention to promote fruit and vegetable purchasing and consumption. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2022;19(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12966-021-01220-w

- Medina FX. Looking for commensality: on culture, health, heritage, and the Mediterranean diet. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2605. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052605

- Cartwright MM. The prepare-engage-respond model to develop cultural competency in the practice of dietetics. [Manuscript submitted for publication]; J Am Acad Nutr Diet.

Foods that represent the traditions, beliefs, geographic region, ethnic group, religious body, or cross-cultural community. Source: Healthline

A disease and/or a medical or health condition that can be influenced by nutrition and diet.

When individuals adopt eating patterns of a host country. Source: Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

Lipids that are liquid at room temperature. Source: Nutrition Concepts and Controversies, 15th Edition

A round, starchy, usually seedless fruit that resembles bread in color and texture when baked. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Defined as being far from a supermarket, supercenter, or large grocery store. Source: Food Access Research Atlas

Stores or marketplaces where groceries (food, beverages, and common household goods) are sold. Source: Allrecipes

Areas in which high-quality fresh food is challenging to purchase due to lack of proximity to a large grocery store. Source: Congressional Research Service

A food that is regularly consumed, usually in large quantities such that they contribute importantly to the energy needs of a population. Source: Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition, 3rd Edition

a tropical fruit similar to a banana with green skin. Larger in size than bananas, they have a thicker skin. Plantains are also starchier and lower in sugar than bananas. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Refers to the descendants of the native West and Central Africans enslaved and shipped to the Americas via the Atlantic slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries, with large populations in the United States, Brazil, and Haiti.

A dish made of raw fish marinated in lime or lemon juice, often with oil, onions, peppers, and seasonings. Sometimes served as a snack or appetizer. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

The edible fleshy pads of the nopal cactus, used as a staple in Mexican cuisine.

A Chinese cabbage forming an open head with long white stalks and green leaves. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Small pastries filled with sweet or savory ingredients; traditionally associated with Mid-Autumn Festival and moon watching. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

In Chinese cooking, it is a broth or porridge made from rice. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Corn, squash, and beans grown and/or prepared together. Source: US Department of Agriculture's National Agricultural Library

A concentrated food used by North American Indians and consisting of lean meat dried, pounded fine, and mixed with melted fat. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

The skin and fat of whale, cut into small pieces and eaten as food by Intuit people. Source: Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus

Eskimo ice cream made from whipped fat from animals and wild berries. Source: Smithsonian Magazine

A tropical plant also known as screw pine, bearing edible fruit. Source: Britannica

A Hawaiian food prepared from the cooked corms of taro that are mashed with water to the consistency of a paste or thick liquid and often allowed to ferment. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Shredded meat from a pig cooked in an imu (underground oven pit) using traditional Hawaiian methods (covered with plant or banana leaves and steamed). Source: Wikipedia

Meat and fish (e.g., pork, salmon) wrapped in leaves (e.g., taro, ti) and baked or steamed. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

a large round starchy fruit from a tropical evergreen tree, which is used as a vegetable and sometimes to make a substitute for flour. It is widely cultivated on the islands of the Pacific and the Caribbean. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Fish that is steamed and cooked with onions, lime juice, spices, and vegetables, and served on a bed of polenta-like cornmeal; or fried and served with a spicy sauce and flying fish. Source: Taste Atlas

A green leaflike spinach, blended with coconut milk, spices, chilies, sometimes with okra and red meat, then topped with crab.

The edible seeds of various crops (e.g., peas, beans, lentils) of the legume family. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Curried fish gravy made with spices (turmeric, cardamom) served with rice. Source: Wikipedia

Lentil stew with vegetables. Source: Wikipedia

The ability to understand and appreciate cultural beliefs and values of other cultures and to work, communicate, and interact with others of different cultural backgrounds while being aware of one’s own cultural beliefs. Source: National Prevention Information Network

A key learning that can be applied to clinical practice. Source: PubMed

The process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people. Source: Principles of Community Engagement, 2nd Edition

The reddish edible fruit from a tall, treelike cactus that grows in the desert Southwest United States and Mexico. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

The pulpy, pear- or egg-shaped, edible, yellow to purplish-red fruit of a prickly pear cactus. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Someone's understanding of the differences between themselves and people from other countries or other backgrounds, especially differences in attitudes and values. Source: Collins Dictionary

The eating habits and culinary practices of a people, region, or historical period. Source: Michigan State University Cooperative Extension

Developed and published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, this contemporary nutrition guide aligns with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Source: US Department of Agriculture

Cornmeal dough rolled with ground meat or beans seasoned usually with chili, wrapped usually in corn husks, and steamed. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

A small piece of dough enclosing a typically savory filling (e.g., meat, seafood) and cooked usually by boiling, steaming, or pan-frying. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Fats found in animal-based foods such as beef, pork, poultry, full-fat dairy products, eggs, and tropical oils. Because they are typically solid at room temperature, they are sometimes called “solid fats.” Source: American Heart Association

A dynamic and lifelong process focusing on self-reflections and personal critique, acknowledging one’s own biases. Source: University of Oregon Division of Equity and Inclusion

Differences in which disadvantaged social groups such as the poor, racial/ethnic minorities, women, and other groups who have persistently experienced social disadvantage or discrimination systemically experience worse health or greater health risks than more advantaged social groups. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

A chronic condition in which the body does not produce enough insulin or the body resists the effects of insulin, causing elevated blood glucose levels. Source: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

More than 1 medical condition present at the same time in a patient, which often leads to poorer health outcomes. Source: National Library of Medicine

The practice of sharing food and eating together in a social group such as a family.

A model to follow when counseling individuals about dietary modification.