Chapter 3: Enjoying Food at Home and Beyond—Our Relationship with Food

By Ashley Munro, MPH, RDN, CDCES; Katelyn Barker, MS, RDN; Hope Wilson, MPH, RDN, Jennifer Parlin, MPH, Constance Bell, MBA

Student contributors: Diego Quezada, Mia Ochoa, Natalia Rodriguez, Juliette Rico, Nicole Mazon, Sabrina Reynosa

Introduction

Culinary medicine supports individuals in lifelong healthy eating patterns. Effective support must consider the countless ways that individuals interact with food and its meaning in their lives. Food is nourishing beyond the nutrients and energy derived from it. Culinary medicine recognizes and supports the multifaceted relationship people have with food.

Sustaining a healthy eating pattern requires a healthy relationship with food, which honors the social, cultural, and emotional importance of food, along with its nutritional value. Flexibility is key. Empowering people to pursue the various pleasures food brings them can help them sustain health-promoting behaviors more so than restrictive, rigid rules.

To promote lifelong healthy eating patterns, culinary medicine seeks to help people develop cooking skills, and it promotes feasible behavioral changes compatible with a person’s beliefs, preferences, and traditions. From a medical perspective, a fed person is a healthy person, so finding ways to support food choices and patterns that satisfy all aspects of health, including psychosocial health, is key to developing and maintaining a “nourishing” relationship with food.

It is important to remember that weight does not necessarily equate to health, nor does it determine a person’s value or worth. For those with limited resources, obtaining an adequate supply of food and adequate energy and nutrients can be difficult. Dietary recommendations by health professionals must be made with an awareness of the potential limitations to regular access to nutritious foods and the cost. Respect and dignity are central to health promotion and efforts to help a person build a healthy relationship with food.

“Food is everywhere. It penetrates everything—our politics, sociology, anthropology. It’s the way we nurture ourselves, our family, our friends. It’s the way we entertain, the way we socialize. It’s the way we connect with others, the way we explain our culture, celebrate our milestones. And there are always so many more delicious things to eat… Food is a unifier.” — Gail Simmons1

Our Relationship With Food

Health and its pursuit have many layers and are affected by many factors. Food is a good example of a factor with a complex influence on health. Food provides the nutrients essential for growth and function, but its impact is much more than simple biology. Food holds a story that is unique to an individual, and that is rooted in their environments, families, and culture.

A person’s relationship with food and their body starts early and can be disrupted if the personal nature of food and the variety of factors that influence it are not understood and honored. Some foods nourish our bodies; others nourish our souls and create connection. All foods serve a purpose, and what is available to eat and what is eaten help establish adequacy—the basis of any healthy relationship with food.

A healthy relationship between food and the body is flexible, nonjudgmental, and nonrestrictive, and considers lived experiences, culture, and the food environment.2,3 A healthy relationship with food foregoes dichotomous thinking, allows for relaxed eating, decreases pressure by limiting rules relative to food, and embraces body diversity.

A healthy relationship with food promotes sustainable food practices, because of flexibility. It is not enough to promote balanced nutrition habits if those practices are not sustainable. Restrictive and rigid food beliefs and rules are not sustainable over time, and they increase the risk of poor health outcomes and the development of disordered eating.2,4

People are experts on their own bodies; they know how they respond to food and what truly provides satisfaction and pleasure. Empowering individuals to pursue pleasure can go hand in hand with empowering individuals and communities to engage in health-promoting behaviors.5 This is especially true when we encourage rich, diverse, culturally appropriate food options without overly focusing on body size.

Looking at people and communities as experts is vital to building trusting and positive relationships with communities that support their lived experiences. Understanding communities and people’s food stories provides practitioners important insight. This awareness and understanding allow providers to engage in more meaningful and sustainable change talk that is more informed than external and general food and nutrition recommendations.5,6 This understanding and asset-based thinking can help build a collaborative and respectful process of learning how to incorporate nourishing foods into people’s lives. Helping people work with what is available to them, and talking about food from a positive perspective can remind them that we’ve always known how to feed ourselves; we just need to listen to inner cues and honor them.

This chapter explores what affects our relationship with food, the food environment, and how to incorporate pleasure from a place of nonjudgment and reviews the importance of coming together as individuals in communities and families to enjoy a meal, at home and elsewhere.

Complex Factors

Many intersecting factors influence a person’s relationship with food.2 These factors include external and internal influences, such as messages about food hierarchy from family, doctors, and teachers, and other factors, such as genetics, traumatic experiences, and food access.2,4 The idea that an individual is in full control of these factors is misguided. This desire to control food can be the source of blame and shame regarding the choices people make regarding food and general care for their body.

The environment and social norms that are created around food influence how people relate and interact with food. Social norms are often based on what people believe to be normal, typical, or appropriate. Social norms can function as unspoken rules or guidelines for how people behave and are expected to behave. People generally follow social norms because they want to fit in with the people around them.5

Social norm factors that influence food choices include:

- Diet culture

- “Good” vs “bad” food messages

- Social media displaying the “right way to eat”

- Societal or family food beliefs/attitudes

- Westernized foods being labeled “healthy” while cultural foods are demonized5

Diet culture encourages dieting behaviors associated with long-term health consequences, such as muscle loss from repeated weight loss attempts, weakened bones, high blood pressure, and chronic inflammation. Dieting also increases the risk of poor body image and is a strong contributor to eating disorders.2

Diet culture is all around because the drive for weight loss and “health” or “wellness” is adjacent to morality and social status.5,6 This affects the relationship with food because it causes a disruption in being able to listen to the body’s needs, and it can cause internal judgment of food choices if they do not align with what is viewed as healthy or nutritious.

When food is not accessible and when life is stressful due to environmental factors (e.g., unstable housing, unsafe spaces, financial insecurity, historical trauma, systemic racism), it’s challenging to have a peaceful relationship with food. An example of this would be wanting to eat something because you feel hungry, but the food available is convenience food or only foods that diet culture has deemed “unhealthy,” so you skip the meal in fear of weight gain and further stigma, which keeps you in a negative cycle with your relationship with food.7,8

This can be further complicated if a person then eats when they are hungry but outside the rules that diet culture has dictated. The person then may feel guilt and shame for those choices; thanks to confirmation bias, this then erodes trust within the body. This phenomenon keeps people in the cycle of not trusting their bodies when it comes to food. They believe a food is bad for them, which creates a power struggle with this food, and when they do eat it, they may end up feeling they have to eat a lot because it is an “off–limits” food. Thus, confirming that this food is not safe or “good.”

Interpersonal relationships affect how we view food and bodies. Each individual has lived experiences that shape how they relate to food. Food plays a vital role in many communities and cultures; the importance is meaningful and diverse. Authors Hilary Kinavey and Dana Sturtevant noted in Reclaiming Body Trust: A Path to Healing and Liberation that “Eating is not—and should never be—just about survival. For human beings, food is flavored with complex meanings. It tells the story of your ancestors, your culture, and your history. The bottom line: When people mess with your food, they are messing with your life in ways rarely anticipated or understood.”5

Another area that affects an individual’s relationship with food and that often overlaps with relationships and the environment is a person’s attitudes and beliefs about food. These beliefs are often learned and may come from others (e.g., doctors, family members, dietitians), the media, or through one’s own lived experiences with food (see the “Measuring Beliefs About Food and Nutrition” text box).2,6

Measuring Beliefs About Food and Nutrition

A variety of food beliefs can be measured by asking questions such as:

- Do you get nervous eating certain foods out of fear they are “bad” for you (e.g., gluten, sugar)?

- Do you label food as good, bad, healthy, or unhealthy?

- Do you label your cultural foods (or others’) as unhealthy?

- Do you have rules about food that feel stressful (e.g., don’t eat after 7 PM, you should avoid carbohydrates, you should avoid beans, sweets are bad)?

- Do you believe willpower and personal choice are important to achieve health?

The questions in the preceding text box relate to some examples of food beliefs. Often, these kinds of beliefs can lead to a more negative relationship with food if not explored or challenged. Challenging these ideas can be helpful. It can also be interesting to consider whether these statements are true—or true for that person. Answers to these kinds of questions provide more to the person’s “story” and can be a very helpful starting point when working with people and supporting them in behavior change.

Ultimately, health is not a moral obligation, and there is no virtue in food choices. Tanya Denise Fields, a food justice activist, once noted, “People don’t make good food choices, they have them.”9 This underpins the complex role that society and the social determinants of health play in shaping a person’s relationship with food, and thus can deeply affect overall health outcomes.10

In the following interactive activity, select the > to read additional information:

Health is also multifaceted and individual. Overall health encompasses many other behaviors and factors, such as sleep, tobacco use, access to quality medical care, access to medical care, alcohol use, genetics, stress, family history, social support (or lack thereof), access to safe spaces, access to transportation, and so much more. These are all determinants of health and make up 30% to 55% of what affects a person’s health.11

The lack of access to equitable and unbiased health care can hold individuals back from achieving what is deemed good health for them. Avoidance of health care is not always considered and can be a useful place to start rather than assuming a person “just” needs to eat better to be healthier. “Food, though a physiological necessity and required for good health and functionality, also contributes to the social, cultural, psychological and emotional well-being of our lives.”8

Food Environment and the Pleasure Factor

Our relationship with food includes our experience with the community we engage with while eating it. Many cultures and communities find belonging and connection through food. Food is associated with emotion in humans, and that is an important part to consider when discussing food and nutrition with individuals.5,7 The idea of experiencing food through community intersects with social support and how that affects overall health. A survey at the University of Arizona in 2021 found that 45.4% of students surveyed (n = 5,253) indicated that comparing their food or body on social media had a negative impact on their mental well-being.12 This illustrates that while community is important, social media can have a harmful impact on body image and food beliefs given the lack of regulation of information about nutrition and health.

There are many ways to eat a meal, and there are often hidden rules about the “correct” way to eat. Examples include that meals must be mindful or undistracted, or must be eaten with a fork or a spoon. These are examples of Westernized beliefs. Westernization6 reached much of the world as part of the process of colonialism and continues to be a significant cultural phenomenon, due to globalization of ideas about food and meals that can influence how individuals engage with food. Ableism in mealtime behaviors is well known. This can be especially true when learning or supporting those feeding children or neurodivergent individuals. If allowed, diet culture and Westernized beliefs can challenge the potential enjoyment of eating a meal.6

There is no 1 correct way to eat; it is more about asking how and with whom individuals eat in a way that brings them the most safety and ease. In some cultures, eating with one’s hands or having music on is typical, or a child may need the support of a device to nourish themselves. Eating is an opportunity to enjoy, nourish, and experience pleasure, and that may look different for different cultures and individuals. The idea of maintaining pleasure with respect to eating is fascinating. adrienne maree brown once said, “What if it’s a measure of our freedom to reclaim pleasure?”13

Pleasure is a word that is often viewed as something to feel shame about. Centering pleasure and satisfaction when we consider eating can be rewarding and unlock more attuned forms of eating and movement. Many things can bring someone back to finding pleasure in food.5

Cooking Can Influence Our Pleasure Factor

Preparing meals that matter to a person can make a difference. This can mean meals that support connection with one’s ancestors, connection with one’s community, or just connection with the people one engages with. Food preparation is a very positive sensory experience for some, which can empower them to try new things and play with food.

Asking individuals if they like to cook or what experience they have with cooking is a doorway to learning if they find importance in this act. These questions can lead to conversations about new recipes to try or other behavior strategies that will increase variety in a person’s meal pattern. By reconnecting with food from childhood or an individual’s culture, there can be permission for pleasure, especially if diet culture or health messages they’ve received about their cultural foods have been negative or have a lot of bias. Cooking can also create self-efficacy, which makes behavior change more sustainable and enjoyable.14

Environment Can Affect Pleasure

Eating outside or alone or with others, learning what environment supports having a relaxed experience with food, and having pleasure with food can be helpful. Learning about the environment and an individual’s relationship with pleasure can be discussed more broadly by exploring values.3,5,6

Our values are what we as individuals view as important tenets of our lives. Understanding what is important to us allows us to consider if our beliefs and behaviors align with those values.15 For example, if a person values connection but eats in isolation, the food behavior is not in alignment with their value and need to support self-care.

All the Reasons We Eat

Food is universal. Food is needed for our survival, so it is natural that food plays a major role in individuals’ lives. Much like a person’s relationship with their body, their relationship with food intersects with their body and with how they might express themselves, share experiences, and cope with emotions.

Emotional eating is normal and an important part of the human experience.16,17 The only reason emotional eating is often demonized is due to the fear of and biases toward having a higher weight. Body diversity is natural and there are many reasons people eat and support the body they inhabit. It is not uncommon for food restriction to be recommended to decrease emotional eating, but this can cause unintentional harm.

Food restrictions and recommendations to limit foods can harm a person’s relationship with food and can also lead to disordered eating.2,18,19 Disordered eating and diagnosed eating disorders fall along a spectrum. Disordered eating involves the same behaviors as a clinically diagnosed eating disorder, but the frequency and severity of the disordered habits differ.

“Normal” eating, as defined by Ellyn Satter,17 is flexible and free from shame and guilt; thus, when eating becomes inflexible or causes feelings of shame and guilt, this can be a sign of an unhealthy relationship with food. Here are some examples of disordered eating habits:

- Avoiding entire food groups, certain macronutrients, or foods with specific textures or colors without a medical reason

- Binge eating (i.e., eating larger-than-typical amounts of food), which often can result from restriction and end with backlash of shame and/or frustration

- Engaging in compensatory behaviors, such as exercising to “make up for” or “earn” food

- Engaging in purging behaviors, such as using laxatives, avoiding insulin doses (i.e., diabulimia, which is specific to people with diabetes), overexercising, or vomiting to control weight

- Exercising compulsively and having increased stress about limiting activity

- Feeling guilt, disgust, or anxiety before or after eating

- Feeling preoccupied by food

- Following strict food rules or rituals

- Intentionally skipping meals (including skipping meals before or after consuming a large meal) or restricting food intake or food or alcohol a person considers unhealthy

- Weighing or taking body measurements often

Even when disordered eating doesn’t lead to a clinical eating disorder, it is associated with poorer mental and physical health.20,21 Many people do not meet the diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder but struggle with painfully disordered thoughts about behaviors related to food.

There are also many people who do meet the clinical criteria for an eating disorder but aren’t diagnosed, because of various forms of bias and treatment disparities. An example is patients with higher weight who meet all the behavioral criteria for an eating disorder but aren’t diagnosed because they aren’t “small enough” or don’t “look like” they have an eating disorder.18,19,21 Disordered eating behaviors aren’t always obvious, and many health-care providers don’t have the tools needed to identify them. The “Eating Disorder Screening Questions” text box provides some questions that health-care providers can use to screen for disordered eating.

Eating Disorder Screening Questions

for Health-Care Professionals

- Would you say that food dominates your life?

- Do you ever feel out of control around food, like you cannot stop eating until you are uncomfortably full?

- Do you ever eat in secret? Or do you feel guilt or shame about eating?

- Does your weight affect the way you feel about yourself?

- Is the list of foods you like and will eat shorter than a list of foods you won’t eat?

- Do you ever make yourself throw up, use laxatives or diuretics, or overexercise to control your weight?

- Do you experience any barriers in accessing food (e.g., scarcity, others intervening in your choices, lack of transportation)

- Do you ever skip your insulin (diabetes specific) or other medications to control your weight?

Emotions and Food Are Part of the Human Experience

People may use food when they experience emotions, including happiness, sadness, and stress, among others, and food is often an option for self-care. Celebrating with foods can be joyful (e.g., celebrating a holiday or special achievement). Food can also be a support drawn upon when people are homesick or in need of comfort (e.g., making a traditional meal from your region, culture, or home country while living abroad).

Food may serve as a coping skill for some people, or it could be their only accessible coping skill. Regardless, food is very personal, and it is not recommended to insert judgment about how or why a person is eating; rather, it can be an opportunity to engage with people, seek understanding, and maintain curiosity.16

Activity

Food Memory Reflections

- Consider a memory you have about food.

- What food or dish was made, what was the occasion?

- Where were you and how old were you?

- Who made the dish?

- What did you feel and how do you connect with this memory now, if at all?

Maintaining a Healthy Relationship With Food

In this chapter, we have presented examples of why our relationship with food is so complex and how that relates to how we each may view our body. We also discussed food as a way to connect with others, express culture, and find pleasure.

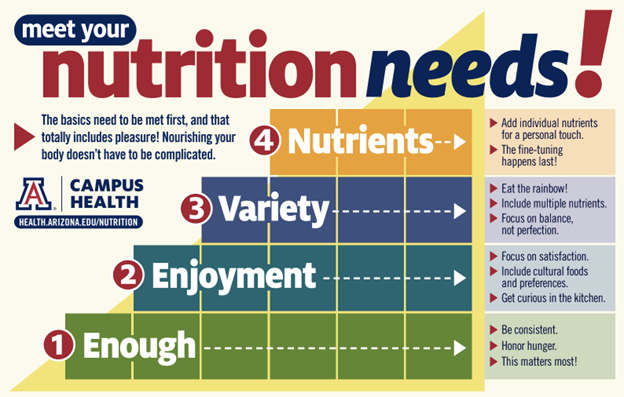

There are many reasons a person’s relationship with food might be altered. Diet culture is a barrier, as are systemic and environmental factors that interfere with peaceful relationships with food.22 From a medical perspective, a fed person is a healthy person, so finding ways to support adequacy is key to having and maintaining any food relationship. It is only after adequacy and sustainability are addressed that we can think about nutritional balance. Balance means nothing if it is not sustainable.

Lastly, food and bodies are tied, so often it can be important to remember that weight does not equate to health or determine a person’s value or worth. Respect and dignity are at the center of health promotion and relating to food.

Key Takeaways

- Adequacy and flexibility are at the center of a healthy relationship with food. People need enough food first before they can think about how their relationship with food can improve or heal.

- If food is stressful, it is no longer health promoting. Health is multifaceted and requires many systems working together to be successful.

- Health doesn’t “look” a certain way; often, having a peaceful relationship with food can lead to positive health outcomes.

- Food is more than just nutrients. Food is how we connect to our heritage, family, and friends. We can find pleasure in food; there is nothing wrong with wanting to enjoy the experience with food.

Suggested/Additional Reading Lists

- Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body Liberation by Dalia Kinsey, RD, LD (BenBella Books, Inc.; 2022)

- It’s Always Been Ours: Rewriting the Story of Black Women’s Bodies by Jessica Wilson, MS, RD (Hatchett Book Group)

- Resch E. Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Anti-Diet Approach. 4th ed. by Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch (St Martin’s Press; 2020)

- Anti-Diet: Reclaim Your Time, Money, Well-Being, and Happiness Through Intuitive Eating by Christy Harrison, MPH, RD (Little Brown Spark; 2019)

References

- Gardner L. Why We Cook: Women on Food, Identity, and Connection. Workman Publishing; 2021.

- Tribole E, Resch E. Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Anti-Diet Approach. 4th ed. St Martin’s Press; 2020.

- Kinsey D. Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body Liberation. BenBella Books, Inc.; 2022.

- Patton GC, Selzer R, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Wolfe R. Onset of adolescent eating disorders: population based cohort study over 3 years. BMJ. 1999;318(7186):765. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7186.765

- Kinavey H, Sturtevant D. Reclaiming Body Trust: A Path to Healing & Liberation. TarcherPerigee; 2022.

- Nemec K. Cultural awareness of eating patterns in the health care setting. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2020;16(5):204–207. doi:10.1002/cld.1019

- Hazzard VM, Loth KA, Hooper L, Becker CB. Food insecurity and eating disorders: a review of emerging evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(12):74. doi:10.1007/s11920-020-01200-0

- Kinavey H, Cool C. The broken lens: how anti-fat bias in psychotherapy is harming our clients and what to do about it. Women Ther. 2019;42(1–2):116–130. doi:10.1080/02703149.2018.1524070

- Fields TD. Exploring the intersections of human trafficking, mental health, eating disorders, food justice and weight stigma, presented at: Amplify and Unite Health and Wellness Summit; June 4, 2021.

- Healthy People 2030. Social determinants of health. US Department of Health and Human Services. Accessed October 27, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health#:~:text=Social%20determinants%20of%20health%20(SDOH,Education%20Access%20and%20Quality.

- Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. Accessed October 27, 2024. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1.

- University of Arizona Campus Health Service. 2022 Health and wellness survey aggregate report for public use – weighted undergraduate report. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://health.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/2023-03/2022%20aggregate%20undergrads%20final%20PUBLIC.pdf

- brown am. Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good. AK Press; 2019.

- Lo BK, Loui C, Folta SC, et al. Self-efficacy and cooking confidence are associated with fruit and vegetable intake in a cross-sectional study with rural women. Eat Behav. 2019;33:34–39. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.02.005

- Dare to lead list of values. Brené Brown. July 5, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2024. https://brenebrown.com/resources/dare-to-lead-list-of-values/

- Byrne C. I’m a dietitian and it’s time to stop pathologizing ‘emotional eating.’ SELF. August 5, 2022. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.self.com/story/emotional-eating-normal

- What is normal eating? Ellyn Satter Institute; 2018. Accessed October 27, 2024. https://www.ellynsatterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/What-is-normal-eating-Secure.pdf.

- Thorne R. Everything you need to know about disordered eating, according to experts. Healthline. September 14, 2022. Accessed November 25, 2024. https://www.healthline.com/health/disordered-eating-vs-eating-disorder#risk-factors-and-demographics

- Nurkkala M, Keränen AM, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, et al. Disordered eating behavior, health and motives to exercise in young men: cross-sectional population-based MOPO study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:483. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-3162-2

- Darling KE, Fahrenkamp AJ, Wilson SM, D’Auria AL, Sato AF. Physical and mental health outcomes associated with prior food insecurity among young adults. J Health Psychol. 2015;22(5):572–581. doi:10.1177/1359105315609087

- Babbott KM, Cavadino A, Brenton-Peters J, Consedine NS, Roberts M. Outcomes of intuitive eating interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Disord. 2022;31(1):33–63. doi:10.1080/10640266.2022.2030124

- Harrison, C. Anti-Diet: Reclaim Your Time, Money, Well-Being, and Happiness Through Intuitive Eating. Little Brown Spark; 2019.

The physical, social, economic, cultural, and political factors that impact the accessibility, availability, and adequacy of food within a community or region. Source: Intuitive Eating: A Revolutionary Anti-Diet Approach, 4th Edition

The tendency to think in terms of polar opposites—that is, in terms of the best and worst. Also referred to as "black-and-white thinking” or “all-or-none thinking." Sources: APA Dictionary of Psychology and Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences

Sensitivity to other cultures; refers to the awareness of how other ethnic, racial, and/or linguistic groups differ from one’s own. Source: Encyclopedia.com

The perceived informal, mostly unwritten, rules that define acceptable and appropriate actions within a given group or community, thus guiding human behavior. Source: UNICEF

Often describes a set of societal beliefs pertaining to food and body image, primarily focused on losing weight, an endorsement of thinness as a high moral standard, and the alteration of food consumption. Source: Wikipedia

Foods that represent the traditions, beliefs, geographic region, ethnic group, religious body, or cross-cultural community. Source: Healthline

Multigenerational trauma experienced by a specific cultural, racial, or ethnic group. Source: Administration for Children & Families

Policies and practices that exist throughout a whole society or organization and that result in and support a continued unfair advantage to some people and unfair or harmful treatment of others based on race. Source: Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus

The tendency to gather evidence that confirms preexisting expectations, typically by emphasizing or pursuing supporting evidence while dismissing or failing to seek contradictory evidence. Source: American Psychological Association Dictionary of Psychology

A social association, connection, or affiliation between 2 or more people. Source: Wikipedia

The adoption of the practices and culture of Western Europe by societies and countries in other parts of the world, whether through compulsion or influence. Source: Britannica

Domination of a people or area by a foreign state or nation : the practice of extending and maintaining a nation's political and economic control over another people or area. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Discrimination or prejudice against individuals with disabilities. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Refers to people whose ways of thinking, learning, and behaving fall outside of what is considered "neurotypical" or “normal.”

Eating in response to any human emotion, negative or positive. Also known as "stress eating." Source: Wikipedia

Unfairly supporting or opposing a particular person or thing because of allowing personal opinions to influence your judgment. Source: Cambridge Dictionary

Food and diet-related behaviors that don’t meet diagnostic criteria for recognized eating disorders but still negatively affect someone’s physical, mental, or emotional health. Source: PubMed

Any of several psychological disorders (e.g., anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, bulimia) characterized by serious disturbances of eating behavior. Source: PubMed

A method a person uses to deal with a stressful situation. It may help a person face a situation, take action, and be flexible and persistent in solving problems. Source: National Cancer Institute