AI Literacy

Kainan Jarrette and Diana Daly

What AI Is and Isn’t

“Artificial Intelligence” and “AI” are terms that have begun to dominate our cultural conversations. AI is being integrated into a wide variety of industries, there are countless books and other media on the topic, and everyone seems to have an opinion about it. It’s popular to love it, it’s popular to hate it, and yet most of us can’t identify everywhere it shows up in our daily lives.

So let’s start out by giving a useful definition. Artificial Intelligence (or AI) refers to computer systems that are built to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence. At the time of this writing, most AI systems being used are referred to as narrow AI – smaller systems designed to perform a very limited and specific set of tasks. General AI is the idea of actually replicating flexible, adaptive human intelligence in a single system — something that hasn’t been achieved yet.

So let’s start out by giving a useful definition. Artificial Intelligence (or AI) refers to computer systems that are built to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence. At the time of this writing, most AI systems being used are referred to as narrow AI – smaller systems designed to perform a very limited and specific set of tasks. General AI is the idea of actually replicating flexible, adaptive human intelligence in a single system — something that hasn’t been achieved yet.

You might also have heard the term Large Language Model (or LLM). A Large Language Model is essentially just an AI that has been trained on a vast amount of data so that what it generates (including text) is much more complex. These are AI such as ChatGPT, Gemini, or LLaMA. Whereas AI like what’s used to predict text when you’re typing on your phone would be considered a “small language” model.

Before we go further, let’s clear up three common myths about AI:

AI Myths

Myth 01: AI is Conscious.

It’s not. AI replicates patterns, not inner-experience. Which isn’t to dismiss that the concept of AI raises some incredibly interesting philosophical questions. But it is to say that, at least for now, nobody has to worry about “sentient AI.”

Myth 02: AI is Objective and Infallible.

It’s not. As we’ll discuss more below, AI absorbs all the biases and flaws of the data it’s trained on and prioritizes giving any answer over giving a correct answer.

Myth 03: AI is monolithic.

It’s not. AI is often talked about as though it’s one central force or system, but in reality it’s a broad concept used in tons of different and unique systems. This also means that not all AI provides the same benefits, has the same flaws, or poses the same risks.

Skepticism vs Panic

There are a lot of misconceptions and misinformation about AI, but we also want to acknowledge that the application and integration of AI raises some very serious and valid concerns. It’s healthy to be skeptical of how AI is used.

There are a lot of misconceptions and misinformation about AI, but we also want to acknowledge that the application and integration of AI raises some very serious and valid concerns. It’s healthy to be skeptical of how AI is used.

The issue arises when that skepticism turns to panic and fear. Fearing a technology makes us want to disengage with it, and we need skeptics to be engaging. Otherwise, only the blindly optimistic are left to guide where this technology goes, and that usually doesn’t end up well.

AI and Misinformation

The concepts and tenants of critical thinking have been around long before AI was even a dream. However, AI has come to influence media and information culture so much that covering certain AI topics is unavoidable when talking about misinformation.

Here are some basic concepts to keep in mind when it comes to how AI fuels misinformation:

Hallucinations

In particular, LLMs such as ChatGPT or Google Gemini are:

- Designed to predict patterns, not create a repository of truth

- Generate text based on what sounds right, not what is right

- Designed to “fill in the blanks” rather than say they don’t know

Importantly, not only will AI fabricate inaccurate information, but it will do so confidently and (often) convincingly. So much so that AI hallucinations have sometimes even made their way into mainstream publications1.

Biases and Flaws

LLMs are designed to learn from very large datasets created by extracting (also called scraping) all sorts of media from across the internet. However, this also means that these AI models are absorbing whatever biases and flaws are inherent in that data. This means it can end up replicating prejudices2, stereotypes3, or cultural bias4.

Ideally these datasets are curated by humans to remove or mitigate those flaws, but unfortunately that’s not something we can currently count on.

Manipulative Media

It’s a big enough issue that AI can create fake and inaccurate text. But recent advancements have seen a huge leap in AI’s ability to create more detailed fake media, such as photos, audio, and video. What’s more, it’s become very difficult to spot that these pieces of media are AI creations. While most people still think they’re good at spotting them, research5 shows otherwise.

You can test your own ability to spot a deepfake by taking this online quiz developed by iProov here.

Erosion of Human Thinking

Simply put, there is a growing body of research6 that seems to indicate that when we let AI do too much of our thinking for us, it actually weakens our own cognitive ability. Our brain is set up to maintain neural networks and connections based on how often they’re used.

Growing up, you may have heard the idea that “your brain is like a muscle.” While biologically this isn’t accurate, and the phrase itself has grown cliche, it is incredibly useful as a metaphor. In the most basic sense, if you don’t exercise your brain, it will grow weaker.

Tips for Using AI Wisely

Given the above ways that AI can fuel misinformation, there are two main tips that can help you use AI while still protecting yourself against misinformation and manipulation:

01. Always Verify Facts and Citations AI Provides

It’s not a great idea to ever assume that AI is giving you accurate information. AI provided information should always be verified in ways like:

It’s not a great idea to ever assume that AI is giving you accurate information. AI provided information should always be verified in ways like:

- If AI makes a claim, ask it directly to cite the sources it’s using for that claim.

- When AI provides sources or citations, verify that they actually exist.

- Make sure you can find the sources and citations outside of the AI tool you’re using.

- If sources and citations are real, check for bias and reliability as you would any source

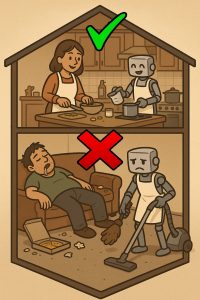

02. Treat AI as a Collaborative Tool, Not a Substitute for Your Own Reasoning

If you find that AI is doing a majority of the work, you’re probably using it wrong. This means:

If you find that AI is doing a majority of the work, you’re probably using it wrong. This means:

- Use AI as a brainstorming tool

- For example, rather than asking AI to write an entire essay for you, instead ask it to help you brainstorm things like topic ideas, structure, key points, etc.

- If using generative AI, leave some creativity for yourself

- A nice use of generative AI is providing simple image-based media for people who may not have any real illustration ability. However, this doesn’t mean you need to let AI do everything. If, for instance, you want to make an image, don’t just prompt the AI to “make a comic about red herrings.” Think about what you want that image to be and try to describe it in as much detail as possible in your prompt. Not only does this usually end up being faster, but it allows you to still work cognitive and creative muscles.

- Avoid using AI for final drafts of text-based media

- There may be cases where you feel it’s appropriate to have AI write an entire first draft of something for you. But even then, you should always be revising what it gave you to make sure it’s in your own voice.

An Example of how AI and Misinformation Interact

The Sheldon Quote

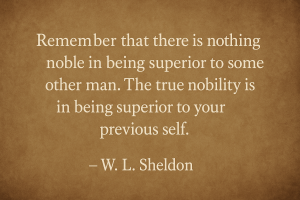

In the introduction chapter of this section, you saw a quote:

It’s likely you’ve seen some version of that quote before, but it’s significantly less likely that you’ve seen it attributed to W.L. Sheldon. That’s because the quote is most often attributed, at least online, to Ernest Hemingway. In fact, if you Google the first line of the quote exactly, the first and most prominent results will tell you it’s a Hemingway quote. It’s in the AI Overview, it’s listed as a Hemingway quote on Goodreads, on Reddit, and so on.

The problem is that Ernest Hemingway never said or wrote this.

We found this out when trying to verify the attribution (this is, after all, a book on misinformation, and inaccurately attributing a quote because we didn’t do our due diligence would be slightly embarrassing). There’s not a single source anyone can point to that verifies this was ever even a quote Hemingway adapted. He simply never said it.

But if you ask AI (including any of the LLMs) to identify the quote, it will confidently tell you some form of “this quote is widely attributed to Ernest Hemingway.” And it does this because that’s who the majority of internet sources attribute it to. When you ask it to cite where exactly Hemingway said this, however, it will just as quickly admit that there’s no evidence Hemingway ever said or wrote it.

Here’s where things get even stickier. If you then ask AI to tell you where the quote did originate, it will… make something up. ChatGPT got close by attributing it to the wrong Sheldon, in a text that doesn’t exist. Gemini attributed it to a current middle-aged author, implying the quote didn’t exist before then. And so on.

Eventually, through our own research and digging, we were able to verify that:

- This quote does indeed appear7 in “What to Believe: An Ethical Creed,” by W.L. Sheldon in 1897

- Sheldon was an American lecturer and ethicist who founded the Ethical Society of St. Louis, which claimed to focus on building community around shared ethical endeavor, rather than shared religion, philosophy, etc. (although it should be noted that Sheldon was highly religious).

- While the idea of the quote likely pre-dates the Sheldon publication, the Sheldon publication is most likely the first time the quote appeared in print

How Misinformation Spreads and Is Reinforced

To begin with, this anecdote is a nice reminder that a lot of quotes floating around the internet are misattributed — keep that in mind the next time you’re about to share one.

While a misattributed quote is generally one of the least harmful types of misinformation, it highlights one of the processes by which misinformation becomes culturally embedded:

- At some point, someone actively decided to misattribute the quote to Hemingway

- Evidence suggests that Playboy magazine was the culprit8, as early at the 1960s

- The general public doesn’t question the attribution to Hemingway, likely because:

- Very few people know who W.L. Sheldon was

- Playboy was considered a reputable and influential publication at the time

- It sounds like something Hemingway would have said

- Once the internet became popularized in the 90s, the quote had enjoyed three decades of false attribution without question. What started as misinformation in print media becomes misinformation in digital media.

- The falsely attributed quote is then shared to exponentially larger degrees than before, particularly with the rise of social media and the increasing “memefication” of culture.

- The falsely attributed quote becomes so digitally embedded that even AI (incorrectly viewed by many as infallible repositories of knowledge) declares the quote to be from Hemingway, embedding the misinformation even further into both local and global culture

In many ways, this is similar to the Illusory Truth Effect we talked about in an earlier chapter.

This gives you an idea of how easy it is for misinformation to spread, even without malicious intent. It also shows how important it is to question the information AI is giving you.

Who Said That?

Try this as a quick exercise:

Think of a quote you love, but that you’ve never verified. Who do you currently think quote is attributed to?

Now, go try to find research where the quote actually originated.

- What do the top Google results say?

- What does AI say?

- Can you find and verify a source of origin? If so, did it match with who you originally attributed the quote to?

Vocabulary

artificial intelligence

computer systems that are built to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence

replicating flexible, adaptive human intelligence in a single AI system

Large Language Model

a type of AI that has been trained on a vast amount of data so that what it generates is much more complex

narrow AI

smaller AI systems designed to perform a very limited and specific set of tasks

scraping

the process by which AI extracts large amount of data from online sources

References

1 Blair, E. (2025, May 20). How an AI‑generated summer reading list got published in major newspapers. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2025/05/20/nx-s1-5405022/fake-summer-reading-list-ai

2 Jindal, A. (2022). Misguided Artificial Intelligence: How racial bias is built into clinical models. Brown Hospital Medicine, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.56305/001c.38021

3 Hofmann, V., Kalluri, P. R., Jurafsky, D., & King, S. (2024, August 28). AI generates covertly racist decisions about people based on their dialect. Nature, 633(8028), 147–154. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07856-5

4 Tao, Y., Viberg, O., Baker, R. S., & Kizilcec, R. F. (2024). Cultural bias and cultural alignment of large language models. PNAS Nexus, 3(9), 346. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae346

5 Köbis, N. C., Doležalová, B., & Soraperra, I. (2021). Fooled twice: People cannot detect deepfakes but think they can. iScience, 24(11), Article 103364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2021.103364

6 Lee, H.‑P. (Hank), Sarkar, A., Tankelevitch, L., Drosos, I., Rintel, S., Banks, R., & Wilson, N. (2025, April). The impact of generative AI on critical thinking: Self‑reported reductions in cognitive effort and confidence effects from a survey of knowledge workers. In Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’25) (Article 1121, pp. 1–22). Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713778

7 Sheldon, W. L. (1897). What to believe: An ethical creed. In Ethical addresses (pp. 57–76). The Commercial Printing Company. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Ethical_Addresses/PkYxAQAAMAAJ?gbpv=1&kptab=overview

8 MacZura, G. (2021, January 5). Hemingway didn’t say that. The Hemingway Society. https://www.hemingwaysociety.org/hemingway-didnt-say

Media Attributions

- AI Brain © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- AI Tall Tale © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- AI Panic © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- AI Makes Things Up © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- AI Absorbs Everything (w period)

- AI Fake Media © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- AI Weakens Our Skills © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- AI Claims © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- AI Good and Bad © ChatGPT adapted by Kainan Jarrette is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- WL Sheldon Quote © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Hemingway Sketch w Words © ChatGPT adapted by Kainan Jarrette is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

computer systems that are built to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence

smaller AI systems designed to perform a very limited and specific set of tasks

replicating flexible, adaptive human intelligence in a single AI system

a type of AI that has been trained on a vast amount of data so that what it generates is much more complex

the practice of carefully analyzing information, beliefs, and arguments in order to make well-reasoned decisions, form justified beliefs, and avoid being misled

false, inaccurate, or misleading information

the process by which AI extracts large amount of data from online sources

the tendency to believe something is true simply because we've had repeated exposure to it