Epistemology

Kainan Jarrette and Diana Daly

What is Epistemology?

Start Here!

Simply put, epistemology is the study of how we know what we know. On a deeper level, epistemology looks to help identify the difference between a belief and knowledge.

Belief vs Opinion

In the context of this book, the term “belief” is not interchangeable with the term “opinion.” An opinion is a feeling about something subjective. This could be your feelings about a movie or your feelings about if something is moral. The important point is that these things aren’t falsifiable — no amount of investigation of the world can tell you if an opinion is factually right or wrong, because those terms simply don’t apply. For instance, if I think strawberries taste bad and you think they taste good, neither of us is factually wrong (unless one of us was knowingly lying about our preference).

In contrast, a belief relates to something objective. These are statements or ideas that are falsifiable, meaning you can investigate the world to help identify how true or false they are. For instance, if I think strawberries grow on trees and you think strawberries grow on vines from the ground, one of us is factually wrong (it’s me!). We can figure out who’s wrong by simply investigating how strawberries grow in the world, and consistently seeing that they grow on vines from the ground and never on trees.

The easiest way to begin to identify if something is a belief or knowledge is to ask:

Let’s say you ask someone if crime is getting better or worse in their city, and they answer “I believe it’s getting better.” You then ask that person why they believe that.

A belief response would sound like: “Because just look around, you can see it’s getting better.”

A knowledge response would sound like: “Because the most recent crime statistics released by local law enforcement agencies shows there has been a drop in the rate of most crime over the past year.”

Which of the two responses sounds most convincing to you?

Reality, Evidence, and Reasoning

On its own, belief is something a person holds to be true without necessarily having rational justification for it. Knowledge, in contrast, is a justified belief. By “justified” we mean that the belief has the following traits:

01. It corresponds with reality.

In other words, the belief accurately reflects or represents the way things actually are.

An obvious example would be: if you believe it’s raining outside, but it’s actually bright and sunny out, your belief does not correspond with reality.

But this can also take more pernicious forms, such as holding a belief that the Earth is flat or that the moon landing was a hoax. It’s not simply that these things are controversial, it’s that they’re demonstrably false — if you travel 35,000 feet above the Earth’s surface, you’ll see the curvature; there are thousands of photos, videos, testimonials, and living astronauts of the time who can attest to the reality of the moon landing. Which leads nicely into the next trait…

But this can also take more pernicious forms, such as holding a belief that the Earth is flat or that the moon landing was a hoax. It’s not simply that these things are controversial, it’s that they’re demonstrably false — if you travel 35,000 feet above the Earth’s surface, you’ll see the curvature; there are thousands of photos, videos, testimonials, and living astronauts of the time who can attest to the reality of the moon landing. Which leads nicely into the next trait…

02. It has strong evidence and reasoning behind it.

Technically speaking, evidence is just information offered to support or refute a belief. Strong evidence is evidence that:

- Can be observed

- Can be measured

- Can be independently verified

- Cannot be accounted for by other explanations

What We Mean When We Say “Observed.”

When we say strong evidence “can be observed,” we don’t mean only personally observed.

When we say strong evidence “can be observed,” we don’t mean only personally observed.

Reliable observations can come from others. This is especially true when those observations are numerous, consistent, and independently documented. For example, it’s unlikely anyone reading this book is old enough to have personally witnessed historical events like the Holocaust, but we consider them strongly supported by evidence because of the combination of many trustworthy sources: survivor testimony, photographs, documents, physical sites, and film footage, all of which can be independently verified and cross-checked.

For example: Let’s say you want to investigate the belief of “after it rains, the ground is wet.” Strong evidence would be:

- Observing the ground was indeed wet after a storm (and having your neighbors observe the same)

- Measuring the amount of water on the ground before and after it rains

- Having somebody else verify your findings

- Ruling out other possible alternative explanations (such as a neighbor’s sprinkler system going off)

Reasoning is the process by which we analyze and evaluate evidence and arguments. Good reasoning typically involves applying logic, as well as searching for potential flaws, such as biases and logical fallacies.

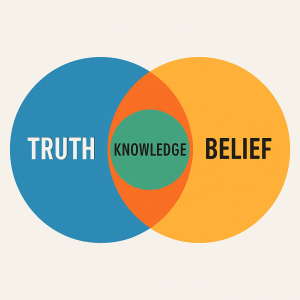

If a belief is based on good reasoning of strong evidence and seems to correspond to reality, we call that belief justified because it has a much higher probability of being true.

Essentially, knowledge is where truth and belief intersect.

Let’s Check!

So, if you determine an idea is a belief and not knowledge, is it still valuable? Yes! We learn a lot about the world by understanding what people believe and why. Beliefs are the catalysts of major events, and they drive much of human behavior, both individually and collectively. Beliefs can also be respected without being shared by all who consider them.

That said, not all beliefs are equally reliable when it comes to making decisions, especially when those decisions affect others. While beliefs matter, they aren’t a substitute for evidence-based knowledge when the stakes are high. Valuing beliefs doesn’t mean treating them all as equally true.

The Burden of Proof

Another important concept when it comes to knowledge and knowledge acquisition is the burden of proof. This is the idea that it’s the responsibility of the person making a claim to provide evidence for it, not the other way around.

To understand why the burden shifts in this direction, let’s use an example:

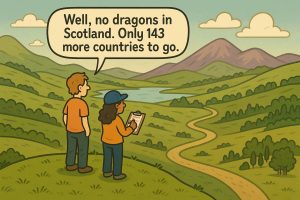

Let’s pretend I come up to you and say, “Dragons are real! I know they’re real.”

Your logical next step might be to ask something like, “why do you believe that? What evidence do you have that dragons are real?” This would be you asserting (correctly) that the burden of proof should be on me. I’m the one claiming dragons exist, so I should be the one to back that claim up with evidence.

But pretend that my response to you is then, “I just do! It’s on you to prove me wrong.”

Outside of this just generally being an annoying way for me to respond, how would you possibly go about proving me wrong? Would you take your entire life to scour every inch of the globe so that you could confidently say “I’ve looked everywhere and I can’t find one”? And even if you did, what would prevent me from then claiming “well, dragons are invisible, so of course you can’t see them”? That pattern could just continue on forever.

This is also a rhetorical strategy called burden shifting — improperly shifting the burden of proof to distract from a lack of evidence for a claim — and it’s frequently used in misinformation materials or by people spreading disinformation. Whenever you hear someone say anything like “prove me wrong,” it’s a good bet you’re dealing with a claim with no evidence to back it up.

Extraordinary Claims

In the late 1970s, science communicator Carl Sagan popularized a notion that went back hundreds of years:

What counts as “extraordinary” will always involve some ambiguity, but the general idea is that different levels of claims require different levels of evidence. The more unlikely a claim is (given our current knowledge), the more evidence is needed before accepting that claim.

Here’s an example:

Pretend your friend told you “I went to the mall last week.” You likely wouldn’t require any evidence from your friend, because there’s nothing extraordinary about the claim. People go to malls all the time, it’s not difficult to go to malls, and so on. Your friend could technically be lying, but you’d probably just take their word for it.

Now pretend that friend told you “I went to the Grand Canyon last week.” That’s a slightly bigger claim than going to the mall, but it’s still perfectly feasible. You might ask to see some photos, but it probably wouldn’t take much to convince you of the claim.

Now, finally, pretend that friend told you “I went to the moon last week.” This person may be who you’re closest with in life, but you would still likely need a lot of evidence to believe them. Even some photos would be unlikely to do the job, as you would rightly assume that it was more likely your friend made fake photos than that they actually went to the moon.

This is, more or less, what we’re talking about with “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” If someone is making a highly improbably claim, you should require a large amount of strong evidence from them to support it.

Why is Epistemology Important?

Epistemology helps our view of the world match closer to reality. When it comes to resisting misinformation, this becomes especially important. A piece of media content might feel true (for a variety of reasons we’ll cover in the following chapters), but that’s no guarantee of it actually being true.

It also helps you think about the strength of evidence that people provide for claims and beliefs, how well (or how poorly) it supports them, and whose job it is to provide that evidence in the first place.

Ultimately, valuing epistemology helps you prioritize doing a little bit of investigation to verify the truth of the content you engage with. In essence, it helps you put a critical eye on your own beliefs, as well as the beliefs of others, so you can better navigate the world.

TL;DR

Chapter Quiz and Short Essay

Knowledge Check: Epistemology

Short Essay: Epistemology

Vocabulary

belief

something a person holds to be true without necessarily having rational justification for it

burden of proof

the idea that it’s the responsibility of the person making a claim to provide evidence for it

burden shifting

improperly shifting the burden of proof to distract from a lack of evidence for a claim

epistemology

the study of how we know what we know

evidence

information offered to support or refute a belief

falsifiable

able to potentially be proven wrong through observation and experimentation

knowledge

something we hold to be true that’s supported by verifiable evidence and reasoning; justified belief

objective

something about the world that can be observed and tested independent of personal feelings

reasoning

the process by which we analyze and evaluate evidence and arguments

subjective

based on personal feeling and preference; cannot be “true” or “false”

Media Attributions

- Why (Version B) © ChatGPT adapted by Kainan Jarrette is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Walking Off a Flat Earth © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Testimony as Observation © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Knowledge Venn Diagram © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- No Dragons in Scotland © ChatGPT adapted by Kainan Jarrette is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- ECEE_01

- Busy Friend © ChatGPT

- Epistemology Text 01 © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Epistemology Text 02 © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Epistemology_Text_03 © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

the study of how we know what we know

something we hold to be true regardless of evidence and reasoning

something we hold to be true that's supported by verifiable evidence and reasoning; justified belief

based on personal feeling and preference; cannot be "true" or "false"

able to be potentially proven wrong through observation and experimentation

something about the world that can be observed and tested independent of personal feelings

information offered to support or refute a belief; strong evidence can be observed, measured, independently verified, and cannot be accounted for by other explanations

the process by which we analyze and evaluate evidence and arguments

the idea that it's the responsibility of the person making a claim to provide evidence for it

improperly shifting the burden of proof to distract from a lack of evidence for a claim

false, inaccurate, or misleading information