Hasty Generalizations

Kainan Jarrette and Diana Daly

What is a hasty generalization?

A hasty generalization is when someone draws a conclusion about a group, trend, or idea based on a small or unrepresentative sample.

Basically, it’s jumping to conclusions based on too little and too weak of evidence (such as personal anecdotes or experience).

You can also think of this in terms of the colloquial English phrase “painting with a broad brush.”

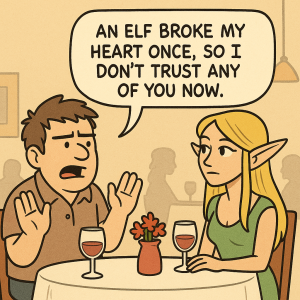

Examples

How to Spot a hasty generalization

Hasty generalizations can be both easy and difficult to spot, depending on the context. Importantly, if the generalization tends to match our existing beliefs, our cognitive bias means we’ll more readily accept it.

Here are some things to look for that may indicate you’re dealing with a hasty generalization:

- Absolutist Language

- Are words like “everyone,” “nobody,” “always,” “never,” “all,” etc. being used?

- Stereotypes

- Does the argument rely on existing stereotypes about a group?

- Personal Anecdotes

- Are the only examples being provided from personal experience?

Anecdotes, Evidence, and Experience

There is a fine line to walk when talking about anecdotes and personal experience. Personal experience is relevant to an individual, as it’s almost certainly shaping that individual’s thoughts and beliefs. The idea is not to entirely invalidate that personal experience can be meaningful. Rather, it’s to acknowledge that personal experience is quite often not as representative of the greater whole as it sometimes feels like.

There is a fine line to walk when talking about anecdotes and personal experience. Personal experience is relevant to an individual, as it’s almost certainly shaping that individual’s thoughts and beliefs. The idea is not to entirely invalidate that personal experience can be meaningful. Rather, it’s to acknowledge that personal experience is quite often not as representative of the greater whole as it sometimes feels like.

Let’s say you get attacked by someone dressed as a clown. It’s reasonable in your subjective experience to develop a nervousness around clowns as a result. However, objectively speaking, your personal experience doesn’t prove that all clowns (or even most clowns) are actually violent.

When Generalizations Are Okay

There are times when generalizations are relatively accurate and can be used. Take, for example, the claim “smoking causes cancer.” We largely accept this as an obvious truth now, because it is generally true. But let’s look at a couple key points that set this claim apart from a hasty generalization:

- There is an overwhelming amount of scientific evidence to support the claim

- There are hundreds of studies and replications done over several decades that support the idea that there is a causal link between smoking and developing cancer.1

- The claim is understood to not be literal, instead meaning “smoking significantly increases your chances of developing cancer”

- If you were to ask most scientists or doctors “does smoking guarantee you’ll develop cancer?” they would tell you no. The claim isn’t seeking to assert something is absolute, only that its likelihood is high enough that it poses a significant risk.

A generalization is usually considered hasty when it lacks sufficient evidence and seeks to be absolute.

Why Hasty Generalizations Matter

Hasty generalizations can have a profoundly negative effect both on a personal level and a broader societal level.

On a personal level, they can lead to bad decision-making. If, for instance, you let one bad experience with a dentist prevent you from ever going to a dentist again, your teeth are likely to suffer as a result.

On a societal level, they can fuel stereotypes and prejudice. They flatten the variation that’s usually seen in most groups into something monolithic, either by asserting that everyone in the group is entirely negative or entirely positive. This type of oversimplification makes misinformation using this fallacy spread quickly and easily.

Ultimately, hasty generalizations undermine critical thinking. When we jump to a conclusion, we’re inherently not doing the work of reasoning.

Look Who’s Talking!

It’s human to jump the gun a little, and make an assertion before there’s sufficient evidence to support it. But if you see a speaker who frequently generalizes complex topics or groups, they’re likely doing so as an intentional rhetorical strategy, meant to manipulate the audience (and shut down debate). This should raise serious red flags, as it undermines their credibility as an accurate source of information.

Knowledge Check: Hasty Generalizations

Vocabulary

hasty generalization

when someone draws a conclusion about a group, trend, or idea based on a small or unrepresentative sample

References

1 Lee, P. N., Forey, B. A., & Coombs, K. J. (2012). Systematic review with meta-analysis of the epidemiological evidence in the 1900s relating smoking to lung cancer. BMC cancer, 12, 385. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-385

Media Attributions

- Hasty Generalization Title © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Don’t Smoke © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Elf Date (Basic) © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Bad Clown © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Painting the Rainbow © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

when someone draws a conclusion about a group, trend, or idea based on a small or unrepresentative sample

the systematic ways our minds can lead us to misjudge, misunderstand, or ignore information

based on personal feeling and preference; cannot be "true" or "false"

something about the world that can be observed and tested independent of personal feelings

false, inaccurate, or misleading information

the practice of carefully analyzing information, beliefs, and arguments in order to make well-reasoned decisions, form justified beliefs, and avoid being misled

any deliberate technique a speaker or writer uses to persuade, influence, or shape how an audience thinks or feels about an issue