Introduction to Critical Thinking

Kainan Jarrette and Diana Daly

What is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the practice of carefully analyzing information, beliefs, and arguments in order to make well-reasoned decisions, form justified beliefs, and avoid being misled. It involves asking thoughtful questions, recognizing fallacies or biases, and being open to revising your views when evidence demands it.

There are some mental tools that make up the building blocks of critical thinking, which we’ll cover in the following chapters:

- Epistemology – How do we know what we know?

- Cognitive Bias – How does the brain trick itself?

- Logic and Intuition – How do we reason clearly and know when analysis is more useful than our gut?

- Media Literacy – How do we apply all of the above to prevent being manipulated by media in our daily lives?

- AI Literacy – How can critical thinking be applied to the presence and use of AI?

What Critical Thinking Is Not

Critical thinking is meant as a tool, not as an identity. Humility and curiosity are vital to critical thinking, which means:

- Critical thinking is not just being “smart.”

- Critical thinking is not being contrarian.

- Critical thinking is not just aimlessly criticizing things.

- Critical thinking is not an excuse to be cynical, snarky, or dismissive.

- Critical thinking is not a guarantee of always being right.

- Critical thinking is not just saying “I’m a critical thinker.”

As we’ll cover more in upcoming chapters, there’s a growing weaponization of many of these terms and ideas. But these tools are not about “winning” or “being better” than anyone. Bullying is not compatible with good critical thinking.

Why Critical Thinking Matters

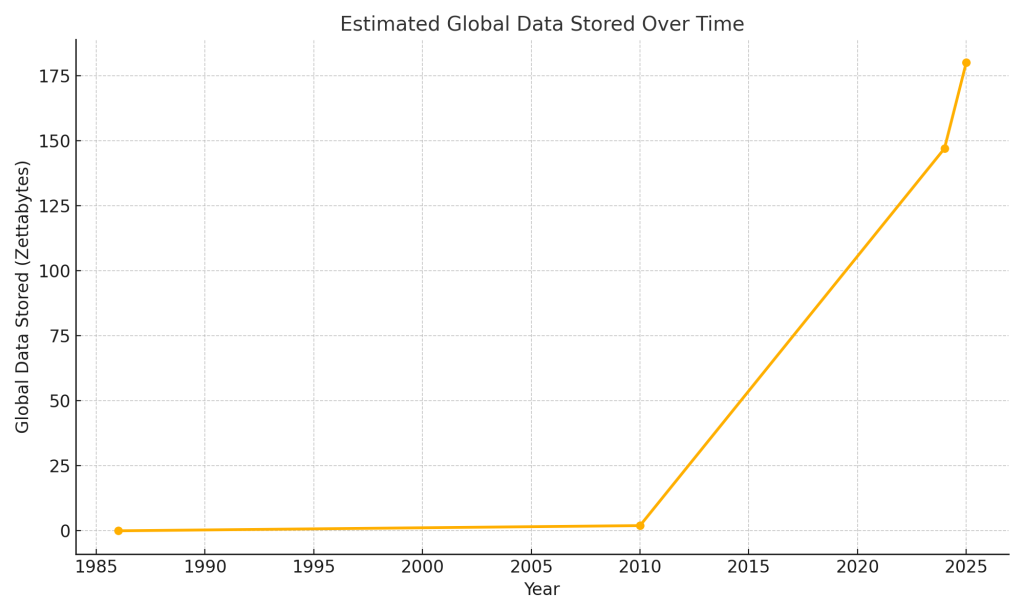

We live in an era of information abundance. Not only has it never been easier to access or share information, but the rate and speed with which that happens is unprecedented in human history. Look at the following progression:

- From 1986 through 2007 it’s estimated that about 295 exabytes1 (or roughly 295 billion gigabytes) of data were stored globally.

- By 2010 that had increased to over two zettabytes of global data (that’s two thousand exabytes, or two trillion gigabytes).

- In 2024 that had increased to 147 zettabytes (so 147 trillion gigabytes).

- By the end of 2025 it’s projected to be over 180 zettabytes2 and climbing.

Unfortunately, this information abundance also means there’s an abundance of misinformation. Misinformation is false, inaccurate, or misleading information and it’s everywhere.

Misinformation, Disinformation, and the Name Game

In other classes, books, and articles you read, you may see both the term “misinformation” and also the term “disinformation.” Many times it feels like they’re used interchangeably, but technically there’s a distinction: intent.

Misinformation is false, misleading, or inaccurate information… but not necessarily with an intention to deceive.

Disinformation is false, misleading, or inaccurate information… but with a specific intent to deceive.

The problem is that it’s often very hard to actually know somebody’s intent. In fact, the same piece of information (meaning its content) can be considered both misinformation or disinformation simply depending on who shared or created it for what reason.

Given all that, this book will generally be sticking to the term “misinformation” for sake of ease.

Misinformation is dangerous because it can affect not only our general view of the world, but the very way in which we think3. Since thinking is always (on some level) the precursor to action, that means misinformation interferes with things like:

- What and how we consume

- How we vote

- How we interact with others

- How we empathize

Which are all activities that are both fundamental for a well-functioning society and fundamental for being a good citizen, communicator, friend, parent, and so on. The tools of critical thinking provide you with a much better defense against misinformation and all the negative consequences it can bring.

Vocabulary

critical thinking

the practice of carefully analyzing information, beliefs, and arguments in order to make well-reasoned decisions, form justified beliefs, and avoid being misled

misinformation

false, inaccurate, or misleading information

References

1 Hilbert, M., & López, P. (2011). The world’s technological capacity to store, communicate, and compute information. Science, 332(6025), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1200970

2 Backlinko. (2023, October 24). How much data is generated per day in 2024? Exploding Topics. https://explodingtopics.com/blog/data-generated-per-day

3 Loftus, E. (n.d.). Misinformation effect. EBSCO Research Starters. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/social-sciences-and-humanities/misinformation-effect

Media Attributions

- Thinking with Question Mark © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- WL Sheldon Quote © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Information Overload © ChatGPT

- Global Data Growth Graph © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

the practice of carefully analyzing information, beliefs, and arguments in order to make well-reasoned decisions, form justified beliefs, and avoid being misled

false, inaccurate, or misleading information