Slippery Slope Arguments

Kainan Jarrette and Diana Daly

What is a Slippery Slope Argument?

A slippery slope argument is when someone asserts that accepting one idea or policy will unavoidably lead to a series of negative outcomes, without showing clear evidence for how or why those outcomes would actually follow.

It’s essentially arguing that “if we take the first step of A, we will inevitably slide into Z.”

The term as a metaphor has been used in various domains for at least a couple centuries, even before its more formal inclusion into logic and critical thinking.

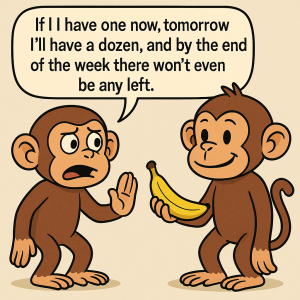

Examples

How to Spot a Slippery slope argument

Believe it or not, there was actually a time when people making this type of argument would just use the phrase “It’s a slippery slope…” Unfortunately, people aren’t usually that obvious anymore. But there’s still inevitability language — the use of words and phrases that suggest something is certain and unavoidable — that can signal you may be dealing with a slippery slope argument. This includes:

- “The next thing you know…”

- “Once we start down this path…”

- “Before you know it…”

- “Where do we draw the line?”

- “It’s only a matter of time before…”

- “First it’s [A], then it’s [B], then it’s [C], then it’s….”

Phrases like this are then followed by some type of exaggerated claim that is many steps away from the original action or policy being discussed.

For example, if you said “If you take a shower, then you’ll be wet” that wouldn’t involve any type of slippery slope. Being wet is the logical consequences of taking a shower. But if you said “If you take a shower, then you’ll slip in the water and break your head” that is a slippery slope (no pun intended). Injuring yourself is not a typical consequence of taking a shower.

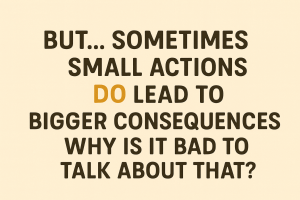

There are Valid Chain-of-Consequences Arguments

Some readers may understandably be thinking to themselves at this point:

The answer is: it’s not! Not every chain of consequences is a slippery slope. It’s only fallacious when the argument jumps from a minor premise to a major conclusion without sufficient evidence or reasoning.

Here are some components of a valid chain-of-consequences argument, as opposed to a slippery slope:

| Component | VALID ARGUMENT | SLIPPERY SLOPE |

|---|---|---|

| Each step in the chain is supported with evidence and reasoning. | “If we remove these safety regulations, then more accidents will happen, because reports by the Consumer Product Safety Commission indicated that those regulations had reduced accidents after they were implemented.” | “If we remove these safety regulations, then lots of people will die. Just think about it!” |

| Intermediate steps in the chain are acknowledge and explained. | “If we remove these safety regulations, then more car accidents will occur. If more car accidents occur, then insurance rates will likely go up. If insurance rates go up, you’ll have less disposable income.” | “If we remove these safety regulations that just means less money in your pocket!” |

| The progression of the chain is both possible and probable. | “If more car accidents occur, insurance rates are likely to go up.” | “If more car accidents occur, they’ll just start outlawing driving altogether.” |

Why Slippery slope arguments Matter

When you sit down and logically work through a slippery slope argument, the error in reasoning is often fairly obvious. However, slippery slope arguments tend to make claims that aren’t just exaggerated, but are emotionally charged. As we discussed in earlier chapters, arguments that appeal to our emotions can easily circumvent rational thinking.

This means slippery slope arguments can be very good at taking advantage of other cognitive biases like:

- Loss aversion – our tendency to feel the pain of a loss more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain

- Status quo bias – when faced with a decision involving change, we tend to choose the option that keeps things as they are, even if there may be benefits to alternatives

- Moral panic – a disproportionate reaction to a perceived social problem, where the fear is often greater than the actual threat

Progress and advancement are important, be it culturally, politically, economically, etc. This doesn’t mean every idea for change is good, but the only way to work that out is by logical reasoning through the idea. Slippery slope arguments hijack our emotions to manipulate us into favoring what we know over what we don’t, so that we never even do the work of reasoning.

Look Who’s Talking!

Sometimes our emotions can get the better of us and we can leap to a conclusion without good reasoning. But if you see a speaker who frequently seems to argue extreme or exaggerated outcomes as a consequence of small actions, they’re likely doing so as an intentional rhetorical strategy, meant to manipulate the audience. This should raise serious red flags, as it undermines their credibility as an accurate source of information.

Knowledge Check: Slippery Slope Arguments

Vocabulary

inevitability language

the use of words and phrases that suggest something is certain and unavoidable

loss aversion

our tendency to feel the pain of a loss more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain

moral panic

a disproportionate reaction to a perceived social problem, where the fear is often greater than the actual threat

slippery slope argument

when someone asserts that accepting one idea or policy will unavoidably lead to a series of negative outcomes, without showing clear evidence for how or why those outcomes would actually follow

status quo bias

when faced with a decision involving change, we tend to choose the option that keeps things as they are, even if there may be benefits to alternatives

Media Attributions

- Slippery Slope Title 01 © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Bowtie at Work © ChatGPT

- No Bananas Please © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Slippery Slope Text 01 © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Communication Slipping © ChatGPT is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

when someone asserts that accepting one idea or policy will unavoidably lead to a series of negative outcomes, without showing clear evidence for how or why those outcomes would actually follow

the use of words and phrases that suggest something is certain and unavoidable

the systematic ways our minds can lead us to misjudge, misunderstand, or ignore information

our tendency to feel the pain of a loss more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain

when faced with a decision involving change, we tend to choose the option that keeps things as they are, even if there may be benefits to alternatives

a disproportionate reaction to a perceived social problem, where the fear is often greater than the actual threat

any deliberate technique a speaker or writer uses to persuade, influence, or shape how an audience thinks or feels about an issue