Introduction

Diana Daly

Introduction

This book has come about at a peculiar time in social history. Humans have long thrived from sharing information and narratives with one another, in familial and social groups and networks. Discovering and sharing information— that which is both known to be true and able to be transferred—has helped people heal from disease, build societies together, and coexist. A narrative, or story, wraps that information up in an immersive, memorable bundle. This method of bundling and sharing information has likely benefited humans for as long as we have existed.

A great deal of storytelling has blended information based in reality with other elements. Subjectivity, emotions, made up examples, and even outright fantasy can be part of storytelling, with the core information conveyed by the story still true. It has also long been possible for stories to spread harmful content including all manners of misinformation.

What is peculiar today is that we are in an era in which narratives spreading in groups are more and more likely to be found eroding the same human projects they once helped build, like democracy, public health, and scientific advancement. While damaging narratives have always been part of history, in the past those with the broadest reach were likely to be created and spread by governments. Popular narratives would spread more gradually, often through populations that would mix skeptics and believers. The moment we are in now is remarkable for the speed with which a bad narrative can crackle across a vast network of believers.

Learning Objectives

Your goals in the chapter are to:

- Be able to define Information-related concepts used in this book.

- Identify examples of how stories, group identity, and online affordance activation work together to spread disinformation

- Learn what the Immersive Truth project is about, who is involved, and how others can use the same techniques to benefit society.

- Reflect on how we tell the stories that define us.

Defining Features: Making Sense of Important Terminology

Although often used interchangeably in popular media, misinformation, disinformation, malinformation, and propaganda technically have some very important differences, as well as some challenges in how and when they’re applied. Here, we’ll define what we mean by each:

- Misinformation is inaccurate information, but without any conscious intent to deceive the audience.

- Disinformation is inaccurate information, but with the intent to deceive the audience.

- Malinformation is inaccurate information with the intent to not only deceive the audience, but to cause harm to a specific person or group of people.

- Propaganda is manipulated or misleading information created or spread by organizations or groups to have broad social or political impacts.

One of the major difficulties with these terms is that they largely revolve around the idea of intent, an aspect that is often very difficult to determine with good accuracy.

Further, one piece of content can be shared and disseminated by many people, each of whom may have their own motivations. For instance, let’s say someone (Author X) creates a piece of media content with false information with the express intent of harming a particular group. Well, in that context, Author X has created a piece of malinformation. But, let’s say after that content is originally posted, it’s seen and shared by someone else (Viewer Y). Viewer Y believes the information in the content to be true, and so shares it with no intent to deceive. In that context, we’re speaking of misinformation — and yet the content of the information hasn’t changed. Similarly, disinformation initially created by an entity other than an organized group may become propaganda if an organized group takes it up as useful to their cause and spreads it.

Given all of this, it should be noted that when we use the term misinformation in this book we are not asserting that there is definitely not intent, only that we don’t have enough evidence to claim otherwise.

Narrative, Group Identity, and Online Affordances: The Disinformation Triad

There is a powerful triad behind the disinformation spreading in online networks today: The three elements of what we will call the Disinformation Triad are narratives, group identity, and activation of online affordances. None of these elements is inherently bad, and this triad can also work together in ways that benefit social cooperation. But when the elements of this triad are deployed driven by harmful intent, this triad’s power to weaken social institutions is formidable.

Let’s meet these elements by imagining them on a theater stage.

Enter the Narrative, stage left.

Enter the Narrative, stage left.

We all know the Narrative, and have since the dawn of human history. In fact, we know her so well we can call her by her nickname: a story. Stories can be structured in many different ways, but typically they involve a sequence of connected events and associated meanings. A story is usually presented using the subjectivity of someone who witnessed or participated in those events, whether that perspective is first person (“I”, “We”), or second person (“They”,”She”, “He”, “It”.)

Are stories still transmitting good quality information in societies today? Yes! In the United States where this book is focused, parents, schoolteachers, librarians, and all manner of content creators share essential information through stories. Some important histories are only available through stories, such as oral histories. While other forms of information sharing exist—think of a written list, or a bus schedule— stories have been found to be uniquely effective both at convincing people to believe information and then helping people remember it. This is the upside of using narratives to teach: Stories are sticky.

Enter Group Identity, stage right.

Group identity gives narrative a strong point of view, and also the motivation to believe and spread the story. Consider for a moment only stories that are true, or based primarily on evidence. True stories we know and share are so important in our lives that they help define us, like signatures on our minds, even as we coexist with people who have different signatures on their minds. For example: How was the nation where you were born created? Your answer to this question will be based on a story, and that story will say a lot about your identity group, including whose stories you believe and ultimately who you are. This subjectivity in history is not new. A look at conflicts among historians reminds us that some conflicts around evidence and interpretations of the past are never fully resolved, and each conflicting accounts is believed and championed by an identity group.

Misinformation can often begin with true stories championed by a group, whose members are motivated to believe and emphasize parts of the story that reinforce their beliefs. Those who identify with one another may communicate in echo chambers least in part because of the group identities those narrative express and create. People are motivated to believe what others they identify with believe, to avoid the discomfort of disagreeing with people they value and relate to. They quickly accept or invent new stories that help them avoid feelings of aloneness, or fear, or cognitive dissonance. Those stories can bond them and explain away more complex, depressing realities.

Enter Online Affordances, backstage.

Misinformation circulating in online networks is also driven by the sense that people should “do their own research” rather than trust the institutions that have historically promoted public health and reliable information. This popular research then meets up with features of the internet that further influence what people do online, or affordances. Search engines are designed to respond to prompts whether or not they have true answers, and they have so much content that if you “do your own research,” you can use them to find anything you’d like to be true.

In short, there is a powerful triad that fuels the rapid, deep, and broad spread of disinformation online. The good news is that this triad can work for true and beneficial information too, if we understand how the triad works.

We can take out the misinformation, but leave in those powerful dynamics. That is the premise of this book, and of the project this book invites you to join in.

Key Terms

signals or cues in an environment that communicate how to interact with features or things in that environment

the uncomfortable feeling that arises when something you already think clashes with something new you learn

inaccurate information, but with the intent to deceive the audience

a situation in which beliefs are amplified or reinforced by communication and repetition inside a closed system and are insulated from rebuttal

inaccurate information with the intent to not only deceive the audience, but to cause harm to a specific person or group of people

inaccurate information, but without any conscious intent to deceive the audience

a story; a sequence of connected events and associated meanings

manipulated or misleading information created or spread by organizations or groups to have broad social or political impacts.

blaming a person or group that cannot defend themself for a problem they did not actually cause (From Reinhardt et al, 2023)

Immersive

To be deeply surrounded and absorbed by something

Truth

based in reality, independent of anyone’s perspective

Storytelling about a nation

Let’s try an exercise.

- Write or record yourself telling the story of how the nation where you were born or that you most identify with was created, for one minute.

- Now, review your story and reflect on what it says about you.

- Who is/are the protagonist[s] or main character[s]?

- When does the story start and when does it end?

- What is the main action that happens in the middle, and what emotion[s] does it evoke or cause?

- Next, tell the story with each of those elements changed.

- Make the protagonist[s] or main character[s] someone culturally different than who they were before.

- Recreate the story in that character’s perspective, including not only the time period of your original story but also events before and time after.

- How do the above changes impact the main actions and emotions in this new telling of this story?

Teachers, this exercise may look very different for students who are not part of the dominant culture represented in the class than it does for most of the rest of the class. Please consider carefully before collecting or sharing this exercise.

Media Attributions

- Planta Tartara Barometz (or the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary) © Henry Lee is licensed under a Public Domain license

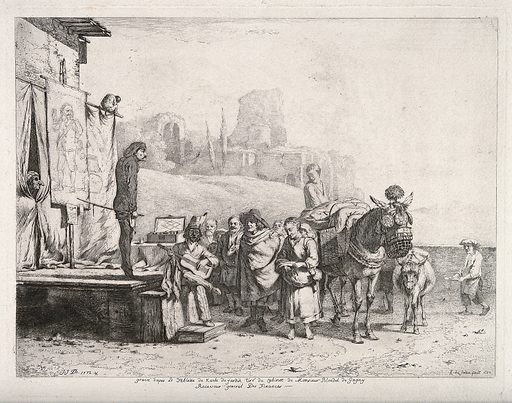

- A group of itinerant actors performing on stage in an attempt to sell medicines to a small group of people. © Etching by JJ de Boissieu, 1772, after K Dujardin, 1687. is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

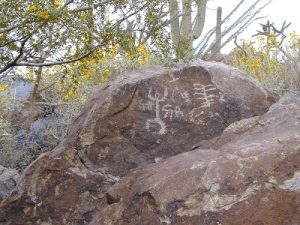

- Rock Art Panel 6 © National Park Service is licensed under a Public Domain license

that which is both known to be true and able to be transferred

a story; a sequence of connected events and associated meanings

inaccurate information that is spread without the intention to deceive

information intended to deceive those who receive it

inaccurate information with the intent to not only deceive the audience, but to cause harm to a specific person or group of people

manipulated or misleading information created or spread by organizations or groups to have broad social or political impacts.

contexts in which one is surrounded by those expressing similar beliefs, leading those beliefs to grow stronger and more resistant to changing in the face of new information

the uncomfortable feeling that arises when something you already think clashes with something new you learn

signals or cues in an environment that communicate how to interact with features or things in that environment

a situation in which beliefs are amplified or reinforced by communication and repetition inside a closed system and are insulated from rebuttal

blaming a person or group that cannot defend themself for a problem they did not actually cause (From Reinhardt et al, 2023)

to be deeply absorbed and surrounded by something

based in reality, independent of anyone's perspective