Universal Topics

4 Critical Legal Studies

Jennifer Allison

This chapter discusses critical studies and their manifestations in librarianship and law. It provides law librarians with a framework for thinking critically about law libraries and encourages them to center equity, compassion, and justice in their practice of law librarianship.

- Critical studies are a method for deep, ethical, and meaningful thinking about new and emerging problems and engaging in intellectual exercises that challenge the status quo.

- It is crucial to view librarianship critically because libraries and librarians are neither neutral nor unbiased, despite public perception to the contrary.

- Critical legal studies have emerged for many other racial/ethnic identity groups: Latina/o/x critical theory, Asian critical theory, critical Indigenous studies, and critical whiteness studies.

Critical Studies as a Scholarly Discipline

Critical Studies Terminology

Critical studies are a method for deep, ethical, and meaningful thinking about new and emerging problems and engaging in intellectual exercises that challenge the status quo. Scholars in many academic disciplines engage in “critical” studies–from anthropology to sociology, linguistics to psychology, and urban studies to political science. These scholars commit themselves to researching and thinking about topics, concepts, and phenomena in ways that challenge mainstream and generally accepted norms and standards. What it means to engage in “critical” scholarship differs from field to field and from place to place and time to time.

As a discipline, critical studies is primarily concerned with three phenomena:

|

As with any academic discipline, critical studies have their own vernacular. Selected key terms are defined in the chart below.

| Term | Definition |

| Critical Theory | A school of thought involving critical assessment of a social phenomenon to determine how it impacts the freedoms of those in society. |

| Hegemony | When a dominant group exercises power over other groups, dictating the cultural and social behavioral norms. |

| Heterodoxy | Engagement with thinking or ideas that run counter or opposite to what is considered orthodox, standard, or normal. |

| Liberalism | A political philosophy consisting of three core elements: individualism, private property ownership, and democracy. |

| Marxism | A political and philosophical theory developed by Karl Marx that seeks to eliminate social inequality that is created by the class system that emerges in capitalist societies. |

| Pluralism | The idea that economic and political power should be shared equally between various groups rather than being vested in an elite central entity. |

| Praxis | Engaging in direct, intentional action to counter or destroy a hegemonic, oppressive system and the inequities it creates. |

| Radical | A descriptive qualifier for an idea, a line of thought, or a movement that runs counter to and challenges the mainstream order |

Critical Librarianship

As with other disciplines in the social sciences, librarianship provides a rich foundation for critical studies scholarship. It is crucial to view librarianship through a critical lens because libraries and librarians are neither neutral nor unbiased, despite public perception to the contrary.

The foundation of western librarianship is a white male hegemonic infrastructure. This means that the library as we know it today was created by white men who centered the organizational system of librarianship around their (white, cis-male, heterosexual, Christian, able-bodied) understanding of the world. The result is that print and electronic materials in library collections and the language used to describe, organize, and find them, often omit, exclude, and offend library users. There are many examples of how this phenomenon manifests itself; in this discussion, we will focus on two of them: library catalogs and database indexing and retrieval.

Library Catalogs

Since the 1970s, librarians have been critically examining how white male hegemony is perpetuated in library catalogs. One of the leaders of this movement was cataloger Sanford (Sandy) Berman at the Hennepin County Library in Minnesota. His 1971 book Prejudices and Antipathies: A Tract on the LC Subject Heads Concerning People addressed what he saw as a major problem in the Library of Congress’s subject heading list.

As Berman explained, this list could only “’satisfy’ parochial, jingoistic Europeans and North Americans, white-hued, at least nominally Christian (and preferably Protestant) in faith, comfortably situated in the middle- and higher-income brackets, largely domiciled in suburbia, fundamentally loyal to the Established Order, and heavily imbued with the transcendent, incomparable glory of Western civilization.”

| A particularly problematic term in the LCSH list is “illegal aliens.” In response to a student-led protest over the use of this term in the library catalog at Dartmouth College in 2013, the Library of Congress decided to change this subject heading to “undocumented immigrants” in 2016. This change, however, was rejected by Congress. Since that time, some libraries have made this switch in their own local catalogs. |

The book calls for the elimination of many egregiously-offensive LCSH terms, including “YELLOW PERIL” (a racist “affront to the people so labeled”), “MIXED BLOODS” (a subdivision of “Indians,” it “represents shoddy science and the White Man’s hauteur”), and “MAMMIES” (“antebellum plantation slang” insulting to African-American women).

Berman addressed not only identities but also phenomena, such as the LCSH term “LYNCHING.” Astonishingly, the only “xx” entry under this term was “Criminal Justice, Administration of.” Berman rightly called for the immediate addition of several other “xx” entries for “LYNCHING”: “Homicide,” “Murder,” “Offenses against the person,” “Terrorism,” and “Violent Deaths.”

Database Indexing & Retrieval

More and more library materials are digitized and accessed through databases, introducing an additional concern for critical librarianship. How are these materials indexed and retrieved? Do these operations aid critical research or hinder it?

In 1989, Professor Richard Delgado of the University of Wisconsin School of Law and Jean Stefancic, Technical Services Librarian at the University of San Francisco Law Library, published Why Do We Tell the Same Stories?: Law Reform, Critical Librarianship, and the Triple Helix Dilemma in the Stanford Law Review. This article explores how the LCSH system, law journal indexes, and the West Digest System comprise the classification system that legal researchers use to find and describe the law and legal ideas. Delgado and Stefancic argue that this system inhibits looking at the law in new, fresh, critical ways because it “replicate[s] preexisting ideas and approaches[,]… mak[ing] foundational, transformative innovation difficult.”

Adding to the challenges in today’s database landscape is the use of algorithms to index and locate materials. These algorithms presumably work in ways meant to “help” researchers get “relevant” search results. Critical scholarship on this topic by law librarians reflects two major areas of concern. First, if these algorithms favor crowdsourced results, how does that hinder a critical researcher’s ability to view problems and create solutions with a fresh perspective? Second, not only is the exact operating procedure of the algorithm something of a mystery, but the algorithm incorporates its programmer’s inherent biases. How does this lack of transparency cloud a researcher’s critical lens, and can any biases inherent in the algorithm be overcome?

Our Responsibilities

We who work in libraries must view the selection and description of library materials through a critical lens that recognizes inequity and injustice, and work to change library infrastructures that demean, discriminate against, injure, and exclude people.

To fulfill this obligation, we must first acknowledge that libraries were created to reflect and further a white male hegemony. This acknowledgment creates two responsibilities:

| Responsibility #1

We must work compassionately with our users to help them maximize their success in navigating the library as it currently is. |

Responsibility #2

We must work to eliminate aspects of the library that reflect and further societal marginalization and oppression. |

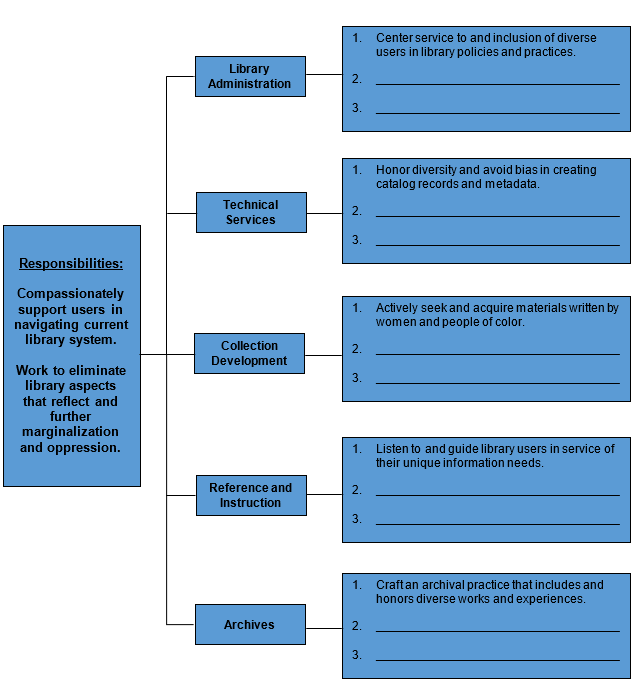

Critical Librarianship Across the Library

What can people who work in libraries do to fulfill these responsibilities to our users? The chart below can be a helpful tool in starting a conversation about this.

Critical Legal Studies

What does it mean to call legal studies “critical”? In a 2012 article in the Harvard Journal of Racial and Ethnic Justice, Law professor Lolita Buckner Inniss defined it as follows: “’Critical,’ in this sense refers to closely inquiring into the nature of a thing or idea, not necessarily to alter it or undermine it, but rather to problematize it, that is, to expose vital questions and problems to a thing or concept.”

In the same article, Professor Buckner Inniss goes on to describe three key characteristics of critical legal studies, which can be characterized as follows:

| Using law to solve problems requires recognizing and honoring multiple identities and interests across a spectrum | Legal principles cannot be universally applicable, unless such application empowers historically marginalized and oppressed people. | Law must not be viewed in a binary sense, in which people make right or wrong choices regardless of their personal circumstances. |

This section provides an overview of critical legal studies as an academic discipline. It then discusses various manifestations of the discipline, including critical race theory. It concludes with a brief introduction to the concept of intersectionality.

Historical Development

Legal thought in the United States developed in three stages. The first, Classical Legal Thought (1800s-1920s), also called legal formalism or legal orthodoxy, centers on a uniform, impartial process of legal reasoning. It was mainly concerned with creating a system of fundamental principles about morality, society, and justice to address legal issues. This was followed by the Legal Realism movement (1930s-1960s), which introduced the idea that social forces can and should influence legal change. Influenced by developments in the social sciences, legal scholars explored how law and policy could be crafted to further the public interest.

Beginning in the 1970s, critical legal studies developed as a way to view law through an even broader lens than legal realism and to analyze systemic problems and inconsistencies in legal theory. Scholars of this emerging discipline were encouraged to explore radical alternatives to the current legal order.

In 1982, the first-ever critical legal studies symposium was held at Stanford Law School. The symposium issue published in January 1984 by the Stanford Law Review includes many articles considered fundamental works of the movement.

Critical Race Theory & Critical Legal Studies Sub-Disciplines

In 1995, Professor Derrick Bell, the first tenured African-American faculty member at Harvard Law School, developed critical race theory. Professor Bell defined the discipline as “a body of legal scholarship, … a majority of whose authors are both existentially people of color and ideologically committed to the struggle against racism, particularly as institutionalized in and by law.”

Critical race theorists explore subjects, events, groups, laws, and legal principles, including but not limited to civil rights, voting rights, housing, and employment discrimination, policing, and mass incarceration, through the lens of historical and current injustices that the American legal system inflicts on African Americans. Critical theorists aim to expose injustice and identify alternatives to the current legal order to eliminate those injustices.

Today’s legal scholars explore many areas of law critically. Critical legal studies have emerged for many other racial/ethnic identity groups: Latina/o/x critical theory, Asian critical theory, critical Indigenous studies, and critical whiteness studies. Feminist and queer legal theory scholars explore how the law discriminates against people based on their sex, gender, and sexual orientation. Legal scholars are also engaged in critical disability studies, which explores injustices experienced by people with physical and mental disabilities.

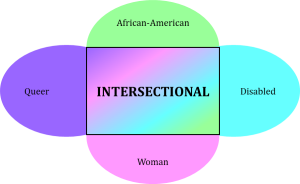

Intersectionality

Many people identify with more than one demographic that experiences discrimination, bias, and oppression, not only in society at large but also in the legal system. In scholarly literature, the term “intersectionality” is used to analyze issues related to identifying with more than one marginalized group.

Professor Kimberle Williams Crenshaw established the concept of intersectionality in a 1989 University of Chicago Legal Forum article, Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Policies. According to Professor Crenshaw, the critical legal studies scholarship up to that point “erases Black women”: critical race theory focuses on the legal system’s treatment of “sex-privileged” Blacks (Black men), while feminist legal theory focuses on the legal system’s treatment of “race-privileged” women (white women).

Why is a separate category like “intersectionality” needed? Professor Crenshaw argues that “the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism.” Intersectional scholarship provides a better framework for focusing on the unique inequities and injustices the legal system creates and perpetuates for Black women.

In addition to the works cited in this chapter, please consult the following for additional information on this topic.

- “Critical Legal Studies Research Guide,” Jennifer Allison, Harvard Law School Library, https://guides.library.harvard.edu/critical-legal-studies [https://perma.cc/VPP9-554T].

- Kate Adler, Ian Beilin, and Eamon Tewell, eds., Reference Librarianship and Justice: History, Practice & Praxis (Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press, 2018).

- Steven M. Barkan, “Deconstructing Legal Research: A Law Librarian’s Commentary on Critical Legal Studies,” Law Library Journal 79 (1987): 617-637.

- Nicholas Magnanelli, “Critical Legal Research: Who Needs It?,” Law Library Journal 112 (2020): 327-343.

- K.R. Roberto, ed., Radical Cataloging: Essays at the Front (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2008).

- Roberto Unger, The Critical Legal Studies Movement: Another Time, A Greater Task (New York: Verso, 2015).

- Virginia Wise, “Of Lizards, Intersubjective Zap, and Trashing: Critical Legal Studies and the Librarian,” Legal Reference Services Quarterly 8, nos. 1-2 (1988): 7-28.