Academic Law Librarianship

9 Technical Services

Carol Morgan Collins; Iantha Haight; and Christy L. Smith

Technical Services departments manage the library’s physical and electronic resources, including all the recordkeeping relating to the resources. Processes include acquisitions, cataloging, electronic resource management, and serials management. Technical Services librarians work closely with publishers, vendors, and collection development librarians in negotiating license agreements, creating approval plans, generating order service plans for the facilitation of data exchange between vendor platforms and the library service platform (LSP), making local cataloging specifications and modifications for services, and troubleshooting electronic resources issues.

- Working in law library technical services requires special tools and skills and differs from other libraries in essential ways.

- Acquisition processes utilize different vendor platforms, purchase orders, and models.

- Web technologies are inspiring innovative services and methods for providing patron access to information.

- Licensing and providing access to electronic resources is taking up an increasingly large portion of library resources.

Depending on the size of the library’s collection or budget, the work can involve a few people or several people. Over the years, technical services have evolved from mostly print resources management to mainly electronic resources management. Some skills are transferable from the print environment to the electronic environment, but employees need to understand how electronic resources are managed as well as how the library’s patrons use them.

Acquisitions

Acquisitions includes the processes involved with purchasing or licensing content for the research, learning, or teaching needs of students, faculty, and other constituencies. Processes include ordering, negotiating, renewing, or canceling titles; paying for resources; and maintaining records. Acquisitions are guided by the library’s collection development policy and usually led by a librarian who understands acquisitions processes and how to make the resources discoverable and accessible.

Types of Orders

Academic law libraries initiate different types of orders. Firm orders are one-time orders for monographs or other resources not normally updated. Subscriptions are orders for resources published on a regular frequency, such as journals or databases that offer service on an annual basis. Standing orders are for titles that are updated but not necessarily on a set frequency. Approval plan orders are usually for monograph titles received on an approval plan. Package plan orders allow the library to receive all publications published by the publisher. Bundled orders include print and electronic subscriptions that are purchased as a package.

As the law changes, publications must incorporate the changes in a timely manner. Because the law can change at any time, publishers sell print primary resources and treatises as standing orders, which means that the publisher or vendor automatically sends any new content as it is published. Some libraries choose to receive a notification, instead of the material, when there is a new update. The library then decides whether to purchase the update. If the library fails to respond to the notification, it will miss the update, and the set becomes outdated.

Libraries set up approval plans with vendors to automatically receive titles or notification of new titles published based on certain library-selected criteria. Criteria may include or exclude certain subjects, call numbers, formats, costs, publishers, series, and more. Approval plans can be for print books, e-books, or both. Libraries choose and only pay for the titles they keep.

Package plans include both serials and monographs published by a specific division or section of the publishing company. The library automatically receives the publications, and the charges will vary based on what titles are included in the shipment.

Legal publishers who sell both print and electronic resources may bundle orders for libraries so that the library can have both formats. For example, Thomson Reuters offers various plans that allow libraries to purchase discounted print materials if they also purchase electronic content, such as Westlaw Patron Access. Publishers include a reduced annual price increase if a library purchases a bundled deal. While these bundled plans are considered cost savings, they also require the library to sign a multi-year agreement. The downside to multi-year agreements is that those titles included in the contract are not ideal candidates for cancellation when budget issues arise.

Purchase Models

Libraries use a book vendor that sells books published by several different publishers to purchase print or electronic books. Book vendor databases provide bibliographic, access, and cost information about books they sell. The databases provide a platform for libraries to order titles and obtain collection development reports (costs, titles purchased in specified call number ranges, subjects, series, formats).

Book vendors sell e-books using a variety of purchase models. Some vendors sell e-books as individual titles or e-book packages that can be digitally borrowed or accessed by one user or simultaneously accessed by multiple users or an unlimited number of users. Some sell Digital Rights Management (DRM)-free e-books and some that are not DRM-free. Vendors may sell the e-books with perpetual access, metered access, or some other type of leased access. Metered access limits the number of check-outs or the time period in which the library may have access to the book. Vendors may charge annual hosting fees for access to the e-book platforms used to read the digital editions or they may charge the purchase price each subsequent year of access.

Demand-driven acquisition (DDA) and patron-driven acquisition (PDA) plans are two types of just-in-time purchase models that allow libraries to make titles discoverable to users through the catalog. The vendor only charges the library when a substantial use triggers a purchase. Substantial use options are defined by the vendor and include events such as downloads, time spent accessing the e-book, number of short-term loans, and more. Libraries set up specifications similar to approval plans and activate or import bibliographic records so that they are discoverable in the library services platform (LSP). Once the content is used, the vendor invoices the library for the e-book. If the e-book is not used, the library does not pay for it and the records are removed from discoverability at the end of the license term. Plan models vary among vendors but using this acquisition method allows users to participate in collection development unknowingly. And it ensures that the library only pays for what is used.

CONCEPT IN ACTION: DEMAND-DRIVEN ACQUISITION

Marcella, a 2L, searches the library catalog for the book Global Health Law. She finds a link for an e-book and opens it. This e-book is part of the library’s DDA collection, but she is not aware of this. She downloads Chapter 2. The download is considered a substantial use, triggering a purchase. The e-book is removed from the DDA collection and made a part of the regular e-book collection. The library is then billed for the e-book. Marcella, unaware that her use has created a purchase for the library, is happy to find what she needed quickly.

Evidence-based acquisition (EBA) plans require an up-front fee for access to a collection of a publisher’s pre-selected titles. The titles are made discoverable in the LSP. At the end of the license term, librarians evaluate usage and select titles, up to the amount of the up-front fee, to permanently add to its perpetual access e-book collection.

Purchase Orders, Budgets, & Receiving

Libraries create purchase orders (also known as order records) that are manually entered or imported into the LSP. Libraries can import bibliographic, order, and invoice data from the vendor’s platform into the library’s catalog and acquisition system, which are standard modules of an LSP.

Purchase orders expense to the library’s collections budget. Collection budgets are established in a variety of ways, depending on the library and institution. Many library budgets are devised based on the formerly asked questions in the annual American Bar Association Questionnaires. Libraries reported how much money was spent on print, electronic resources, monographs, serials, and microforms. Libraries may also divide the budget by subjects or any other meaningful way.

Upon receipt of the ordered item, a library will manually mark the purchase order as received in the LSP, or the status will update via a data exchange between the LSP and the vendor’s platform. The title is then sent to the cataloging department. Some libraries create and email or post bibliographies of new resources received.

Collection Management

Collection management is the process of ensuring that the library’s print and electronic resources are correctly updated, maintained, and accessible such that the collection meets the requirements of Standard 606 of the ABA standards for approval of law schools.i For many print primary and secondary resources, updating is required, and this is a significant difference between law library and regular academic library collections.

Updates

Purchasing the updates requires a healthy budget line for print continuations. The print updates increase in cost each year from 3% to 15%. Many of the titles that require updating are also online in Lexis, Westlaw, or other databases, so libraries need to decide if there is a need for duplicating formats.

Properly updating print resources can be challenging. Publishers periodically ship supplements as the law changes. Types of supplementation include advance sheets, pocket parts, stand-alone supplements, legislative service pamphlets, replacement volumes, packages of loose-leaf pages, errata sheets, and updated book covers.

After receiving print supplementation, a staff member files it. Filing methods vary based on the kind of supplement. For example, publishers update many state statutes with annual pocket parts or stand-alone supplements, periodic replacement volumes, and legislative service pamphlets. The publisher issues pocket parts that contain several pages stapled together. The stapled bundle of pages is about 8” in height and 6” in width and includes a heavy-duty backing that can be inserted into a precut pocket in the back of the volume it updates. When a pocket part is too thick for the book pocket, the update is issued as a stand-alone, paperback supplement that is placed next to the volume it updates.

CONCEPT IN ACTION: HAZARDS WITH LOOSE-LEAF FILING

Anthony is reading §13:15 in the loose-leaf treatise McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition. The last sentence on the page starts with, “People who happen to have a surname similar to.” When Anthony turns the page to read the rest of the sentence, the next page starts with §13:14 and a new sentence. He flips through a few more pages and notices that although the page numbers appear correct, the text on other pages is also out of order. He is baffled and asks a librarian for assistance. After turning to the filing instructions for the loose-leaf release updates, the librarian discovers the filing instructions for release 11, 13, 14, and 15, but not 12. Further investigation reveals that the library never received release 12. The filer forgot to verify the filing of the previous release 12 before filing release 13. The librarian found that the entire set’s contents are out of order due to the failure to file release 12 before releases 13, 14, and 15. The loose-leaf title is a key treatise for library users, so the library decides to replace the set even though it will cost $7,900. Due to the unexpected expense, the continuations budget line will go over budget by $7,900 and other resources may be eliminated to compensate for the extra cost.

When the stand-alone supplement becomes too thick, the publisher issues a new replacement volume that contains the most current version of the law. The filer will replace the old volume that is now outdated with the new replacement volume. Because a set of statutes may have several volumes that have been replaced, the copyright dates on volumes may differ. The publisher also ships legislative service pamphlets when laws are changed during legislative sessions. When new pocket parts are received, the legislative service pamphlets are discarded because the laws are now included in the pocket parts. The updating process then repeats.

Filing requires attention to detail. If mistakes are made, they can be costly to both the researcher using the materials and the library. If a loose-leaf set is filed out of order, and the library cannot track where filing went wrong, the library may have to purchase an entirely new set.

The beauty of electronic resources is that the publisher or provider updates the content. However, library staff must ensure that the links to the electronic resources are accurate so that the researcher is taken directly to the resource or article after institutional authentication.

Space Planning

For physical space planning, librarians measure for growth and weed outdated and irrelevant materials. Librarians use a variety of tools to manage collection space. They measure growth for continuations by reviewing current subscriptions and standing orders, identifying the number of volumes received per year, and then multiplying the number of volumes by the average volume size. They measure growth for monographs by evaluating call numbers of books added to the collection during a given period and multiplying the number of volumes added by the average book size. Librarians also weed resources, as dictated by the collection development policy, to manage space and ensure collection relevancy.

Preservation

Libraries need to preserve materials that they want to keep so that the books or other physical resources do not fall apart or become too fragile for use. Some libraries employ dedicated staff who preserve materials or send materials to the main campus library preservation department. Other libraries use commercial binderies or other entities for preservation services.

Libraries that have special collections may need to invest more heavily in preservation. Special collection preservation expenses can become particularly expensive if the room or facility requires climate control. Libraries that have microforms may want to store them offsite in a commercial facility specializing in the storage of that format.

Cataloging

Processes

Cataloging and classification are the processes that permit effortless and time-efficient retrieval of information and materials. Catalogers use international standards to create and edit bibliographic records and metadata as a service to law communities who expect online, remote access to information, notably full-text data. While the cataloging mission and core principles have remained the same over time, codes, formats, and systems have advanced. They will continue to evolve due to the development of new digital media and web-scale initiatives.

Local practices, including the categories and levels of cataloging adopted by the library, determine departmental configurations and workflows. Established norms, library size, budgets, collections, and services offered impact variations among institutions.

Large law libraries may employ librarians trained to catalog legal works from scratch, i.e., original cataloging with full-level cataloging. These libraries may choose to join one or more of the four Library of Congress’ Programs for Cooperative Cataloging (PCC) and contribute source records to libraries worldwide.

Hybrid cataloging configurations are typical in small and medium-sized law libraries, using original and copy-cataloging techniques for some items and purchasing vendor-supplied records for others. Copy-catalogers may freely download existing source records from the Library of Congress Catalog or pay a nominal fee to download them from a bibliographic utility, such as OCLC. A staff member generally verifies the accuracy of the record structure and content and then makes edits as prescribed by local cataloging policies. Law library local policies often require catalogers to customize records to meet the legal community’s research needs. Examples of customizing local records include:

- Adding a title entry, not present on the piece in hand, to identify a publication by a well-known popular name

- Adding a name entry to recognize faculty members authoring a chapter

- Adding a note about titles updated by pocket parts

Staff members in small to medium-sized law libraries will perform much more copy cataloging than original cataloging. Some libraries may choose to use copy-cataloging techniques and elect to outsource parts or the entire cataloging process to a third party. The vendors perform the necessary cataloging and physical processing of the books before shipping them to the library. Some law libraries reside within a university or college system and receive cataloging support under the auspices of the main campus library.

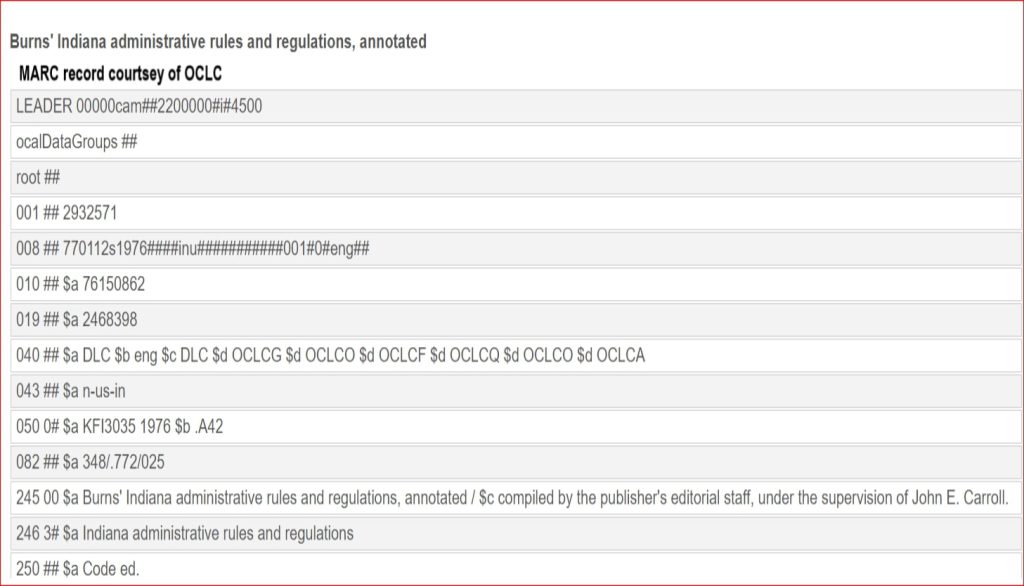

CONCEPT IN ACTION: CUSTOMIZING METADATA FOR FINDABILITY

The Law Library received an electronic copy of “Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties,” edited by Charles J. Kappler. As the catalog librarian inspects the vendor-supplied MARC record, he realizes that although there is an appropriate title field (245) in the MARC record, it does not contain the title recognized by members of the law school community, “The Kappler Report.” To increase search precision and discoverability, the cataloger adds this title into an alternate MARC field (246). The electronic title now surfaces when the law community searches for “The Kappler Report.”

Vendor-supplied bibliographic records are sometimes brief records that provide minimal access. Purchasing or downloading free vendor records is advisable when providing access to electronic titles, meeting work deadlines, or when a lack of staff or technological issues arise. Vendors for digital law record collections include Cassidy Cataloging, EBSCO, Ex Libris, Gale, Bloomberg BNA, and OCLC via WorldShare Collection Manager. The Vendor-Supplied Records Advisory Working Group (VRAG) of the American Association of Law Libraries, Technical Services Special Interest Section (TS-SIS), reviews and evaluates vendor-supplied law-related cataloging records regularly. VRAG reports are freely available on the TS-SIS web.

Cataloging Standards

Libraries make foundational decisions about the cataloging system and the data entered into it. Adopting and adhering to existing national standards is advisable. Altering widely accepted principles may impede future opportunities to enhance services stemming from the database structure, arrangement, or content. Failing to follow established rules and practice could become problematic in future circumstances when libraries migrate to newer systems or join other libraries to form consortiums with combined catalogs that offer a more extensive selection of titles to their communities.

Catalogers create surrogate records to enhance the information seeker’s experience. Descriptive and subject cataloging are the two categories of effort that make up the cataloging process. Each function requires associated standards and tools.

Descriptive cataloging describes the physical aspects of a work, such as the number of pages and size, and identifies access points, such as author, title, series title, subject, and publisher. Resource Description and Access (RDA) is the current international cataloging code that guides information professionals in applying the correct principles in the creation of bibliographic records. RDA incorporates much of the former codes, Anglo-American Cataloging Rules (AACR and AACR2), and operates with other internationally accepted standards, such as IFLA’s International Standard of Bibliographic Description (ISBD) and Machine-Readable Cataloging (MARC). The standard supports the advancement of Library Service Platforms in an attempt to improve access to bibliographic metadata. Unlike its predecessors, RDA accommodates the cataloging of both traditional and digital resources, including updating websites and resources, making this the first code that satisfies the law catalogers’ unique requirements for describing continuously updated materials such as loose-leaf publications. Before implementing RDA, law catalogers frequently referred to supplemental publications to overcome the obstacles presented in cataloging updating loose-leaf publications and primary legal materials.ii

Subject cataloging requires the cataloger to analyze the work in hand or on-screen to determine the subject matter and call number. Most law libraries rely on the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) as the source for authorized subject headings, i.e., controlled vocabulary. The cataloger consults the LCSH to decide the precise word or words that best describe the most significant attributes represented in a work. Adding the preferred term or terms to the bibliographic record creates an added entry that enhances the search and retrieval process.

Authority control, i.e., access point control, is an essential aspect of cataloging that maintains consistent and correct forms for names, subjects, and uniform titles by disambiguating items with similar or identical headings. The Library of Congress Authorities is available free of charge. Libraries often outsource the authority control work and receive regular updates. Companies offering authority services include Backstage Library Works and MARCIVE, Inc.

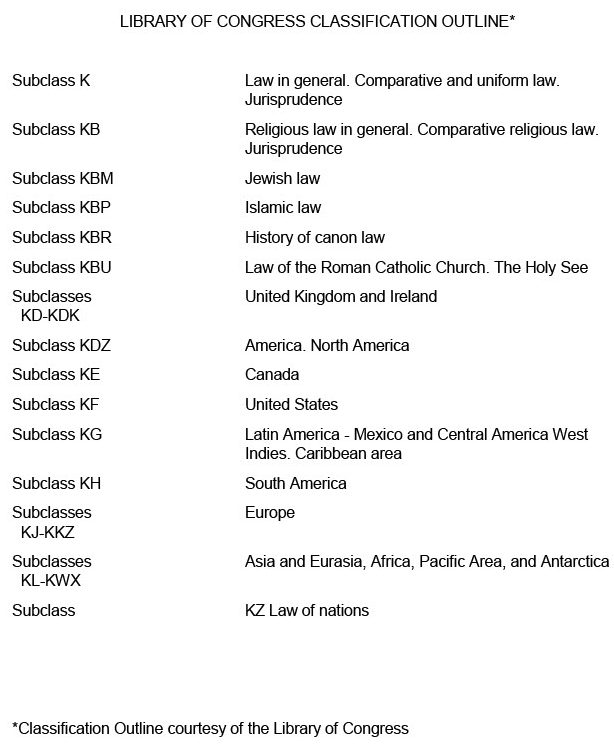

The cataloger assigns an LC call number derived from the dominant subject heading using the Library of Congress Classification system (LCC). The LCC uses a single letter to identify each primary class and two or three letters to identify subclasses. There are twenty-one basic classes, and most contain subclasses. The class that represents the subject of law is Class K. The K class includes 25 subclasses. For example, class K, Law has subclasses K1-7720, Law in general; KF, Federal law of the United States; KFA-KFZ, individual state laws; KZ, Law of nations; KZA, Law of the sea; KZD, Space law, law of outer space.

Encoding Standards

The digital structure that allows computers to store, exchange, use, and interpret library data is Machine-Readable Cataloging (MARC). LC first developed MARC in the 1960s to automate the printing of cards for a physical card catalog. The Network Development and MARC Standards Office at LC continues to maintain and update MARC. The MARC formats contain tags, indicators, subfields, and coded values to identify data elements.

While catalogers finally have standards that allow for creating and maintaining data for online resources, MARC is limited in the ability to interconnect with the web. In 2011, the Network Development and MARC Standards Office of the Library of Congress began investigating a new model, Bibliographic Framework (BIBFRAME), to provide a foundation for the future of bibliographic description. The initiative is underway to translate MARC data into linked data that will allow connecting the library catalog to the semantic web and a linked-data environment.iii

Tools

Cataloging and authority control documentation is available online, free of charge, from the Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Directorate at the LC website. Arranged by topic, the page provides resources and standards for library and information service communities. Here one can download call number schedules, subject headings, manuals, and many more tools.iv

Enhanced products provided by LC are subscription-based. Classification Web is a tool that assists the cataloger in assigning call numbers and subject headings, among other related functions. Cataloger’s Desktop includes manuals, lists, and formats essential to the work of cataloging. Access to Classification Web and the RDA Toolkit through the Cataloger’s Desktop is possible, but separate subscriptions are required. The American Library Association manages the subscription and access to The RDA Toolkit.

Library Service Platforms

Libraries rely on specially designed systems to manage data and processes from all functional areas. Modules interchange data among the areas of acquisitions, cataloging, circulation, course reserves, and serials. Staff view and manage data from the administrative module. At the same time, researchers discover and display holdings and status information on the Online Public Access Catalog (OPAC). Many law libraries with dense continuation collections adopted a legacy system early on developed by Innovative Interfaces, Incorporated (III or Triple I), with expanded capabilities in managing print serial titles and collections.

Integrated Library Systems (ILS) have advanced following web technologies and changing data concepts. With many still in operation today, systems of yesteryear enhance the discoverability of resources located within a brick and mortar establishment. Until the last few years, computer servers containing the software and data resided within the library building. The previous generation of library systems requires the purchase, installation, and integration of an assortment of components to accommodate electronic resources’ inclusion.

Contemporary systems, Library Service Platforms (LSP), are replacing the former generation of Integrated Library Systems (ILS). LSPs continue to offer the traditional functional options, in addition to systematically managing and accessing electronic resources. Newer platforms accommodate a variety of collection types, including online and physical-digital items. Providers now offer state-of-the-art hosted Software as a Service (SaaS) in the cloud. The ability to find full-text digital information is now paramount. Systems often include a knowledge base along with an Open URL resolver that permits the discovery of full-text data. The optimal knowledge base includes human-indexed subject fields that increase precision in searches. With expanded search capabilities, the discovery interface resembles the Google one-search box.

The LSP market is shrinking, and libraries are moving away from legacy systems to contemporary models. Currently, three proprietary companies offer systems of interest to academic law libraries: ExLibris, OCLC, and SirsiDynix. Although the architectures are monolithic, these systems provide robust Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) that allow dynamic interoperability between systems. APIs can be used to authenticate library users, integrate the LSP and e-book lending platforms, and connect the LSP to learning management systems.

Open-source systems are an option. Developers can freely download, use, and modify programming codes and create highly customizable systems. However, the cost incurred is in implementing, training, updating, and problem-solving. FOLIO, a new open-source option, is now available with support options. The system is the first of a kind that uses a microservices architecture containing modular units that perform specific functions, which increases flexibility when updates or changes are required.v

Electronic Resources

The Growth of Electronic Resources

The legal research field was ahead of its time in the 1950s and 60s, pioneering electronic systems to help researchers search court opinions. These systems, such as LEXIS terminals, entered law schools in the 1970s. Nevertheless, electronic resources made minimal impact on law library technical services for decades. Print resources were less expensive, and patrons continued to prefer using print for their research. As broadband and Wi-Fi replaced dial-up connections in the early 2000s, electronic resources became nimbler and more user-friendly and began to proliferate. By the 2010s, the price gap between print and electronic narrowed, librarians acknowledged the ease of automatic updates, and patrons preferred the convenience of online access. These factors led libraries to shift toward purchasing more electronic subscriptions and canceling large quantities of print materials. On average, librarians have also become more comfortable with the stability and archival value of electronic resources.

Effect on Law Library Technical Services

The shift to electronic resources has had a dramatic effect on law library technical services:

- Staff now spend significantly less time maintaining print collections. Law libraries have traditionally spent much more time updating print collections than other libraries. The transition to electronic has hit law libraries particularly hard, resulting in shrinking staffs and reconfigurations of job duties.

- Electronic resources require frequent troubleshooting to maintain functionality.

- Evolving technology, publisher changes, and patron needs mean that technical services librarians must continuously update their skills.

Management of electronic resources may be handled by a technical services librarian, a public services librarian, or a librarian who is part of both departments.

Major Vendors & Platforms

The following vendors and platforms (in parentheses) are common in law libraries:

- Bloomberg Industry Group (Bloomberg Law)

- RELX Group (Lexis Advance, LexisNexis Digital Library) (Nexis Uni, a simplified legal research system, is subscribed to by many general academic libraries)

- Thomson Reuters (Westlaw, ProView, Checkpoint)

- William S. Hein & Co. (HeinOnline)

- Wolters Kluwer (Cheetah)

Other vendors that are not specific to law but include many law-focused digital offerings popular in academic law libraries include:

- ProQuest (Congressional Insight, Supreme Court Insight, Regulatory Insight, other historical content)

- Gale (The Making of Modern Law series, other historical content)

- Brill (encyclopedias, historical content)

Licensing & Purchasing

The acquisition of electronic resources is more complex than the acquisition of print. Most electronic resources are licensed, meaning access to the resource is rented for a period of time, usually one year. License agreements define who can access the resource and how. License agreements can vary substantially in length and complexity.

Electronic resources can also be purchased. The library pays a larger one-time fee for perpetual access instead of a smaller annual fee. Purchased resources are almost always accessed via the vendor’s website, like a licensed resource. Some vendors charge an annual continuing service fee (CSF) for the use of their platform. The vendor may cap the fee at a maximum amount to reward libraries that purchase a lot of content.

CONCEPT IN ACTION: LICENSING NEW COLLECTIONS

The law library purchased a digital collection of historical documents from an academic vendor a few years ago. The library has some extra money at the end of its fiscal year and wants to purchase another historical collection to support research. The library negotiates with the vendor and receives a volume discount for purchasing two collections together. The vendor waives the annual hosting fee for access to the collection through the vendor’s website because the law library already pays an annual fee to access its prior purchase. A faculty member who learns about the new purchase wants to use the documents’ text for a data mining project. The library signs an additional agreement and pays another, smaller fee to the vendor for an FTP of the content. The library downloads the content for storage on its server and provides the faculty member with access.

Libraries can store purchased content independently of the vendor. Some purchase agreements and vendors provide hard drives containing the content or the ability to download via file transfer protocol (FTP), often with an additional fee. Other vendors allow libraries to store the content but do not provide a download mechanism. Law libraries rarely store such content but may acquire some content for faculty data analysis projects (additional permissions may be required).

Negotiation

Librarians responsible for contracts with vendors should always consider negotiating for a more favorable agreement, keeping the following principles in mind:

- Price. Like print resources, electronic resources increase in cost much faster than law library budgets, usually at 3% to 10% annually. These increases are not sustainable. Always consider trying to negotiate a lower price or walking away.

- Campus-wide and walk-in patron access. Law libraries that are part of a larger university campus or that permit access by public patrons (or both), including attorneys and pro se litigants, should always consider asking for access for those patrons. This option does not exist for single sign-on resources but is available for IP-authenticated resources. Some vendors offer licenses for patron-access terminals—designated computer stations that walk-in patrons can use—but they are costly.

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL). Be clear on whether the license allows for sharing via ILL.

- Clarity. If you do not understand something in the contract, ask the vendor what it means. Request that confusing or unclear provisions be rewritten.

Electronic Resource Management (ERM), Knowledge Bases, & Link Resolvers

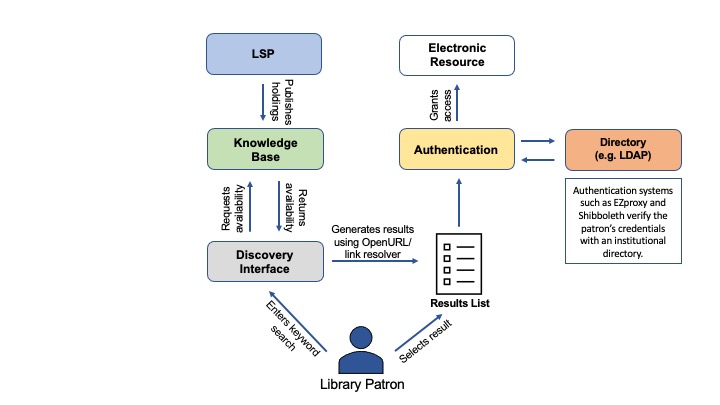

Tracking an electronic resource through its life cycle requires recording information about trial access, subscription dates and renewals, authentication, link resolvers, access to user statistics, and other license terms. An Electronic Resource Management (ERM) system does all this—organizing vendor contacts, license terms, acquisitions, and additional information in one place. Some commercial systems, such as the Alma/Primo system from Ex Libris, integrate an ERM with a knowledge base and link resolver. A knowledge base is similar to an ERM, containing a list of electronic resources the library subscribes to with metadata, including coverage dates. When a patron’s search using the discovery interface locates an electronic resource, the link resolver pulls metadata from the knowledge base to create a link to the resource.

Many academic law libraries utilize the main campus LSP. Libraries that cannot afford a commercial ERM can consider using the free open source ERM CORAL, building a custom database, or using a spreadsheet. These options may be free or low cost but can require significant investments of time and expertise, and spreadsheets are unwieldy for libraries with many resources to manage.

Authentication & Establishing Access

Many electronic resources in law libraries use single sign-on to authenticate users, which is easy to set up. Patrons are given a registration code and a link to a website where they use the code to create an individual account with a username and password. Lexis, Westlaw, CALI, Casetext, and Bloomberg Law use this type of authentication. Often the librarian who oversees electronic resources will distribute these codes.

Other resources are authenticated via IP address. Vendors “whitelist” a range of IP addresses, meaning the vendor’s website grants access to any device accessing it within the permitted IP range. IP authentication is used for many electronic resources, including HeinOnline, Gale products (including Making of Modern Law), ProQuest products, JSTOR, and Fastcase. Setting up IP access is generally straightforward; the library simply provides the vendor with its IP range. Establishing access to IP-authenticated resources for researchers outside the permitted IP range (or off-campus) can be more challenging. Many law libraries use a virtual private network (VPN) or EZproxy from OCLC to establish off-campus access for patrons. EZproxy acts as an intermediary between the patron and the electronic resource. EZproxy makes a request “by proxy” to the resource on behalf of the off-campus patron. The patron receives access because the request appears to come from within the permitted IP range. Patrons verify their identity with the EZproxy server by entering their institutional credentials. The EZproxy server matches the requested electronic resource with its list of configured directives, called stanzas. If EZproxy locates the requested electronic resource in a stanza, it grants access.

Another option is creating a single sign-on for all electronic library resources using a SAML system like OpenAthens or Shibboleth. Setting up these systems may require more time and money than a law library can afford on its own.

E-books

Law libraries have been a bit slower in adopting the e-book format than other libraries but are catching up. Many legal publishers have developed proprietary platforms (e.g., Westlaw’s Proview) or partnered with other platforms (LexisNexis with Overdrive) for their e-books. These platforms can be accessed through a web browser and do not require patrons to download additional software or purchase an e-reader device. However, legal e-book vendors often offer free apps and e-reader compatibility.

Troubleshooting

Access to electronic resources breaks down with surprising frequency. All law libraries should proactively check functionality and establish procedures for handling problems when notified by patrons. Law libraries with small staffs may be tempted to forgo creating documentation when solving access problems. Nevertheless, documentation is essential to identify consistent issues that could be solved more systematically, aid in resource evaluation, provide product feedback, and develop institutional memory.

Tools that can be used to document troubleshooting efforts include spreadsheets, Google Forms, and Kanban boards like Trello. The electronic resources librarian should maintain a list of common issues and a procedure or flowchart for troubleshooting. Common problems include:

- Incorrect URLs generated by knowledge bases and link resolvers due to metadata parsing issues;

- Vendor platform changes, causing updates to be required for URLs and/or database stanzas in EZproxy;

- Patrons using outdated, bookmarked URLs;

- Incorrect or missing patron profiles in the authentication system;

- Browser cookies or plug-ins interfering with authentication;

- Unrenewed licenses, or unpaid or uncredited invoices;

- Changes to IP ranges.

CONCEPT IN ACTION: HANDLING E-RESOURCE ACCESS ISSUES

Kira, a 3L, notifies the reference desk that she cannot access an e-book. Her email is forwarded to Jeremiah, the electronic resources librarian. Jeremiah quickly verifies that access is working using both the vendor’s website in the A-Z List and the e-book URL generated by the law library discovery interface. He asks Kira 1) where she found the e-book, 2) where she was when she tried to access it, and 3) the error message she received. Kira responds that she found the e-book on the main campus library website while researching in her apartment. The error message was “not configured for access.” Jeremiah determines that while the law library has added the stanza for the vendor’s website—a new subscription—to its separate EZproxy server, the main campus library has not. Jeremiah directs Kira to the law library’s A-Z list for immediate access and asks the main campus library to add the stanza to its EZproxy config file.

Usage Data

Usage data for collection evaluation is one of the benefits of providing electronic resources. Academic publishers generally provide COUNTER-compliant usage reports as standard practice and use the SUSHI protocol so libraries can automate the gathering of reports. COUNTER reports, designed primarily to track searches and usage of journal articles, do not translate as well to legal materials. Many legal publishers do not yet provide COUNTER-compliant reports or even any usage information, and law librarians may still resort to manual methods to collect some data. Some vendors offer administrative portals where librarians can manage access and run usage reports, while others will provide customized reports on request or monthly reports via email. Law librarians can also obtain usage data from the LSP and authentication systems like OpenAthens and EZproxy.

Discovery

The law library’s discovery interface provides an access point for patrons with an enhanced search of MARC records in the library’s LSP. Libraries can add records for a database or collection (e.g., a record for Making of Modern Law: Trials, 1600-1926) as well as records for titles contained within the database (e.g., a record for “The Tryal of John Barbot, Attorney at Law, for the Murder of Mathew Mills, Esq.”). Discovery interfaces can also search directly within electronic databases of vendors that support federated searching. Law librarians can further facilitate access to electronic resources by curating a list of subscriptions and free electronic resources using tools like Springshare’s LibGuides A-Z Database List, including resources from the main campus library that law patrons may not find if the law library uses a separate discovery interface. Librarians can reuse entries in the A-Z List on topical research guides created within LibGuides.

Conclusion

As the amount of legal information in the world continues to increase, the need for high-quality acquisition, cataloging, and access services for print and electronic resources continues to grow. Technical services processes are becoming increasingly more technical as the information management field advances. New law librarians, including public service law librarians, must develop an understanding of technical services processes to provide patrons with meaningful access to legal information.

- Balloffet, Nelly and Jenny Hille. Preservation and Conservation for Libraries and Archives. Chicago: American Library Association, 2005.

- Breeding, Marshall. “What is ERM? Electronic Resource Management Strategies in Academic Libraries.” Computers in Libraries 38, no. 3 (2018): 17-21. http://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/apr18/Breeding–What-is-ERM.shtml.

- Lembke, Melody Busse, and Melissa Beck. Cataloging Legal Literature. AALL Publications Series; Number 22. 5th edition, Getzville, New York: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 2020.

- Library of Congress, Overview of Bibliographic Framework Initiative https://www.loc.gov/bibframe/.

- Randtke, Wilhelmina and Stacy Fowler. “The Current State of E-books in U.S. Law Libraries: A Survey.” Law Library Journal 108, no. 3 (2016): 361-381.

- Technical Services Law Librarian (TSLL), published quarterly, is the official publication of the Technical Services Special Interest Section and the Online Bibliographic Services Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries.