16.2 Grief and the Grieving Process

Terri J. Farmer, PhD, PMHNP, CNE

Caring for those who are dying and those who have suffered loss is an integral part of nursing. As a profession, we are accustomed to using advanced technology and resources to support life and combat dying. When a patient dies, it may seem like a failure of healthcare interventions. Yet we all will die. Knowledge to care for those at the end of life and for the people who love them is essential in any healthcare setting. Historically, most people died at home surrounded by family. Today, many more deaths occur in hospitals and extended care facilities. In the 1960s, the first hospices were established, which paved the way for Improving care during the dying processes and building a body of knowledge to guide nurses. Now, many options are available for patient-centered end of life care, including support for those who die at home.

Important Concepts

Three major concepts associated with grieving are loss, grief, and mourning. Loss is the absence of a possession or future possession with the response of grief and the expression of mourning. The feeling of loss can be associated with the loss of health, changes in relationships and roles, and eventually the loss of life. After a patient dies, the family members and other survivors experience loss.[1]

Grief is the emotional response to a loss, defined as the individualized and personalized feelings and responses that an individual makes to real, perceived, or anticipated loss. These feelings may include anger, frustration, loneliness, sadness, guilt, regret, and peace. Grief affects survivors physically, psychologically, socially, and spiritually. The grief process is not orderly and predictable. Emotional fluctuation is normal and expected. There are times when the person experiencing the loss feels in control and accepting, and there are other times when the loss feels unbearable, and they feel out of control[2]. See Figure 17.1[3] for an image of an individual in a cemetery who may be experiencing grief.

Mourning is the outward, social expression of loss. Individuals outwardly express loss based on their cultural norms, customs, and practices, including rituals and traditions. Some cultures may be very emotional and verbal in their expression of loss, such as wailing or crying loudly. Other cultures are stoic and show very little reaction to loss. Culture also dictates how long one mourns and how the mourners “should” act. The expression of loss is also affected by an individual’s personality and previous life experiences.[3]

Types of Grief

People grieve at different times and in different ways. The circumstances around the death greatly influence the grieving process. Below are general types of grief, but nurses recognize that each individual has their own process.

Anticipatory Grief

Anticipatory grief is defined as grief before a loss, associated with diagnosis of an acute, chronic, and/or terminal illness experienced by the patient, family, or caregivers. Examples of anticipatory grief include actual or fear of potential loss of health, independence, body part, financial stability, choice, or mental function.[4]

Sometimes anticipatory grief starts at the time of a terminal diagnosis and can proceed until the person dies. Both patients and their family members can feel anticipatory loss. The patient often anticipates the loss of independence, function, or comfort, which can cause significant pain and anxiety if not given the proper support. A patient may also have concrete fears such as the loss of the ability to drive, live independently, or maintain their current body image. They may also have grief regarding the loss of anticipated family experiences, such as celebrating the marriage of a child, the birth of a grandchild, an anniversary, or another significant life event. The family often starts grieving for the loss of their loved one before they die as they envision their life without their loved one in it. This type of grief has been shown to help cushion a person’s bereavement reaction.[5]

Acute Grief

Acute grief begins immediately after the death of a loved one and includes the separation response and response to stress. During this period of acute grief, the bereaved person may be confused and/or uncertain about their identity or social role. They may disengage from their usual activities and experience disbelief and shock that their loved one is gone.[6] See Figure 16.2b[7] for an image of a sculpture depicting acute grief.

Acute grief includes the common feelings, behaviors, and reactions to loss. Normal grief reactions can include the following:

- Physical symptoms such as hollowness in the stomach, tightness in the chest, weakness, heart palpitations, sensitivity to noise, breathlessness, tension, lack of energy, and dry mouth

- Emotional symptoms such as numbness, sadness, fear, anger, shame, loneliness, relief, emancipation, yearning, anxiety, guilt, self-reproach, helplessness, and abandonment

- Cognitive symptoms such as a state of depersonalization, confusion, inability to concentrate, dreams of the deceased, idealization of the deceased, or a sense of presence of the deceased

- Behavioral signs such as impaired work performance, crying, withdrawal, reactivity, changed relationships, or avoidance of reminders of the deceased[8]

Acute grieving may take months and but can also take years, depending on the loss. No one ever truly gets over the loss, but there is an eventual reconnection with the world of the living as the relationship with the deceased changes.[9]

Disenfranchised Grief

Disenfranchised grief is grief over any loss that is not validated or recognized. Those affected by this type of grief do not feel the freedom to openly acknowledge their grief. Individuals at risk for disenfranchised grief are those who have lost loved ones to stigmatized illnesses, such as AIDS, or circumstances, such as death while committing a crime. Mothers and/or fathers may grieve over terminated pregnancies or stillborn babies. The loss of someone from a previously severed relationship, divorce, or socially unsanctioned relationship can contribute to this type of grief because the individual may not be able to mourn openly due to the circumstances surrounding the relationship.

Complicated Grief

Complicated grief occurs when there is interference in the grieving process leading to a prolonged, more intense grieving. There is often preoccupation with the circumstances of the loss, which may manifest as feelings of guilt regarding the situation around the loss. There is generally a negative focus on the loss, which overrides any positive emotions the person may feel. Complicated grieving can cause significant distress, impaired functioning, and suicidal thinking.[10] Complicated grief is seen in 10-20% of individuals experiencing the death of a romantic partner and with higher estimates for parents who have lost a child. According to the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC), there are four types of complicated grief, including chronic grief, delayed grief, exaggerated grief, and masked grief. Risk factors for developing complicated grief include sudden or traumatic death, suicide, homicide, a dependent relationship with the deceased, chronic illness, death of a child, multiple losses, unresolved grief from prior losses, concurrent stressors, witnessing a difficult dying process such as pain and suffering, lack of support systems, and lack of a faith system. Complicated grief may require professional assistance depending on its severity. Factors that contribute to complicated grief in older adults include lack of a support network, concurrent losses, poor coping skills, and loneliness.[11]

- Chronic Grief: Normal grief reactions that do not subside and continue over very long periods of time.

- Delayed Grief: Normal grief reactions that are suppressed or postponed by the survivor consciously or unconsciously to avoid the pain of the loss.

- Exaggerated Grief: An intense reaction to grief that may include nightmares, delinquent behaviors, phobias, and thoughts of suicide.

- Masked Grief: Grief that occurs when the survivor is not aware of behaviors that interfere with normal functioning as a result of the loss. For example, an individual cancels lunch with friends so they can go to the cemetery daily to visit their loved one’s grave.[12]

A discussion of grief would be incomplete without acknowledging the public grief that occurs with tragedies such as war, natural disasters, mass shootings, and pandemics. Continual access to news information and visual images can lead to symptoms of shock and grief.

Stages of Grief

There are several stages of grief that may occur following a loss. It can be helpful for nurses to have an understanding of these stages to recognize the emotional reactions as symptoms of grief so they can support patients and families as they cope with loss. Famed Swiss psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler-Ross identified five main stages of grief in her book On Death and Dying.[13] Patients and families may experience these stages along a continuum, move randomly and repeatedly from stage to stage, or skip stages altogether. There is no one correct way to grieve, and an individual’s specific needs and feelings must remain central to care planning. It is more important to understand that these emotions and behaviors are common and expected.

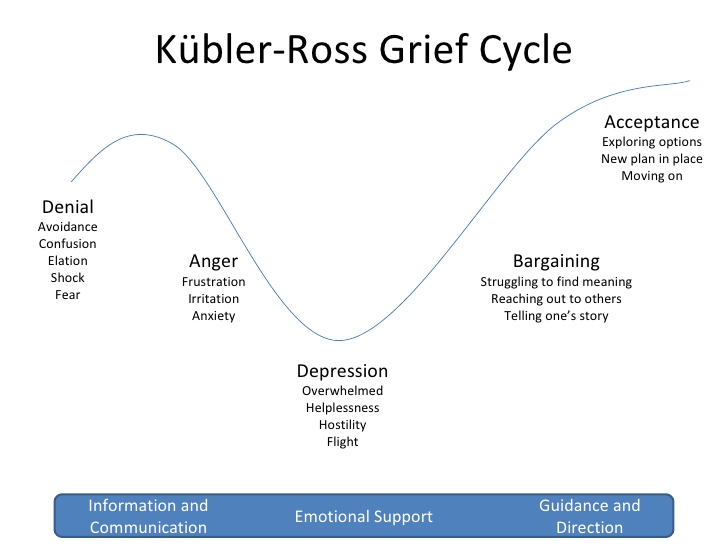

Kuber-Ross identified that patients and families demonstrate various characteristic responses to grief and loss. These stages include denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance, commonly referred to by the mnemonic “DABDA.” See Figure 16.2c[14] for an illustration of the Kubler-Ross Grief Cycle. Keep in mind that these stages of grief not only occur due to loss of life, but also occur due to significant life changes such as divorce, loss of friendships, loss of a job, or diagnosis with a chronic or terminal illness.[16]

View the beginning of this YouTube video clip from the movie Steel Magnolias[15] that shows elements of the grieving process.

Denial

Denial occurs when the individual refuses to acknowledge the loss or pretends it isn’t happening. The feeling of denial is self-protective as an individual attempts to numb overwhelming emotions as they process the information. The denial process can help to offset the immediate shock of a loss. Denial is commonly experienced during traumatic or sudden loss or if unexpected life-changing information or events occur. For example, a patient who presents to the physician for a severe headache and receives a diagnosis of terminal brain cancer may experience feelings of denial. See Figure 16.2d[16] for an image of a person depicting reaction to unexpected news with denial.

Anger

Anger in the grief process often masks pain and sadness. The subject of anger can be quite variable; anger can be directed to the individual who was lost, internalized to self, or projected toward others, such as family members. Additionally, an individual may lash out at those uninvolved with the situation or have bursts of anger that seemingly have no apparent cause. Health care professionals should be aware that anger may often be directed at them as they provide information or provide care. It is important that health care team members, family members, and others who become the target of anger recognize that the anger and emotion are not a personal attack, but rather a manifestation of the challenging emotions that are a part of the grief process. If possible, the nurse can provide supportive presence and allow the patient or family member time to vent their anger and frustration while still maintaining boundaries for respectful discussion. Rather than focusing on what to say or not to say, allowing a safe place for a patient or family member to verbalize their frustration, sorrow, and anger can offer great support. See Figure 16.2e[17] for an image of a child depicting anger.

Bargaining

Bargaining can occur during the grief process in an attempt to regain control of the loss. When individuals enter this phase, they are looking to find ways to change or negotiate the outcome by making a deal. Some may try to make a deal with a higher power to take away their pain or to change their reality by making promises to do better or give more of themselves if only the circumstances were different. For example, a patient might say, “I promised God I would stop smoking if He would heal my wife’s lung cancer.”

Depression

Feelings of depression can occur with intense sadness over the loss of a loved one or the situation. Depression can cause loss of interest in activities, people, or relationships that previously brought one satisfaction. Additionally, individuals experiencing depression may experience irritability, sleeplessness, and loss of focus. It is not uncommon for individuals in the depression phase to experience significant fatigue and loss of energy. Simple tasks such as getting out of bed, taking a shower, or preparing a meal can feel so overwhelming that individuals simply withdraw from activity. In the depression phase, it can be difficult for individuals to find meaning, and they may struggle with identifying their own sense of personal worth or contribution. Depression can be associated with ineffective coping behaviors, and nurses should watch for signs of self-medicating through the use of alcohol or drugs to mask or numb depressive feelings. See Figure 16.2f[18] for an image of a person whose body language might suggest depressed feelings.

Acceptance

Acceptance refers to an individual understanding the loss and knowing it will be hard but acknowledging the new reality. The acceptance phase does not mean absence of sadness but is the acknowledgement of one’s capabilities in coping with the grief experience. In the acceptance phase, individuals begin to reengage with others, find comfort in new routines, and even experience happiness with life activities again. See Figure 16.2g[19] of an image of a person depicting acceptance.

Grief Tasks

Kubler-Ross’s grief stages describe many feelings that individuals commonly experience while grieving loss. Other experts also describe the grieving process in terms of tasks that one must accomplish. These tasks include notification and shock, experiencing the loss, and reintegration.[20]

- Notification and shock: This phase occurs when a person first learns of the loss and experiences feelings of numbness or shock. The person may isolate themselves from others while processing this information. The first task for the person to complete is to acknowledge the reality of the loss by assessing and recognizing the loss.

- Experiencing the loss: The second task involves experiencing the loss emotionally and cognitively. The person must work through the pain by reacting to, expressing, and experiencing the pain of separation and grief.

- Reintegration: The third task involves reorganization and restructuring of family systems and relationships by adjusting to the environment without the deceased. The person must form a new reality without the deceased and adapt to a new role while also retaining memories of the deceased.[21]

As a nurse, you can greatly assist patients and family members as they move through the grieving process by being willing and committed to spending time with them. Listen to their stories, be present, and bear witness to their pain. Remember that you cannot fix everything, but taking time to assess their symptoms of grief helps you identify other resources for support. Communication will be discussed further later in this section.

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. The Macmillan Company. ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- “WWStoryRome.jpg” by Carptrash is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Shear, M. K. (2012). Grief and mourning gone awry: Pathway and course of complicated grief. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(2), 119-28. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/mshear. ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2015). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “Kubler-ross-grief-cycle-1-728.jpg” by U3173699 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Movieclips. (2014, February 5). Steel Magnolias (8/8) movie CLIP - I wanna know why (1989) HD [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/iZx1W6cHw-g ↵

- “Young-indian-with-disgusting-expression-showing-denial-with-hands-42509-pixahive.jpg” by Sukhjinder is licensed under CC0 ↵

- “Child%27s_Angry_Face.jpg” by Babyaimeesmom is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- “Depressed_(4649749639).jpg” by Sander van der Wel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 ↵

- “Contentment_at_its_best.jpg” by Neha Bhamburdekar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Lowey, S. E. (2015). Nursing care at the end of life. Open Library. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/nursingcare ↵

- Huberman, A. (2022). The science & process of healing from grief. YouTube. https://youtu.be/dzOvi0Aa2EA?si=BdQiY2tfMoW4VsYN ↵

The absence of a possession/person or future possession with the response of grief.

An emotional response to loss including feelings of loneliness, sadness, guilt, regret, anger, and peace that affects survivors physically, psychologically, socially, and spiritually.

The outward expression of loss based on cultural norms, customs, and practices.

Grief before a loss, associated with diagnosis of an acute, chronic, and/or terminal illness experienced by the client, family, or caregivers.

Grief that begins immediately after the death of a loved one and includes the separation response and response to stress.

Grief over any loss that is not validated or recognized. Those affected by this type of grief do not feel the freedom to openly acknowledge their grief.

When interference in the grieving process occurs, leading to a prolonged, more intense grieving. There is often preoccupation with the circumstances of the loss, which may manifest as feelings of guilt regarding the situation around the loss.