17.2 Overview of Disordered Cognition

Terri J. Farmer, PhD, PMHNP, CNE

Cognitive impairment is generally thought of as a condition that affects adults. Children can have cognitive problems and, unlike decline or dementia in adults, cognitive functioning impairments in children are mostly congenital.

Cognitive Impairments in Children

Cognitive impairments in children range from mild impairment in very specific areas to profound intellectual impairments leading to minimal independent functioning. Cognitive impairment is a term used to describe impairment in mental processes that drive how an individual understands and acts in the world, affecting the acquisition of information and knowledge. The following areas are domains of cognitive functioning:

- Attention

- Decision-making

- General knowledge

- Judgment

- Language

- Memory

- Perception

- Planning

- Reasoning

- Visuospatial[1]

Intellectual disability is a diagnostic term that describes intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits identified during the developmental period. In the United States, the developmental period refers to the span of time before 18 years. Children with intellectual disabilities may demonstrate a delay in developmental milestones (e.g., sitting, speaking, walking) or demonstrate mild cognitive impairments that may not be identified until school age. Intellectual disability is typically nonprogressive and lifelong. It is diagnosed by multidisciplinary clinical assessments and standardized testing and is treated with a multidisciplinary treatment plan that maximizes quality of life.[2] The goals of treatment are largely related to building skills to function more comfortably at home or in educational settings. Children and adolescents are not hospitalized for intellectual disabilities but may be admitted for illnesses or surgeries like other children. Intellectual disabilities and implications for care are discussed in Chapter 12.2. See Figure 17.2a for a Special Olympics event.[3]

Cognitive Impairments in Adults and Older Adults

Although there are adults who have intellectual disabilities, cognitive impairments that necessitate health care are generally related to several physical changes that occur in the brain due to aging, traumatic brain injuries, cerebrovascular incidents, neurological disorders, and post-infectious disorders. The structure of neurons changes, including a decreased number and length of dendrites, loss of dendritic spines, a decrease in the number of axons, an increase in axons with segmental demyelination, and a significant loss of synapses. These physical changes occur in older adults experiencing cognitive impairments, as well as in those who do not.[4]

It is a common myth that all individuals experience cognitive impairments as they age. Many people are afraid of growing older because they fear becoming forgetful, confused, and incapable of managing their daily life leading to incorrect perceptions and ageism. Ageism refers to stereotyping older individuals because of their age. Losing language skills, becoming unable to make decisions appropriately, and being disoriented to self or surroundings are not normal aging changes.

Dementia, Delirium, and Depression

If cognitive changes in adults occur, a complete assessment is required to determine the underlying cause of the change and if that cause is an acute or chronic condition. For example, dementia is a chronic condition that affects cognition whereas depression and delirium can cause acute confusion with a similar clinical appearance to dementia. Differentiating among the clinical manifestations has a direct link to the type of care and treatment.

Dementia

Dementia is a chronic condition of impaired cognition caused by brain disease or injury and marked by personality changes, memory deficits, and impaired reasoning. Dementia can be caused by a group of conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), vascular dementia, frontal-temporal dementia, and Lewy body disease. Clinical manifestations of dementia include forgetfulness, impaired social skills, and impaired decision-making and thinking abilities that interfere with daily living. Dementia is gradual, progressive, and irreversible.[5] Although dementia is not reversible, appropriate assessment and nursing care improve the safety and quality of life for those affected by dementia.

As dementia progresses and cognition continues to deteriorate, nursing care must be individualized to meet the needs of the patient and family. Providing patient safety and maintaining quality of life while meeting physical and psychosocial needs are important aspects of nursing care. Unsafe behaviors put individuals with dementia at increased risk for injury. These unsafe or inappropriate behaviors often occur due to the patient having a need or emotion, such as pain, hunger, anxiety, or a need to use the bathroom, without the ability to express it. The patient’s family orcaregivers require education and support to recognize that behaviors are often a symptom of dementia and/or a communication of a need and to help them best meet the needs of their family member.[6]

Delirium

Delirium is an acute state of cognitive impairment that typically occurs suddenly due to a physiological cause, such as infection, hypoxia, electrolyte imbalances, drug effects, or other acute brain injury. Sensory overload, excess stress, and sleep deprivation can also cause delirium. Hospitalized older adults are at increased risk for developing delirium, especially if they have been previously diagnosed with dementia. One-third of patients aged 70 years or older exhibit delirium during their hospitalization. Delirium is the most common surgical complication for older adults, occurring in 15% – 25% of patients after major elective surgery and up to 50% of patients experiencing hip-fracture repair or cardiac surgery.[7]

The symptoms of delirium usually start suddenly, over a few hours or a few days, and they often come and go. Common symptoms include the following:

- Changes in alertness (usually most alert in the morning and less at night)

- Changing levels of consciousness

- Confusion

- Disorganized thinking or talking in a way that does not make sense

- Disrupted sleep patterns or sleepiness

- Emotional changes: anger, agitation, depression, irritability, overexcitement

- Hallucinations and delusions

- Incontinence

- Memory problems, especially with short-term memory

- Trouble concentrating[8]

Delirium and dementia have similar symptoms, so it can be hard to tell them apart. They can also occur together.

Nurses must closely monitor the cognitive function of all patients and promptly report any changes in mental status to the health care provider. The provider will take a medical history, perform physical and neurological examinations, perform mental status testing, and may order diagnostic tests based on the patient’s medical history. After the cause of delirium is determined, treatment is targeted to the cause to reverse the effects.

General interventions to prevent and treat delirium in older adults are as follows:

- Control the environment. Make sure that the room is quiet and well-lit, have clocks or calendars in view to provide time orientation, and encourage family members to visit.

- Ensure a safe environment with the call light within reach and side rails up if indicated.

- Administer prescribed medications, including those that control aggression or agitation, and pain relievers if there is pain.

- Ensure the patient has their glasses, hearing aids, or other assistive devices for communication in place. Lack of assistive sensory devices can worsen delirium.

- Avoid sedatives. Sedatives can worsen delirium.

- Assign the same staff for patient care when possible.[10]

- Get patients up and out of bed when possible

- Control pain with pain relievers (unless the pain medication is causing the delirium)

- Administer prescribed medications to distressed clients at risk to themselves or to others to calm and settle them, such as haloperidol (However, administer medications with caution because oversedation can worsen delirium.)

- Avoid the use of restraints

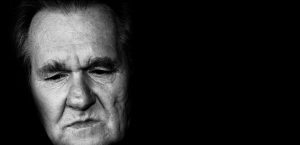

Depression

Depression is a brain disorder with a variety of causes, including genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. It is a commonly untreated condition in older adults and can result in impaired cognition and difficulty making decisions. It is likely to occur in response to major life events involving health and loved ones. Having other chronic health problems, such as diabetes, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, heart disease, and kidney disease, increases the likelihood for depression in older adults and can cause the loss of their ability to maintain independence.[11] See Figure 17.2b[12] for an older adult with depressed affect.

Symptoms of depression include the following:

- Feeling sad or “empty”

- Difficulty with concentration and cognitive tasks

- Loss of interest in favorite activities

- Overeating or not wanting to eat at all

- Not being able to sleep or sleeping too much

- Feeling very tired

- Feeling hopeless, irritable, anxious, or guilty

- Aches, pains, headaches, cramps, or digestive problems

- Thoughts of death or suicide[13]

Depression is treatable with medication and psychotherapy. However, older adults have an increased risk for suicide, with the suicide rates for individuals over age 85 years being the second highest rate overall. Nurses should provide appropriate screening to detect potential signs of depression as an important part of promoting health for older adults.

Comparison of Three Conditions

When an older adult presents with confusion, determining if it is caused by delirium, dementia, depression, or a combination of these conditions can pose many challenges to the health care team. It is helpful to know the patient’s baseline mental status from a family member, caregiver, or previous health care records. If a patient’s baseline mental status is not known, it is an important patient safety consideration to assume that confusion is caused by delirium with a thorough assessment for underlying causes.[14] See Table 17.1 for a comparison of symptoms of dementia, delirium, and depression.

Table 17.1 Comparison of Dementia, Delirium, and Depression[15]

| Dementia | Delirium | Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | Vague, insidious onset; symptoms progress slowly | Sudden onset over hours and days with fluctuations | Onset often associated with identifiable trigger or life event such as bereavement |

| Symptoms | Symptoms may go unnoticed for years. May attempt to hide cognitive problems or may be unaware of them. Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening (referred to as “sundowning”) | Often disoriented to time, place, and person. Impaired short-term memory loss and information processing. Confusion is often worse in the evening | Vague in early stages and often worse in the morning. Can include subjective complaints of memory loss |

| Consciousness | Normal | Impaired attention/alertness | Normal |

| Mental State | Possibly labile mood. Consistently decreased cognitive performance | Emotional lability with anxiety, fear, depression, aggression. Variable cognitive performance | Distressed/unhappy. Variable cognitive performance |

| Delusions/Hallucinations | Common | Common | Rare |

| Psychomotor Disturbance | Psychomotor disturbance in later stages | Psychomotor disturbance present – hyperactive, purposeless, or apathetic | Slowed psychomotor status in severe depression |

- Zeldin, A.S. (2021, November 16). Intellectual disability. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/917629-overview ↵

- Zeldin, A.S. (2021, November 16). Intellectual disability. Medscape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/917629-overview ↵

- “22605761265_9f8e65a7ad_k.jpg” by Special Olympics 2017 is in the Public Domain ↵

- Murman, D. L. (2015). The impact of age on cognition. Seminars in Hearing, 36(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1555115 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). Alzheimer’s & dementia. Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia ↵

- Downing, L. J., Caprio, T. V., & Lyness, J. M. (2013). Geriatric psychiatry review: Differential diagnosis and treatment of the 3 D’s - delirium, dementia, and depression. Current Psychiatry Reports, 15, 365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-013-0365-4 ↵

- Marcantonio, E. R. (2017). Delirium in hospitalized older adults. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(15), 1456–1466. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1605501 ↵

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2023). Delirium. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/delirium.html ↵

- The Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, New York University, Rory Meyers School of Nursing. (n.d.). Assessment tools for best practices of care for older adults. https://hign.org/consultgeri-resources/try-this-series ↵

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2023). Delirium. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/delirium.html ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

- “man-416470_960_720.jpg” by geralt is licensed under CC0 ↵

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. (Updated 2025, March). Depression. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/depression.html ↵

- Marcantonio, E. R. (2017). Delirium in hospitalized older adults. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377(15), 1456–1466. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1605501 ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

A term used to describe impairment in mental processes that drive how an individual understands and acts in the world, affecting the acquisition of information and knowledge.

A diagnostic term that describes intellectual and adaptive functioning deficits identified during the developmental period.

Prejudice or discrimination against people based on their age. Ageism has a negative impact on physical and menatl health.

A group of symptoms that lead to a decline in mental function severe enough to disrupt daily life caused by a group of conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, frontal-temporal dementia, and Lewy body disease.

An onset of an abnormal mental state, often with fluctuating levels of consciousness, disorientation, irritability, and hallucinations.

An episode where the person experiences a depressed mood (feeling sad, irritable, empty) or a loss of pleasure or interest in activities, for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least two weeks.