17.3 Alzheimer’s Disease

Terri J. Farmer, PhD, PMHNP, CNE

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. It is the most common cause of dementia. In most people with AD, symptoms first appear in their mid-60s. One in ten Americans aged 65 years and older has AD.[1]

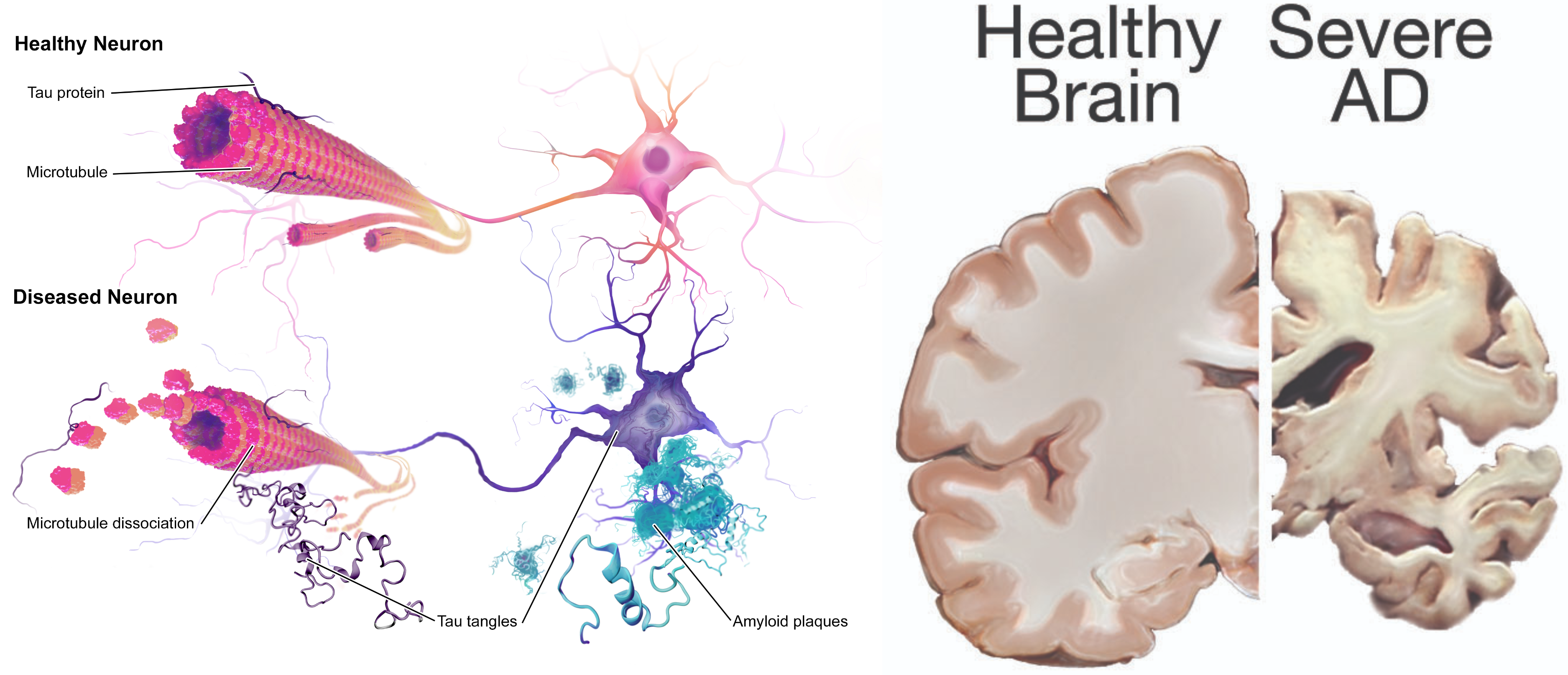

Scientists continue to unravel the complex brain changes involved in the onset and progression of AD. It is thought that changes in the brain may begin a decade or more before memory and other cognitive problems appear. Abnormal deposits of proteins form amyloid plaques and tau tangles throughout the brain. Previously healthy neurons stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and die. The damage initially appears to take place in the hippocampus and cortex, the parts of the brain essential in forming memories. As more neurons die, additional parts of the brain are affected and begin to shrink. By the final stage of AD, damage is widespread, and brain tissue has shrunk significantly.[2] See Figure 17.3a[3] for an image of the changes occurring in the brain during AD.

Figure 17.3a Brain and Neurons Affected by Alzheimer’s Disease

Symptoms of Early Alzheimer’s Disease

There are ten symptoms of early AD[4]:

- Forgetting recently learned information, which disrupts daily life. This includes forgetting important dates or events, asking the same questions over and over, and increasingly needing to rely on memory aids (e.g., reminder notes or electronic devices) or family members for things they used to handle on their own. This is different than a typical age-related change of sometimes forgetting names or appointments but remembering them later.

- Challenges in planning or solving problems. This includes changes in an individual’s ability to develop and follow a plan or work with numbers. For example, they may have trouble following a familiar recipe or keeping track of monthly bills. They may have difficulty concentrating and take much longer to do things than they did before. This is different from a typical age-related change of making occasional errors when managing finances or household bills.

- Difficulty completing familiar tasks. This includes trouble driving to a familiar location, organizing a grocery list, or remembering the rules of a favorite game. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of occasionally needing help to use microwave settings or to record a TV show.

- Confusion with time or place. This includes losing track of dates, seasons, and the passage of time. Individuals may have trouble understanding something if it is not happening immediately. Sometimes they may forget where they are or how they got there. This symptom is different from a typical age-related change of forgetting the date or day of the week but figuring it out later.

- Trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships. Vision problems that include difficulty judging distance or determining color or contrast, or that cause issues with balance or driving can be symptoms of Alzheimer’s. This is different from a typical age-related change of blurred vision related to presbyopia or cataracts.

- New problems with words in speaking or writing. Individuals with Alzheimer’s may have trouble following or joining a conversation. They may stop in the middle of a conversation and have no idea how to continue, or they may repeat themselves. They may struggle with vocabulary, have trouble naming a familiar object, or use the wrong name (e.g., calling a “watch” a “hand-clock”). This is different from a typical age-related change of having trouble finding the right word.

- Misplacing things and losing the ability to retrace steps. A person with AD may put things in unusual places. They may lose things and be unable to go back over their steps to find them again. They may accuse others of stealing, especially as the disease progresses. This is different from a typical age-related change of misplacing things from time to time and retracing steps to find them.

- Decreased or poor judgment. Individuals with Alzheimer’s may experience changes in judgment or decision-making. For example, they may use poor judgment when dealing with money or pay less attention to grooming or keeping themselves clean. This is different from a typical age-related change of making a bad decision or mistake once in a while, like neglecting to change the oil in the car.

- Withdrawal from work or social activities. A person living with AD may experience changes in the ability to hold or follow a conversation. As a result, they may withdraw from hobbies, social activities, or other engagements. They may have trouble keeping up with a favorite team or activity. This is different from a typical age-related change of sometimes feeling uninterested in family or social obligations.

- Changes in mood and personality. Individuals living with Alzheimer’s may experience mood and personality changes. They can become confused, suspicious, depressed, fearful, or anxious. They may be easily upset at home, with friends, or when out of their comfort zone. This is different from a typical age-related change of developing very specific ways of doing things and becoming irritable when a routine is disrupted.

Three Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

There are several stages of AD, referred to as preclinical AD, mild cognitive impairment due to AD, dementia due to mild AD, dementia due to moderate AD, and dementia due to severe AD[5]:

- Preclinical AD: Individuals experience brain changes associated with AD, but symptoms such as memory loss or difficulty thinking are not yet present.

- Mild cognitive impairment due to AD: Individuals have very mild symptoms that do not interfere with everyday activities.

- Dementia due to mild AD: Individuals experience the ten symptoms previously discussed that interfere with some daily activities. They may still be able to drive, work and participate in their favorite activities but often need more time to complete common daily tasks and may require assistance to maximize independence and remain safe. Paying bills and making financial decisions may be especially challenging, which increases their vulnerability to financial scams and financial abuse.

- Dementia due to moderate AD: Individuals experience symptoms that interfere with many daily activities. They often have difficulty completing multistep tasks such as bathing and dressing. They may have episodes of incontinence, begin to have problems recognizing loved ones, and start showing personality and behavioral changes, including suspiciousness and agitation. Behavioral symptoms such as wandering, getting lost, hallucinations, delusions, and repetitive behavior may occur. Clients living at home may engage in risky behavior, such as leaving the house in clothing inappropriate for weather conditions or leaving on the stove burners.[6]

- Dementia due to severe AD: The ability to verbally communicate and walk is greatly diminished, and individuals likely require around-the-clock care with full assistance in washing, dressing, eating, and toileting. They typically spend most of their time in a wheelchair or in bed. This loss of mobility increases their vulnerability to physical complications including blood clots, skin infections and sepsis. Swallowing becomes impaired, increasing their risk for aspiration pneumonia, a common cause of death.[7] See Figure 17.3b[8] for a patient requiring assistance.

There is no single diagnostic test that can determine if a person has AD. Health care providers use a patient’s medical history, mental status tests, physical and neurological exams, and diagnostic tests to diagnose AD and other types of dementia. During the neurological exam, reflexes, coordination, muscle tone and strength, eye movement, speech, and sensation are tested.

Mental status testing evaluates memory, thinking, and simple problem-solving abilities. Some tests are brief, whereas others can be more time-intensive and complex. These tests give an overall sense of whether a person is aware of their symptoms; knows the date, time, and place where they are; can remember a short list of words; and if they can follow instructions and do simple calculations. The Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) and Mini-Cog test are two commonly used assessments.

During the MMSE, a health professional asks a patient a series of questions designed to test a range of everyday mental skills. The maximum MMSE score is 30 points. A score of 20-24 suggests mild dementia, 13-20 suggests moderate dementia, and less than 12 indicates severe dementia. On average, the MMSE score of a person with AD declines about two to four points each year.

During the Mini-Cog, a person is asked to complete two tasks: remember and then later repeat the names of three common objects and draw a face of a clock showing all twelve numbers in the right places with the time indicated as specified by the examiner. The results of this brief test determine if further evaluation is needed. In addition to assessing mental status, the health care provider evaluates a person’s sense of well-being to detect depression or other mood disorders that can cause memory problems, loss of interest in life, and other symptoms that can overlap with dementia.

Diagnostic testing for AD may include structural imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). These tests are primarily used to rule out other conditions that can cause symptoms similar to Alzheimer’s but require different treatment. For example, structural imaging can reveal brain tumors, evidence of strokes, damage from head trauma, or a buildup of fluid in the brain.[9]

Treatment with Medications

Although there is no cure for AD, there are medications to help lessen symptoms of memory loss and confusion and interventions to manage common symptomatic behaviors. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two types of medications–cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine– to treat the cognitive symptoms of AD (memory loss, confusion, and problems with thinking and reasoning). As AD progresses, brain cells die and connections among cells are lost, causing cognitive symptoms to worsen. Although current medications cannot stop the damage AD causes to brain cells, they may help lessen or stabilize symptoms for a limited time by affecting certain chemicals involved in carrying messages among the brain’s nerve cells. Sometimes both types of medications are prescribed together.[10]

Cholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed to treat early to moderate symptoms of AD related to memory, thinking, language, judgment, and other thought processes. Cholinesterase inhibitors prevent the breakdown of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that is vital for learning and memory. It supports communication among nerve cells by keeping acetylcholine levels high and delays or slows the worsening of symptoms. Effectiveness varies from person to person, and the medications are generally well-tolerated. If side effects occur, they commonly include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, and increased frequency of bowel movements. These three cholinesterase inhibitors are commonly prescribed[11]:

- Donepezil (Aricept), approved to treat all stages of AD

- Galantamine (Razadyne), approved for mild to moderate stages

- Rivastigmine (Exelon), approved for mild to moderate stages

Memantine (Namenda) and a combination of memantine and donepezil (Namzaric) are approved by the FDA for treatment of moderate to severe AD. Memantine is prescribed to improve memory, attention, reasoning, language, and the ability to perform simple tasks. Memantine regulates the activity of glutamate, a chemical involved in information processing, storage, and retrieval. It improves mental function and the ability to perform daily activities for some people, but it can cause side effects, including headache, constipation, confusion, and dizziness.

Other medications may be prescribed to treat specific symptoms of depression, anxiety, or psychosis. However, the decision to use an antipsychotic drug must be considered with extreme caution. Research has shown that these drugs are associated with an increased risk of stroke and death in older adults with dementia. The FDA has ordered manufacturers to label such drugs with a Black Box Warning about their risks and a reminder that they are not approved to treat dementia symptoms. Individuals with dementia should use antipsychotic medications only under one of the following conditions:

- Behavioral symptoms are due to mania or psychosis.

- The symptoms present a danger to the person or others.

- The person is experiencing inconsolable or persistent distress, a significant decline in function, or substantial difficulty receiving needed care.

Antipsychotic medications should not be used to sedate or restrain persons with dementia. The minimum dose should be used for the minimum amount of time possible, and nurses should carefully monitor for adverse side effects and report them to the health care provider.[12]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- National Institute on Aging. (2019). Alzheimer’s disease fact sheet. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet ↵

- “Alzheimers_Disease.jpg” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and “24239522109_6b061a9d69_o.jpg” by NIH Image Gallery is licensed under CC0 ↵ ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

- Ouldred, E., & Bryant, C. (2008). Dementia care. Part 1: Guidance and the assessment process. British Journal of Nursing, 17(3), 138-145. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2008.17.3.28401 ↵

- “civilian-service-63616_960_720.jpg” by geralt is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

An irreversible, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills and eventually the ability to carry out the simplest tasks. It is the most common cause of dementia.

A significant warning from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that alerts the public and health care providers to serious side effects, such as injury or death.