8.2 Basic Concepts of Bipolar Disorders

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar disorders are serious and complex disorders, often necessitating periods of inpatient care combined with lifelong outpatient care. Bipolar disorders include shifts in mood from abnormal highs (called manic episodes) to abnormal lows (i.e., depressive episodes). People experiencing a manic episode may exhibit dangerous, impulsive behaviors that may result in death. They may become physically exhausted. While the manic phase is associated with dramatic changes in behavior, patients with a bipolar disorder spend more time in the depressive phase. The mortality ratio due to suicide for people experiencing the depressive phase of bipolar disorder is 20 times higher than that of the general population rate and exceeds rates for other mental health disorders.[1] Treatment can ease many symptoms, yet patients may not adhere to medication plan due to adverse effects or impaired judgment. The age of onset of bipolar disorders is in the late teens and twenties and may impair the normal developmental activities of this age, such as education, work, and relationships.

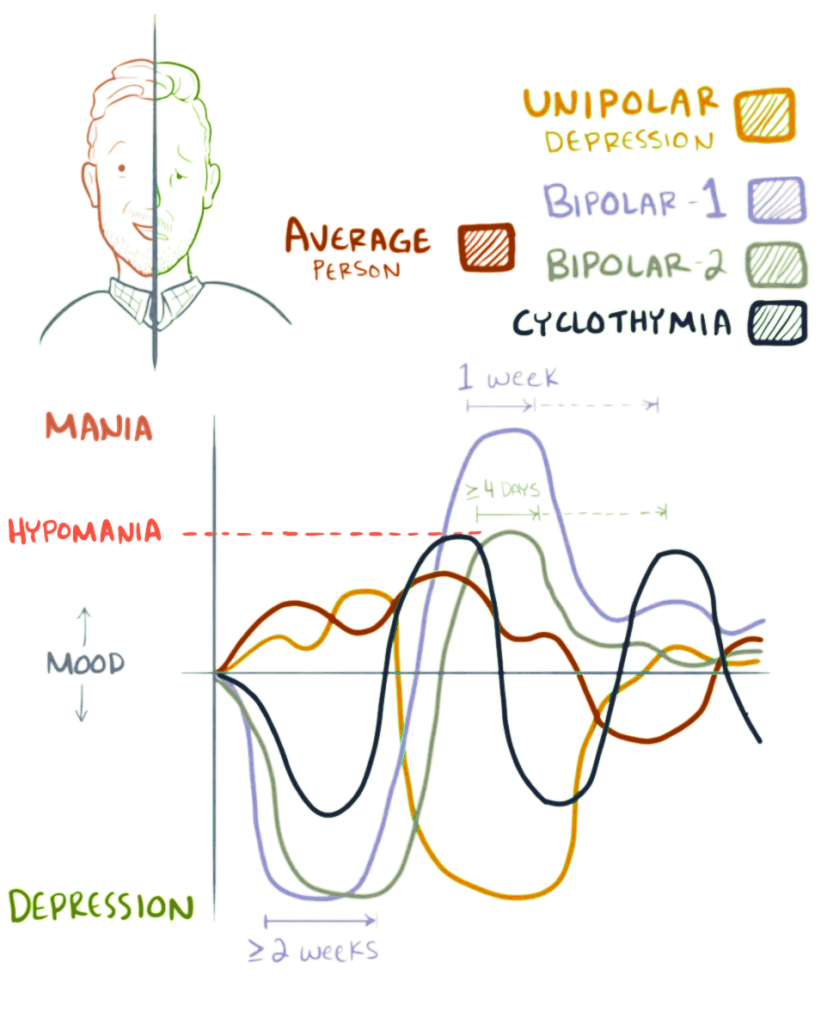

Current diagnostic criteria list three major types of bipolar and related disorders called Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and Cyclothymia. See Figure 8.2[2] for an illustration comparing these three types of bipolar disorders. Unipolar, or major depression, is included for comparison.

Figure 8.2 Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar I Disorder is notable for the severity of the elevated mood. Individuals with Bipolar 1 Disorder have had at least one manic episode and often experience additional hypomanic and depressive episodes. (Read about the symptoms of depressive episodes in the Chapter 7.3.) One manic episode in the course of an individual’s life can change an individual’s diagnosis from major depressive disorder to bipolar disorder. Manic episodes last at least one week and present for most of the day, nearly every day. They can be so severe that the person requires hospitalization. Depressive episodes typically last at least two weeks. Episodes of depression with mixed features (having depressive symptoms and manic symptoms at the same time) are also possible.[3],[4] Bipolar II Disorder is defined by a pattern of depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes, but individuals have never met the criteria for a full manic episode typical of Bipolar I Disorder. Individuals with Bipolar II Disorder often have higher productivity when they are hypomanic but may exhibit increased irritability.[5]

Cyclothymia is defined by periods of hypomanic symptoms and depressive symptoms lasting for at least two years (one year in children and adolescents). However, the symptoms do not meet the diagnostic requirements for hypomanic episodes or depressive episodes.[6] Individuals with cyclothymia do not experience the same severity or impairment in functioning as seen in individuals with bipolar disorder. Individuals with cyclothymia are often able to maintain work, personal relationships, etc.

Read more on the National Institute of Mental Health’s Bipolar Disorder webpage.

Some people with Bipolar I or Bipolar II disorders experience rapid cycling with at least four mood episodes in a 12-month period. These mood episodes can be manic episodes, hypomanic episodes, or major depressive episodes. Cycling can also occur within a month or even a 24-hour period. Rapid cycling is associated with severe symptoms and poorer functioning and is more difficult to treat.[7]

Manic Episodes

As stated above, manic episodes are hallmarks of bipolar disorder. A manic episode is a persistently elevated or irritable mood with abnormally increased energy lasting at least one week. The mood disturbance is severe and causes marked impairment in social or occupational function. As the manic episode intensifies, the individual may become psychotic with hallucinations, delusions, and disturbed thoughts. The episode is not caused by the physiological effects of a substance or medication or by another medical condition. According to the DSM-5, three or more of the following symptoms are present during a manic episode[8]:

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity

- Decreased need for sleep (i.e., feels rested after only three hours of sleep)

- More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking

- Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing

- Distractibility (i.e., attention is too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant stimuli)

- Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation

- Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments)

Hypomanic episodes have similar symptoms to a manic episode but are less severe and may not cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning or require hospitalization.[9]

Coexisting Disorders

It is common for people with bipolar disorder to have comorbid disorders, such as an anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or a personality disorder. Sometimes, a person with severe episodes of mania or depression may experience psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions, resulting in an incorrect diagnosis of schizophrenia. People with bipolar disorder may misuse alcohol or drugs and engage in other high-risk behaviors in times of impaired judgment during manic episodes. In some cases, people with bipolar disorder also have an eating disorder, such as binge eating or bulimia.[10]

Causes of Bipolar Disorder

Researchers continue to study the possible causes of bipolar disorder. Similar to depressive disorders, most experts agree there is no single cause, and there are many factors that contribute to bipolar disorder. Research shows that people who have a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder have an increased chance of having the disorder. People with certain genes are more likely to develop bipolar disorder. Newer research indicates altered intracellular calcium signaling occurs in people with bipolar disorders, and antiseizure medications can provide effective treatment.[11],[12]

Stress is a common trigger for mania and depression in adults, and previous adverse childhood events (ACEs) are significantly associated with bipolar disorder.[13] For example, a person with an unstable, chaotic childhood may experience bipolar disorder later in adulthood that is triggered by extreme stress. Read more about adverse childhood events (ACEs) in the Chapter 1.2.

Physiological causes can also cause mania-like symptoms. For example, hyperthyroidism can cause difficulty sleeping, irritability, anxiety, and unintentional weight loss. Individuals can also experience substance-induced bipolar symptoms that develop during intoxication by a substance or withdrawal from a substance. For example, alcohol, sedatives, cocaine, methamphetamines, and phencyclidine (PCP) can cause bipolar-like symptoms.[14] For these reasons, on initial evaluation of a patient experiencing a manic episode, screening is often typically performed for thyroid disorders and substance use.

- Baldessarini, R.J., Vázquez, G.H. & Tondo, L. (2020, January 6). Bipolar depression: A major unsolved challenge. International Journal of Bipolar Disorders 8, (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-019-0160-1 ↵

- “Bipolar_mood_shifts.png” by Osmosis is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Jain, A. & Mitra, P. (2023, February 20). Bipolar disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558998/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Jain, A. & Mitra, P. (2023, February 20). Bipolar disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558998/ ↵

- Jain, A. & Mitra, P. (2023, February 20). Bipolar disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558998/ ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2020, January). Bipolar disorder. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/bipolar-disorder ↵

- Jain, A. & Mitra, P. (2023, February 20). Bipolar disorder. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558998/ ↵

- Harrison, P.J., Geddes, J.R., & Tunbridge, E.M. (2019) The emerging neurobiology of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry online(17)3. Retrieved from psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.focus.17309 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

The most severe bipolar disorder with at least one manic episode; most individuals experience additional hypomanic and depressive episodes.

A pattern of depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes, but individuals have never experienced a full-blown manic episodes typical of Bipolar I Disorder.

A disorder defined by periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms lasting for at least two years (1 year in children and adolescents).

At least four mood episodes associated with bipolar disorder occurring in a 12-month period.

A persistently elevated or irritable mood with abnormally increased energy lasting at least one week.

Episodes similar to symptoms of a manic episode, but they are less severe and do not cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning or require hospitalization.