11.3 Schizophrenia

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness that affects how a person thinks, feels, and behaves. It also affects the person’s ability to recognize their symptoms as problematic, referred to as a “lack of insight” or anosognosia. Continuous signs of the disturbance must be present for at least six months in order for schizophrenia to be diagnosed, and potential medical conditions that could be causing delirium must be ruled out. [1] [2]

Schizophrenia is typically diagnosed in the late teen years to the early thirties and tends to emerge earlier in males than females. A diagnosis of schizophrenia often follows the first episode of psychosis when individuals first display symptoms of schizophrenia. Gradual changes in thinking, mood, and social functioning often begin before the first episode of psychosis, usually starting in mid-adolescence. (See “Psychosis” in the previous Chapter.) Schizophrenia can occur in younger children, but it is rare for it to occur before late adolescence. [3]

Symptoms of Schizophrenia

Symptoms of schizophrenia are classified in categories that are useful for diagnosis and treatment: positive, negative, and cognitive.[4]

- Positive symptoms: Positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, thought disorders, disorganized speech, and alterations in behaviors. Positive symptoms are thoughts and behaviors that are ‘added to’ the individual’s clinical picture; they are not normally present. Read more about delusions and hallucinations in Table 3.2’s “Thought and Perception” section in Chapter 3.3. The most common types of delusions experienced by individuals with schizophrenia are paranoia, persecutory, grandiose, or religious ideas. For example, an individual with persecutory delusions may feel the nursing staff is trying to poison them when they administer medications. People with psychotic symptoms lose a shared sense of reality and experience the world in a distorted way.[5] For more on assessing a patient with psychotic symptoms, see Chapter 3.3 .

-

- Hallucinations: Hallucinations are disturbances in perception; the patient experiences sensory events that have no basis in reality. A person may see, hear, smell, taste, or feel things that are not actually there. Examples include hearing voices or music, seeing images, the feeling that insects are crawling on one’s skin, and a persistent sensation of a bad taste or smell. Hearing voices (auditory hallucinations) is common for people with schizophrenia. People who hear voices may hear them for a long time before family or friends notice a problem. A command hallucination is a dangerous type of auditory hallucination. The patient will report that the voice(s) are telling him or her to perform an act, often harming the self or someone else. Command hallucinations will be discussed more fully in the next section due to their impact on safety for the patient and staff.

- Delusions: Delusions are fixed false beliefs that are not true and may seem irrational to others. For example, individuals experiencing delusions may believe that people on the radio and television are sending special messages that require a certain response, or they may believe that they are in danger or that others are trying to hurt them. Some common types are:

- Persecutory or Paranoid: A belief that one is being persecuted or plotted against. Patients may believe they are being followed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation or may have a tracking device implanted. They may believe that they will be poisoned. This is the most common type of delusion and can lead to noncompliance with treatment.

- Grandiose: A belief that one is overly important, powerful, or revered. They may believe they have special knowledge or power. Some grandiose delusions have religious overtones.

- Disordered Thoughts as Manifested in Speech: A person with schizophrenia may have ways of thinking that are unusual or illogical. Their speech will reflect these distortions. People with thought disorder may have trouble organizing their thoughts and speech. Sometimes a person will stop talking in the middle of a thought (thought blocking), jump from topic to topic (flight of ideas), or make up words that have no meaning (neologisms). Other types of disorganized speech include:

-

- Echolalia: pathological repeating words that someone else has just said.

- Circumstantiality: Adding excessive detail to a statement but eventually getting to the main idea.

- Tangentiality: Wandering off a topic and never returning to the main idea.

- Pressured speech: Urgent and intense speech with no tolerance for interruptions.

- Thought insertion or deletion: A perception that thoughts are being placed in or removed from one’s brain

-

- Negative symptoms: Negative symptoms refer to loss of motivation, disinterest or lack of enjoyment in daily activities, social withdrawal, difficulty showing emotions, and difficulty functioning normally. These can be conceptualized as a ‘taking away’ of qualities that involve humanness and joy. Many of these symptoms start with the letter “A”. Individuals typically experience the following negative symptoms[6]]:

- Avolition: Reduced motivation and difficulty planning, beginning, and sustaining activities.

- Anhedonia: Diminished feelings of pleasure in everyday life.

- Affective blunting: Reduced affect, or expression of emotion, flat affect. The affect may inappropriate or bizarre.

- Alogia: Reduced output of speech.

- Asociality: Reduced interaction and involvement with others.

- Apathy: Decreased interest in activities or beliefs that would normally be interesting.

- Cognitive symptoms: Cognitive symptoms refer to problems in attention, concentration, and memory. For some individuals, the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia are subtle, but for others, they are more prominent and interfere with activities like following conversations, learning new things, or remembering appointments. Individuals typically experience symptoms such as these[7]:

- Difficulty processing information to make decisions

- Problems using information immediately after learning it

- Trouble focusing or paying attention

- Concrete thinking or inability to think abstractly

- Memory difficulty

- Anosognosia – lack of insight into having an illness

- Other symptoms: Patients with schizophrenia may exhibit behaviors and movements that are unusual.

- Catatonia: A pronounced abnormality of movement and behavior arising from a disturbed mental state that may involve repetitive or purposeless activities. A particularly dangerous form of slowed movement is catalepsy, in which the patient exhibits muscular rigidity and lack of movement so severe that the limbs remain in whatever position they are placed. If persistent, this condition may lead to dehydration, malnutrition, and exhaustion.

- Some patients will pace incessantly, even knocking others over (motor agitation). Others will exhibit greatly slowed movement (motor retardation). Additional behaviors include posturing, poor recognition of physical boundaries between people, mimicking movements of others (echopraxia), and poor impulse control.

See the following box for signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the DSM-5.

DSM-5: Symptoms of Schizophrenia[8]

Schizophrenia is diagnosed when two (or more) of the following characteristics are present for a significant portion of time during a one-month period (or less if successfully treated). At least one symptom is delusions, hallucinations, or disorganized speech:

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Disorganized speech (i.e., frequent derailment or incoherence)

- Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior. (Catatonia is a state of unresponsiveness.)

- Negative symptoms (i.e., diminished emotional expression or avolition.) Avolition refers to reduced motivation or goal-directed behavior.

Additionally, for a significant portion of time, the patient’s level of functioning in one or more areas, such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care, is significantly below their prior level of functioning. Continuous signs of schizophrenia persist for at least six months (or less if it is successfully treated). Depressive or bipolar disorders with psychotic features must have been previously ruled out, and the disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or other medical condition. The provider may specify if this is the first episode or multiple episodes and if it is an acute episode, in partial remission, or in full remission.[9]

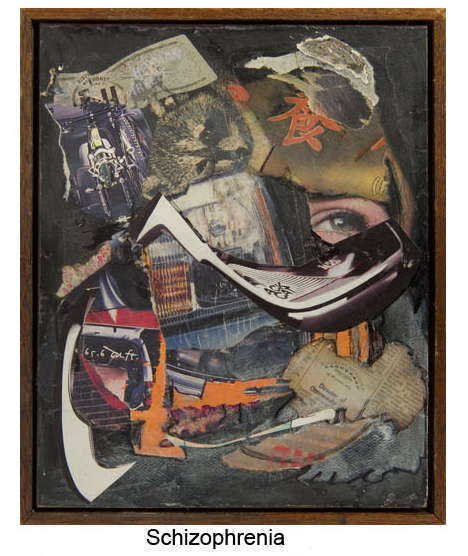

See Figure 11.3a[10]

Phases of Schizophrenia

Prodromal and Premorbid schizophrenia symptoms

The first signs and symptoms of schizophrenia may be overlooked because they’re common to many other conditions. It’s often not until schizophrenia has advanced to the active phase that the prodromal phase is recognized and diagnosed.[11]

Symptoms in this phase may include:

- withdrawal from social life or family activities that were previously enjoyed

- isolation

- increased anxiety

- difficulty concentrating or paying attention at school or work

- lack of motivation

- impaired decision-making

- changes to normal routine

- forgetting or neglecting personal hygiene

- sleep disturbances

- increased irritability

Active schizophrenia symptoms

At this phase of schizophrenia, the symptoms may be obvious and severe and greatly impair functioning. The criteria in the DSM-5 have been met. The individual may experience his or her first hospitalization after experiencing hallucinations and/or delusions. The length of the active phase varies with the individual, even with treatment. Research suggests by the time a person is at this phase; they may have been showing symptoms of prodromal schizophrenia for approximately two years.

Symptoms include:

- hallucinations or seeing people or things no one else does

- paranoid delusions

- confused and disorganized thoughts

- disordered speech

- changes to motor behavior (such as useless or excessive movement)

- lack of eye contact

- flat affect

Residual or Maintenance schizophrenia symptoms

While no longer used in diagnosing, some clinicians may still describe this phase when discussing symptoms and the progression of schizophrenia. Symptoms in this phase of the illness resemble symptoms in the first phase, even when treatment is active. They’re characterized by low energy and lack of motivation, but some elements of the active phase remain. Some people may relapse back to the active phase. Individuals are often in the community at this point, with families or in outpatient programs. Many experience a continued chronic, relapsing course.

Symptoms of the residual phase are said to include:

- lack of emotion

- social withdrawal

- constant low energy levels

- eccentric behavior

- illogical thinking

- conceptual disorganization

Risk Factors for Schizophrenia

It is believed that several factors contribute to the risk of developing schizophrenia, including genetics, environment, and brain structure and function.[12]

Genetics

Schizophrenia tends to run in families. About 80% of the risk for schizophrenia is thought to be due to genetic factors. Genetic studies strongly suggest that many different genes increase the risk of developing schizophrenia, but that no single gene causes the disorder by itself. It is not yet possible to use genetic information to predict who will develop schizophrenia.[13]A systematic review found that cannabis (marijuana) worsens symptoms of psychosis in genetically predisposed individuals and causes more relapses and hospitalizations.[14]

Environment

Interactions between genetic risk and aspects of an individual’s environment play a role in the development of schizophrenia. Causes under study include effects of toxins, social adversity, and life changes such as a move. Environmental factors that may be involved include adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) or exposure to viruses or nutritional problems before birth.[15]

Brain Structure and Function

Researchers have posited that differences in brain structure, function, and interactions among neurotransmitters may contribute to the development of schizophrenia. For example, differences in the volumes of specific components of the brain, the manner in which regions of the brain are connected and work together, and neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, are found in people with schizophrenia. Differences in brain connections and brain circuits seen in people with schizophrenia may begin developing before birth. Changes to the brain that occur during puberty may trigger psychotic episodes in people who are already vulnerable due to genetics, environmental exposures, or the types of brain differences mentioned previously[16]

View the following YouTube video on an individual’s experience with psychosis[17]: What is Psychosis?

Treatment

Schizophrenia is a chronic disorder that has a variable course and may involve repeated hospitalizations or institutionalization. Factors that worsen the prognosis include younger age at onset, a longer duration between the onset of symptoms and the beginning of treatment, and longer periods with no treatment. Early treatment of psychosis increases the chance of a successful remission. Treatments focus on managing symptoms and solving problems related to day-to-day functioning and include antipsychotic medications, psychosocial treatments, family education and support, coordinated specialty care, and assertive community treatment.[18]

Antipsychotic Medications

Antipsychotic medications reduce the intensity and frequency of psychotic symptoms by inhibiting dopamine receptors. Certain symptoms of psychosis, such as feeling agitated and having hallucinations, resolve within days of starting an antipsychotic medication. Symptoms like delusions usually resolve within a few weeks, but the full effects of the medication may not be seen for up to six weeks.[19]

Antipsychotic medicines are also used to treat other mental health disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), severe depression, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and generalized anxiety disorder.[20]

First-generation antipsychotics(also called “typical antipsychotics”) treat positive symptoms of schizophrenia and have several potential adverse effects due to their tight binding to dopamine receptors. Medication is prescribed based on the patient’s ability to tolerate the adverse effects. Second-generation antipsychotics(also referred to as “atypical antipsychotics”) treat both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. They have fewer adverse effects because they block selective dopamine D2 receptors, as well as serotonin, so they are generally better tolerated than first-generation antipsychotics. Patients respond differently to antipsychotic medications, so it may take several trials of different medications to find the one that works best for their symptoms.[21] Third-generation antipsychotics are newer medications that do not completely block D2 receptors: they are partial agonists, meaning they allow for limited dopamine transmission. They “stabilize” dopamine effects and thereby lessen psychotic symptoms. Adverse effects are similar to the second-generation medications.

See Table 11.1 for a list of common antipsychotic medications. They are usually taken daily in pill or liquid form. Some antipsychotic medications can also be administered as injections twice a month, monthly, every three months, or every six months, which can be more convenient and improve medication adherence.

Table 11.1 Common Antipsychotic Medications[22][23]

| Medication Class | Mechanism of Action | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

| First-Generation (Typical)

Examples:

|

Postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors in the brain | |

| Second-Generation (Atypical)

Examples:

|

Postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors in the brain

Some serotonin blockade |

|

| Third Generation (Atypical)

Examples:

|

Partial agonist at dopamine receptors in the brain

Acts as a dopamine ‘stabilizer’ |

|

Black Box Warning

A Black Box Warning states that elderly clients with dementia-related psychosis treated with antipsychotic drugs are at an increased risk of death.[24]

Special Note About Clozapine

Patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia may be prescribed clozapine, a specific type of atypical antipsychotic medication. However, people treated with clozapine must undergo routine blood testing to detect a potentially dangerous side effect called agranulocytosis (extremely low white blood cell count). Clozapine also has strong anticholinergic, sedative, cardiac, and hypotensive properties and frequent drug-drug interactions.[25][26]:

- Anticholinergic symptoms: dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, or urinary retention

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Restlessness

- Weight gain

- Nausea or vomiting

- Low blood pressure

First-generation antipsychotics, also known as neuroleptics or typical antipsychotics, have significant potential to cause extrapyramidal side effects and tardive dyskinesia due to their tight binding to dopamine receptors. The risk for developing these movement disorders is the primary difference between first-generation antipsychotics and second-; and third-generation antipsychotics (also known as atypical antipsychotics). The newer classes are less likely to cause movement disorders. In other respects, the two classes of medication have similar side effects.[27]

Extrapyramidal (EPS) side effects refer to akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), rigidity, bradykinesia (slowed movement), tremor, and dystonia (involuntary contractions of muscles of the extremities, face, neck, abdomen, pelvis, or larynx in either sustained or intermittent patterns that lead to abnormal movements or postures). See Figure 11.3b[28] for an image of dystonia. Anticholinergic side effects (e.g., dry mouth, constipation, and urinary retention) are common, and histamine blockage causes sedation, with chlorpromazine being the most sedating.[29]

Acute dystonic reactions affecting the larynx can be a medical emergency requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. EPS symptoms usually resolve dramatically within 10 to 30 minutes of administration of parenteral anticholinergics such as diphenhydramine and benztropine.[30]

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) is a syndrome of movement disorders thought to be due to neurologic injury that can occur in patients taking first-generation antipsychotics. Hallmark symptoms are smacking and puckering lips, eye blinking, grimacing, and twitching. TD persists for at least one month and can last up to several years despite discontinuation of the medications. Early recognition and subsequent discontinuation of the medication may eliminate the symptoms completely. However, for others, especially those who have been on the first-generation antipsychotic for years, symptoms may take years to resolve or may never resolve completely even when the medication has been stopped. Primary treatment of TD includes discontinuation of first-generation antipsychotics and may include the addition of another medication such as deutetrabenazine or valbenazine. These medications are considered first-line treatment for TD because they can limit the amount of dopamine available in areas of the brain where adverse movements originate. Clonazepam and ginkgo biloba have also shown good effectiveness for improving symptoms of TD.[31]: Understanding Tardive Dyskinesia.

Figure 11.3b Dystonia[/caption]

Figure 11.3b Dystonia[/caption]