12.5 Applying the Nursing Process to Mental Health Disorders in Children and Adolescents

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Working with children and adolescents is very different from working with adults. Young people are often reluctant participants who have been brought for care they did not seek on their own. Additionally, their communication skills are limited based on their developmental stage. In addition to gathering information from the child, information must also be obtained from the parent or caregiver.[1]

The first step to successful care is to create a therapeutic nurse-patient relationship. A therapeutic alliance can typically be created if the young person feels noticed, heard, and appreciated. It is often helpful to start the conversation with a relatively neutral question like, “Your mom/dad said that you go to ____ school. What is that school like?” School, friends, family, and favorite activities are low-stress conversation starters. For a very young child, a conversation starter could be a simple observation like what they are wearing. For example, “I see you are wearing blue tennis shoes; did you pick those out yourself?” For young people who seem reluctant to start talking, it may be helpful to describe something you saw that shows you have been paying attention to them. For example, “It looked as though it was hard for you to sit and do nothing while your dad and I were talking. What do you think?”[2]

When caring for adolescents, it is helpful to gather data from the parent or caregiver and then ask to speak with the adolescent alone. Reinforce that the conversation is “conditionally confidential” and invite the adolescent to sit alone with you to talk. It is important to inform the teen that the conversation is confidential unless there is evidence of risk for self-injury, threats to others’ wellbeing, or a revelation of harm being done to the individual by someone else. A 1:1 conversation with an adolescent typically creates a better therapeutic alliance with more honest answers obtained [3].

A more subtle strategy to build a therapeutic-nurse relationship with children and adolescents is to shape how you speak so you are perceived as a responsive problem-solving partner rather than an authority figure who will judge them. Building a therapeutic relationship with a young person should lead to learning their true chief complaint because the chief complaint of an adolescent may be different from their parents’ complaints. Furthermore, goal setting and treatment plans will be more effective when the adolescent’s concerns are addressed[4][5]

Privacy, Confidentiality, and Mandatory Reporting

Confidentiality should be discussed with the adolescent client and their parent/guardian before beginning an assessment or related conversations, and circumstances should be defined for when confidentiality is “conditional” for children and adolescents. State laws determine what information is considered confidential and what requires reporting to law enforcement or Child Protective Services. Examples of what must be reported to law enforcement include reports of child abuse, gunshot or stabbing wounds, sexually transmitted infections, abortions, suicidal ideation, and homicidal ideation. Some state laws make it optional for clinicians to inform parents/guardians if their child is seeking services related to sexual health care, substance abuse, or mental health care. Nurses should be aware of the state laws affecting the confidentiality of child and adolescent care in the state in which they are practicing. Although it is important for nurses to respect adolescent clients’ privacy and confidentiality, it is also important to encourage the adolescent to talk with their parents/guardians about personal issues that affect their health even if they feel uncomfortable doing so. Parent/guardian support can help ensure the adolescent’s health needs are met [6].

Recognizing Cues

Parents and caregivers typically bring a child or adolescent in for mental health evaluation due to common concerns, such as the following:

- Poor academic performance

- Developmental delays

- Disruptive or aggressive behavior

- Withdrawn or sad mood

- Irritable or labile mood

- Anxious or avoidant behavior

- Recurrent and excessive physical complaints

- Sleep problems

- Self-harm and suicidality

- Substance misbuse

- Disturbed eating

Poor academic performance is a common concern and may be the first clue that the child or adolescent is experiencing declining health. Keep in mind that assessing a child’s/adolescent’s ability to function in school is like assessing an adult’s ability to function at work. Many factors can affect a young person’s performance at school, such as their ability and effort, the classroom environment, life distractions, or a mental health disorder.

Recall that ability may be impacted by hearing or visual impairments, learning disorders, or cognitive impairments. The nurse may assist with performing vision or hearing tests or providing a developmental rating scale. Signs of abuse, neglect, or bullying are important for the nurse to observe and report. Read more about abuse and neglect in Chapter 15.

Psychosocial Assessment and Mental Status Examination

Specific signs and symptoms of a mental health disorder should be assessed as part of the “health history” component of a comprehensive nursing assessment. While asking questions about specific symptoms and obtaining a health history, the nurse should also be simultaneously performing a mental status examination. The mental status examination includes these items:

- Appearance and General Behavior

- Speech

- Motor Activity

- Affect and Mood

- Thoughts and Perceptions

- Attitude and Insight

- Cognitive Abilities

Review details of a mental status examination in the “Chapter 3.3.

Family Dynamics

Family dynamics refers to the patterns of interactions among family members, their roles and relationships, and the various factors that shape their interactions. Because family members typically rely on each other for emotional, physical, and economic support, they are one of the primary sources of relationship security or stress. Secure and supportive family relationships provide love, advice, and care, whereas stressful family relationships may include frequent arguments, critical feedback, and unreasonable demands. Interpersonal interactions among family members have lasting impacts and influence the development and well-being of children. Unhealthy family dynamics may be traumatic for children. Conflict between parents and adolescents is associated with adolescent aggression, whereas mutuality (cohesion and warmth) is shown to be a protective factor against aggressive behavior.[7]

Effectively assessing and addressing a client’s family dynamics and its role in a child’s or adolescent’s mental health disorder requires an interprofessional team of health professionals, including nurses, physicians, social workers, and therapists. Nurses are in a unique position to observe interaction patterns, assess family relationships, and attend to family concerns in clinical settings because they are in frequent contact with family members. Collaboration among interprofessional team members promotes family-centered care and provides clients and families with the necessary resources to develop and maintain healthy family dynamics[8].

Life Span Considerations

Childhood is a time of rapid acquisition of skills and self-concept. A healthy child exhibits trust in others and has a sense of social norms. They are curious and creative. When stress occurs, they behave in ways that are developmentally appropriate, for example crying when frightened or turning to an adult for help. Adolescence is a time of normal exploration regarding gender identity, gender roles, and sexual orientation. They are concerned with who they are becoming and who they are in relationships to others. When assessing children and adolescents, the nurse should use information about normal child development to inform the assessment process as to relevant information[9]. Please review the information in Chapter 3.3.

Cultural Considerations

The Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) is a structured tool in the DSM-5 used to assess the influence of culture on a client’s experience of distress. See the following box for an adapted version of the CFI tool for children and adolescents.[10]

Nurses customize nursing diagnoses based on the child’s or adolescent’s response to mental health disorders, their current signs and symptoms, and the effects on their and their family’s functioning. Here are common nursing concerns related to childhood and adolescent disorders[11],[12],[13]: The highest importance is placed on risk for suicide, risk for injury to self, and risk for other-directed violence.

- Anxiety

- Risk for injury to self/others

- Chronic low self-esteem

- Disabled family coping

- Impaired social interactions

- Ineffective impulse control

- Risk for delayed development

- Risk-prone health behavior

- Risk for impaired parenting

- Risk for spiritual distress

Consider Adverse Childhood Events

It is not known why some children develop disruptive behavior disorders, but children are at greater risk if they are exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Toxic stress from ACEs can alter brain development and affect how the body responds to stress. ACEs are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance abuse. Children with three or more reported ACEs, compared to children with zero reported ACEs, had higher prevalence of one or more mental, emotional, or behavioral disorders (36.3% versus 11.0%).[14] Review information on adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in "Chapter 1.2.

Generating Solutions

Broad goals focus on reducing symptoms of mental health disorders that interfere with the child’s or adolescent’s daily functioning and quality of life. SMART outcomes stand for outcomes that are specific, measurable, achievable, and realistic with a timeline indicated. They are customized according to each client’s diagnoses and needs. Read more about SMART outcomes in Chapter 3.5.

For example, a SMART outcome for a child diagnosed with attention deficit disorder is, “The patient will demonstrate reduced impulsive behaviors, as reported by parents and their teachers, within two weeks of initiating stimulant medication.” A SMART outcome for a teen who has suicidal ideation is, "The patient will inform the nurse of any suicidal impulses throughout the shift" or "The patient will remain free of self-inflicted injury throughout the shift.

Preventing ACEs can help children thrive into adulthood by lowering their risk for chronic health problems and substance abuse, improve their education and employment potential, and stop ACEs from being passed from one generation to the next.[15]

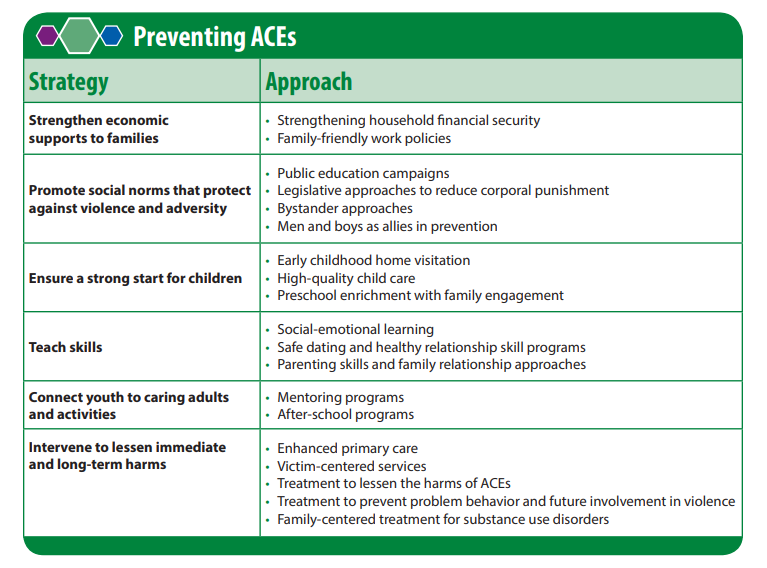

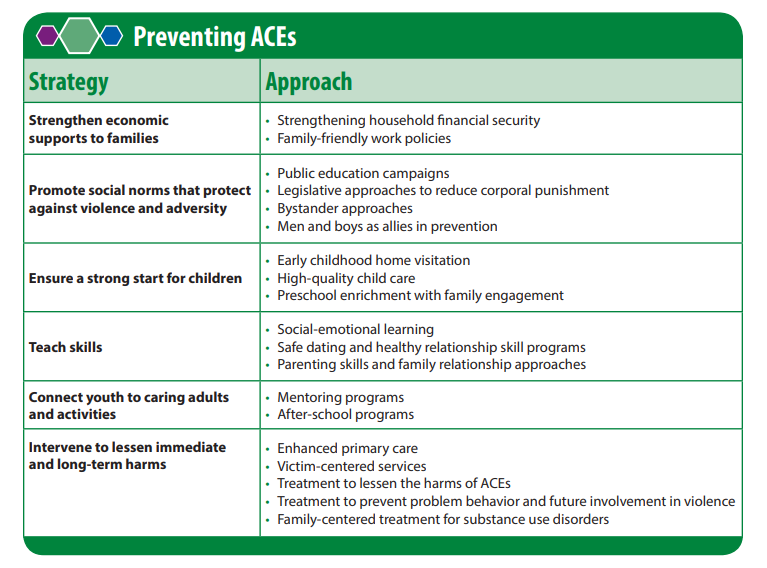

Raising awareness about ACEs can help reduce stigma around seeking help for parenting challenges, substance misuse, depression, or suicidal thoughts. Community solutions focus on promoting safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments where children live, learn, and play. In addition to raising awareness and participating in community solutions, nurses should recognize ACE risk factors and refer clients and their families for effective services and support. See Figure 12.5d[16] regarding strategies to prevent ACEs.

Read Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences [PDF] by the CDC with evidence-supporting interventions.

Taking Action

Treatment of mental health disorders in children and adolescents typically requires a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Communication and cooperation among healthcare team members is essential. Read about specific multidisciplinary treatments for various disorders in the “Chapter 12.4, “Chapter 12.2,” and Chapter 12.3. Nurses should recognize and capitalize on the client’s and family’s strengths as they develop a nursing care plan and provide education and referral to resources as appropriate.

Milieu Therapy

The milieu is the environment of the care facility, inpatient or outpatient. Facilities for children and adolescents should provide safe and developmentally appropriate activities as well as a physical setting that provides for physical activity, play, and rest. Ideally, young children should be separated from adolescents due to differing developmental and mental health needs. Unit personnel should be familiar with the needs of youth and appropriate communication techniques.

Safety from Self-Harm

Like adults, children and adolescents may suffer from suicidal ideation and self-harm behaviors. These signs and symptoms are often the reasons for admission to inpatient care. Care for individuals with suicidal thoughts, attempts, and non-suicidal self-injury is covered in Chapter 2.5.

Behavioral Management

Safety risks also occur from patients' interactions with others. Some mental health disorders are associated with diminished impulse control and mood instability, making caring for youth challenging. Nurses and healthcare staff can manage a child’s or adolescent’s disruptive behaviors by implementing many different types of interventions[17]:

- Behavioral contract: A verbal or written agreement is made between the client and other parties (e.g., nurses, parents, or teachers) about behaviors, expectations, and needs. The contract is periodically reviewed with positive and negative reinforcement provided.

- A system of points or privileges: Positive behaviors need recognition and strengthening. If a patient is completing expectations, a privilege may be added. An example of a privilege is choosing a movie to watch.

- Collaborative and proactive solutions: The identification of problematic behaviors, their specific triggers, and mutually agreeable solutions. Working with the patient builds trust and respect.

- Role playing: The nurse or client acts out a specific role so the patient can practice new behaviors or skills in specific situations.

- Planned ignoring: When behaviors are determined to be attention-seeking and not dangerous, they may be ignored. Positive reinforcement is provided for on-task actions.

- Signals or gestures: An adult uses a word, gesture, or eye contact to remind the child to use self-control. For example, placing one’s finger to one’s lips and making eye contact may be used to remind a child to remain quiet during a quiet activity.

- Physical distance: It may be helpful to move closer to a child for a calming effect. However, some children may find this agitating and require more space and less physical closeness. Some children and teens need to be separated for the duration of their time in a care setting due to interpersonal conflicts or inappropriate attraction to one another.

- Redirection: The engagement of an individual in an appropriate activity after an undesirable action.

- Humor: Appropriate joking can be used as a diversion to help relieve feelings of guilt or fear.

- Restructuring: The process of changing an activity to reduce stimulation or frustration. Some patients become overstimulated by loud activities or physical activities.

- Limit setting: The process of giving direction, stating an expectation, or telling a child what to do or where to go. Caregivers and/or staff should do this firmly, calmly, and consistently without anger, preferably in advance of problem behavior occurring. For example, “I would like you to stop turning the light on and off.”

- Simple restitution: The individual is expected to correct the adverse effects of their actions, such as apologizing to the people affected or returning upturned chairs to their proper position.

Restrictive Interventions

Time-Out

Time-out is a strategy for shaping a child's behavior through selective and temporary removal of the child's access to desired attention, activities, or other reinforcements following a behavioral transgression. This strategy works for children who experience regular positive praise and attention from their parents or caregivers because they feel motivated to maintain that positive regard. The length of time should be about one minute for each year of age, but adjustments need to be made based on the child's developmental level. For example, children with developmental delays should have shorter durations.

Tips for caregivers implementing time-outs include the following[18]:

- Set consistent limits to avoid confusion.

- Focus on changing priority misbehaviors rather than everything at once.

- After setting a "time-out," decline further verbal engagement until a "time-in."

- Ensure time-outs occur immediately after misbehavior rather than being delayed.

- Follow through if using warnings (e.g., "I'm going to count to three...").

- State when the time-out is over. Setting a timer can be helpful.

- When the time-out finishes, congratulate the child on regaining personal control and then look for the next positive behavior to praise.

- Give far more positive attention than negative attention.

Seclusion and Restraints

As a last resort, seclusion or restraints, may be implemented to keep the patient or others around them safe.[19] Seclusion may include the child being removed from an activity and being confined to one's room for a period of time. Restraints are rarely used due to psychological harm. Patients in seclusion or restraints must be continuously monitored. Hydration, elimination, comfort, and other psychological and physical needs must be monitored regularly and addressed per agency policy.[20] Time in seclusion should be as short as possible. After the child or adolescent is calm, staff should include the child in a debriefing session and discuss the events leading up to the restrictive interventions to explore ways it may have been prevented.[21]

Promoting Communication and Trust

Focusing on the Individual

The nurse should spend time with each child or adolescent individually to establish build trust and to tailor care. Nurses should follow the patient's lead, if possible. caregivers follow the child's lead. Tips for caregivers implementing special time include the following[22][23]:

- Commit to setting aside a regular time during the shift.

- The time allotted should be age-appropriate and realistic for the nurse, so that it happens reliably. Five to fifteen minutes is often enough.

- Ensure this time happens no matter how positive or negative the day's behaviors were.

- Allow the child to select to guide the topic as much as possible. Focus on exploring.

Addressing Bullying

Bullying occurs when a person seeks to harm, intimidate, or coerce someone perceived as vulnerable. If there is a sudden change in a child's mood, behavior, sleep, body symptoms, academic performance, or social functioning, there is a possibility they are experiencing bullying. Cyberbullying is a significant public health concern with rates of cyberbullying estimates ranging from 14 to 57%.[24] Bullying is important for nursing care in that many young patients have experienced bullying due to having a developmental or mental disorder. Furthermore, some patients exhibit bullying tendencies toward their peers while hospitalized. Nurses have the opportunity to address both the victims and the perpetrators.

Assess for bullying by asking, "Sometimes kids get picked on or bullied. Have you ever seen this happen? Has it ever happened to you?" If the child responds "No" but bullying is suspected, communicate your concerns to the healthcare team. Let children know that bullying is unacceptable and that help is available. If staff observe one patient bullying another, take the perpetrator aside and clearly explain the problem behavior and set limits on it with consequences. Explore with the child the reasons behind the behavior (not fitting in, few friendships, outside stressors). Involve the child in making amends.

Encourage Self-Reflection and Growth

When an individual is sad or anxious, they are less likely to recognize and engage in activities and topics that formerly had meaning. Withdrawal and isolation can result and worsen the mood. The following is a list of tips to share with patients[25][26]:

- Engage in expressive activities that clarify emotions and reflection, such as art therapy or journaling.

- Write specific, realistic goals for each day for participation, engagement in therapy, and behavior.

- Participate in activities with others in the setting. Adolescents, especially, can benefit from the experiences of their peers and gain social skills.

- Let others know about feelings and concerns and enlist their help.

Address the Basics

Sleep

Insomnia is a common problem among children and adolescents. For some, the home environment is notable for inconsistent daily patterns. For others staying connected via social media or texting may take priority over sleep. Most sleep problems can be resolved by changing habits and routines that affect sleep, commonly referred to as sleep hygiene. Nurses in the inpatient setting can ensure hygiene measures and teach patients and their families about beneficial changes to routines. The following is a list of tips for caregivers for improving sleep hygiene[27]:

- Maintain consistent bedtimes and wake times every day of the week in the hospital and at home.

- Maintain a routine of pre-sleep activities (e.g., brush teeth, read a book).

- Avoid spending non-sleep time in or on one's bed. (i.e., "beds are for sleep only").

- Ensure the bedroom is cool and quiet. Efforts should be made to move noisy roommates to another room.

- Avoid highly stimulating activities just before bed (e.g., television, video games, social media, or exercise).

- Do not keep video games, televisions, computers, or phones in a child's bedroom at home.

- Exercise earlier in the day to help with sleeping later.

- Avoid caffeine in the afternoons and evenings. Caffeine causes shallow sleep and frequent awakenings.

- Encourage children and adolescents to discuss any worries with the nurse or caregiver before bed rather than ruminating on it during sleep time.

- Ensure that children go to bed drowsy but still awake. Falling asleep in places other than a bed forms habits that are difficult to break.

- Use security objects with young children who need a transitional object with which to feel safe and secure when their caregiver is not present (e.g., a special blanket or toy)

- When checking on a young child at night, briefly reassure the child you are present and they are OK.

- Avoid afternoon naps for all but very young children because they often interfere with nighttime sleep.

- If a child or adolescent is having sleep difficulties, keep a sleep diary to track sleep time, wake time, activities, and naps to identify patterns.

Nutrition

In the inpatient setting, meals are provided, often in a cafeteria-style setting. Staff should observe that patients are choosing a variety of foods and consuming adequate amounts. Snacks are also important, especially for undernourished children.

Family Education and Support

Education of family members is a key component for treating child and adolescent mental health disorders. Parents may be confused and worried about what their child has gone through. Parent Training programs can be helpful as discussed in Chapter 12.4. Nurses, along with the healthcare team should, communicate frequently about treatments the child is receiving. Discharge teaching should include medication information, follow-up care appointments, and any specialized services the patient may need.

Family members can also be encouraged to attend support groups or group education. Group education can be useful for learning how other families solve problems and build on strengths while developing insight and improved judgment about their own family.[28] Support groups are available for a number of conditions, such as ADHD and ASD. The National Alliance on Mental Illness has excellent information for families.

Find support groups for many disorders near you at Psychology Today’s Support Groups.

Read about services available through the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

Prevention of Adverse Childhood Events

Preventing adverse childhood events (ACEs) can help children thrive into adulthood by lowering their risk for chronic health problems and substance abuse, improve their education and employment potential, and stop ACEs from being passed from one generation to the next.[29]

Raising awareness about ACEs can help reduce stigma around seeking help for parenting challenges, substance misuse, depression, or suicidal thoughts. Community solutions focus on promoting safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments where children live, learn, and play. In addition to raising awareness and participating in community solutions, nurses should recognize ACE risk factors and refer clients and their families for effective services and support. See Figure 12.5d[30] regarding strategies to prevent ACEs.

Read Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences [PDF] by the CDC with evidence-supporting interventions.

Evaluation

Evaluation focuses on monitoring a child’s and adolescent’s progress towards meeting their individualized SMART goals and the revision of the nursing care plan as needed. Patient progress monitoring may include symptom management, behavior management, academic performance, activities of daily living, and socialization. The nurse also monitors effectiveness of medications, interprofessional treatments, support groups, and community resources for the patient’s families.

- Bell, J. & Condren, M. (2016). Communication strategies for empowering and protecting children. Journal of pediatric pharmacological therapy, 21(2) 176-184. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.176 ↵

- Bell, J. & Condren, M. (2016). Communication strategies for empowering and protecting children. Journal of pediatric pharmacological therapy, 21(2) 176-184. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.176 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Bell, J. & Condren, M. (2016). Communication strategies for empowering and protecting children. Journal of pediatric pharmacological therapy, 21(2) 176-184. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.176 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Pathak, P.R. & Chou, A. (2019). Confidential care for adolescents in the U.S. health care system. J Patient Cent Res Rev6(1):46-50. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1656. PMID: 31414023; PMCID: PMC6676754 ↵

- Jabbari, B., Schoo, C., & Rouster, A.S. (2023, September 16). Family dynamics. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560487/ ↵

- Jabbari, B., Schoo, C., & Rouster, A.S. (2023, September 16). Family dynamics. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560487/ ↵

- Bell, J. & Condren, M. (2016). Communication strategies for empowering and protecting children. Journal of pediatric pharmacological therapy, 21(2) 176-184. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.176 ↵

- Jabbari, B., Schoo, C., & Rouster, A.S. (2023, September 16). Family dynamics. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560487//[footnote]

Adapted Cultural Formulation Interview for Children and Adolescents[footnote]Jabbari, B., Schoo, C., & Rouster, A.S. (2023, September 16). Family dynamics. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560487//[footnote].

- Suggested introduction to the child or adolescent: We have talked about the concerns of your family. Now I would like to know how you are feeling about being ___ years old.

- Feelings of age appropriateness in different settings: Do you feel you are like other people your age? In what way? Do you sometimes feel different from other people your age? In what way?

- If they acknowledge sometimes feeling different: Does this feeling of being different happen more at home, at school, at work, and/or some other place? Do you feel your family is different from other families? Does your name have special meaning for you? Is there something special about you that you like or are proud of?

- Age-related stressors and supports: What do you like about being at home? At school? With friends? What don’t you like at home? At school? With friends? Who is there to support you when you feel you need it? At home? At school? Among your friends?

- Age-related expectations: What do your parents or grandparents expect from a person your age in terms of chores, schoolwork, play, or religion? What do your teachers expect from a person your age? What do other people your age expect from a person your age? (If they have siblings, what do your siblings expect from a person your age?)

- Transition to adulthood (for adolescents): Are there any important celebrations or events in your community that recognize reaching a certain age or growing up? When is a youth considered ready to become an adult in your family or community? What is good about becoming an adult in your family? In school? In your community? How do you feel about “growing up”? In what ways are your life and responsibilities different from your parents’ life and responsibilities?

Analyzing Cues, and Generating and Prioritizing Hypotheses

Health care professionals use the guidelines in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) to diagnose mental health disorders in children.[footnote]American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵ - Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Ackley, B., Ladwig, G., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (12th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 24). Data and statistics on children’s mental health. www.cdc.gov/children-mental-health/data-research/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, November 5). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html ↵

- This image is derived from “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence” by National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention and is in the Public Domain ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Knox, D. K., & Holloman, G. H., Jr. (2012). Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: Consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA Seclusion and Restraint Workgroup. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6867 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Bell, J. & Condren, M. (2016). Communication strategies for empowering and protecting children. Journal of pediatric pharmacological therapy, 21(2) 176-184. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.176 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Zhu, C., Huang, S., Evans, R., & Zhang, W. (2021). Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Frontiers in Public Health, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.634909 ↵

- Bell, J. & Condren, M. (2016). Communication strategies for empowering and protecting children. Journal of pediatric pharmacological therapy, 21(2) 176-184. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-21.2.176 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, November 5). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html ↵

- This image is derived from “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence” by National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention and is in the Public Domain ↵

Traumatic circumstances experienced during childhood such as abuse, neglect, or growing up in a household with violence, mental illness, substance use, incarceration, or divorce.

An age-appropriate removal from an activity for a child or adolescent for a set period of time to promote self-control and self-reflection.