14.2 Substances: Overview of Use and Misuse

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

A substance is defined as a psychoactive compound with the potential to cause health and social problems, including substance use disorders. Substances can be divided into four major categories: alcohol, illicit drugs (including nonmedical use of prescription drugs), over-the-counter drugs, and other substances. Some examples of substances known to have a significant public health impact are listed in Table 14.2a. Note that new formulations or variations occur over time. Substance use refers to the use of any of the psychoactive substances listed below.

Table 14.2a Categories and Examples of Substances[1]

| Substance Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Alcohol | Beer, malt liquor, wine, and distilled spirits |

| Illicit drugs (including prescription drugs used nonmedically) |

|

| Over-the-counter drugs (used nonmedically) | Dextromethorphan, pseudoephedrine, and other cold medications |

| Other substances | Inhalants such as spray paint, gasoline, and cleaning solvents; |

For more information on current statistics related to alcohol and substance abuse, see the National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics

Legal Categories

The Controlled Substances Act is a federal law that places all controlled substances (i.e., substances regulated by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency) into one of five categories called schedules. This placement is based on the substance’s medical use, its potential for abuse or dependency, and related safety issues. For example, Schedule I drugs have a high potential for abuse and potentially cause severe psychological and/or physical dependence, whereas Schedule V drugs represent the least potential for abuse.[2] Nurses need knowledge of these schedules as part of safe medication administration and education of patients. Dependence means that when a person suddenly stops using a drug, their body goes through withdrawal, a group of physical and mental symptoms that can range from mild to life-threatening. See examples of controlled substances categorized by schedule in Table 14.2b.

Table 14.2b Examples of Substances by Schedule[3]

Schedule |

Definition |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Schedule I | No currently approved medical use and a high potential for abuse. | Heroin, LSD, MDMA (Ecstasy), peyote, and cannabis (marijuana) |

| Schedule II | High potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. Several have beneficial effects when used correctly but may be fatal with misuse. | Hydrocodone, cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, hydromorphone, meperidine, oxycodone, fentanyl, amphetamine/dextroamphetamine salts (Adderall), methylphenidate (Ritalin), and phencyclidine (PCP) |

| Schedule III | Moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Abuse potential is less than Schedule I and Schedule II drugs but more than Schedule IV. | Acetaminophen with codeine, ketamine, anabolic steroids, and testosterone |

| Schedule IV | Low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence. | Alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), zolpidem (Ambien), and tramadol (Ultram) |

| Schedule V | Lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. Generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes. | Cough medications with codeine, diphenoxylate/atropine (Lomotil), and pregabalin (Lyrica) |

Substance Misuse

Substance misuse is defined as the use of alcohol or drugs in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that could cause harm to the user or to those around them.[4] Misuse can be of low severity and temporary, but it can increase the risk for serious and costly consequences such as motor vehicle crashes; overdose death; suicide; various types of cancer; heart, liver, and pancreatic diseases; HIV/AIDS; and unintended pregnancies. Substance use during pregnancy can cause complications for the baby such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs) or neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). Substance misuse is also associated with intimate partner violence, child abuse, and neglect.[5] Substance abuse, an older diagnostic term, referred to unsafe substance use (e.g., drunk or drugged driving), use that caused legal problems, or use that continued despite failure to meet work and family responsibilities. The term “substance abuse” is now avoided by professionals because it does not accurately account for the neurobiological knowledge we now have about addictive disorders. Instead, the term “substance use disorder” is preferred and is further discussed below.[6]

Intoxication and Overdose

Intoxication refers to a disturbance in behavior or mental function during or after the consumption of a substance. Overdose is the biological response of the human body when too much of a substance is ingested. Signs of intoxication and overdose for categories of psychoactive substances are described in Chapter 14.5. Anyone can call a regional poison control center at 1-800-222-1222 for consultation regarding toxic ingestion of substances and overdoses. Poison control centers are available at all times, every day of the year. Some hospitals also have toxicologists available for bedside consultation for overdoses.

Substance-Related Disorders

Prolonged, repeated misuse of substances can produce changes to the brain that can lead to a substance use disorder. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), substance use disorder (SUD) is an illness caused by repeated misuse of substances such as alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants (amphetamines, cocaine, and other stimulants), and tobacco. All of these substances taken in excess have a common effect of directly activating the brain reward system and producing such an intense activation of the reward system that normal life activities may be neglected. Nonsubstance related disorders such as gambling disorder activate the same reward system in the brain.[7]

Substance use disorders are diagnosed based on cognitive, behavioral, and psychological symptoms. See the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria used for SUD in the following box. SUD can range from mild to severe and from temporary to chronic.[8]

DSM-5-TR Criteria for Substance Use Disorder

SUD diagnosis requires the presence of two or more of the following criteria in a 12-month period[9]:

- The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects.

- There is a craving, or a strong desire or urge, to use the substance.

- There is recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- There is continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused by or exacerbated by the effects of the substance.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use.

- There is recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- Tolerance develops to the substance, as defined by:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or the desired effect.

- There is a markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.

- Withdrawal symptoms occur when substance use is cut back or stopped following a period of prolonged use.

The disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe. Individuals exhibiting two or three symptoms are considered to have a “mild” disorder, four or five symptoms constitute a “moderate” disorder, and six or more symptoms are considered a “severe” substance use disorder.

SUDs often develop gradually due to repeated misuse of a substance, causing changes in brain areas that control reward, stress, and executive functions like decision-making and self-control. Multiple factors influence whether a person will develop a substance use disorder such as the substance itself; the genetic vulnerability of the user; and the amount, frequency, and duration of the misuse. In addition, psychosocial factors influence SUD, including co-occurring mental health conditions, personality traits, array of coping skills, trauma, family dynamics, peer group, and socioeconomic status.

Severe substance use disorders are commonly referred to as addictions. Addiction is associated with compulsive or uncontrolled use of one or more substances. Addiction is a chronic illness that has the potential for both relapse and recovery. Relapse refers to the return to substance use after a significant period of abstinence. Recovery is a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential. When positive changes and values become part of a voluntarily adopted lifestyle, this is referred to as “being in recovery.” Among the 29.2 million adults in 2020 who have ever had a substance use problem, 72.5% considered themselves to be in recovery.[10]

Although abstinence from substance misuse is a primary feature of a recovery lifestyle, it is not the only healthy feature.[11] The chronic nature of addiction means that some individuals may relapse after an attempt at abstinence, which can be a normal part of the recovery process. Relapse does not mean treatment failure. Relapse rates for substance use are similar to rates for adherence to therapies for other chronic medical illnesses. There are a variety of medications that can be prescribed to assist with relapse prevention.[12] Individuals with severe substance use disorders can respond to effective treatment and regain health and social function, referred to as remission. [13]

Many individuals seeking care in health care settings, such as primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, emergency departments, and medical-surgical units, have undiagnosed substance use disorders. Recognition and early treatment of substance use disorders can improve their health outcomes and reduce overall health care costs.[14]

Substance Use Disorder in Nurses

Health care professionals are not immune to developing SUDs. SUDs are chronic illnesses that can affect anyone regardless of age, occupation, economic circumstances, ethnic background, or gender. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) has created several resources to support and inform nurses with SUDs who are unidentified, untreated, and may continue to practice when their impairment may endanger the lives of their patients. Because of the potential safety hazards to patients, it is a nurse’s legal and ethical responsibility to report a colleague’s suspected SUD to their manager or supervisor. [15]

It can be hard to differentiate between the subtle signs of SUD and stress-related behaviors, but three significant signs include behavioral changes, physical signs, and drug diversionBehavioral changes include decreased job performance, absences from the unit for extended periods, frequent trips to the bathroom, arriving late or leaving early, and making an excessive number of mistakes including medication errors. Physical signs include subtle changes in appearance that may escalate over time; increasing isolation from colleagues; inappropriate verbal or emotional responses; and diminished alertness, confusion, or memory lapses. Signs of diversion include frequent discrepancies in opioid counts, unusual amounts of opioid wastage, numerous corrections of medication records, frequent reports of ineffective pain relief from patients, offers to medicate coworkers’ patients for pain, and altered verbal or phone medication orders[16].

Drug diversion occurs when medication is redirected from its intended destination for personal use, sale, or distribution to others. It includes drug theft, use, or tampering (adulteration or substitution). Drug diversion is a felony that can result in a nurse’s criminal prosecution and loss of license.[17]

The earlier that a nurse is diagnosed with SUD and treatment is initiated, the sooner that client safety is protected and the better the chances for the nurse to recover and return to work. In most states, a nurse diagnosed with a SUD enters a nondisciplinary program designed by the Board of Nursing for treatment and recovery services. When a colleague treated for an SUD returns to work, nurses should create a supportive environment that encourages their continued recovery[18].[

View this NCSBN video: Substance Use Disorder in Nursing.

Nonsubstance-Related Disorders

Nonsubstance-related disorders are excessive behaviors related to gambling, viewing pornography, compulsive sexual activity, Internet gaming, overeating, shopping, overexercising, and overusing mobile phone technologies. These behaviors are thought to stimulate the same addiction centers of the brain as addictive substances. However, gambling disorder is the only nonsubstance use disorder with diagnostic criteria listed in the DSM-5. See the DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of a gambling disorder in the following box. Additional research is being performed to determine the criteria for diagnosing other nonsubstance-related disorders.[19]

DSM-5 Criteria for Gambling Disorder[20]

Gambling disorder is defined as persistent and recurrent problematic gambling behavior leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as indicated by four or more of the following criteria in a 12-month period. Additionally, the gambling behavior is not better explained by a manic episode.

- Needs to gamble with increasing amounts of money to achieve the desired excitement

- Is restless or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop gambling

- Has made repeated unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop gambling

- Is often preoccupied with gambling (e.g., persistent thoughts of reliving past gambling experiences, planning the next venture, or thinking of ways to get money with which to gamble)

- Often gambles when feeling distressed (e.g., helpless, guilty, anxious, or depressed)

- After losing money gambling, often returns another day to get even (otherwise known as “chasing one’s losses”)

- Lies to conceal the extent of involvement with gambling

- Has jeopardized or lost a significant relationship, job, or educational or career opportunity because of gambling

- Relies on others to provide money to relieve desperate financial situation caused by gambling

Overview of Selected Substances

Alcohol Misuse

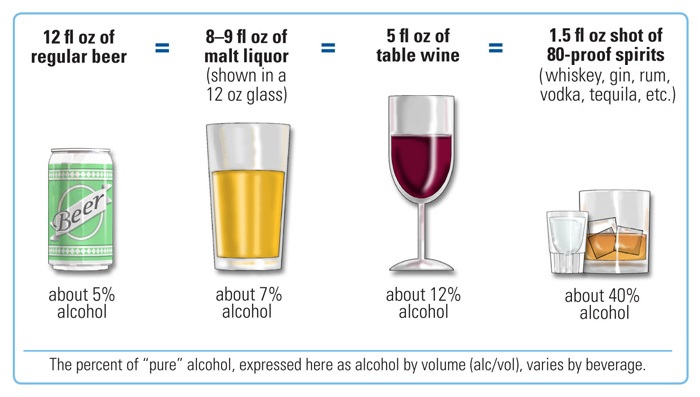

Based on the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, a standard drink is defined as 14 g (0.6 oz) of pure alcohol. Examples of a standard drink are one 12-oz beer, 8 to 9 oz of malt liquor, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of distilled spirits. See Figure 14.2b[21] for images of standard drinks.

The 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health reports that 134.7 million Americans aged 12 or older use alcohol; 45.6% were binge drinkers, and 5.8% are heavy alcohol users.[22] Binge drinking is higher in younger age groups. Heavy drinking is defined as a female consuming 8 or more drinks per week or a male consuming 15 or more standard drinks per week, or either gender binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past 30 days. Binge drinking is defined as consuming several standard drinks on one occasion in the past 30 days; for men, this refers to drinking five or more standard alcoholic drinks on one occasion, and for women this refers to drinking four or more standard drinks on one occasion. [23]. Alcohol intoxication refers to problematic behavioral or psychological changes (e.g., inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior, mood lability, or impaired judgment) that develop during or shortly thereafter alcohol ingestion. Signs and symptoms of alcohol intoxication are as follows[24]:

- Slurred speech

- Incoordination

- Unsteady gait

- Nystagmus

- Impairment in attention or memory

If there is suspicion that someone has overdosed on alcohol, seek emergency assistance or call 911.

Opioid Misuse

In 2023, 8.9 million (3.1%) of U.S. citizens aged 12 and older reported using opioids in the past year, including prescription pain relievers such as fentanyl, and heroin[25]. Opioids are substances that act on opioid receptors in the central nervous system. Medically, they are used for relief of moderate to severe pain and anesthesia. When misused, opioids cause a person to feel relaxed and euphoric (i.e., experience an intense feeling of happiness). Opioid prescription medications include Schedule II medications such as morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, fentanyl, and hydromorphone. Heroin, is also an opioid, but it is classified as a Schedule I drug.[26] Injected opioid misuse is a risk factor for contracting HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and bacterial endocarditis.

Increasing Rates of Opioid Overdose Deaths

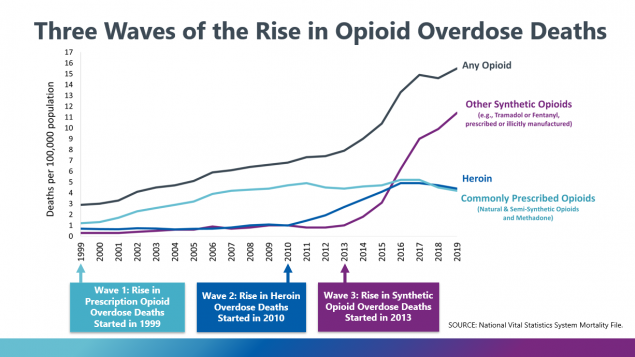

From 1999 to 2019, nearly 500,000 people died from an overdose involving prescription or illicit opioids. This increase in opioid overdose deaths can be outlined in three distinct waves. See Figure 14.2d[27] for an illustration of these three waves of opioid overdose. The first wave of overdose deaths began with the increased prescription rate of opioids in the 1990s in an attempt to more thoroughly address pain. The second wave began in 2010 with rapid increases in overdose deaths involving heroin. The third wave began in 2013 with significant increases in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly illicitly manufactured fentanyl.[28]

There are two types of fentanyl: pharmaceutical fentanyl prescribed for severe pain, and illicitly manufactured fentanyl. Most recent cases of fentanyl-related overdose are associated with illicitly manufactured fentanyl that is added to other street drugs that make them more powerful, more addictive, and more dangerous.[29]

Preventing Opioid Overdose

Nearly 85% of overdose deaths involve illicitly manufactured fentanyl, heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine. Potential opportunities to link people to care or to implement life-saving actions have been identified for more than 3 in 5 people who died from drug overdose. Circumstances that represent a potential touchpoint for linkage to care are as follows[30]:

- Bystander present: Nearly 40% of opioid and stimulant overdose deaths occurred while a bystander was present.

- Recent release from an institution: Among the people who died from overdoses involving opioids, about 10% had recently been released from an institution (such as jail/prison, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, or psychiatric hospitals). Risk increased for this population because they were unaware of decreased tolerance to the drug due to abstinence from it while in the institution.

- Previous overdose: Among the people who died from overdoses involving opioids, about 10% had a previous overdose.

- Mental health diagnosis: Among all the people who died of a drug overdose, 25% had a documented mental health diagnosis.

- Substance use disorder treatment: Among the people who died from opioid overdose, nearly 20% had previously been treated for substance use disorder.

Opioid overdoses can be prevented by helping individuals struggling with opioid use disorder find the right treatment and recovery services, as well as providing public education about administering naloxone. Read more about treatment and recovery in Chapter 14.5.

Cannabis (Marijuana) Misuse

Approximately 62 million (21.8%) of Americans aged 12 or older used cannabis (marijuana) in the past year, and 5.1% of people have a cannabis use disorder.[31][32] Changes in marijuana policies across states have legalized marijuana for recreational and/or medicinal uses (e.g., pain control, increased appetite for individuals undergoing chemotherapy, etc.). Although many states now permit dispensing marijuana for medicinal purposes, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved “medical marijuana.” Therefore, it is important for nurses to educate people about both the adverse health effects and legal ramifications of use as well as the potential therapeutic benefits linked to marijuana.[33].

The main psychoactive chemical in marijuana is Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). THC alters the functioning of the hippocampus and other areas of the brain that enable a person to form new memories and shift their attentional focus. As a result, marijuana causes impaired thinking and interferes with a person’s ability to learn and perform complicated tasks. THC also disrupts functioning of the cerebellum and basal ganglia that regulate balance, posture, coordination, and reaction time. For this reason, people who have used marijuana may not drive safely and may have problems playing sports or engaging in other physical activities.[34]

When marijuana is smoked, THC and other chemicals pass from the lungs into the bloodstream and are rapidly carried to the brain. The person begins to experience effects such as euphoria and sense of relaxation almost immediately. Other common effects include heightened sensory perception (e.g., brighter colors), laughter, altered perception of time, and increased appetite. Other people experience anxiety, fear, distrust, or panic, especially if they take too much, the marijuana has high potency, or the person is inexperienced in using cannabis. People who have taken large or highly potent doses of marijuana may experience acute psychosis, including hallucinations, delusions, and a loss of the sense of personal identity.[35].

If marijuana is consumed in foods or beverages, the effects are delayed for 30 minutes to 1 hour, because the drug must first pass through the digestive system. Eating or drinking marijuana delivers significantly less THC into the bloodstream. Because of the delayed effects, people may inadvertently consume more THC than they intend to.[36]. Although detectable amounts of THC may remain in the body for days or even weeks after use, the noticeable effects of smoked marijuana generally last from one to three hours, and marijuana consumed in food or drink may last for many hours.[37].

Delta-8 THC products are manufactured from hemp-derived cannabidiol (CBD) and have psychoactive and intoxicating effects similar to Delta-9 THC. Some Delta-8 THC products are labeled as “hemp products,” which can mislead consumers who associate “hemp” with being non-psychoactive. Delta-8 THC is available for purchase online and in stores but has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for safe use in any context. It should be kept out of reach of children and pets. Some manufacturers use unsafe chemicals to make Delta-8 THC through a chemical synthesis process that can contaminate the end product. As a result, there has been a recent increase in reports of adverse events with 8% of cases requiring admission to a critical care unit.[38]

THC affects brain systems that are still maturing through young adulthood, so regular use by teens may have negative and long-lasting effects on their cognitive development. Marijuana smoking is associated with large airway inflammation, increased airway resistance, lung hyperinflation, and chronic bronchitis. Vaping products that contain THC are associated with serious lung disease and death. Also, contrary to popular belief, marijuana can be addictive. THC stimulates neurons in the brain’s reward system to release higher levels of dopamine and encourages the brain to repeat the rewarding behavior.[39]

The potential medicinal properties of marijuana and THC have been the subject of research and heated debate for decades. THC itself has proven medical benefits in particular formulations. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of THC-based oral medications dronabinol (Marinol) and nabilone (Cesamet) for the treatment of nausea in clients undergoing cancer chemotherapy and to stimulate appetite in clients with wasting syndrome due to AIDS.[40] Marijuana is also used by individuals with certain illness such as multiple sclerosis for the management of spasticity, tics, convulsions, and dyskinesia.[41]

Sedative, Hypnotic, and Anxiolytic Misuse

Examples of medications in the sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic class include benzodiazepines, such as alprazolam (Xanax), diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), chlordiazepoxide (Librium), and clonazepam (Klonopin). An example of a hypnotic is zolpidem (Ambien). Although these are prescription medications, they are commonly misused.

Chronic use of benzodiazepines causes changes in the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, resulting in decreased GABA activity and the development of tolerance. When benzodiazepines are no longer present, or suddenly present at lower doses, withdrawal occurs.

Hallucinogen Misuse

In 2023, 8.8 million (3.1%) people in America aged 12 or older used hallucinogens.[42].Hallucinogens are a diverse group of drugs that alter a person’s awareness of their surroundings, as well as their own thoughts and feelings. They are commonly split into two categories: classic hallucinogens, such as LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, peyote, and N, N-dimethyltryptamine, know as DMT or ayahuasca, and dissociative drugs such as phencyclidine (PCP), ketamine, and dextromethorphan, an over-the-counter cough suppressant misused for its hallucinogenic and dissociative properties at high doses. PCP is an illegal drug that usually comes as a white powder that can be inhaled through the nose, injected into a vein, smoked, or swallowed.[43] Nonmedical use of dextromethorphan results in approximately 6,000 emergency department visits annually in the United States, often with co-ingestion of alcohol. Signs of toxic doses include neurobehavioral changes (e.g., hallucinations, inappropriate laughing, psychosis with dissociative features, agitation, and coma); tachycardia; dilated pupils; diaphoresis; and a “zombie-like” ataxic gait. Because acetaminophen is commonly present in cough and cold medications, toxic doses can cause severe delayed hepatotoxicity, hepatic failure, and death; serum acetaminophen levels should be obtained in all clients presenting with toxic levels of dextromethorphan.[44].

Hallucinogens cause hallucinations (sensations and images that seem real though they are not), and dissociative drugs can cause users to feel out of control or disconnected from their bodies and environments. Historically, some cultures have used hallucinogens like peyote as a part of religious or healing rituals. Users of hallucinogens and dissociative drugs have increased risk for serious harm because of altered perceptions and moods. As a result, users might do things they would never do when not under the influence of a hallucinogen, like jump off a roof or act on suicidal thoughts.[45]

Stimulant Misuse

Stimulants include amphetamine-type substances, cocaine, and crack. Stimulants cause the release of dopamine in the brain and are highly addictive because the flood of dopamine in the brain’s reward circuit strongly reinforces drug-taking behaviors. With continued drug use, the reward circuit adapts and becomes less sensitive to the drug. As a result, people take stronger and more frequent doses in an attempt to feel the same high and to obtain relief from withdrawal symptoms. Because the high from stimulants starts and fades quickly, people often take repeated doses in a form of binging, often giving up food and sleep while continuing to take the drug every few hours for several days. Both the use and withdrawal from amphetamines can cause psychosis with symptoms of hallucinations and paranoia.[46]

Methamphetamine comes in many forms and can be ingested by smoking, swallowing a pill, snorting, or injecting the powder that has been dissolved in water or alcohol. Methamphetamine can be easily made in small clandestine laboratories with relatively inexpensive over-the-counter ingredients such as pseudoephedrine, a common ingredient in cold medications. (To curb this illegal production, federal law requires pharmacies take steps to limit sales and obtain photo identification from purchasers.) Methamphetamine production also involves a number of other very dangerous chemicals. Toxic effects from these chemicals can remain in the environment long after the lab has been shut down, causing a wide range of health problems for people living in the area. These chemicals can also result in deadly lab explosions and house fires. Long-term use of methamphetamine has many negative consequences, including extreme weight loss, severe dental problems, intense itching leading to skin sores from scratching, involuntary movements (dyskinesia), anxiety, memory loss, and violent behavior[47].

Cocaine is another powerfully addictive stimulant drug made from the leaves of the coca plant native to South America. It is estimated that 9.7 million people aged 12 or older have used cocaine,.[48]. Users may snort cocaine powder through the nose, rub it into their gums, or dissolve the powder and inject it into the bloodstream. Cocaine that has been processed to make a rock crystal is called “crack.” The crystal is heated (making crackling sounds) to produce vapors that are inhaled into the lungs.https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cocaine, In the short-term, cocaine use can result in increased blood pressure, restlessness, and irritability. In the long-term, severe medical complications of cocaine use include heart attacks and seizures.[49]

Inhalant Misuse

In 2023, 2.6 million (0.9%) of people aged 12 or older in America used inhalants. Unlike other illicit drugs, the percentage of inhalant use was highest among adolescents aged 12 to 17.[50] Inhalants are various products easily bought or found in the home, such as spray paints, markers, glue, gasoline, and cleaning fluids. People who use inhalants breathe in the fumes through their nose or mouth, usually by sniffing, snorting, bagging, or huffing. Although the high that inhalants produce usually lasts just a few minutes, people often try to make it last by continuing to inhale again and again over several hours.[51]

Prescription medications can also be misused as inhalants. For example, amyl nitrate is a prescription medication administered via inhalation to relieve chest pain. However, it is misused by individuals to cause a high. It is referred to by the street drug of “poppers.

Risk Factors for Substance Misuse

Many factors influence the development of substance use disorders, including developmental, environmental, social, and genetic factors, and co-occurring mental health disorders. Other conditions called protective factors protect people from developing a substance use disorder or addiction. The relative influence of these factors varies across individuals and the life span.

Whether an individual ever uses alcohol or another substance and whether that initial use progresses to a substance use disorder of any severity depends on a number of factors including the following[52]:

- A person’s genetic makeup and biological factors

- The age when substance use begins

- Psychological factors related to a person’s unique history and personality

- Environmental factors, such as the availability of drugs, family and peer dynamics, financial resources, cultural norms, exposure to stress, and access to social support.

Early Life Experiences

Approximately 75% of adults admitted to treatment programs began substance misuse prior to the age of 17. Early life experiences can set the stage for substance use and sometimes escalate to substance use disorder. Early life stressors (referred to as adverse childhood experiences) include physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; neglect; household instability (such as parental substance use and conflict, mental illness, or incarceration of household members); and poverty. Adolescence is a critical vulnerable period for substance misuse and the development of substance use disorders because a characteristic of this developmental period is risk taking and experimentation. Additionally, the brain undergoes significant changes during this life stage, making it particularly vulnerable to substance exposure. Research shows that heavy drinking and drug use during adolescence affects development of the frontal cortex.[53]

Genetic and Molecular Factors

Genetic factors are thought to account for 40 to 70% of individual differences in risk for addiction. Although multiple genes are likely involved in the development of addiction, only a few specific gene variants have been identified that either predispose to or protect against addiction. Genes involved in strengthening the connections between neurons and in forming drug memories have also been associated with addiction risk. Like other chronic health conditions, substance use disorders are influenced by the complex interplay between a person’s genes and environment.[54]

Concurrent Mental Health Disorders

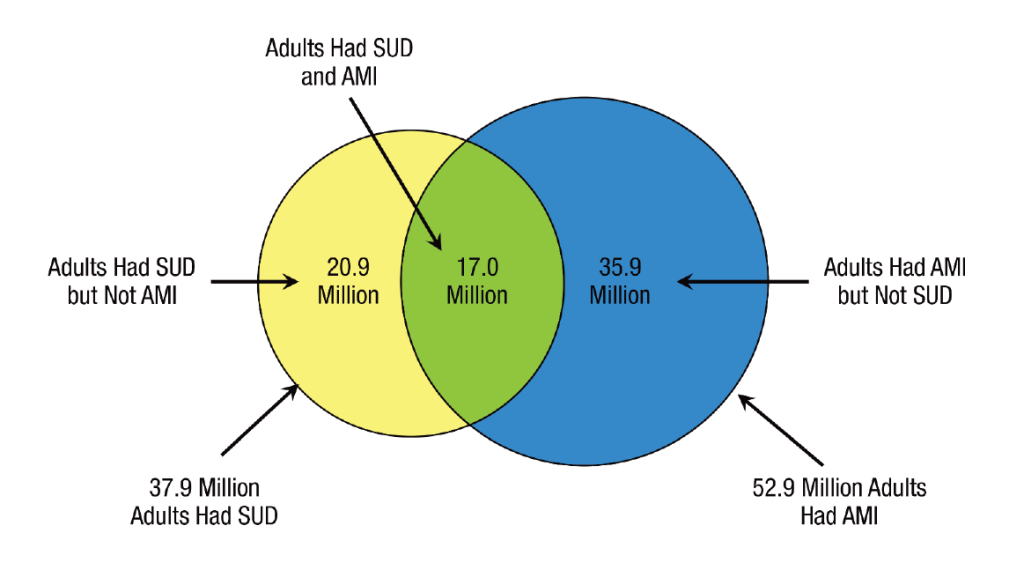

In 2020, 17 million adults (6.7%) had both a substance use disorder (SUD) and any mental health illness (AMI) as illustrated in Figure 14.5.[55] The relationship between SUDs and mental disorders is known to be bidirectional, meaning the presence of a mental health disorder may contribute to the development or exacerbation of an SUD, or an SUD may contribute to the development or exacerbation of a mental health disorder. The combined presence of SUDs and mental health disorders results in greater functional impairment; worse treatment outcomes; higher morbidity and mortality; increased treatment costs; and higher risk for homelessness, incarceration, and suicide.

The reasons why substance use disorders and mental health disorders often occur together are not clear, but there are three possible explanations. One reason may be because certain substances may temporarily mask the symptoms of mental health disorders (such as anxiety or depression). A second reason may be that certain substances trigger a mental health disorder that otherwise would not have developed. For example, research suggests that alcohol use increases risk for PTSD by altering the brain’s ability to recover from traumatic experiences. A third possible reason is that both substance use disorders and mental health disorders are caused by overlapping factors, such as particular genes, neurobiology, or exposure to traumatic or stressful life experiences.[56]

Mental health disorders and substance use disorders have overlapping symptoms, making diagnosis and treatment planning challenging. For example, people who use methamphetamine for a long period of time may experience paranoia, hallucinations, and delusions that can be mistaken for symptoms of schizophrenia.[57]

Gender

Some groups of people are more vulnerable to substance misuse and substance use disorders. For example, assigned males at birth (AMABs) tend to drink more than assigned females at birth (AFABs) and are at higher risk for alcohol use disorder. However, AFABs who use cocaine, opioids, or alcohol may progress from initial use to a substance use disorder faster than AMABs. Compared with AMABs, AFABs also exhibit greater withdrawal symptoms from some drugs such as nicotine and have higher levels of the stress hormone cortisol.[58]

Race and Ethnicity

Neurobiological factors contributing to differential rates of substance use disorders across racial and ethnic groups have been researched. A study using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) found that African American smokers showed greater activation of the prefrontal cortex upon exposure to smoking-related cues than did Caucasian smokers, an effect that may partly contribute to the lower smoking-cessation success rates among African Americans.[59]

Alcohol research on racial and ethnic groups has shown that approximately 36% of East Asians carry a gene variant that alters the rate of alcohol metabolism, causing a buildup of acetaldehyde, a toxic by-product that produces symptoms such as flushing, nausea, and rapid heartbeat. Although these effects may protect some individuals of East Asian descent from alcohol use disorder, those who drink despite the effects are at increased risk for esophageal and head and neck cancers.[60]

Individual, Family, and Community Level Risk Factors

An individual’s risk factors for developing SUD include the following[61]:

- Early initiation of substance use: Engaging in alcohol or drug use at a young age

- Early and persistent problem behavior: Emotional distress, aggressiveness, and “difficult” temperaments in adolescents

- Rebelliousness: High tolerance for deviance and rebellious activities

- Favorable attitudes toward substance use: Positive feelings towards alcohol or drug use; low perception of risk

- Peer substance use: Friends and peers who engage in alcohol or drug use

- Genetic predictors: Genetic susceptibility to alcohol or drug use

- Academic failure beginning in late elementary school: Poor grades in school

- Lack of commitment to school: When a young person no longer considers the role of being a student as meaningful and rewarding or lacks investment or commitment to school

Risk factors at the family level for an individual developing SUD are as follows[62]:

- Family management problems: Poor parental management practices, including failure to set clear expectations for children’s behavior, failure to supervise and monitor children, and excessively harsh or inconsistent punishment

- Family conflict: Conflict between parents or between parents and children, including abuse or neglect

- Favorable parental attitudes: Parental attitudes that are favorable to drug use and parental approval of drinking and drug use

- Family history of substance misuse: Persistent or generalized substance misuse by family members

These are the risk factors at the community level for individuals developing SUD[63]:

- Low cost of alcohol: Low alcohol sales tax, happy hour specials, and other price discounting

- High availability of substances: High number of alcohol outlets in a defined geographical area or per a sector of the population

- Community laws and norms favorable to substance use: Community reinforcement of norms suggesting alcohol or drug use is acceptable for youth

- Low neighborhood attachment: Low level of bonding to the neighborhood

- Community disorganization: Living in neighborhoods with high population density, lack of public places, physical deterioration, or high rates of adult crime

- Low socioeconomic status: Parents’ low socioeconomic status, as measured through a combination of education, income, and occupation

- Transitions and mobility: Communities with high rates of mobility within or between communities

- Media portrayal of alcohol use: Exposure to actors using alcohol or drugs in movies or television

Prevention of Substance Misuse

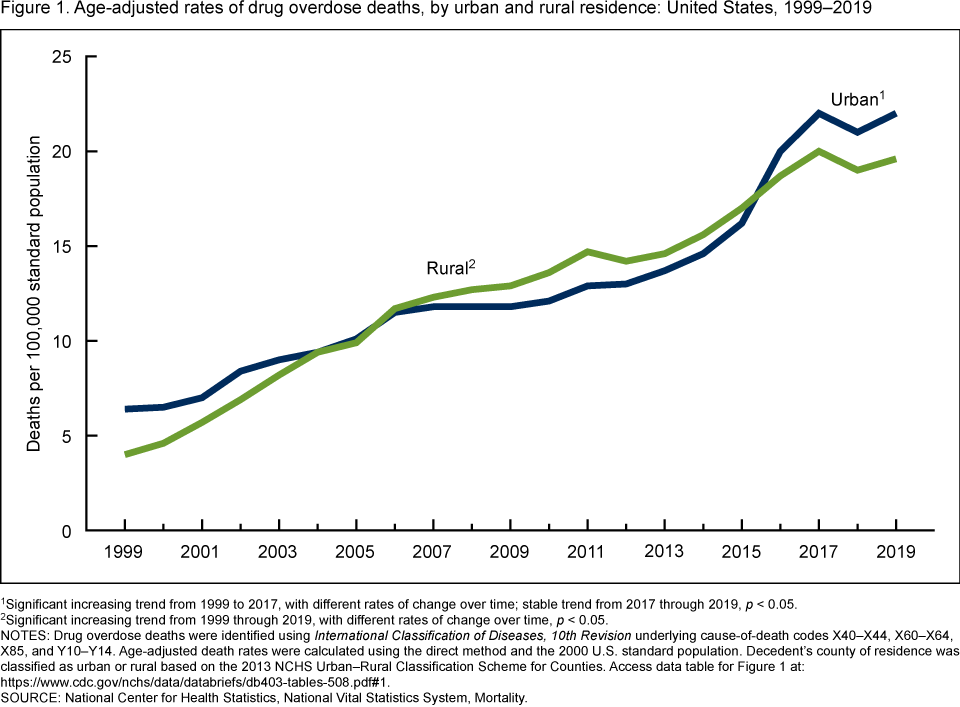

The misuse of alcohol and drugs and substance use disorders has a significant impact on public health in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports over 100,000 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States in 2021, and overdose deaths in urban and rural populations have shown a significant upward trend over the past 20 years.[64] See Figure 14.8[65] for a graphic of overdose rates in urban and rural areas.

Substance misuse is associated with a wide range of health and social problems, including heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, various cancers (e.g., liver, lung, and colon cancer), mental health disorders, neonatal abstinence syndrome, driving under the influence (DUI) injuries and fatalities, incarcerations, sexual assaults and rapes, unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, and bloodborne pathogens like hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[66] Given the impact of substance misuse on public health, it is critical to implement preventative interventions to stop substance misuse from starting, as well as to identify and intervene early with individuals who have already begun to misuse substances.

Promoting Protective Factors

Experiencing a family member’s substance use disorder is considered an adverse childhood event (ACE) that can impact a child’s risk for developing behavioral problems, substance misuse, and chronic illness. Targeted prevention programs implemented at the family, school, and individual levels can complement broader population-level policies by promoting protective factors for children and adolescents.

Protective factors help prevent substance use disorders from developing despite the presence of risk factors. Protective factors exist at the individual, family, school, and community levels.

Examples of interventions to promote protective factors at the individual level include the following[67]:

- Social, emotional, and behavioral competence: Promoting interpersonal skills that help youth integrate feelings, thoughts, and actions to achieve specific social and interpersonal goals.

- Self-efficacy: Enhancing an individual’s belief that they can modify, control, or abstain from substance use.

- Spirituality: Supporting beliefs in a higher being or involvement in spiritual practices or religious activities.

- Resiliency: Encouraging an individual’s capacity for adapting to change and coping with stressful events in healthy and flexible ways.

Interventions to promote protective factors at the family, school, and community levels are as follows[68]:

- Opportunities for positive social involvement: Creating developmentally appropriate opportunities to be meaningfully involved with the family, school, or community.

- Recognition for positive behavior: Providing community and family recognition of individuals’ efforts and accomplishments to encourage positive future behaviors.

- Bonding: Promoting attachment, commitment, and positive communication with family members, schools, and communities.

- Marriage or committed relationships: Encouraging committed relationships with people who do not misuse alcohol or drugs.

- Healthy beliefs and standards for behavior: Establishing family, school, and community norms that communicate clear and consistent expectations about not misusing alcohol or drugs.

Prevention Interventions

The Institute of Medicine describes three categories of prevention interventions: universal, selective, and indicated. Universal interventions are aimed at all members of a given population, selective interventions are aimed at a subgroup determined to be at high-risk for substance use, and indicated interventions are targeted for individuals who are already misusing substances but have not developed a substance use disorder. Examples of evidence-based prevention interventions for each category are provided in the following subsections.

Universal Interventions

Universal interventions include policies that affect the entire population, such as the setting the minimum legal drinking age or reducing the availability of substances in a community. For example, laws targeting alcohol-impaired driving, such as license revocation for impaired driving and 0.08 legal blood alcohol (BAC) limits have helped cut alcohol-related traffic deaths per 100,000 in half since the early 1980s.[69]

Several family-focused, universal prevention interventions show substantial preventive effects on substance use. One example is the Strengthening Families Program (SFP)[70]: A widely used seven-session, this family-focused program enhances parenting skills, such as nurturing, setting limits, and communicating, as well as promoting adolescents’ skills in refusing substances. Across multiple studies conducted in rural United States communities, SFP showed reductions in tobacco, alcohol, and drug use up to 9 years after the intervention (i.e., to age 21) compared with youth who were not assigned to the SFP. SFP also shows reductions in prescription drug misuse up to 13 years after the intervention (i.e., to age 25). Strong African American Families, a cultural adaptation of SFP, shows reductions in early initiation and rate of alcohol use for Black or African American rural youth.

Selective Interventions

Selective interventions are delivered to particular communities, families, or children who, due to exposure to risk factors, are at increased risk of substance misuse problems. Target audiences may include families living in poverty, the children of substance-misusing parents, or children who have difficulties with social skills. Selective interventions deliver specialized prevention services to individuals with the goal of reducing identified risk factors, increasing protective factors, or both. Examples of selective intervention programs are the Nurse-Family Partnership, Familias Unidas, and Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students[71]:

- Nurse-Family Partnership : A program focused on children younger than age 5 has shown significant reductions in the use of alcohol in the teen years compared with those who did not receive the intervention. Trained nurses provide an intensive home visitation intervention for at-risk, first-time mothers during pregnancy. This intervention provides ongoing education and support to improve pregnancy outcomes, infant health, and development of parenting skills.[72] For an example of a program, see casadelosninos.org/programs-and-resources/nurse-family-partnership/.

- Familias Unidas[73]: A family-based intervention for Hispanic or Latino youth that includes both multi-parent groups (8 weekly 2-hour sessions) and 4 to 10 1-hour individual family visits. It has been shown to lower substance use or delay the start of substance use among adolescents.[74]

- Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS)[75]: A brief motivational intervention designed to help students reduce alcohol misuse and negative consequences of their drinking. It consists of 2 1-hour interviews with a brief online assessment after the first session. The first interview gathers information about alcohol consumption patterns and personal beliefs about alcohol while providing instructions for self-monitoring drinking between sessions. The second interview uses data from the online assessment to develop personalized, normative feedback that reviews negative consequences and risk factors, clarifies perceived risks and benefits of drinking, and provides options for reducing alcohol use and its consequences. Follow-up studies of students who used BASICS have shown reductions in the quantity of drinking in the general college population, as well as fraternity members.

Indicated Prevention Interventions

Indicated prevention interventions are directed to those who are already involved in substance misuse but who have not yet developed a substance use disorder. An example of an indicated prevention intervention is Coping Power, a 16-month program for children in Grades 5 and 6.[76] The program uses skills-based training to increase social competence, self-regulation, and positive parental involvement. Results include reduced substance use, delinquency, and aggressive behaviors.[77]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). The Controlled Substance Act. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/csa ↵

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration. (n.d.). The Controlled Substance Act. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/csa ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2022). Drugs, brains, and behavior: The science of addiction treatment and recovery. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/treatment-recovery ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 national survey on drug use and health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse, & Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- NCSBN (n.d.). Substance use disorder in nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/nursing-regulation/practice/substance-use-disorder/substance-use-in-nursing.page ↵

- NCSBN (n.d.). Substance use disorder in nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/nursing-regulation/practice/substance-use-disorder/substance-use-in-nursing.page ↵

- Nyhus, J. (2021). Drug diversion in healthcare. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/drug-diversion-in-healthcare/ ↵

- NCSBN (n.d.). Substance use disorder in nursing. https://www.ncsbn.org/nursing-regulation/practice/substance-use-disorder/substance-use-in-nursing.page ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2019, May). Methamphetamine drugfacts. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/methamphetamine ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- “NIH_standard_drink_comparison.jpg” by National Institutes of Health is in the Public Domain ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2023). National survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases/2023#companion-infographic-reports ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2023). National survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases/2023#companion-infographic-reports ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2023). National survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases/2023#companion-infographic-reports ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2022. Opioid intoxication; [updated 2022, February 18]. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000948.htm ↵

- “3-waves-2019-medium.PNG” by The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/understanding-the-opioid-overdose-epidemic.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, November 1). Understanding the opioid overdose epidemic. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/understanding-the-opioid-overdose-epidemic.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, April 2). Fentanyl facts. Centers for Disease Control. https://www.cdc.gov/stop-overdose/caring/fentanyl-facts.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, September 4). Overdose deaths and the involvement of illicit drugs. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://archive.cdc.gov/#/details?url=https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/featured-topics/VS-overdose-deaths-illicit-drugs.html ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2023). National survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases/2023#companion-infographic-reports ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2022, May 4). 5 things to know about Delta-8 tetrahydrocannabinol - Delta-8 THC. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/5-things-know-about-delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol-delta-8-thc ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cannabis (Marijuana). https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cannabis-marijuana ↵

- Shepard, S. (2021, December 6). Can medical marijuana help your MS? WebMD. https://www.webmd.com/multiple-sclerosis/multiple-sclerosis-medical-marijuana#:~:text=Surveys%20show%20that%20many%20people%20with%20MS%20already,that%20attacks%20your%20brain%2C%20spinal%20cord%2C%20and%20nerves. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2023). National survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases/2023#companion-infographic-reports ↵

- A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): A.D.A.M., Inc.; c1997-2022. Substance use - phencyclidine (PCP); [updated 2022, February 18].https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000797.htm#:~:text=Phencyclidine%20(PCP)%20is%20an%20illegal,into%20a%20vein%20(shooting%20up) ↵

- Journey, J.D., Agrawal, S., & Stern, E. (2023, June 26). Dextromethorphan toxicity. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538502/ ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2021, November). Hallucinogens drugfacts. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/hallucinogens ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (n.d.) Drugs A to Z: Methamphetamine. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/drugs-a-to-z#M ↵

- Yasaei, R. & Saadabadi, A. (2023, May 1). Methamphetamine. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publications. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535356/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2023). National survey on drug use and health. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases/2023#companion-infographic-reports ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (n.d.). Cocaine. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/cocaine ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2024, September). Inhalants. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/inhalants ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2024, September). Inhalants. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/inhalants ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Image is a derivative of “Past Year Substance Abuse Disorder (SUD) and Any Mental Illness (AMI): Among Adults Aged 18 or Older; 2020” table by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Used under Fair Use. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-nsduh-annual-national-report. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2021, November 21). Drug overdose deaths in the U.S. top 100,000 annually [Press Release]. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm ↵

- “db403-fig1.png” from by Hedegaard, H., & Spencer, M. R. is in the Public Domain. Access the full report at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db403.htm#fig1. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Strengthening Families Program by Dr. Karol Kumfer. (2025). https://strengtheningfamiliesprogram.org ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse. (n.d.). Familias Unidas. https://preventionservices.acf.hhs.gov/programs/793/show ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development. (n.d.). Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS). https://www.blueprintsprograms.org/brief-alcohol-screening-and-intervention-for-college-students-basics ↵

- www.copingpower.com/Brochure.pdf. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

A psychoactive compound with the potential to cause health and social problems, including substance use disorder.

The use of any of the psychoactive substances.

Substances regulated by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency.

When a person suddenly stops using a drug, their body goes through withdrawal, a group of physical and mental symptoms that can range from mild to life-threatening.

A group of physical and mental symptoms that can range from mild to life-threatening.

The use of alcohol or drugs in a manner, situation, amount, or frequency that could cause harm to the user or to those around them.

A disturbance in behavior or mental function during or after the consumption of a substance.

The biological response of the human body when too much of a substance is ingested.

An illness caused by repeated misuse of substances such as alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants (amphetamines, cocaine, and other stimulants), and tobacco.

Associated with compulsive or uncontrolled use of one or more substances.

The return to substance use after a significant period of abstinence.

A process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.

Individuals with severe substance use disorders can overcome their disorder with effective treatment and regain health and social function.

When medication is redirected from its intended destination for personal use, sale, or distribution to others.

Excessive behaviors related to gambling, viewing pornography, compulsive sexual activity, Internet gaming, overeating, shopping, overexercising, and overusing mobile phone technologies.

Defined as 14 grams (0.6 ounces) of pure alcohol.

A female consuming 8 or more drinks per week and a male consuming 15 or more standard drinks per week, or either gender binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past 30 days.

Defined as a pattern of alcohol consumption that brings the blood alcohol concentration level to 0.08% or more.