14.5 Management of Overdose, Detoxification, and Withdrawal

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Nurses commonly provide care for patients who are intoxicated or receiving withdrawal treatment for alcohol, opioids, or other substances. Furthermore, patients frequently underreport alcohol and substance use, so nurses must be aware of signs of withdrawal in patients receiving medical care for other issues and notify the health care providers.[1]

Withdrawal management, also called detoxification, includes interventions aimed at managing the physical and emotional symptoms that occur after a person suddenly stops using a psychoactive substance. Withdrawal symptoms vary in intensity and duration based on the substance(s) used, the duration and amount of use, and the overall health of the individual. Some substances, such as opioids, sedatives, and tranquilizers, produce significant physical withdrawal effects, especially if they have been used in combination with heavy alcohol use. Rapid or unmanaged cessation from these substances can result in longer than expected course of withdrawal with seizures and other health complications. Assessment and treatment of alcohol withdrawal and opioid withdrawal symptoms will be further discussed in the following sections.

Alcohol Overdose and Withdrawal

Alcohol Overdose

An alcohol overdose occurs when there is so much alcohol in the bloodstream that areas of the brain controlling autonomic nervous system functions (e.g., breathing, heart rate, and temperature control) begin to shut down. Signs of alcohol overdose include mental confusion, difficulty remaining conscious, vomiting, seizures, trouble breathing, slow heart rate, clammy skin, dulled gag reflex, and extremely low body temperature. Alcohol intoxication while also taking opioids or sedative-hypnotics (such as benzodiazepines or sleep medications) increases the risk of an overdose. Alcohol overdose can cause permanent brain damage or death.[2]

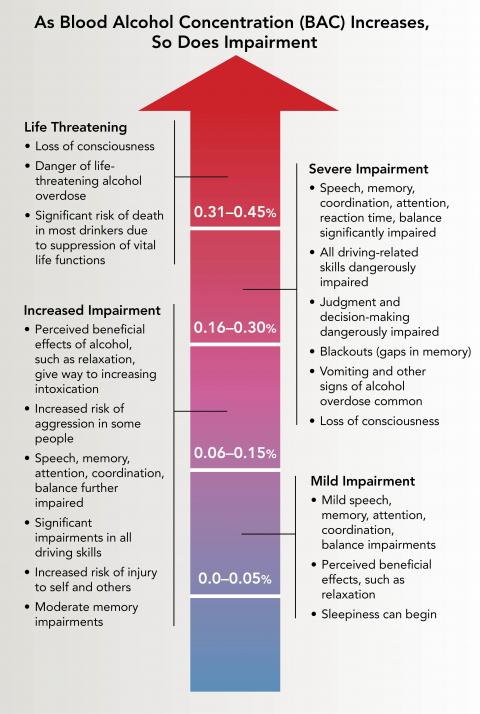

Anyone who consumes too much alcohol too quickly is in danger of an alcohol overdose, especially for individuals who engage in binge drinking. As blood alcohol concentration (BAC) increases, so does the risk of harm. When BAC reaches high levels, blackouts (gaps in memory), loss of consciousness (passing out), and death can occur. BAC can continue to rise even when a person stops drinking or is unconscious because alcohol in the stomach and intestine continues to enter the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body. See Figure 14.2c[3] for the impairments related to rising BAC.

It is dangerous to assume that a person who drank an excessive amount of alcohol will “sleep it off.” One potential danger of alcohol overdose is choking on one’s vomit and dying from lack of oxygen because high levels of alcohol intake hinder the gag reflex, resulting in the inability to protect the airway. Asphyxiation can occur due to an obstructed airway or from aspiration of gastric contents into the lungs. For this reason, do not leave a person alone who has passed out due to alcohol misuse. Keep them in a partially upright position or roll them onto one side with an ear toward the ground to prevent choking if they begin vomiting.[4] Critical signs and symptoms of an alcohol overdose include the following[5]:

- Mental confusion or stupor

- Difficulty remaining conscious or inability to wake up

- Vomiting

- Seizures

- Slow respiratory rate (fewer than 8 breaths per minute)

- Irregular breathing (10 seconds or more between breaths)

- Slow heart rate

- Clammy skin

- No gag reflex

- Extremely low body temperature

- Bluish skin color or paleness

If there is suspicion that someone has overdosed on alcohol, seek emergency assistance or call 911. While waiting for help to arrive, be prepared to provide information to the responders, such as the type and amount of alcohol the person drank and any other drugs they ingested, current medications, allergies to medications, and any existing health conditions.[6]

Medical Treatment of Acute Alcohol Intoxication

Acute alcohol intoxication can cause hypotension and tachycardia as a result of peripheral vasodilation or fluid loss. Treatment begins with the evaluation of the individual’s blood alcohol level (BAC). It is important to know if other drugs like opioids, benzodiazepines, or illicit drugs have been ingested because this increases the risk of overdose, and other treatments (such as naloxone) may be required. For patients with moderate to severe intoxication, routine lab work includes serum glucose and electrolytes to assess for hypoglycemia, hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, and hyperlactatemia. If hypoglycemia is present, a dextrose intravenous infusion is provided. Severely intoxicated clients may receive intravenous thiamine, along with dextrose, to prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Wernicke’s encephalopathy is an acute, life-threatening neurological condition characterized by nystagmus, ataxia, and confusion caused by thiamine (B1) deficiency associated with alcohol use disorder[7].

Some patients with acute alcohol intoxication can become agitated, violent, and uncooperative. Chemical sedation with administration of benzodiazepines may be required to prevent the client from harming themselves or others. However, benzodiazepines must be used with caution because they worsen the respiratory depression caused by alcohol. Acute alcohol intoxication may require placement in an intensive care unit. Risk factors for admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) include abnormal or unstable vital signs (hypotension, tachycardia, fever, or hypothermia), hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and the need for parenteral sedation. If the client has inadequate respirations or airway maintenance, intubation and mechanical ventilation are required. Activated charcoal and gastric lavage are generally not helpful because of the rapid rate of absorption of alcohol from the gastrointestinal tract. Some acutely intoxicated clients experience head traumas due to severe intoxication from injuries sustained while intoxicated. If the client’s mental status does not improve as their BAC level decreases, a CT scan of the head may be obtained.[8]

The prevalence of alcohol use disorder is estimated to be as high as 40% among hospitalized patients. Nurses on any unit within a hospital can expect to see patients with alcohol use disorder. Approximately half of patients experience alcohol withdrawal when they reduce or stop drinking, with as many as 20% experiencing serious manifestations such as hallucinations, seizures, and delirium tremens.[9] Severe alcohol withdrawal is considered a medical emergency that is best managed in an intensive care unit.

Symptoms of early or mild alcohol withdrawal include anxiety, minor agitation, restlessness, insomnia, tremor, diaphoresis, palpitations, headache, and alcohol craving. Patients often experience loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Their risk for falls often increases when they try to go unassisted to the bathroom with these gastrointestinal symptoms. Physical signs include sinus tachycardia, systolic hypertension, hyperactive reflexes, and tremor. Without treatment, symptoms of mild alcohol withdrawal generally begin within 6 to 36 hours after the last drink and resolve within 1 to 2 days.[10]

Some clients develop moderate to severe withdrawal symptoms that can last up to 6 days, such as withdrawal hallucinations, seizures, or delirium tremens:

- Hallucinations typically occur within 12 to 48 hours after the last drink. They are typically visual and commonly involve seeing insects or animals in the room, although auditory and tactile phenomena may also occur.[11]

- Alcohol withdrawal-related seizures can occur within 6 to 48 hours after the last drink. Risk factors for seizures include concurrent withdrawal from benzodiazepines or other sedative-hypnotic drugs.[12]

- Delirium tremens (DTs) is a rapid-onset, fluctuating disturbance of attention and cognition that is sometimes associated with hallucinations. In its most severe manifestation, DTs are accompanied by agitation and signs of extreme autonomic hyperactivity, including fever, severe tachycardia, hypertension, and drenching sweats. DTs typically begin between 48 and 96 hours after the client’s last drink. Mortality rates from withdrawal delirium have been historically as high as 20%, but with appropriate medical management, the mortality rate is between 1 and 4%. Death is attributed to cardiovascular complications, hyperthermia, aspiration, and severe fluid and electrolyte disorders.[13]

Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale (CIWA-Ar)

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Scale (CIWA-Ar) is the most widely used scale to determine the need for medically supervised withdrawal management. It is used in a wide variety of settings, including outpatient, residential, emergency, psychiatric, and general medical-surgical units when there is a clinical concern regarding a client’s alcohol withdrawal.

The CIWA-Ar scale is typically utilized in association with a protocol containing medications to guide symptom-triggered treatment. Patients with an alcohol use disorder who have a CIWA-Ar score of less than 10 do not typically require medical management.[14]

There are ten questions on the CIWA-Ar related to nausea/vomiting, tremor, paroxysmal sweats, anxiety, agitation, tactile disturbances, auditory disturbances, visual disturbances, headache, and level of orientation. The questions are rated from 0 to 7, except for orientation that is rated from 0 to 4. View the full CIWA-Ar scale in the following box.

View the CIWA-Ar on the MDCalc medical reference website.

Treatment of Alcohol Withdrawal

Benzodiazepines are used to treat the psychomotor agitation most patients experience during alcohol withdrawal and prevent progression from minor symptoms to severe symptoms of seizures, hallucinations, or delirium tremens. Diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan), and chlordiazepoxide (Librium) are used most frequently to treat or prevent alcohol withdrawal symptoms.[15]

Anticonvulsants may be used concurrently or instead of benzodiazepines. Anticonvulsants decrease the probability of withdrawal seizures. Examples include carbamazepine (Tegretol), valproate (Depakote), and gabapentin (Neurontin).

Chronic alcohol use is associated with depletion of thiamine and magnesium. Patients receiving alcohol withdrawal treatment typically receive intravenous thiamine, along with dextrose, to prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy. [16] If untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can progress to Korsakoff’s syndrome, a chronic, irreversible memory disorder resulting from thiamine deficiency.[17] Treatment of other electrolyte deficiencies may be included during alcohol withdrawal treatment.

Opioid Overdose and Withdrawal

Treating Opioid Overdose

Opioid intoxication causes problematic behavioral or psychological changes such as initial euphoria followed by apathy, dysphoria, psychomotor retardation or agitation, and impaired judgment. These are some signs of opioid intoxication[18][19]:

- Pupillary constriction (or dilation from severe overdose)

- Drowsiness or coma

- Slurred speech

- Impairment in attention or memory

Naloxone reverses the effects of an opioid overdose. A single-step nasal spray delivery of naloxone is the easiest and most successful route of administration for members of the community and first responders. Naloxone intramuscular injection is also available.[20] Five basic steps are recommended for nurses, first responders, health professionals, and other bystanders to rapidly recognize and treat opioid overdose to prevent death.[21]

- Recognize Signs of Opioid Overdose

- Signs of opioid overdose include the following:

- Unconsciousness or inability to awaken

- Pinpoint pupils

- Slow, shallow breathing; breathing difficulty manifested by choking sounds or a gurgling/snoring noise from a person who cannot be awakened; or respiratory arrest

- Fingernails or lips turning blue or purple

- If an opioid overdose is suspected, try to stimulate the person by calling their name or vigorously grinding one’s knuckles into their sternum.

- Signs of opioid overdose include the following:

- Obtain Emergency Assistance: If the person does not respond, call 911 or obtain emergency assistance.

- Provide Rescue Breathing, Chest Compressions, and Oxygen As Needed[22]

- Provide rescue breathing if the person is not breathing on their own. A barrier device is recommended to reduce the risk of disease transmission. Rescue breathing for adults involves the following steps:

- Be sure the person’s airway is clear.

- Place one hand on the person’s chin, tilt the head back, and pinch the nose closed.

- Place your mouth over the person’s mouth to make a seal and give two slow breaths.

- Watch for the person’s chest (but not the stomach) to rise.

- Follow up with one breath every five seconds.

- If the individual becomes pulseless, provide cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- Administer oxygen as needed.

- Provide rescue breathing if the person is not breathing on their own. A barrier device is recommended to reduce the risk of disease transmission. Rescue breathing for adults involves the following steps:

- Administer the First Dose of Naloxone[23]

- Naloxone should be administered to anyone suspected of an opioid overdose.

- Research has shown that women, older adults, and those without obvious signs of opioid use disorder are undertreated with naloxone and, as a result, have a higher death rate. Therefore, naloxone should be considered for women and the elderly who are found unresponsive.

- Naloxone can be used in life-threatening opioid overdose circumstances in pregnant women.

- Naloxone can be given intranasally, intramuscularly, subcutaneously, or intravenously. The nasal spray is a prefilled device that requires no assembly and delivers a single dose into one nostril. An auto-injector is injected into the outer thigh to deliver naloxone intramuscularly or subcutaneously.

- All naloxone products are effective in reversing opioid overdose, including fentanyl-involved opioid overdoses, although overdoses involving potent or large quantities of opioids may require additional doses of naloxone.

- Withdrawal triggered by naloxone can feel unpleasant; some people may awaken confused, agitated, or aggressive. Provide safety, reassurance, and explain what is happening.

- Administer a Second Dose of Naloxone If the Person Does Not Respond[24]:

- If the person overdosing does not respond within 2 to 3 minutes after administering a dose of naloxone, administer a second dose of naloxone.

- People who have taken long-acting or potent opioids (like fentanyl) may require additional intravenous bolus doses or an infusion of naloxone.

- The duration of effect of naloxone depends on dose, route of administration, and overdose symptoms. It is shorter than the effects of some opioids, so a second dose may be required.

- Monitor the Person’s Response[25]:

- Most people respond to naloxone by returning to spontaneous breathing within 2 to 3 minutes. Continue resuscitation while waiting for the naloxone to take effect.

- The goal of naloxone therapy is to restore adequate spontaneous breathing but not necessarily achieve complete arousal.

- The individual should be monitored for recurrence of signs and symptoms of opioid toxicity for at least four hours from the last dose of naloxone. People who have overdosed on long-acting opioids like fentanyl require prolonged monitoring.

- Because naloxone has a relatively short duration of effect, overdose symptoms may return. Therefore, it is essential to get the person to an emergency department or other source of medical care as quickly as possible, even if the person revives after the initial dose of naloxone and seems to feel better.

Medically supervised opioid withdrawal, also known as detoxification, involves administering medication to reduce the severity of withdrawal symptoms that occur when an opioid-dependent patient stops using opioids. However, supervised withdrawal alone does not generally result in sustained abstinence from opioids, nor does it address reasons the patient became dependent on opioids.[26]

Patients may undergo detoxification for several reasons[27]:

- Initiating the process to “get clean and stay clean” from opioids. Some patients may follow up with inpatient, residential, or outpatient treatment after completing the detoxification process.

- Treating withdrawal symptoms when a patient dependent on opioids or heroin becomes hospitalized and lacks access to the misused substance.

- Beginning the first step in treating opioid use disorder and transitioning to medication-assisted treatment like methadone or suboxone treatment.

- Establishing an abstinent state without withdrawal symptoms required for the patient’s setting or status (e.g., incarceration, probation, or a drug-free residential program).

Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale

The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) is used in both inpatient and outpatient settings for the monitoring of withdrawal symptoms during opioid detoxification. It can be serially administered to track changes in the severity of withdrawal symptoms over time or in response to treatment.[28] Symptoms of opioid withdrawal include drug craving, anxiety, restlessness, gastrointestinal distress, diaphoresis, and tachycardia. COWS rates the severity of 11 signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal on a scale from 0 to 5, as described in the following box.

View the COWS on the MedCalc medical reference website.

Treatment of Opioid Withdrawal

A calm, quiet environment with supportive and reassuring staff is instrumental for helping patients overcome most symptoms of acute opioid withdrawal and can decrease the need for pharmacologic interventions. Patients who have associated diarrhea, vomiting, or sweating should be monitored for dehydration and have fluid levels maintained with oral and/or intravenous fluids.[29] Medications used to treat withdrawal symptoms include opioid agonists such as buprenorphine and methadone, as well as Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists such as clonidine and lofexidine. Other medications may be prescribed to treat specific symptoms.[30]

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is an effective treatment for opioid withdrawal symptoms. Buprenorphine is a synthetic opioid developed in the late 1960s and is used to treat pain and opioid use disorder. This drug is a synthetic analog of thebaine—an alkaloid compound derived from the poppy flower. Buprenorphine is categorized as a Schedule III drug, which means it has a moderate-to-low potential for physical dependence or a high potential for psychological dependence. Buprenorphine is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat acute and chronic pain and opioid dependence. This drug is used in agonist substitution treatment—a method for addressing addiction by substituting a more potent full agonist opioid, such as heroin, with a less potent opioid, such as buprenorphine or methadone. A disadvantage of buprenorphine is it can worsen opioid withdrawal symptoms if not administered carefully. To avoid this situation, the client must be in a state of mild to moderate withdrawal before receiving their first dose of buprenorphine (i.e., have a COWS score greater than 10). The first dose of buprenorphine is typically 2 to 4 mg sublingually. Long-acting injectable formulations are available for patients who have successfully used the sublingual form. [31] www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459126/Buprenorphine can cause respiratory depression. Common side effects include sedation, headache, nausea, constipation, and insomnia.[32]

Buprenorphine/Naloxone

The combination medication buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone) is used for detoxification, as well as maintenance of abstinence from opioids. The addition of naloxone, an opioid blocker, is useful to prevent misuse of buprenorphine. If the combination is misused, for example injecting it instead of sublingual use, the naloxone is activated and will negate the opioid effects of buprenorphine. It may be used in outpatient settings.[33]

Methadone

Methadone is a long-acting, synthetic opioid that reduces opioid craving and withdrawal symptoms by blocking the effect of opioids. It is typically prescribed in one of two ways[34]:

- Substitution Therapy: Methadone is prescribed to replace the use of an opioid and then is gradually tapered to prevent severe withdrawal symptoms.

- Maintenance Therapy: It is prescribed long-term as a one component of a comprehensive medication-assisted treatment plan for opioid use disorder. With counseling and other behavioral therapies, methadone helps individuals achieve and sustain recovery and lead active and meaningful lives.

In contrast to buprenorphine, methadone does not induce withdrawal symptoms when administered to a patient with opioid in their system because it has an additive effect on opioids that are already present.[35]

A typical dose of methadone on Day 1 of withdrawal treatment varies from 10-20 mg orally. Injections are only recommended for patients unable to take oral medication. Dosing is titrated to control withdrawal symptoms while avoiding oversedation and motor impairment. Common side effects of methadone include constipation, mild drowsiness, excess sweating, peripheral edema, and erectile dysfunction.[36]

Due to its long half-life, patients are at risk for overdose if the dose is titrated up too quickly or their starting dose is too high for their tolerance level of opioids. Overdose with methadone can be lethal due to arrhythmia or respiratory depression. It is treated with naloxone with repeated doses as needed and rapid transfer to a medical unit.[37]

Alpha-2 Adrenergic Agonists

Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, including clonidine and lofexidine, decrease many symptoms of opioid withdrawal and effectively relieve the autonomic symptoms of sweating, diarrhea, intestinal cramps, nausea, anxiety, and irritability. They are least effective for symptoms of myalgias, restlessness, insomnia, and craving.[38]

Clonidine can be taken orally or administered via a clonidine patch and changed weekly. Relief from withdrawal symptoms typically occurs within 30 minutes after a dose. However, common side effects of hypotension and sedation limit the use of these drugs. Contraindications to Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists include hypotension, renal insufficiency, cardiac instability, pregnancy, and psychosis. Tricyclic antidepressants should be stopped three weeks prior to use.[39]

Symptom-Specific Medications

Various medications are prescribed to provide targeted relief for symptoms of opioid withdrawal[40]:

- Anxiety, irritability, restlessness: Diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, lorazepam, and clonazepam

- Abdominal cramping: Dicyclomine

- Diarrhea: Bismuth and loperamide

- Nausea/vomiting: Ondansetron, prochlorperazine, and promethazine

- Insomnia: Trazodone, doxepin, mirtazapine, quetiapine, and zolpidem

- Muscle aches, joint pain, and headache: Ibuprofen, acetaminophen, ketorolac, and naproxen

- Muscle spasms and restless legs: Cyclobenzaprine, baclofen, diazepam, and methocarbamol

Warm baths, rehydration, and gentle stretching are also helpful for relieving muscle aches and cramps. Use of benzodiazepines and zolpidem is not recommended for clients receiving methadone or buprenorphine therapy unless they are under close medical supervision due to the risk of oversedation.[41]

Cannabis Intoxication and Withdrawal

Cannabis intoxication is defined as problematic behavior or psychological changes (e.g., impaired motor coordination, euphoria, anxiety, sensation of slowed time, impaired judgment, social withdrawal) that developed during or shortly after cannabis use. Signs and symptoms of cannabis intoxication include the following[42]:

- Enlarged conjunctival vessels

- Increased appetite

- Dry mouth

- Tachycardia

According to the CDC, a fatal overdose caused solely by marijuana is unlikely. However, effects from marijuana can lead to unintentional injury, such as a motor vehicle crash, fall, or poisoning. Overconsumption of marijuana can occur when using marijuana-infused products like edibles and beverages because it can take up to two hours to feel the effects from the drug.[43] Additionally, marijuana purchased as a street drug may be laced with other substances like synthetic fentanyl that can cause overdose.

Benzodiazepine Overdose and Withdrawal

Rapid recognition and treatment of benzodiazepine withdrawal is critical because it can be life-threatening. Signs and symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal include tremors, anxiety, general malaise, perceptual disturbances, psychosis, seizures, and autonomic instability. Withdrawal is treated with a long-acting benzodiazepine (such as diazepam) and titrated to prevent withdrawal symptoms without causing excessive sedation or respiratory depression. The dose is then tapered gradually over a period of months.[44]

Sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytic intoxication cause behavioral or psychological changes similar to alcohol intoxication, such as inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior, mood lability, and impaired judgment. Symptoms of intoxication are as follows[45]:

- Slurred speech

- Incoordination

- Unsteady gait

- Nystagmus

- Impaired attention and memory

- Stupor or coma

Benzodiazepines are not detected by standard urine tests for drugs of abuse. However, specific benzodiazepine urine tests identify the metabolites of some benzodiazepines.[46]

Overdose

Benzodiazepines cause CNS depression and are commonly involved in drug overdose. They are often co-ingested with other drugs, such as alcohol or opioids that cause stupor, coma, and respiratory depression. When treating benzodiazepine overdose, end tidal CO2 (i.e., capnography) is used to monitor clients at risk for hypoventilation. Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required. Flumazenil is an antidote to reverse benzodiazepine-induced sedation following general anesthesia and procedural sedation. However, it is used cautiously for benzodiazepine overdose because it is associated with withdrawal seizures in individuals who have developed a tolerance to benzodiazepines. Supportive care is the mainstay of overdose management[47].

Hallucinogen Intoxication and Overdose

PCP intoxication causes problematic behavioral changes (e.g., belligerence, assaultiveness, impulsiveness, unpredictability, psychomotor agitation, impaired judgment) that occur during or shortly thereafter use.[48] Because of these symptoms, PCP is associated with violent and aggressive behavior including self-injury and violent criminal offenses (such as assaults, intimate partner violence, and homicide).[49] Within one hour of ingestion, two or more of the following signs or symptoms occur[50]:

- Vertical or horizontal nystagmus (an involuntary eye movement that causes the eye to rapidly move up and down or from side to side)

- Hypertension

- Tachycardia

- Numbness or diminished responsiveness to pain

- Ataxia (impaired balance or coordination)

- Slurred speech

- Muscle rigidity

- Seizures or coma

- Hyperacusis (sensitivity to noise)

Physical restraints may be necessary to control clients experiencing psychomotor agitation, followed by chemical sedation with intravenous benzodiazepines.

Overdose can occur with some dissociative drugs like phencyclidine (PCP). High doses of PCP can cause seizures, coma, and death, especially if taken with depressants such as alcohol or benzodiazepines.[51]

Stimulant Intoxication and Withdrawal

Stimulant intoxication causes problematic behavioral or psychological changes such as euphoria or blunted affect; changes in sociability; hypervigilance; interpersonal sensitivity; anxiety, tension, or anger; and impaired judgment. These are some symptoms of stimulant intoxication[52],:

- Tachycardia

- Hypertension

- Pupillary dilation

- Elevated or decreased blood pressure

- Perspiration or chills

- Nausea or vomiting

- Weight loss

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation

- Muscular weakness

- Respiratory depression

- Chest pain or cardiac dysrhythmias

- Confusion, seizures, or coma

- Psychosis/hallucinations

- Dyskinesia (involuntary, erratic, writhing movements of the face, arms, legs, or trunk)

- Dystonia (involuntary muscle contractions that result in slow repetitive movements)

It is important for nurses to be aware that individuals with acute stimulant intoxication may, without provocation, develop severe agitation with extreme violence and place themselves, family members, medical staff, and other clients at risk of major injury. Control of agitation and hyperthermia (body temperature over 41 degrees Celsius) receive top priority for treatment with the following interventions[53]:

- Intravenous benzodiazepines are administered immediately for chemical sedation of severely agitated individuals.

- Physical restraints should be avoided because clients who physically struggle against restraints undergo isometric muscle contractions that are associated with lactic acidosis, hyperthermia, sudden cardiac collapse, and death.

- Airway management with endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be required.

- Aggressive cooling is achieved through sedation, fluid resuscitation, external cooling blankets, or evaporative cooling techniques. Antipyretics are not used because the increased body temperature is caused by muscular activity, not an alteration in the hypothalamic temperature set point.

Inhalant Intoxication and Withdrawal

Inhalant intoxication causes problematic behavioral or psychological changes such as belligerence, assaultiveness, apathy, and impaired judgment. Inhalant intoxication includes these symptoms[54]:

- Dizziness

- Nystagmus

- Incoordination

- Slurred speech

- Unsteady gait

- Lethargy

- Depressed reflexes

- Psychomotor retardation

- Tremor

- Generalized muscle weakness

- Blurred or double vision

- Stupor or coma

- Euphoria

Long-term effects of inhalant use may include liver and kidney damage, hearing loss, bone marrow damage, loss of coordination and limb spasms (from nerve damage), delayed behavioral development (from brain problems), and brain damage (from cut-off oxygen flow to the brain).[55]

Acute intoxication with inhalants can cause life-threatening seizures and coma. Many solvents and aerosol sprays are highly concentrated with many other active ingredients; sniffing these products can cause the heart to stop within minutes. This condition, known as sudden sniffing death, can happen to otherwise healthy young people the first time they use an inhalant.[56].

Continued Treatment After Withdrawal

Withdrawal management is highly effective in preventing immediate and serious medical consequences associated with discontinuing substance use, but by itself, it is not an effective treatment for any substance use disorder. It is considered stabilization, meaning the patient is assisted through a period of acute detoxification and withdrawal to be medically stable and substance-free. Stabilization often prepares the individual for treatment. It is considered a first step toward recovery, similar to the acute management of a diabetic coma as a first step toward managing the underlying illness of diabetes. Similarly, acute stabilization and withdrawal management are most effective when followed by evidence-based treatments and recovery services.[57]

Unfortunately, many individuals who receive withdrawal management do not become engaged in long-term treatment. Studies have found that half to three-quarters of individuals with substance use disorders who receive withdrawal management services do not enter treatment. One of the most serious consequences when individuals do not begin continuing care after withdrawal management is overdose. Because withdrawal management reduces acquired tolerance, those who attempt to reuse their former substance in the same amount or frequency may overdose, especially those with opioid use disorders.[58]

- Sellers, E. M. (n.d.). CIWA-AR for alcohol withdrawal. MDCalc. https://www.mdcalc.com/ciwa-ar-alcohol-withdrawal#why-use ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, & National Institutes of Health. (2021, May). Understanding the dangers of alcohol overdose. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-dangers-of-alcohol-overdose ↵

- “NIAAA_BAC_Increases_Graphic.jpg” by The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-dangers-of-alcohol-overdose ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, & National Institutes of Health. (2021, May). Understanding the dangers of alcohol overdose. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-dangers-of-alcohol-overdose ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, & National Institutes of Health. (2021, May). Understanding the dangers of alcohol overdose. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-dangers-of-alcohol-overdose ↵

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, & National Institutes of Health. (2021, May). Understanding the dangers of alcohol overdose. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/understanding-dangers-of-alcohol-overdose ↵

- Lahood, A. J.& Kok, S.J. (2023, June 21). Ethanol toxicity. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557381/ ↵

- Lahood, A. J.& Kok, S.J. (2023, June 21). Ethanol toxicity. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557381/ ↵

- Pace, C. (2022). Alcohol withdrawal: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Pace, C. (2022). Alcohol withdrawal: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Pace, C. (2022). Alcohol withdrawal: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Pace, C. (2022). Alcohol withdrawal: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Pace, C. (2022). Alcohol withdrawal: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Pace, C. (2022). Alcohol withdrawal: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Hoffman, R. (2022). Management of moderate and severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms. UpToDate. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Vasan and Kumar and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (n.d). Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/wernicke-korsakoff-syndrome#:~:text=Korsakoff%20syndrome%20(also%20called%20Korsakoff's,the%20brain%20involved%20with%20memory. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Regina, A.C., Goyal, A. & Mechanic, O.J.(2025, January 22). Opioid toxicity. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470415/ ↵

- Eggleston, W., Podolak, C., Sullivan, R.W., Pacelli, L., Keenan, M., and Wojcik, S. (2018). A randomized usability assessment of simulated naloxone administration by community members. Addiction, 113(12):2300-2304. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14416 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). SAMHSA opioid overdose prevention toolkit: Five essential steps for first responders [Manual]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/five-essential-steps-for-first-responders.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). SAMHSA opioid overdose prevention toolkit: Five essential steps for first responders [Manual]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/five-essential-steps-for-first-responders.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). SAMHSA opioid overdose prevention toolkit: Five essential steps for first responders [Manual]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/five-essential-steps-for-first-responders.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). SAMHSA opioid overdose prevention toolkit: Five essential steps for first responders [Manual]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/five-essential-steps-for-first-responders.pdf ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). SAMHSA opioid overdose prevention toolkit: Five essential steps for first responders [Manual]. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/five-essential-steps-for-first-responders.pdf ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Wesson, D. R. (n.d.). COWS score for opiate withdrawal. MDCalc. https://www.mdcalc.com/cows-score-opiate-withdrawal#why-use ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2022, June 23). Methadone. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/medications-counseling-related-conditions/methadone ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Sevarino, K. A. (2022). Medically supervised opioid withdrawal during treatment for addiction. UpToDate. Retrieved March 19, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025, January 31). Cannabis frequently asked questions. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/cannabis/faq/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/marijuana/faqs.htm ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2022, March 2). Alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/atod ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Kang, M., Galuska, M.A., & Ghassemzadeh, S. (2023, June 26). Benzodiazepine toxicity. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482238/ ↵

- Kang, M., Galuska, M.A., & Ghassemzadeh, S. (2023, June 26). Benzodiazepine toxicity. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482238/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Crane, C. A., Easton, C. J., & Devine, S. (2013). The association between phencyclidine use and partner violence: An initial examination. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 32(2), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2013.797279. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2023, April). Psychedelic and dissociative drugs. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/psychedelic-dissociative-drugs ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Yasaei, R. & Saadabadi, A. (2023, May 1). Methamphetamine. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publications. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535356/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2024, September). Inhalants. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/inhalants ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2024, September). Inhalants. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/inhalants ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857 ↵

Interventions aimed at managing the physical and emotional symptoms that occur after a person suddenly stops using a psychoactive substance.

A rapid-onset, fluctuating disturbance of attention and cognition that is sometimes associated with hallucinations.