17.4 Applying the Nursing Process to Dementia Care

Terri J. Farmer, PhD, PMHNP, CNE

This section outlines the steps of the nursing process when providing care for adults with cognitive impairments.

Assessment — Recognizing Cues

Nurses provide care for older adults in a wide variety of settings including acute care facilities, clinics, adult day care facilities, retirement communities, long-term care facilities, private homes, and community-based residential facilities. It is vital for nurses to notice any signs of changing mental status based on the patient’s baseline. Any new or sudden changes that indicate possible delirium should be urgently reported to the health care provider for further assessment of potential underlying health conditions.

When assessing an adult patient with a previously diagnosed cognitive impairment, there are several assessments to include on admission. Their medical history should be reviewed and a medication reconciliation completed. A general survey provides a quick, overall assessment of the way an individual interacts with their environment and their overall mobility status. A comprehensive neurological assessment should be performed to establish a patient’s baseline neurological status. After a baseline status is determined, routine focused neurological assessments are performed to monitor for changes, such as asking the patient to state their name, place, and the date, as appropriate.

Additional assessments include functional status and the patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs). A decline in the ability to perform self-care and maintain ADLs can affect the individual’s well-being. Functional declines can bring about feelings of inadequacy and lead to depression. The ability to live independently relies on maintenance of self-care skills, including bathing, dressing, and toileting. Other factors that must be considered include the ability to adequately handle finances; maintain a clean, safe environment; and to shop and prepare meals. When deficits in these areas occur, resources should be recommended to assist the individual to meet these needs.

Cognitive changes, including disorientation, poor judgment, loss of language skills, and memory impairment, should be assessed objectively using standardized tools. Common standardized tools used to assess a patient’s mental status include the MMSE and the Mini-Cog.[1]

Cultural Considerations

Nurses provide culturally competent care for all individuals. Being aware of personal biases related to ageism and cognitive impairments is necessary when providing care for older adults experiencing confusion, memory deficits, and impaired judgment. Ageism is the stereotyping and discrimination against individuals or groups on the basis of their age. Ageism can take many forms, including prejudicial attitudes, discriminatory practices, or institutional policies and practices that perpetuate stereotypical beliefs. Ageism is widely prevalent and stems from the assumption that all members of a group (i.e., older adults) are the same and involves stereotyping and discrimination against individuals or groups on the basis of their age. Ageism has harmful effects on the health of older adults; research has shown that older adults with negative attitudes about aging may live 7.5 years less than those with positive attitudes. Some of this prejudice arises from observable biological declines and may be distorted by awareness of disorders such as dementia, which may be mistakenly thought to reflect normal aging. Socially ingrained ageism can become self-fulfilling by promoting stereotypes of social isolation, physical and cognitive decline, lack of physical activity, and economic burden in older adults.[2] These biases in health care personnel, patients, and family members can prevent early recognition and treatment of health problems like dementia, delirium, and depression.

Analyzing Cues and Prioritizing

Commonly used nursing concerns or diagnoses for older adults experiencing cognitive impairment include the following:

- Self-care deficit

- Risk for injury

- Impaired memory

- Impaired coping

- Social isolation

Risk for injury is a high priority for nurses. Mobility issues may increase fall risk and wandering behaviors may put the patient at risk for environmental injuries due to poor judgment. A common problem caused by dementia is Self-Care Deficit, defined as, “The inability to independently perform or complete cleansing activities; to put on or remove clothing; to eat; or to perform tasks associated with bowel and bladder elimination.” An associated condition with this nursing diagnosis is “alteration in cognitive functioning.”[3]

Outcome Identification, Generating Solutions, and Taking Action

An example of a broad, overall goal for an older adult experiencing cognitive impairment due to dementia is “The patient will perform self-care activities within the level of their own ability daily.”

An example of a SMART expected outcome criteria for a patient with cognitive impairment resulting in Self Care Deficit is “The patient will remain free of body odor during their hospital stay.”

There are many nursing interventions that can be implemented for older adults with impaired cognitive function based on their individual needs. Interventions focus on maintaining safety, meeting physical and psychological needs, and promoting quality of life. As always, refer to an evidence-based nursing care planning resource when customizing interventions for specific patients. See Table 17.2 for general nursing interventions to implement for clients with cognitive impairments.

Table 17.2 General Nursing Interventions for Cognitive Impairments

| Therapeutic Communication: Provide nursing care in a timely manner with an attitude of caring and compassion while maintaining the dignity of the individual. Establish a therapeutic relationship based on trust by sitting at the level of the patient and making in eye contact. |

| Reminiscence Therapy: Allow individuals opportunities to share their experiences and stories. This allows expression of personal identity and supports the individual’s coping and self-esteem. |

| Touch: When appropriate, touch provides comfort for individuals. It provides sensory stimulation to avoid sensory deprivation and demonstrates caring and warmth. It is important to assess the individual’s reaction to touch before implementing therapeutic gentle touch. |

| Reality Orientation: This technique provides awareness of person, place, time, and situation for those who are cognitively able. It restores a sense of reality, decreases confusion and disorientation, and promotes a healing environment. Older adults experiencing a change in environment or stressful situation benefit from the use of environmental cues for orientation, such as clocks, calendars, and whiteboards noting who is providing care and when they will return. |

| Validation Therapy: This technique is used for older adults who are confused. The focus is on the emotional aspect of their communication. This therapy avoids reorientation to time and place, even when incorrect, because this can trigger agitation in confused individuals. It does not reinforce incorrect perception but focuses on validating the patient’s feelings. |

Interventions for Symptomatic Behavior

Many people find the behavioral changes caused by AD to be the most challenging and distressing effect of the disease. The chief cause of behavioral symptoms is the progressive deterioration of brain cells. However, medication, environmental influences, and some medical conditions can also cause symptoms or make them worse.

In the early stages of AD, people may experience behavior and personality changes, such as irritability, anxiety, and depression. In later stages, other symptoms may occur, including the following:

- Aggression and anger

- Anxiety and agitation

- General emotional distress

- Physical or verbal outbursts

- Restlessness, pacing, or shredding paper or tissues

- Hallucinations (seeing, hearing, or feeling things that are not really there)

- Delusions (firmly held beliefs in things that are not true)

- Sleep issues and sundowning

Aggressive Behaviors

Aggressive behaviors may be verbal or physical. They can occur suddenly, with no apparent reason, or result from a frustrating situation. Although aggression can be hard to cope with, understanding this is a symptom of AD and the person with dementia is not acting this way on purpose can help. See Figure 17.4a[4] for an illustration of verbal aggression.

Aggression can be caused by many factors including physical discomfort, environmental factors, and poor communication. If the person with AD is aggressive, consider what might be contributing to the change in behavior.

Physical Discomfort

- Is the person able to let you know they are experiencing physical pain? It is not uncommon for persons with Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia to have chronic pain, urinary tract infections, or other conditions causing acute pain. Because of their loss of cognitive function, they are unable to articulate or identify the cause of physical discomfort and, therefore, may express it through physical aggression.

- Is the person tired because of inadequate rest or sleep?

- Is the person hungry or thirsty?

- Are medications causing side effects? Side effects are especially likely to occur when individuals are taking multiple medications for several health conditions.

Environmental Factors

- Is the person overstimulated by loud noises, an overactive environment, or physical clutter? Large crowds or being surrounded by unfamiliar people, even within one’s own home, can be overstimulating for a person with dementia.

- Does the person feel lost?

- What time of day is the person most alert? Most people function better during a certain time of day; typically, mornings are best. Consider the time of day when making appointments or scheduling activities. Choose a time when you know the person is most alert and best able to process new information or surroundings.

Poor Communication

- Are your instructions simple and easy to understand?

- Are you asking too many questions or making too many statements at once?

- Is the person picking up on your own stress or irritability?

Techniques for Response

There are many therapeutic methods for a nurse or caregiver to respond to aggressive behaviors displayed by a person with dementia. The following are some methods that can be used with aggressive behavior:

- Begin by trying to identify the immediate cause of the behavior. Think about what happened right before the reaction that may have triggered the behavior. Rule out pain as the cause of the behavior. Pain can trigger aggressive behavior for a person with dementia.

- Focus on the person’s feelings, not the facts. Look for the feelings behind the specific words or actions.

- Do not get upset. Be positive and reassuring and speak slowly in a soft tone.

- Limit distractions. Examine the person’s surroundings, and adapt them to avoid future triggers.

- Implement a relaxing activity. Try music, massage, or exercise to help soothe the person.

- Shift the focus to another activity. The immediate situation or activity may have unintentionally caused the aggressive response, so try a different approach.

- Take a break if needed. If the person is in a safe environment and you are able, walk away and take a moment for emotions to cool.

- Ensure safety! Make sure you and the person are safe. Be aware of the location of the person’s hands and feet in the event they become combative and try to strike out, kick, or bite you. If these interventions do not successfully calm down the person, seek assistance from others. If it is an emergency situation, call 911 and be sure to tell the responders the person has dementia that causes them to act aggressively.

When educating caregivers about responding to aggressive behaviors, encourage them to share their experience with others, such as face-to-face support groups, where they can share response strategies they have tried and also get more ideas from other caregivers.

Anxiety and Agitation

A person with Alzheimer’s may feel anxious or agitated. They may become restless, and feel a need to move around or pace or become upset in certain places or when focused on specific details. See Figure 17.4b[5] for an illustration of an older adult feeling the need to move around. Anxiety and agitation can be caused by several medical conditions, medication interactions, or by any circumstances that worsen the person’s ability to think. Ultimately, the person with dementia is biologically experiencing a profound loss of their ability to negotiate new information and stimuli. It is a direct result of the disease. Situations that may lead to agitation can include moving to a new residence or nursing home; changes in environment, such as travel, hospitalization, or the presence of houseguests; changes in caregiver arrangements; misperceived threats; or fear and fatigue resulting from trying to make sense out of a confusing world.

Interventions to prevent and treat agitation include the following:

- Create a calm environment and remove stressors. This may involve moving the person to a safer or quieter place or offering a security object, rest, or privacy. Providing soothing rituals and limiting caffeine use are also helpful.

- Avoid environmental triggers. Noise, glare, and background distraction (e.g. having the television on) can act as triggers.

- Monitor personal comfort. Check for pain, hunger, thirst, constipation, full bladder, fatigue, infections, and skin irritation. Make sure the room is at a comfortable temperature. Be sensitive to the person’s fears, misperceived threats, and frustration with expressing what is wanted.

- Simplify tasks and routines.

- Find outlets for the person’s energy. The person may be looking for something to do. Provide an opportunity for exercise such as going for a walk or putting on music and dancing.

Techniques for Response

If a patient with dementia becomes anxious or agitated, consider these potential interventions:

- Back off and ask permission before performing care tasks. Use calm, positive statements, slow down, add lighting, and provide reassurance. Offer guided choices between two options when possible. Focus on pleasant events and try to limit stimulation.

- Use effective language. When speaking, try phrases such as, “May I help you?” “You’re safe here.” “Everything is under control.” “I’m sorry you are upset.” “I know it’s hard.” “I will stay with you until you feel better.”

- Listen to the person’s frustration. Find out what may be causing the agitation and try to understand.

- Check yourself. Do not raise your voice; show alarm or offense; or corner, crowd, restrain, criticize, ignore, or argue with the person. Take care not to make sudden movements out of the person’s view. Be aware of the patient’s hands and feet in the event they strike out or kick at you.

If the person’s anxiety or agitation does not improve using these techniques, notify the provider to rule out physiological causes or medication-related side effects.

Hallucinations

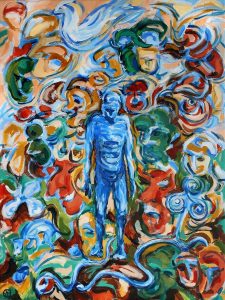

When a person with dementia experiences hallucinations, they may see, hear, smell, taste, or feel something that is not’t there. Some hallucinations may be frightening, whereas others may involve ordinary visions of people, situations, or objects from the past. AD and other dementias are not the only cause of hallucinations. Other causes of hallucinations include schizophrenia; physical problems, such as kidney or bladder infections, dehydration, or intense pain; alcohol or drug abuse; eyesight or hearing problems; and medications. See Figure 17.4c[13] for an illustration of hallucinations experienced by a person with dementia.

If a person with dementia begins hallucinating, notify the health care provider to rule out other possible causes and to determine if medication is needed. It may also help to have the person’s eyesight or hearing checked. If these strategies fail and symptoms are severe, medication may be prescribed. Although antipsychotic medications can be effective in some situations, they are associated with an increased risk of stroke and death in older adults with dementia and must be used carefully.

Techniques for Response

When responding to a patient with dementia experiencing hallucinations, be cautious. First, assess the situation and determine whether the hallucination is a problem for the person or for you. Is the hallucination upsetting? Is it leading the person to do something dangerous? Is the sight of an unfamiliar face causing the person to become frightened? If so, react calmly and quickly with reassuring words and a comforting touch. Do not argue with the person about what they see or hear. If the behavior is not dangerous, there may not be a need to intervene.

- Offer reassurance. Respond in a calm, supportive manner. You may want to respond with, “Don’t worry. I’m here. I’ll protect you. I’ll take care of you.” Gentle patting may turn the person’s attention toward you and reduce the hallucination.

- Acknowledge the feelings behind the hallucination and try to find out what the hallucination means to the individual. You might want to say, “It sounds as if you’re worried” or “This must be frightening for you.”

- Use distractions. Suggest a walk or move to another room. Frightening hallucinations often subside in well-lit areas where other people are present. Try to turn the person’s attention to music, conversation, or activities they enjoy.

- Respond honestly. If the person asks you about a hallucination or delusion, be honest. For example, if they ask, “Do you see the spider on the wall?,” you can respond, “I know you see something, but I don’t see it.” This way you’re not denying what the person sees or hears and avoiding escalating their agitation.

- Modify the environment. Check for sounds that might be misinterpreted, such as noise from a television or an air conditioner. Look for lighting that casts shadows, reflections, or distortions on the surfaces of floors, walls, and furniture. Turn on lights to reduce shadows. Cover mirrors with a cloth or remove them if the person thinks that he or she is looking at a stranger.

Sundowning

Sundowning is increased confusion, anxiety, agitation, pacing, and disorientation in patients with dementia that typically begins at dusk and continues throughout the night. Although the exact cause of sundowning and sleep disorders in people with AD is unknown, these changes result from the disease’s impact on the brain. There are several factors that may contribute to sleep disturbances and sundowning:

- Mental and physical exhaustion from a full day trying to keep up with an unfamiliar or confusing environment

- An upset in the “internal body clock,” causing a biological mix-up between day and night

- Reduced lighting causing shadows and misinterpretation is seen, causing agitation

- Nonverbal behaviors of others, especially if stress or frustration is present

- Disorientation due to the inability to separate dreams from reality when sleeping

- Decreased need for sleep, a common condition among older adults

There are several interventions that nurses and caregivers can implement to help manage sleep issues and sundowning:

- Promote plenty of rest.

- Encourage a regular routine of waking up, eating meals, and going to bed.

- When possible and appropriate, include walks or time outside in the sunlight.

- Make notes about what happens before sundowning events and try to identify triggers.

- Reduce stimulation during the evening hours (e.g., TV, doing chores, loud music). These distractions may add to the person’s confusion.

- Offer a larger meal at lunch and keep the evening meal lighter.

- Keep the home environment well lit in the evening. Adequate lighting may reduce the person’s confusion.

- Do not physically restrain the person; it can make agitation worse.

- Try to identify activities that are soothing to the person, such as listening to calming music, looking at photographs, or watching a favorite movie.

- Take a walk with the person to help reduce their restlessness.

- Consider the best times of day for administering medication; consult with the prescribing provider or pharmacist as needed.

- Limit daytime naps if the person has trouble sleeping at night.

- Reduce or avoid alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine that can affect the ability to sleep.

- Discuss the situation with the provider when behavioral interventions and environmental changes do not work. Additional medications may be prescribed.

Caregiver Role Strain

Eighty-three percent of the help provided to people living with dementia in their homes in the United States comes from family members, friends, or other unpaid caregivers. Approximately one-fourth of dementia caregivers are also “sandwich generation” caregivers meaning that they care not only for an aging parent, but also for children younger than 18 years.

Dementia can take a devastating toll on caregivers. Compared with caregivers of people without dementia, twice as many caregivers of people with dementia indicate substantial emotional, financial, and physical difficulties.[6] See Figure 17.4d[7] for an image of a caregiver daughter caring for her mother with dementia.

The caregivers of patients with dementia frequently report experiencing high levels of stress that often eventually affect their health and well-being. Nurses should monitor caregivers for these symptoms of stress:

- Denial about the disease and its effect on the person who has been diagnosed. For example, the caregiver might say, “I know Mom is going to get better.”

- Anger at the person with AD or frustration that they cannot do the things they used to be able to do. For example, the caregiver might say, “He knows how to get dressed, he’s just being stubborn.”

- Social withdrawal from friends and activities. For example, the caregiver may say, “I don’t care about visiting with my friends anymore.”

- Anxiety about the future and facing another day. For example, the caregiver might say, “What happens when he needs more care than I can provide?”

- Depression or decreased ability to cope. For example, the caregiver might say, “I just don’t care anymore.”

- Exhaustion that makes it difficult to complete necessary daily tasks. For example, the caregiver might say, “I’m too tired to prepare meals.”

- Sleeplessness caused by concerns. For example, the caregiver might say, “What if she wanders out of the house or falls and hurts herself?”

- Irritability, moodiness, or negative responses.

- Lack of concentration that makes it difficult to perform familiar tasks. For example, the caregiver might say, “I was so busy, I forgot my appointment.”

- Health problems that begin to take a mental and physical toll. For example, the caregiver might say, “I can’t remember the last time I felt good.”

Nurses should monitor for these signs of caregiver stress and provide information about community resources. (See additional information about community resources below.) Caregivers should be encouraged to take good care of themselves by visiting their health care provider, eating well, exercising, and getting plenty of rest. It is helpful to remind caregivers that “taking care of yourself and being healthy can help you be a better caregiver.” Teach them relaxation techniques, such as relaxation breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, visualization, and meditation.

Caregivers should also be educated about additional care options, such as adult day care, respite care, residential facilities, or hospice care. Adult day care centers offer people with dementia and other chronic illnesses the opportunity to be social and to participate in activities in a safe environment, while also giving their caregivers the opportunity to work, run errands, or take a break. Respite care can be provided at home (by a volunteer or paid service) or in a care setting, such as adult day care or residential facility, to provide the caregiver a much-needed break. If the person with Alzheimer’s or other dementia prefers a communal living environment or requires more care than can be safely provided at home, a residential facility may be the best option for providing care. Different types of facilities provide different levels of care, depending on the person’s needs. Hospice care is a type of care selected by patients who are terminally ill and whose health care provider has determined they are expected to live six months or less. It focuses on providing comfort and dignity at the end of life with supportive services that can be of great benefit to people in the final stages of dementia and their families.

Read about alternative care options and caregiver support at the Alzheimer Association web page.

Community Resources

Local Alzheimer’s Association chapters can connect families and caregivers with the resources they need to cope with the challenges of caring for individuals with AD.

- Find an Alzheimer’s Association chapter in your community by visiting the Get Involved with Your Local Chapter web page.

- The Alzheimer’s Association 24/7 Helpline (800.272.3900) is available around the clock, 365 days a year. Through this free service, specialists and master’s-level clinicians offer confidential support and information to people living with dementia, caregivers, families, and the public.

The Alzheimer’s Association has a free virtual library web page devoted to resources that increase knowledge about Alzheimer’s and other dementias.[8]

Evaluation

It is important to routinely evaluate the effectiveness of customized interventions for patients with cognitive impairments. Review the SMART outcomes established for each specific patient to determine if interventions are effectively promoting safety while also maintaining physiological and psychological needs and promoting quality of life. Modify the care plan when needed to meet these outcome criteria.

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- World Health Organization. (2024). Ageism. https://www.who.int/health-topics/ageism ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification 2021-2023, Twelfth Edition. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- “5012292106_507e008c7a_o.jpg” by borosjuli is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- “old-63622_960_720.jpg” by geralt is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

- “My_mum_ill_with_dementia_with_me.png” by MariaMagdalens is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2025). What is Alzheimer's? Alzheimer’s Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers ↵

Prejudice or discrimination against people based on their age. Ageism has a negative impact on physical and menatl health.

A period of increased confusion, anxiety, agitation, pacing, and disorientation in patients with dementia that often begins at dusk and continues throughout the night. The cause is unknown.

Care that offers people with dementia and other chronic illnesses the opportunity to be social and to participate in activities in a safe environment, while also giving their caregivers the opportunity to work, run errands, or take a much-needed break.

Care provided at home (by a volunteer or paid service) or in a care setting, such as adult day care or residential facility, that allows the caregiver to take a much-needed break.

Patient- and family-centered care that begins after treatment of disease is stopped because the condition is not survivable. The focus is on symptom management and quality of life.