2.2 The Roles of Stress and Coping

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Stress is a common experience for patients and healthcare personnel alike. Everyone experiences stress during their lives. High levels of stress can cause symptoms like headaches, back pain, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Chronic stress contributes to the development of chronic illnesses, including acute physical illnesses due to decreased effectiveness of the immune system and disorders of mental health. It is important for nurses to recognize signs and symptoms of stress in themselves and others, as well as encourage effective stress management strategies. An optimal healing environment for patients includes stress management for all. This section begins with a review of the stress response and signs and symptoms of stress. A discussion of stress management techniques that nurses may use or encourage their patients to try is included.

Stress Response

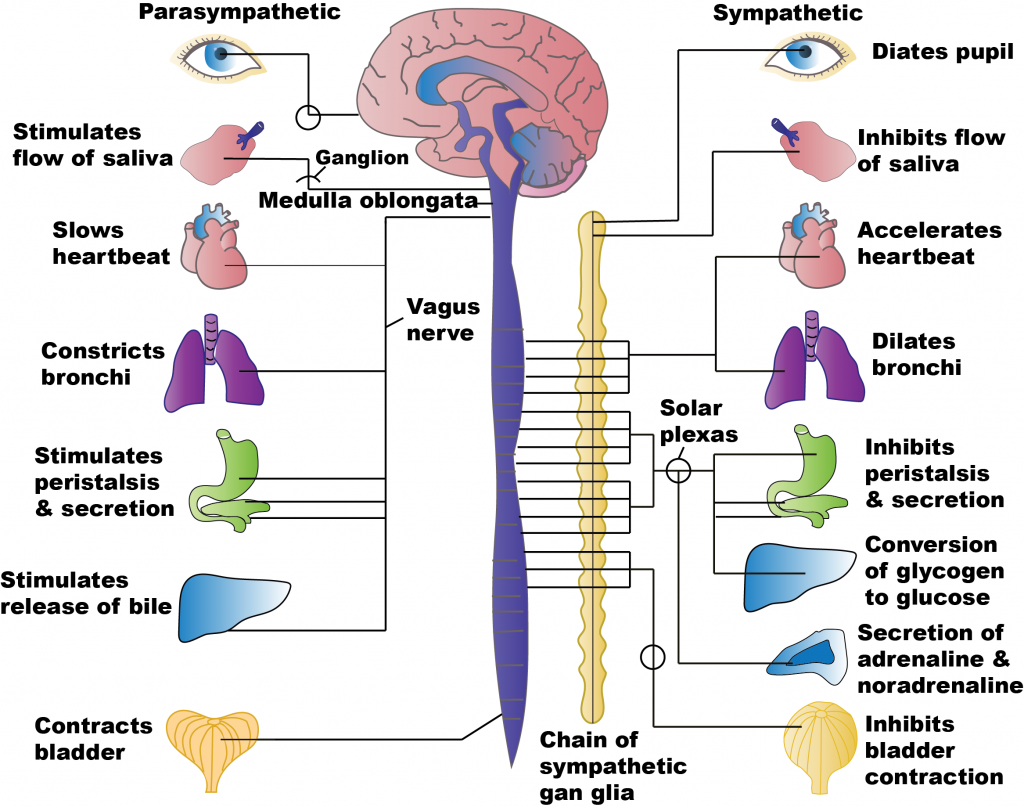

Stressors are any internal or external event, force, or condition that results in physical or emotional stress.[1] The body’s sympathetic nervous system (SNS) responds to actual or perceived stressors with the “fight, flight, or freeze” (faint is sometimes included) stress response. Several reactions occur during the stress response that help the individual to achieve the purpose of either fighting or running. The respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems are activated to breathe rapidly, stimulate the heart to pump more blood, dilate the blood vessels, and increase blood pressure to deliver more oxygenated blood to the muscles. The liver creates more glucose for energy for the muscles to use to fight or run. Pupils dilate to see the threat (or the escape route) more clearly. Sweating prevents the body from overheating from excess muscle contraction. Because the digestive system is not needed during this time of threat, the body shunts oxygen-rich blood to the skeletal muscles. To coordinate all these targeted responses, hormones, including epinephrine, norepinephrine, and glucocorticoids (including cortisol, often referred to as the “stress hormone”), are released by the endocrine system via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) and dispersed to the many SNS neuroreceptors on target organs simultaneously.[2] After the response to the stressful stimuli has resolved, the body returns to the pre-emergency state facilitated by the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) that has opposing effects to the SNS. See Figure 2.2a[3] for an image comparing the effects of stimulating the SNS and PNS.

Responding to acute stress is a normal function of the body. These processes keep people safe and allow them to learn and problem solve. For example, the stress response allows nurses to function logically during care of a patient in cardiac arrest.

Effects of Chronic Stress

The “fight or flight or freeze” stress response equips our bodies to quickly respond to life-threatening stressors. However, exposure to long-term stress can cause serious effects on the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and reproductive systems.[4] Consistent and ongoing increases in heart rate and blood pressure and elevated levels of stress hormones contribute to inflammation in arteries and can increase the risk for hypertension, heart attack, or stroke.[5]

During sudden onset stress, muscles contract and then relax when the stress passes. However, during chronic stress, muscles in the body are often in a constant state of vigilance that may trigger other reactions of the body and even promote stress-related disorders. For example, tension-type headaches and migraine headaches are associated with chronic muscle tension in the area of the shoulders, neck, and head. Musculoskeletal pain in the lower back and upper extremities has also been linked to job stress.[6]

During an acute stressful event, an increase in cortisol can provide the energy required to deal with prolonged or extreme challenges. However, chronic stress can result in an impaired immune system that has been linked to the development of numerous physical and mental health conditions, including chronic fatigue, metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes, obesity), depression, and immune disorders.[7]

When chronically stressed, individuals may eat much more or much less than usual. Increased food, alcohol, or tobacco can result in acid reflux. Stress can induce muscle spasms in the bowel and can affect how quickly food moves through the gastrointestinal system, causing either diarrhea or constipation. Stress especially affects people with chronic bowel disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease or irritable bowel syndrome. This may be due to the nerves in the gut being more sensitive, changes in gut microbiota, changes in how quickly food moves through the gut, and/or changes in gut immune responses.[8]

Excess amounts of cortisol can affect the normal biochemical functioning of the male reproductive system. Chronic stress can affect testosterone production, resulting in a decline in sex drive or libido, erectile dysfunction, or impotence. It can negatively impact sperm production and maturation, causing difficulties in couples who are trying to conceive. Researchers have found that men who experienced two or more stressful life events in the past year had a lower percentage of sperm motility and a lower percentage of sperm of normal morphology (size and shape) compared with men who did not experience any stressful life events.[9]

In the female reproductive system, stress affects menstruation and may be associated with absent or irregular menstrual cycles, more painful periods, and changes in the length of cycles. It may make premenstrual symptoms worse or more difficult to cope with, such as cramping, fluid retention, bloating, negative mood, and mood swings. Chronic stress may also reduce sexual desire. Stress can negatively impact a woman’s ability to conceive, the health of her pregnancy, and her postpartum adjustment. Maternal stress can negatively impact fetal development, disrupt bonding with the baby following delivery, and increase the risk of postpartum depression.[10]

Relaxation techniques and other stress-relieving activities have been shown to effectively reduce muscle tension, decrease the incidence of stress-related disorders, and increase a sense of well-being. For individuals with chronic pain conditions, stress-relieving activities have been shown to improve mood and daily function.[11]

Adverse Childhood Experiences and Chronic Stress

Adults with adverse childhood experiences or exposure to adverse life events often experience ongoing chronic stress with an array of physical, mental, and social health problems throughout adulthood. Some of the most common health risks include physical and mental illness, substance use disorder, and a high level of engagement in risky sexual behavior.[12]

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, parental loss, or parental separation before the child is 18 years old. Individuals who have experienced four or more ACEs are at a significantly higher risk of developing mental, physical, and social problems in adulthood. Research has established that early life stress is a predictor of smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug dependence. Adults who experienced ACEs related to maladaptive family functioning (parental mental illness, substance use disorder, criminality, family violence, physical and sexual abuse, and neglect) are at higher risk for developing mood, substance abuse, and anxiety disorders. ACEs are also associated with an increased risk of the development of malignancy, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and other chronic debilitating conditions.[13] ACES are discussed in detail in Chapter 15.2.

Signs and Symptoms of Stress

Nurses are often the first to notice signs and symptoms of stress and can help make their patients aware of these symptoms. Common signs and symptoms of chronic stress are as follows[14],[15]:

- Irritability

- Fatigue

- Headaches

- Difficulty concentrating

- Rapid, disorganized thoughts

- Difficulty sleeping

- Digestive problems

- Changes in appetite

- Feeling helpless

- A perceived loss of control

- Low self-esteem

- Loss of sexual desire

- Nervousness

- Frequent infections or illnesses

- Vocalized suicidal thoughts

When providing patients with stress management techniques and effective coping strategies, nurses must be aware of common defense mechanisms. Defense mechanisms are reaction patterns used by individuals to protect themselves from anxiety that arises from stress and conflict and allow them to maintain a self-image and continue functioning.[16] Defense mechanisms may not always be apparent to the individual engaging in them. With the exception of suppression, all other defense mechanisms may not be under conscious control so the individual may not be aware of using them. We all use defense mechanisms, generally in healthy ways. However, excessive use of defense mechanisms is associated with mental health disorders. See Table 2.2 for a description of common defense mechanisms.

Table 2.2 Common Defense Mechanisms

| Defense Mechanisms | Definitions | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conversion

(always pathological) |

Anxiety caused by repressed impulses and feelings are converted into a physical symptoms.[17] | An individual scheduled to see their therapist to discuss a past sexual assault experiences a severe headache and cancels the appointment. |

| Denial | Unpleasant thoughts, feelings, wishes, or events are ignored or excluded from conscious awareness to protect themselves from overwhelming worry or anxiety.[18],[19] | A patient recently diagnosed with cancer states there was an error in diagnosis and they don’t have cancer.

Other examples include denial of a financial problem, an addiction, or a partner’s infidelity. |

| Dissociation | A feeling of being disconnected from a stressful or traumatic event – or feeling that the event is not really happening – to block out mental trauma and protect the mind from too much stress.[20] | A person imagines being in a serene place while physically being in a noisy, chaotic environment.

A person experiencing physical abuse may feel as if they are floating above their bodies observing the situation. |

| Displacement | Unconscious transfer of one’s emotions or reaction from an original object to a less-threatening target to discharge tension.[21] | An individual who is angry with their partner kicks the family dog. An angry child breaks a toy or yells at a sibling instead of attacking their father. A frustrated employee criticizes their spouse instead of their boss.[22] |

| Introjection | Unconsciously incorporating the attitudes, values, and qualities of another person’s personality.[23] | A person talks and acts like someone they admire. |

| Projection

(always pathological) |

A process when one attributes their individual positive or negative characteristics, affects, and impulses to another person or group.[24] | A person conflicted over expressing anger changes “I hate him” to “He hates me.”[25] |

| Rationalization | Logical reasons are given to justify unacceptable behavior to defend against feelings of guilt, maintain self-respect, and protect oneself from criticism.[26] | A person who is overextended on several credit cards rationalizes it is okay to buy more clothes to be in style when spending money that was set aside to pay for the monthly rent and utilities. A student caught cheating on a test rationalizes, “Everybody cheats.” |

| Reaction Formation | Unacceptable or threatening impulses are denied and consciously replaced with an opposite, acceptable impulse.[27] | A patient who hates their mother writes in their journal that their mom is a wonderful mother. |

| Regression | A return to a prior, lower state of cognitive, emotional, or behavioral functioning when threatened with overwhelming external problems or internal conflicts.[28] | A child who was toilet trained reverts to wetting their pants after their parents’ divorce. |

| Repression | Painful experiences and unacceptable impulses are unconsciously excluded from consciousness as a protection against anxiety.[29] | A victim of incest indicates they have always hated their brother (the molester) but cannot remember why. |

| Splitting | Objects provoking anxiety and ambivalence are viewed as either all good or all bad.[30] | A patient tells the nurse they are the most wonderful person in the world, but after the nurse enforces the unit rules with them, the patient tells the nurse they are the worst person they have ever met. |

| Suppression | A conscious effort to keep disturbing thoughts and experiences out of mind or to control and inhibit the expression of unacceptable impulses and feelings. Suppression is similar to repression, but it is a conscious process.[31],[32] | An individual has an impulse to tell their boss what they think about them and their unacceptable behavior, but the impulse is suppressed because of the need to keep the job. |

| Sublimation | Unacceptable sexual or aggressive drives are unconsciously channeled into socially acceptable modes of expression that indirectly provide some satisfaction for the original drives and protect individuals from anxiety induced by the original drive.[33] | An individual with an exhibitionistic impulse channels this impulse into creating dance choreography. A person with a voyeuristic urge completes scientific research and observes research subjects. An individual with an aggressive drive joins the football team.[34] |

Stress Management

Techniques for the management of stress are useful for both nurses and their patients. Recognizing signs and symptoms of stress allows individuals to implement stress management strategies. Nurses can educate patients about effective strategies for reducing the stress response. Effective strategies include the following[35],[36]:

- Set personal and professional boundaries.

- Maintain a healthy social support network.

- Select healthy food choices.

- Engage in regular physical exercise.

- Get an adequate amount of sleep each night.

- Set realistic and fair expectations.

Setting limits is essential for effectively managing stress. Individuals should list activities and relationships that lead to feeling overwhelmed, identify essential tasks, and cut back on nonessential tasks. For work-related or school-related responsibilities a discussion with supervisors or school officials can help limit expectations while the individual learns stress management. Encourage individuals to refrain from accepting any more commitments until they feel their stress is under control.[37]

Maintaining a healthy social support network with supportive people, such as friends or family, can provide emotional support.[38] Caring relationships and healthy social connections lead to better resilience.

Physical activity increases the body’s production of endorphins that boost the mood and reduce stress. Nurses can educate patients that a walk or other aerobic activity can increase energy and concentration levels and lessen feelings of anxiety.[39]

People who are chronically stressed often suffer from lack of adequate sleep and, in some cases, stress-induced insomnia. Nurses can educate individuals how to take steps to increase the quality of sleep. Experts recommend a regular pattern of sleep and wake times, striving for at least 6-8 hours of sleep, and, if possible, eliminating distractions, such as television, cell phones, and computers from the bedroom. Begin winding down an hour or two before bedtime and engage in calming activities such as listening to relaxing music, reading an enjoyable book, taking a soothing bath, or practicing relaxation techniques like meditation. Avoid eating a heavy meal or engaging in intense exercise immediately before bedtime. If a person tends to lie in bed worrying, encourage them to write down their concerns and plan to address them in the morning.[40]

Nurses can encourage patients to set realistic expectations, examine problems for potential opportunities, and refute thinking errors to minimize stress. Setting realistic expectations and reframing the way one looks at stressful situations can make stressors seem more manageable. Patients should be encouraged to keep challenges in perspective and break them into smaller reasonable tasks.[41]

Nurses can educate patients that powerful thoughts and feelings are a natural part of stress, but problems can occur if we get “hooked” by them. For example, one minute you might be enjoying a meal with family, and the next moment you get “hooked” by angry thoughts and feelings. Stress can make someone feel as if they are being pulled away from the values of the person they want to be, such as being calm, caring, attentive, committed, persistent, and courageous.[42]

There are many kinds of difficult thoughts and feelings that can “hook us,” such as, “This is too hard,” “I give up,” “I am never going to get this,” “They shouldn’t have done that,” or memories about difficult events that have occurred in our lives. When we get “hooked,” our behavior changes. We may do things that make our lives worse, like getting into more disagreements, withdrawing from others, or spending too much time lying in bed. These are called “away moves” because they move us away from our values. Sometimes emotions become so strong they feel like emotional storms. However, there are steps we can take”[43]

WHO Stress Management Guide

The World Health Organization (WHO) shares techniques for working with difficult thoughts and feelings in a guide titled Doing What Matters in Times of Stress. This guide discusses five categories of techniques and skills that, based on evidence and field testing, can reduce overall stress levels even if only used for a few minutes each day. These categories include 1. Grounding, 2. Unhooking, 3. Acting on our values, 4. Being kind, and 5. Making room.[44]

Grounding

“Grounding” is a helpful tool when feeling distracted or having trouble focusing on a task and/or the present moment. The first step of grounding is to notice how you are feeling and what you are thinking. Next, slow down and connect with your body by focusing on your breathing. Exhale completely and wait three seconds, and then inhale as slowly as possible. Slowly stretch your arms and legs and push your feet against the floor. The next step is to focus on the world around you. Notice where you are and what you are doing. Use your five senses. What are five things you can see? What are four things you can hear? What can you smell? Tap your leg or squeeze your thumb and count to ten. Touch your knees or another object within reach. What does it feel like? Grounding counteracts the effects of the sympathetic nervous system through removing us from the ‘hook’ of negative thoughts and bringing us into the present moment where the thoughts are not relevant.[45]

Unhooking

At times we may have unwanted, intrusive, negative thoughts that negatively affect us. “Unhooking” is a tool to manage and decrease the impact of these unwanted thoughts. First, notice that a thought or feeling has hooked you, and then name it. Naming it begins by silently saying, “Here is a thought,” or “Here is a feeling.” By adding “I notice,” it unhooks us even more. For example, “I notice there is a knot in my stomach.” The next step is to refocus on what you are doing, fully engage in that activity, and pay full attention to whoever is with you and whatever you are doing. For example, if you are having dinner with family and notice feelings of anger, note “I am having feelings of anger,” but choose to refocus and engage with family.[46]

Acting on Our Values

The third category of skills is called “Acting on Our Values.” This means, despite challenges and struggles we are experiencing, we will act in line with what is important to us and our beliefs. Even when facing difficult situations, we can still make the conscious choice to act in line with our values. The more we focus on our own actions, the more we can influence our immediate world and the people and situations we encounter every day. We must continually ask ourselves, “Are my actions moving me toward or away from my values?” Remember that even the smallest actions have impact, just as a giant tree grows from a small seed. Even in the most stressful of times, we can take small actions to live by our values and maintain or create a more satisfying and fulfilling life. These values may include self-compassion and care. By caring for oneself, we ultimately have more energy and motivation to then help others.[47]

For information on self-compassion and self-care, see: Self-Compassion Practices: Cultivate Inner Peace and Joy – Self-Compassion.

Being Kind

“Being Kind” is a fourth tool for reducing stress. Kindness can make a significant difference to our mental health by being kind to others, as well as to ourselves. A simple thank you or a small act can provide a boost in well-being.

Making Room

“Making Room” is a fifth tool for reducing stress. Sometimes trying to push away painful thoughts and feelings does not work very well. In these situations, it is helpful to notice and name the feeling, and then “make room” for it. “Making room” means allowing the painful feeling or thought to come and go like the weather. Nurses can educate patients that as they breathe, they should imagine their breath flowing into and around their pain and making room for it. Instead of fighting with the thought or feeling, they should allow it to move through them, just like the weather moves through the sky. If patients are not fighting with the painful thought or feeling, they will have more time and energy to engage with the world around them and do things that are important to them.[48]

Read Doing What Matters in Times of Stress by the World Health Organization (WHO) for more information.

View the following YouTube video on the WHO Stress Management Guide[49]:

Stress Related to World Events

The COVID-19 pandemic had a major effect on many people’s lives. Many health care professionals faced challenges that were stressful, overwhelming, and caused strong emotions. Additionally, world events such as political unrest, war, suffering, and injustice profoundly affect patients and healthcare professionals. Learning to cope with stress in a healthy way can increase feelings of resiliency. Here are ways to help manage stress resulting from world events[50]:

- Take breaks from watching, reading, or listening to news stories and social media. Being informed is important but consider limiting news to just a couple times a day and disconnecting from phones, TVs, and computer screens for a while.

- It can be important to do a self check-in before reading any news. “Do I have the emotional energy to handle a difficult headline if I see one?”

- Take care of your body.

- Take deep breaths, stretch, or meditate

- Try to eat healthy, well-balanced meals

- Exercise regularly

- Get plenty of sleep

- Avoid excessive alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and substance use

- Continue routine preventive measures (such as vaccinations, cancer screenings, etc.) as recommended by your health care provider

- Make time to unwind. Plan activities you enjoy.

- Purposefully connect with others. It is especially important to stay connected with your friends and family. Helping others cope through phone calls or video chats can help you and your loved ones feel less lonely or isolated. Connect with your community organizations.

- Use the techniques described in the WHO stress management guide.[51]

More Strategies for Self-Care

By becoming self-aware regarding signs of stress, you can implement self-care strategies to prevent compassion fatigue and burnout. Use the following “A’s” to assist in building resilience, connection, and compassion[52]:

- Attention: Become aware of your physical, psychological, social, and spiritual health. What are you grateful for? What are your areas of improvement? This protects you from drifting through life on autopilot.

- Acknowledgement: Honestly look at all you have witnessed as a health care professional. What insight have you experienced? Acknowledging the pain of loss you have witnessed protects you from invalidating the experiences.

- Affection: Choose to look at yourself with kindness and warmth. Affection and self-compassion prevent you from becoming bitter and “being too hard” on yourself.

- Acceptance: Choose to be at peace and welcome all aspects of yourself. By accepting both your talents and imperfections, you can protect yourself from impatience, victim mentality, and blame.

The health consequences of chronic stress depend on an individual’s coping styles and their resilience to real or perceived stress. Coping refers to cognitive and behavioral efforts made to master, tolerate, or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts.[53]

Coping strategies are actions, a series of actions, or thought processes used in meeting a stressful or unpleasant situation or in modifying one’s reaction to such a situation. Coping strategies are classified as adaptive or maladaptive. Adaptive coping strategies include problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping typically focuses on seeking treatment such as counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy. Emotion-focused coping includes strategies such as mindfulness, meditation, and yoga; using humor and jokes; seeking spiritual or religious pursuits; engaging in physical activity or breathing exercises; and seeking social support.

Maladaptive coping responses include avoidance of the stressful condition, withdrawal from a stressful environment, disengagement from stressful relationships, and misuse of drugs and/or alcohol.[54] Nurses can educate individuals and their family members about adaptive, emotion-focused coping strategies and make referrals to healthcare team members for problem-focused coping and treatment options for individuals experiencing maladaptive coping responses to stress.

Emotion-Focused Coping Strategies

Nurses can educate patients about many emotion-focused coping strategies, such as meditating, practicing yoga, journaling, praying, spending time in nature, nurturing supportive relationships, and practicing mindfulness.

Meditation

Mindfulness is a form of meditation that uses breathing and thought techniques to create an awareness of one’s body and surroundings. Research suggests that mindfulness can have a positive impact on stress, anxiety, and depression.[55] Meditation can induce feelings of calm and clear-headedness and improve concentration and attention. Research has shown that meditation increases the brain’s gray matter density, which can reduce sensitivity to pain, enhance the immune system, help regulate difficult emotions, and relieve stress. Meditation has been proven helpful for people with depression and anxiety, cancer, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, rheumatoid arthritis, type 2 diabetes, chronic fatigue syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.[56] There are many ways to learn about meditation including books, classes, and online applications. No special setting or equipment is necessary. Meditation may not be beneficial for patients with certain psychiatric conditions so the healthcare team should be involved in decisions about proper use. See Figure 2.2b[57] for an image of an individual participating in meditation.

Yoga

Yoga is a centuries-old spiritual practice that creates a sense of union within the practitioner through physical postures, ethical behaviors, and breath expansion. The systematic practice of yoga has been found to reduce inflammation and stress, decrease depression and anxiety, lower blood pressure, and increase feelings of well-being.[58] Simple yoga stretches and positions are helpful and can be taught to many patients. A certified yoga instructor is needed when full program of yoga is involved. See Figure 2.2c[59] for an image of an individual participating in yoga.

Journaling

Journaling can help a person become more aware of their inner life and feel more connected to experiences. Studies show that writing during difficult times may help a person find meaning in life’s challenges and become more resilient in the face of obstacles. When journaling, it can be helpful to focus on three basic questions: What experiences give me energy? What experiences drain my energy? Were there any experiences today where I felt alive and experienced “flow”? Allow yourself to write freely, without stopping to edit or worry about spelling and grammar.[60]

Spiritual Practices

Spirituality is defined as a dynamic and intrinsic aspect of humanity through which persons seek ultimate meaning, purpose, and transcendence and experience relationship to self, family, others, community, society, nature, and the significant or sacred.[61] Spiritual needs and spirituality are often mistakenly equated with religion, but spirituality is a broader concept. Other elements of spirituality include meaning, love, belonging, forgiveness, and connectedness.[62]Spiritual practices can elicit the relaxation response, along with feelings of hope, gratitude, and compassion, all of which have a positive effect on overall well-being. [63] Individuals can be encouraged to find a spiritual community, a local group that meets to discuss spiritual issues. The benefits of social support are well-documented, and having a spiritual community to turn to for fellowship can provide a sense of belonging and support.[64] Spending time in nature is cited by many individuals as a spiritual practice that contributes to their mental health.[65]

Supportive Relationships

Individuals should be encouraged to nurture supportive relationships with family, significant others, and friends. Relationships aren’t static – they are living, dynamic aspects of our lives that require attention and care. To benefit from strong connections with others, individuals should take charge of their relationships and devote time and energy to support them. It can be helpful to create rituals together. With busy schedules and the presence of online social media that offer the façade of real contact, it’s very easy to drift from friends. Research has found that people who deliberately make time for gatherings enjoy stronger relationships and more positive energy. An easy way to do this is to create a standing ritual that you can share and that doesn’t create more stress, such as talking on the telephone on Fridays or sharing a walk during lunch breaks.[66]

Mindfulness

Mindfulness has been described as awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally. Mindfulness is a form of meditation that uses breathing and thought techniques to create an awareness of one’s body and surroundings. Research suggests that mindfulness can have a positive impact on stress, anxiety, and depression.[67] A nonjudgmental approach to each thought, feeling, or sensation that arises is acknowledged and accepted as it is. Mindfulness helps individuals be present in their lives and enhances control over reactions and repetitive thought patterns. It may help with obtaining a clearer picture of a situation and promote more skillful responses.

Compare your default state to mindfulness when studying for an exam in a difficult course or preparing for a clinical experience. What do you do? Do you tell yourself, “I am not good at this” or “I am going to look stupid”? Does this distract you from paying attention to studying or preparing? How might it be different if you had an open attitude with no concern or judgment about your performance? What if you directly experienced the process as it unfolded, including the challenges, anxieties, insights, and accomplishments, while acknowledging each thought or feeling and accepting it without needing to figure it out or explore it further? If practiced regularly, mindfulness helps a person start to see the habitual patterns that lead to automatic negative reactions that create stress. By observing these thoughts and emotions instead of reacting to them, a person can develop a broader perspective and can choose a more effective response.[68]

Try free mindfulness activities at the Free Mindfulness Project.

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- This work is a derivative of Anatomy and Physiology by OpenStax licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Untitled image by Meredith Pomietlo for Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050312118782545 ↵

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6.https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050312118782545 ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- Sissons, C. (2020, July 31). Defense mechanisms in psychology: What are they? MedicalNewsToday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/defense-mechanisms ↵

- Sissons, C. (2020, July 31). Defense mechanisms in psychology: What are they? MedicalNewsToday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/defense-mechanisms ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- Sissons, C. (2020, July 31). Defense mechanisms in psychology: What are they? MedicalNewsToday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/defense-mechanisms ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Stressor. APA Dictionary of Psychology. https://dictionary.apa.org ↵

- Shaw, W., Labott-Smith, S., Burg, M. M., Hostinar, C., Alen, N., van Tilburg, M. A. L., Berntson, G. G., Tovian, S. M., & Spirito, M. (2018, November 1). Stress effects on the body. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/body ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- Kelly, J. F., & Coons, H. L. (2019, October 25). Stress won’t go away? Maybe you are suffering from chronic stress. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/chronic ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020, November 4). Doing what matters in times of stress: An illustrated guide [Video]. YouTube. Licensed in the Public Domain. https://youtu.be/E3Cts45FNrk ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2025, June 9). Providing support for worker mental health. Centers for Disease Control./www.cdc.gov/mental-health/caring/providing-support-for-workers-and-professionals.html ↵

- This work is a derivative of Doing What Matters in Times of Stress: An Illustrated Guide by World Health Organization and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO ↵

- Lowey, S.E.(2015) Nursing Care at the End of Life. Pressbooks. ↵

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050312118782545 ↵

- Amnie, A. G. (2018). Emerging themes in coping with lifetime stress and implication for stress management education. SAGE Open Medicine, 6. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2050312118782545 ↵

- Kandola, A. (2018, October 12). What are the health effects of chronic stress? MedicalNewsToday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323324#treatment ↵

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality ↵

- “yoga-class-a-cross-legged-palms-up-meditation-position-850x831.jpg” by Amanda Mills, USCDCP on Pixnio is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality ↵

- “9707554768.jpg” by Dave Rosenblum is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality ↵

- Puchalski, C. M., Vitillo, R., Hull, S. K., & Reller, N. (2014). Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(6), 642–656. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.9427 ↵

- Rudolfsson, G., Berggren, I., & da Silva, A. B. (2014). Experiences of spirituality and spiritual values in the context of nursing - An integrative review. The Open Nursing Journal, 8, 64–70. https://dx.doi.org/10.2174%2F1874434601408010064 ↵

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality ↵

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality ↵

- Yamada, A., Lukoff, D., Lim, C. S. F., & Mancuso, L. L. (2020). Integrating spirituality and mental health: Perspectives of adults receiving public mental health services in California. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 12(3), 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000260 ↵

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality ↵

- Kandola, A. (2018, October 12). What are the health effects of chronic stress? MedicalNewsToday. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/323324#treatment ↵

- Delagran, L. (n.d.). What is spirituality? University of Minnesota. https://www.takingcharge.csh.umn.edu/what-spirituality ↵

Any internal or external event, force, or condition that results in physical or emotional stress.

The body’s physiological response to a real or perceived stressor.

Traumatic circumstances experienced during childhood such as abuse, neglect, or growing up in a household with violence, mental illness, substance use, incarceration, or divorce.

Reaction patterns used by individuals to protect themselves from anxiety that arises from stress and conflict.

The ability to rise above circumstances or meet challenges with fortitude.

Cognitive and behavioral efforts made to master, tolerate, or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts.

An action, series of actions, or a thought process used in meeting a stressful or unpleasant situation or in modifying one’s reaction to such a situation.

Coping strategies including problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping.

Adaptive coping strategies that typically focus on seeking treatment such as counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy.

Adaptive coping strategies such as mindfulness, meditation, and yoga; using humor and jokes; seeking spiritual or religious pursuits; engaging in physical activity or breathing exercises; and seeking social support.

Ineffective responses to stressors such as avoidance of the stressful condition, withdrawal from a stressful environment, disengagement from stressful relationships, and misuse of drugs and/or alcohol.