3.4 Analyzing Cues, and Generating and Prioritizing Hypotheses

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

Nurses have long been engaged in analyzing the information they gather from patients and then formulating ideas, or hypotheses, about what the data mean. The term ‘diagnosis’ has been applied to this process. The American Nurses Association created standards for this competency, stating, “The registered nurse analyzes assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.”[1] Review the competencies for the Diagnosis Standard of Practice for registered nurses in the following box.

ANA’s Diagnosis Competencies[2]

The registered nurse:

- Identifies actual or potential risks to the health care consumer’s health and safety or barriers to health, which may include, but are not limited to, interpersonal, systematic, cultural, socioeconomic, or environmental circumstances.

- Uses assessment data, standardized classification systems, technology, and clinical decision support tools to articulate actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.

- Identifies the health care consumer’s strengths and abilities, including, but not limited to, support systems, health literacy, and engagement in self-care.

- Verifies the diagnoses, problems, and issues with the health care consumer and interprofessional colleagues.

- Prioritizes diagnoses, problems, and issues based on mutually established goals to meet the needs of the health care consumer across the health-illness continuum and the care continuum.

- Documents diagnoses, problems, strengths, and issues in a manner that facilitates the development of the expected outcomes and collaborative plan.

Analyzing Cues

As discussed in earlier in the Chapter, the Clinical Judgment Model focuses less on the phrase “nursing diagnosis” and more on organizing and linking the cues, or relevant assessment findings, that are part of the patient’s clinical picture. Analyzing data to determine if it is “expected” or “unexpected” or “normal” or “abnormal” for this patient at this time according to their age, development, and clinical status prompt the nurse to consider why these cues are present and whether the cues are of concern. A nursing hypothesis, or diagnosis, is the endpoint of the analysis of cues. It is “a clinical judgment concerning a human response to health conditions/life processes, or a vulnerability to that response, by an individual, family, group, or community.”[3] Nursing hypotheses are customized to each patient and drive the development of the nursing care plan, focusing on the human response to health conditions and life processes. Patients with the same mental health diagnoses will often respond differently and thus have different nursing concerns. For example, two patients may have the same diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder. However, one patient may demonstrate a high risk for suicide whereas another patient may experience impaired nutrition due to lack of appetite. The nurse must consider these different responses when creating an individualized nursing care plan. Recall that nursing diagnoses and hypotheses are different from medical diagnoses and mental health diagnoses. Medical diagnoses focus on medical problems that have been identified by the physician, physician’s assistant, or advanced nurse practitioner. Mental health diagnoses are established by mental health experts, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, and advanced practice psychiatric-mental health nurses, using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5-TR (DSM-5-TR).

Generating Hypotheses

As the assessment data is reviewed, the nurse considers what conditions or processes are resulting in the patient presentation. For example, a patient may be isolative and minimally interactive with others. The nurse considers the psychiatrist’s diagnosis of schizophrenia, the patient’s recent admission for abnormal behaviors, and the patient’s statement that he is hearing voices talking to him. The nurse’s analysis is that the patient is suffering from altered perception of reality related to the schizophrenia. Another patient may exhibit these same isolative behaviors and social isolation related to hopelessness and depressed mood with a DSM-5-TR diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder. The nurse may hypothesize that isolation is a symptom of the depressive disorder, not altered perceptions. With a thoughtful hypothesis, a nurse will be able to determine what additional information is needed and how to prioritize the needs of the patient.

Differentiation from the foundational sciences use of ‘hypothesis’ is salient. Whereas in research, the emphasis in a hypothesis may be on predication, the nursing hypothesis focuses on a proposed explanation for evidence (cues) that is a starting point for action. ‘Hypothesis’ may be a confusing term in nursing care so ‘nursing diagnosis’ is still a useful way to think about organizing patient assessment data.

Prioritization

Prioritization is the process of identifying the most significant problems or hypotheses, and the most important actions to implement based on a patient’s current status. Multiple signs and symptoms, patient requests, and treatment schedules can compete for attention, challenging the nurse to plan focused attention to the highest needs. It is essential that life-threatening concerns and crises are quickly identified and addressed immediately. The steps of the nursing process may be performed in a matter of seconds for life-threatening concerns.

Most patient situations are not at the level of crisis and nurses will have time to prioritize what patient problems need to be addressed first. Generally, any situation where there is risk for self-injury, or injury to others, are high priority. Nurses must recognize cues signaling this risk, apply evidence-based interventions to enhance safety, and communicate effectively with interprofessional team members. Nurses must also balance the needs of multiple patients and will need to factor in time, necessary staff, medical and psychological needs, and risk of worsening conditions. Specific nursing concerns and cues for particular disorders will be considered in later chapters.

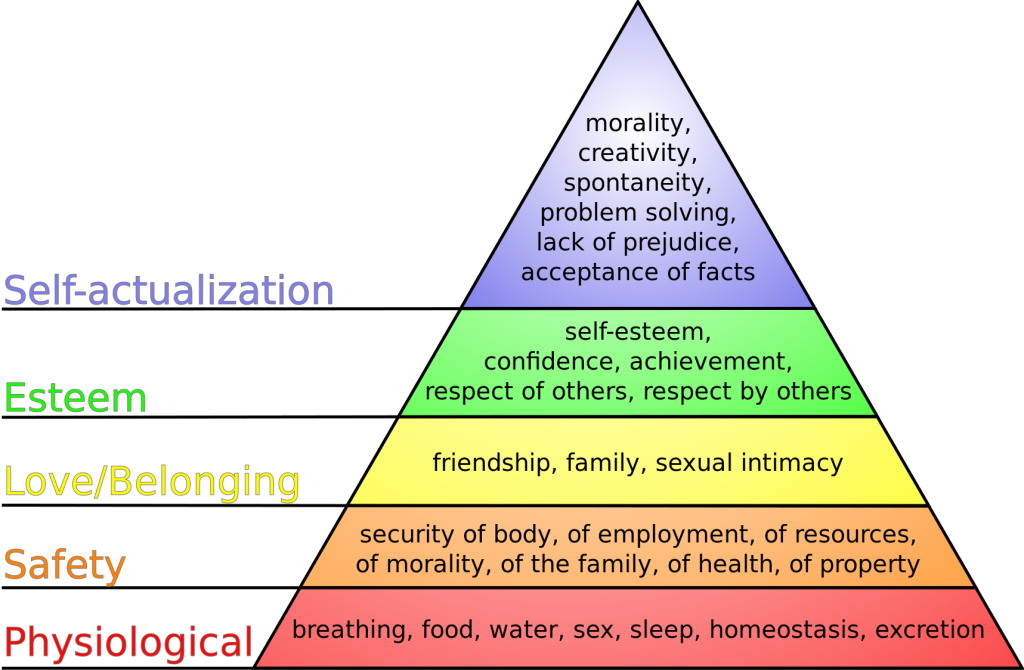

Maslow’s Hierarchy

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs is one theory used to guide patient needs. It posits that people are motivated by five levels of needs: physiological, safety, love, esteem, and self-actualization. The bottom levels of the pyramid represent the priority physiological needs intertwined with safety, whereas the upper levels focus on belonging, esteem, and self-actualization. Physiological needs in Maslow’s model must be met before focusing on higher level needs. [footnote]Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346[/footnote] For example, priorities for a patient experiencing mania are the need for food, fluid, and sleep, as well as controlling the agitation and impulsivity to ensure safety. These needs must be met before focusing on strategies to improve relationships with family and friends, build respect and acceptance for self and others, and engage in activities promoting personal growth. It is important to note that Maslow’s definition of safety is not consistent with that of mental health nurses’ caring for seriously ill patients. Nurses must always prioritize safety needs consistent with survival in addition to physiological needs. Patients who are acutely ill or have chronic mental health disorders often struggle with meeting physiologic needs whereas patients in outpatient or residential treatment settings may have primary needs in the Safety Level. See Figure 3.4[4] for an image of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Common Cues and Hypotheses for Mental Health Conditions

Commonly used nursing cues/diagnoses related to caring for patients with mental health conditions are included in Table 3.3 below. As always, when providing patient care, refer to current, evidence-based practices, and pathways and guidelines established by the facility.

Table 3.4 Common Nursing Diagnoses/Cues Related to Mental Health

| Cues/Analyses | Definition | Selected Defining Assessment Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Risk for Suicide | Susceptible to self-inflicted, life-threatening injury. |

|

| Risk for violence Toward Others | A pattern of verbal and/or physical behaviors that are threatening or physically violent toward others in the environment. |

|

| Ineffective Coping | A pattern of impaired appraisal of stressors with cognitive and/or behavioral efforts that fails to manage demands related to well-being. |

|

| Readiness for Enhanced Coping | A pattern of effective appraisal of stressors with cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage demands related to well-being, which can be strengthened. |

|

| Self-Neglect | A collection of culturally framed behaviors involving one or more self-care activities in which there is a failure to maintain a socially accepted standard of health and well-being. |

|

| Fatigue | An overwhelming sustained sense of exhaustion and decreased capacity for physical and mental work at the usual level. |

|

| Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements | Intake of nutrients insufficient to meet metabolic needs. |

|

| Constipation | Decrease in normal frequency of defecation accompanied by difficult or incomplete passage of stool and/or passage of excessively dry, hard stool. |

|

| Sleep Deprivation | Prolonged periods of time without sustained natural, periodic suspension of relative consciousness that provides rest. |

|

| Social Isolation | Aloneness experienced by the individual and perceived as imposed by others and as a negative or threatening state. |

|

| Chronic Low Self-Esteem | Negative evaluation and/or feelings about one’s own capabilities, lasting at least three months. |

|

| Hopelessness | Subjective state in which an individual sees limited or no alternatives or personal choices available and is unable to mobilize energy on own behalf. |

|

| Spiritual Distress | A state of suffering related to the impaired ability to experience meaning in life through connections with self, others, the world, or a superior being. |

|

| Readiness for Enhanced Knowledge | A pattern of cognitive information related to a specific topic or its acquisition, which can be strengthened. |

|

Sample Case A

During an interview with a 32-year-old patient diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Mr. J. exhibited signs of a sad affect and hopelessness. He expressed desire to die and reported difficulty sleeping and a lack of appetite with weight loss. He reports he has not showered in over a week, and his clothes have a strong body odor. The nurse analyzed this data and created four nursing hypotheses[5]:

- He is at risk for suicide as manifested by reported desire to die. Suicidal thoughts are linked to MDD.

- Hopelessness: The patient is depressed with a sad affect. Hopelessness is a symptom of MDD.

- His nutrition his imbalanced. He has lost weight and reports decreased appetite. These are hallmarks of MDD.

- He is neglecting self-care. His hygiene is poor; he has not showered, and his clothes are odorous. This is consistent with MDD.

The nurse established the top priority as Risk for Suicide and immediately screened for suicidal ideation and a plan using the Patient Safety Screener [6].

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- “Maslow's hierarchy of needs.svg” by J. Finkelstein is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Ackley, B., Ladwig, G., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (12th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- The Patient Safety Screener: A Brief Tool to Detect Suicide Risk – Suicide Prevention Resource Center ↵

Used to prioritize the most urgent patient needs.