7.2 Causes of Depression

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

There are several possible causes of depression, including faulty mood regulation by the brain, genetic vulnerability, stressful life events, medications, and medical problems. Based on current research, it is believed that several of these forces interact to bring on depression.[1]

The Brain and Mood Regulation

In the brain, the hippocampus is smaller in some depressed people, and research suggests that ongoing exposure to the stress hormone impairs the growth of nerve cells in this part of the brain.[2] Activity in the amygdala is higher when a person is sad or clinically depressed. This increased activity continues even after recovery from depression.[3] The hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal glands form the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which governs a multitude of hormonal activities in the body and also plays a role in depression.

There are many types of neurotransmitters that play a role in depression[4]:

- Acetylcholine enhances memory and is involved in learning and recall.[5]

- Serotonin helps regulate sleep, appetite, and mood and inhibits pain. Research supports the idea that some depressed people have reduced serotonin transmission. Low levels of a serotonin by-product have been linked to a higher risk for suicide.[6]

- Norepinephrine constricts blood vessels, raising blood pressure. It may trigger anxiety and be involved in some types of depression. It also seems to help determine motivation and reward.[7]

- Dopamine is essential to movement. It also influences motivation and plays a role in how a person perceives reality. Problems in dopamine transmission have been associated with psychosis, a severe form of distorted thinking characterized by hallucinations or delusions. It’s also involved in the brain’s reward system, so it is thought to play a role in substance abuse.[8]

- Glutamate is a small molecule believed to act as an excitatory neurotransmitter and to play a role in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Animal research suggests that lithium stabilizes glutamate reuptake and smooths out the highs of mania and the lows of depression in the long-term.[9]

- Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is an amino acid that researchers believe acts as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. It is thought to help subdue anxiety.[10]

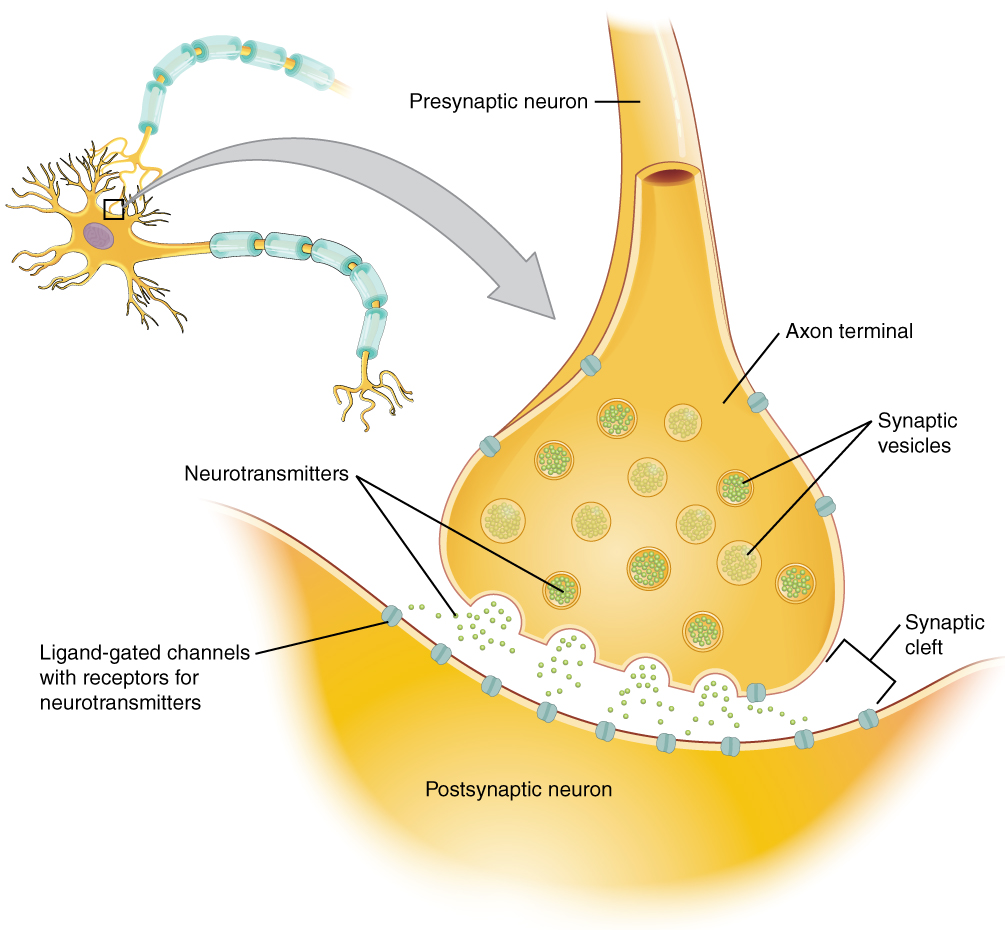

See Figure 7.2[11] for an illustration of neurotransmitter communication between neurons at the synapse. Antidepressants immediately boost the concentration of chemical messengers in the brain (neurotransmitters), but people typically don’t begin to feel better for several weeks or longer. Experts have long wondered why people don’t improve as soon as the level of neurotransmitters increases. New theories explain that antidepressants spur the growth and enhanced branching of nerve cells in the hippocampus (a process called neurogenesis), and mood improves over several weeks as nerves grow and form new connections.[12]

It is well-known that depressive and bipolar disorders run in families. Mood is affected by dozens of genes, and as our genes differ, so does depression. As researchers pinpoint specific genes involved in mood disorders and better understand their functions, it is hoped that treatment for depressive disorders can become more individualized and more successful as patients receive targeted medication for their specific type of depression.[13]

Stressful Life Events

At some point, nearly everyone encounters stressful life events such as the death of a loved one, the loss of a job, the diagnosis of a severe illness, or the end of a significant relationship. Many individuals have also experienced traumatic childhood experiences that continue to affect their coping and functioning into adulthood. Stress triggers a chain of chemical reactions and responses in the body. If the stress is short-lived, the body usually returns to normal. But when stress is chronic or the system gets stuck in overdrive, changes in the body and brain can be long-lasting. Every real or perceived threat to one’s body triggers a cascade of stress hormones that produces physiological changes called the stress response. Normally, a feedback loop allows the body to turn off “fight-or-flight” defenses when the threat passes. In some cases, though, the floodgates never close properly, and cortisol levels rise too often or simply stay high. These elevated cortisol levels can contribute to problems such as high blood pressure, immune suppression, asthma, and depression. Studies have also shown that people who have depressive disorders typically have increased levels of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), the hormone responsible in part readying the body to cope with stress. Antidepressants and electroconvulsive therapy are both known to reduce these high CRH levels. As CRH levels return to normal, depressive symptoms recede. Research also suggests that trauma during childhood can negatively affect the functioning of CRH and the HPA axis throughout life.[14]

Medical Problems and Medications

Certain medical problems are linked to up to 10% to 15% of all depressions. For example, hypothyroidism, a condition where the body produces too little thyroid hormone, often leads to exhaustion and depression, whereas hyperthyroidism (excess thyroid hormone) can trigger manic symptoms. Heart disease has also been linked to depression, with up to half of heart attack survivors reporting feeling blue and many having significant depression. Another example of depression linked to a medical condition is postpartum depression that occurs after pregnancy.[15]

The following medical conditions have also been associated with depression and other mood disorders[16]:

- Degenerative neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and Huntington’s disease

- Cerebrovascular accidents (i.e., strokes)

- Some nutritional deficiencies, such as a lack of vitamins B12, D, and folate as well as low iron

- Endocrine disorders with the parathyroid or adrenal glands

- Immune system diseases, such as lupus

- Some viruses, such as mononucleosis, hepatitis, and HIV

- Cancer

- Erectile dysfunction in men

- Chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, arthritis, diabetic neuropathy, and injury

When considering the connection between health problems and depression, an important question to address is which came first, the medical condition or the mood changes. Stress of having certain illnesses can trigger depression, whereas in other cases, depression precedes the medical illness and may even contribute to it. If depression is caused by an underlying medical problem, the mood changes should disappear after the medical condition is treated. For example, after hypothyroidism is treated, lethargy and depression often lift. In many cases, however, the depression is an independent problem, which means that in order to be successful, treatment must address depression directly.[17]

Symptoms of depression can be a side effect of certain drugs, such as steroids or some types of blood pressure medication. A health care provider can help sort out whether a new medication, a change in dosage, or interactions with other drugs or substances might be affecting an individual’s mood.[18]

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022. January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2019, June 24). What causes depression? Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- “1225_Chemical_Synapse.jpg” by Young, KA., Wise, JA., DeSaix, P., Kruse, DH., Poe, B., Johnson, E., Johnson, JE., Korol, O., Betts, JG., & Womble, M. is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2022, January 10). What causes depression? Harvard Health Publishing. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵

- Harvard Health Publishing. (2019, June 24). What causes depression? Harvard Medical School. https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-causes-depression ↵