Chapter 2: In the Kitchen (Storing and Preparing Food; Preventing Food Waste)

By Aimee Novak, trained chef; Stavroula N. Antonopoulos, MS, RDN; Milad Hasankhani, MSc

Student contributors: Kailah Alvarez, Natalia Rodriguez, Sabrina Reynosa

Introduction

Culinary medicine combines nutrition education and culinary arts to provide the knowledge and skills necessary to sustain a nutritious eating pattern to prevent and treat diet-sensitive disease. Simply instructing people to eat more or less of a food or nutrient is not enough. Sustaining a healthy eating pattern requires ongoing access to nourishing food, including the skills to prepare and store food in a way that maintains its flavor and nutritional value.

Over the years more individuals have increasingly turned to delivery, takeout, and dining out. These trends have been associated with less-nutrient-dense food choices and may be contributing to diminished cooking skills.1-6 Cooking at home provides some control over the amount of sugar, sodium, and saturated fats added to food. Along with effective food storage, these strategies can significantly affect the nutrient density of meals while helping to reduce food waste.1-6

This chapter presents strategies for safe and effective food storage and preparation to maximize the health benefits of food and minimize food waste, which are central to sustaining a healthy eating pattern, especially on a limited budget. Prior to reading this chapter, we recommend reviewing the information in chapter 1 on purchasing nutritious foods.

General Food Safety Principles

Food safety is an essential aspect of maintaining good health and preventing foodborne illnesses. The following subsections discuss general food safety principles everyone should be aware of.1-3

Clean

Cleaning and sanitizing are essential steps in preventing the spread of harmful bacteria and viruses.7 These include regularly cleaning and sanitizing all tools, equipment, and work surfaces used in food preparation. Tools and equipment should be washed with hot, soapy water after each use. Wash hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds before and after handling food, after using the bathroom, and after touching pets.7

In the following set of interactive activities, select the > to read additional information, then take the self-quizzes to test your knowledge:

Separate

Separate raw meat, poultry, seafood, and eggs from other foods to prevent cross contamination. Use separate cutting boards and utensils for each type of food.

Cook

Cooking food to the proper temperature is essential to kill harmful bacteria and prevent foodborne illness (see Table 2.1). Use a food thermometer to ensure that meat, poultry, seafood, and other foods are cooked to the recommended temperature.7

Table 2.1. Safe Food Handling and Preparation Temperatures8

| Product | Minimum internal temperature and rest time |

|---|---|

| Beef, pork, veal and lamb steaks, chops, roasts | 145 °F (62.8 °C) and allow to rest for at least 3 minutes |

| Ground meats | 160 °F (71.1 °C) |

| Ground poultry | 165 °F (73.9 °C) |

| Ham, fresh or smoked (uncooked) | 145 °F (62.8 °C) and allow to rest for at least 3 minutes |

| Fully cooked ham (to reheat) | Reheat cooked hams packaged in USDA-inspected plants to 140 °F (60 °C) and all others to 165 °F (73.9 °C). |

| All poultry (breasts, whole bird, legs, thighs, wings, ground poultry, giblets, and stuffing) | 165 °F (73.9 °C) |

| Eggs | 160 °F (71.1 °C) |

| Fish and shellfish | 145 °F (62.8 °C) |

| Leftovers | 165 °F (73.9 °C) |

| Casseroles | 165 °F (73.9 °C) |

Chill

Chill perishable foods promptly to prevent the growth of harmful bacteria. Keep the refrigerator temperature at or below 40 °F (4 °C), and the freezer at 0 °F (−18 °C).7-12

In addition to these general principles, it is also important to be aware of food recalls and to check for any recalls that may affect the safety of the food being consumed. Consumers can check the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Recalls, Market Withdrawals, & Safety Alerts webpage for a current list.13

Finally, it is important to understand the signs and symptoms of foodborne illnesses, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever. If these symptoms occur after consuming food, it is important to seek medical attention promptly.

Food Storage Guidelines

To prevent foodborne illnesses and maintain food quality and nutrition, store perishable items such as meat, poultry, seafood, and dairy products in the refrigerator at or below 40 °F (4.4 °C). Keep raw meat separate from other foods to avoid cross-contamination. Store nonperishable items in a cool, dry place away from direct sunlight. Regularly clean and sanitize storage areas to prevent bacteria growth and contamination.

Refrigeration

Temperature control

Proper refrigerator storage slows microbial growth and controls perishable food quality by holding foods at appropriate temperatures.9 Perishable foods are those likely to spoil, decay, or become unsafe to consume if not kept refrigerated at 40 °F (4.4 °C) or below, or frozen at 0 °F (−17.8 °C) or below. Examples of foods that must be kept refrigerated for safety include meat, poultry, fish, dairy products, and all cooked leftovers. Refrigeration can slow bacterial growth.

It is recommended to use a refrigerator thermometer along with the internal thermometer of the refrigerator to measure temperature accurately. A refrigerator thermometer is a small, freestanding gadget that can be used to measure the temperature of both the refrigerator and freezer. It is important to use thermometers that are designed to function in cold temperatures to obtain precise temperature readings. You can purchase these thermometers online or from most hardware stores. They are simple to use.

Adjusting the temperature settings of your refrigerator or freezer is usually a straightforward process because most have temperature controls located inside of them. Consult the manual for specific temperature adjustment instructions and remember that an adjustment period may be necessary for temperatures to stabilize when changing the setting. To minimize temperature fluctuations, you should reduce the number of times you open the refrigerator during warmer weather.9

Storage organization

An organized refrigerator is essential to find what you need quickly. To help with organization, adjustable shelves, crispers, and meat and cheese drawers are useful storage options. Tempered glass shelves are durable and easy to clean, and some refrigerator models have pullout capabilities for easier access.

For optimal storage of fruits and vegetables, consider using sealed crisper drawers with customizable humidity settings to ensure maximum freshness. Lastly, an adjustable-temperature meat drawer will help you maximize the storage time for your meats and cheeses.

To keep your food safe from contamination, store all raw meat, poultry, and seafood in sealed containers or wrap them securely in a leak-proof container with a lid to prevent cross-contamination. Labeling and dating food items as you prepare the item for storage will prevent food waste and naturally occurring spoilage bacteria.

Cleaning and Maintenance

- Maintaining the cleanliness and safety of your refrigerator is important; regularly check for expired or spoiled food items and dispose of them properly. Refer to FoodSafety.gov’s Cold Food Storage Chart guidelines for storing food in the refrigerator. The short time limits for home-refrigerated foods will help keep them from spoiling or becoming dangerous to eat.

- Wipe up spills promptly with hot, soapy water, and dispose of expired perishables weekly.

- Consider keeping an open box of baking soda on a shelf to prevent unpleasant odors.

- When cleaning the refrigerator, it is best to use mild liquid dishwashing detergents and cleaners specifically designed for appliances and to avoid harsh chemicals that could damage the interior.

Check your understanding by completing the following interactive activities:

Reduces food waste:

Improves food safety:

Maximizes space:

Saves money:

Learn more about food-safe shopping and storage from the FDA:

Dry Storage

Storing nonperishable food properly in a pantry will help save money, reduce food waste, and ensure the safety and freshness of food. The pantry is ideal for storing shelf-stable foods, such as canned goods, baking ingredients, and spices. Nonperishable products include jerky, country hams, most canned and bottled foods, rice, pasta, flour, sugar, spices, oils, and foods processed in packaging solutions that maintain high product quality during shelf life. These products do not require refrigeration until after opening.

Not all canned goods are shelf stable. Some canned foods, such as canned ham and seafood, are unsafe at room temperature. These will be labeled “Keep Refrigerated.”

Here are some tips to help you store your pantry items correctly:

- Check each food item’s expiration or “Best if Used By/Before” date for storage requirements to maintain quality. Some foods, such as dairy products, meat, and eggs, must be refrigerated at all times, whereas other foods, such as canned goods and dry foods like flour, sugar, and pasta, can be stored in a cool, dry place.

- Prevent waste by rotating your stock. Store newly purchased items behind older ones and use the oldest items first. This technique helps prevent food spoilage and ensures the consumption of the items before the expiration date.

- Learn more about expiration dates in “Food Safety Information: Food Product Dating [PDF].”

- Organize your pantry to make meal planning easier and prevent overbuying. Group similar items, such as canned vegetables, fruits, and soups, and baking supplies such as flour and sugar. Keep frequently used items at eye level or within reach and use clear containers or labels to identify the contents.

- Use appropriate containers to ensure food safety. To keep dry goods such as cereal and pasta fresh, use airtight containers to prevent moisture and pests from getting inside. It is best to use glass or plastic containers for liquids like oils and vinegar. Avoid using containers that are not food-safe and could potentially cause contamination.

- Keep your pantry clean and dry, and regularly clean and dust the shelves. Avoid storing food in damp areas and check for signs of pests, such as droppings or chewed packaging, to ensure your pantry stays clean, safe, and free from potential health hazards.

Building and Organizing a Pantry

Keeping a well-stocked pantry and understanding ingredients are the building blocks for creating tasty and nutritious meals. Including versatile ingredients in your pantry can help increase meal options and stretch your food dollars. In addition, purchasing essential pantry items (e.g., fruits, vegetables, and proteins, plus oils, herbs, spices, whole grains, pulses, and legumes) provides the foundation for nutrient-dense meals.

Organizing your pantry into “zones” helps you find ingredients easily. Zones could include seasonal ingredients, flavor profiles (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, spicy), global flavors (e.g., Italian, Thai, Indian, Chinese), or cooking categories (e.g., baking, weeknight meals, breakfast, or most-used items).

Essential Pantry Items or Staples

Fruits and Vegetables

Think seasonally and shop weekly. Locally grown, fresh seasonal vegetables taste better and are generally less expensive than items that might be out of season. Consult a local growing guide to see what fresh produce may be available in your area or use alternative sources such as frozen or canned fruits and vegetables. Select low-sodium canned vegetables and fruit canned in natural fruit juice. Consider buying frozen fruits and vegetables without added salt or sauces to reduce sodium intake.

Proteins

Protein-rich foods include fresh, canned, or frozen lean meats, poultry, fish, and seafood. If you are looking for meat alternatives, try pulses, eggs, nuts (e.g., almonds, walnuts, pecans), seeds (e.g., chia seeds, flaxseeds, sunflower seeds), or plant-based proteins such as tofu, tempeh, seitan, quinoa, and bean pastas (e.g., chickpeas, black beans, red lentils).

Low-cost pantry staples such as beans, legumes, nuts, and seeds are easy to store and versatile for a variety of recipes. Using plant-based proteins can have important health benefits, such as reducing the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes.

Nutrient-Dense Fats and Oils

Knowing the health benefits of the oils you are cooking with can help determine which oil to use. Consider the oil’s flavor characteristics when selecting, because some have a neutral flavor and others have more distinct flavors. Also consider unique cooking properties such as smoke point. Examples of nutritious fats include avocado, nuts, seeds, seed oils, olive oil, coconut oil, avocado oil, canola oil, nut oils, and nut butters.

Herbs and Spices

Herbs and spices are often used in cooking as flavoring or seasoning. Herbs are plants with edible leaves, seeds, or flowers. Spices are derived from roots, seeds, bark, buds, and berries. The health benefits of herbs and spices include helping to reduce excess salt and fat while providing flavor and phytonutrients, such as bioactive molecules, tannins, alkaloids, phenolic diterpenes, flavonoids, and polyphenols.14

Examples of popular cooking herbs include basil, oregano, thyme, mint, cilantro, rosemary, and sage; examples of popular spices include cinnamon, turmeric, ginger, cumin, coriander, garlic, chili powder, and cloves.

Whole Grains and Pulses

Keeping a variety of grains and pulses in your pantry provides a foundation for nutritious meal options because these foods are rich sources of protein, iron, vitamins (especially folate and other B vitamins), and antioxidants, and an excellent source of fiber and potassium. Examples of whole grains include brown rice, whole-wheat pasta, quinoa, barley, and millet.15,16 Pulses are the dry, edible seeds of legumes, which include lentils, chickpeas, beans, and dry peas, among others.

The importance of cooking with whole grains as part of a nutritious eating pattern is their nutritional value.15 Whole grains contain a variety of vitamins, minerals, fiber, protein, antioxidants, and other phytochemicals.15 Milled or refined grains have less nutritional value than unrefined grains because the nutrients in refined grains typically are stripped during processing.

General cooking methods for whole grains include the absorption, boiling (pasta method), risotto, and pilaf methods. To learn more about cooking whole grains, visit the following links below or refer to Preparing Whole Grains and Pulses within the Principles of Cooking section later in the chapter:

- Grains (US Department of Agriculture’s [USDA] MyPlate)

- Delicious Whole Grain Recipes (Oldways Whole Grains Council)

- Whole Grain Cooking Tips [PDF—English] (Oldways Whole Grains Council)

- Whole Grain Cooking Tips [PDF—Spanish] (Oldways Whole Grains Council)

Pro Tip: Remember, soaking grains overnight accelerates cooking and improves the absorption of liquid and seasonings. If toasting, to ensure the toasting process isn’t disrupted, don’t rinse the grains. Toast grains using dry heat in an oven or skillet until they are golden brown, stirring occasionally.

Pulses provide a variety of nutrients. They are also an excellent gluten-free protein option. For procedures of preparing pulses, refer to the Cooking Methods section in this chapter.

Read Pulses Nutrition Facts and watch this video from USA Pulses to learn more about pulses:

Snacks and Sweets

There are many advantages to having a variety of nutritious snacks in your pantry. The right snack can provide not only nutrients but also help curb appetite between meals and boost energy throughout the day. Some examples of nutritious snacks include dark chocolate, dried fruits, nuts, and popcorn.

Follow these links for more snack information:

- Tasty Popcorn Toppings (University of Arizona College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Cooperative Extension: Tucson Village Farm)

- Hacking Your Snacks (USDA’s MyPlate)

- Culture and Food (USDA’s Nutrition.gov)

Basic Principles of Smell and Taste

Smell (or olfaction) and taste (or gustation) are 2 of the 5 primary senses that play a crucial role in the human experience of the world around us. Understanding taste and smell helps us understand various ingredients’ flavors, aromas, and their interactions in the context of food preparation and food preferences.

Taste and smell are the primary senses that play a vital role in experiencing different flavors. By comprehending the science behind taste and smell, we can mix ingredients that complement each other, enhance certain flavors, or create contrasts to achieve the desired taste profile. Furthermore, understanding taste and smell helps when developing new recipes or modifying existing ones by experimenting with different ingredient combinations and adjusting the flavors based on these senses.

Knowing the flavor profiles can also help in finding alternative ingredients or substitutions for certain flavors to prepare safe and enjoyable dishes for everyone. This section delves into the biological mechanisms of smell and taste, which together shape our fundamental experience of food’s flavor.17-20

Flavor encompasses both taste and odor, and the olfactory system plays a vital role in its perception. Odor molecules can reach the olfactory receptors through the retronasal and orthonasal pathways. In the retronasal pathway, odors are perceived when chewing and swallowing propel odorants from the mouth to up behind the palate and into the nose. Although the actual contact and receptor activation occurs at the olfactory mucosa, this sensation is perceived as originating from the mouth. The brain processes information from various regions when food in the oral cavity interacts with the olfactory mucosa.

The orthonasal pathway, on the other hand, involves odors encountered in the environment and perceived through inhalation of odor-containing air, not originating from the mouth. Certain medical conditions—such as allergies, sinusitis, and COVID-19—can affect the sense of smell, leading to changes in appetite and food preferences.18-20

Tastes

Sweet

The perception of sweetness is primarily elicited by the presence of sugars and certain amino acids in food. It is thought that the preference for sweet tastes evolved to help identify energy-rich foods, like those with glucose, which provide important fuel for the body.19,20

Consuming too much added sugars can lead to health problems, such as excess body weight, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease. The American Heart Association recommends limiting added sugar intake to no more than 6 teaspoons per day (25.2 g) for women and 9 teaspoons per day (37.8 g) for men.21

Sour

Sourness or tartness is characteristic of the taste of acids and is induced by the presence of hydrogen ions in food. From an evolutionary standpoint, the ability to perceive sourness is thought to have developed as a means to identify spoiled or rotten foods, which could be detrimental to health.21,22 However, it is imperative to note that not all foods with a sour taste are harmful; for example, vinegar, lemon juice, cranberries, yogurt, and buttermilk are safely consumable. Sourness can stimulate digestion and aid nutrient absorption, but consuming too much acid can exacerbate gastroesophageal reflux disease and also can erode tooth enamel over time.23

Salty

The salty taste is predominantly caused by the presence of sodium chloride in food, although other mineral salts can also elicit this taste. Sodium is a vital element for maintaining electrolyte and fluid balance in the human body. Consequently, the ability to taste saltiness is thought to have evolved to ensure sufficient intake of sodium.20,24

Examples of foods that are typically considered salty include soy sauce, processed meats, preserved olives, and french fries. Consuming too much salt can increase the risk of hypertension, stroke, and fluid retention, which can be problematic with heart failure and/or end-stage renal disease.

The American Heart Association recommends limiting sodium intake to no more than 2,300 mg/d (~1 measured teaspoon), or 1,500 mg/d for people with high blood pressure, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease.25

Bitter

Bitterness is a taste sensation that can be attributed to many molecules, many of which are found in plant-based foods. It is widely believed that the human ability to taste bitterness evolved as a defense mechanism to recognize and avoid toxic substances present in certain plants.20,26,27 Despite this, not all bitter substances are harmful, and bitterness can be appreciated in moderation or when combined with other tastes, as in coffee, wine, dark chocolate, chicory, endive, and certain leafy greens.

Umami

Umami, often described as a savory or meaty taste, is elicited by foods rich in amino acids, especially glutamic acid and aspartic acid.18-20 Umami is thought to play a role in appetite regulation and the efficient digestion of proteins.18-20,28 Foods that are rich in umami include tomatoes, mushrooms, cheeses, and meats.28

Assembling Tools and Equipment

Creating nutrient-dense meals requires the right ingredients and a few essential tools to make the entire process flow smoothly. Use this checklist to help you identify which essential tools you currently have and which ones you may want to consider adding to your kitchen. It is not necessary to have all the equipment listed here, but it may be helpful to have a few from each category to help make your cooking easier.

Next, test your understanding with this series of interactive activities. Use the circles or arrows at the bottom to advance through the activities:

Principles of Food Preparation

Understanding the Recipe

To achieve culinary success, it is essential to have a solid comprehension of the recipe you are following. Start by carefully reading the instructions, verifying that you have all the required ingredients and tools, and comprehending the proper order, time, and temperature specifications. Familiarity with fundamental cooking techniques, such as chopping and sautéing, also can prove beneficial when executing a recipe. A thorough understanding of a recipe guarantees a more seamless cooking experience and heightens the likelihood of a delicious outcome.

To properly execute a recipe, it is recommended to follow these simple steps:

- Read the entire recipe to understand the methods and techniques to gain a thorough understanding of the cooking processes and equipment required for the recipe.

- Familiarize yourself with the units of measurement used in the recipe and convert them if necessary.

- Reread the recipe, focusing on the step-by-step instructions provided. Pay attention to the order in which ingredients are added and the cooking techniques required at each stage. Begin preparing the items that require the longest cooking time first.

- Determine if the recipe suggests any changes or substitutions for those with dietary restrictions or preferences.

- Plan your prep and cooking schedule based on the recipe.

Pro Tip: Remember to consider healthy cooking methods. Look for keywords such as “grilling,” “roasting,” “steaming,” or “sautéing.” These methods can make your meals delicious and nutritious.

Gathering and Prepping Ingredients

The next step is to gather and prep the ingredients. Begin cooking only after you clearly understand the recipe and have completed your mise en place. Follow the instructions step by step and refer to the recipe as needed to ensure you are on track.

Measuring Ingredients

- Measuring weight and volume are not equivalent. One cup does not equal the same weight for all ingredients; those units of measure cannot be used interchangeably.28,29

- Weight measures heaviness (e.g., grams, ounces, or pounds). Volume (height multiplied by width by volume) measures filled space (e.g., fluid ounces, teaspoons, tablespoons, cups, pints, quarts, gallons, liters).28,29 To clarify, ounces measure weight, and fluid ounces measure volume (liquids). For example, one-half cup of uncooked rice weighs more than one-half cup of cooked rice.

- Ingredients are weighed using different scales, which are primarily used by commercial operations to optimize precision and reduce waste.28,29 For instance, spring-type scales are used to measure dry ingredients, such as grains and beans. A baker’s scale is used to measure baking ingredients.28 For home use, a digital scale serves the same purpose. However, some recipes do not require scales, and measuring cups and spoons are suitable for measuring the ingredients.

Measuring Dry Ingredients

- Use flat-topped measuring cups.

- If less than one-quarter or one-eighth cup is to be measured, use flat-topped measuring spoons.

- Level the contents with a knife, with the measuring cup on a flat surface.

- Sifting flour with dry ingredients, such as salt or baking powder, promotes more even distribution.

Measuring Liquids

Precise liquid measurements can make a difference because recipes can easily turn out too dry or mushy without proper liquid amounts.

- Use a transparent, graduated cup with a pour spout.

- Measure the volume at eye level.

Basic Knife Cuts

To achieve even cooking and consistent texture in your dishes, it is important to have basic knife skills. Whether dicing vegetables for a stir-fry or julienning carrots for a salad, mastering basic knife cuts will enhance your culinary skills and efficiency, and save you time. The following videos from University of Arizona Yavapai County Cooperative Extension offer a quick and safe guide on preparing your ingredients for cutting and examples of how to perfect some standard cutting techniques:

Principles of Cooking

Cooking methods can affect the nutrient profile of food positively or negatively. For example, cooking meats or fish until they are well done, charred, or browned could have similar negative effects on nutrient composition. 28,30 Likewise, cooking red meat at high temperature (see Table 2.3) can promote oxidation of proteins and charring, which has been associated with an increased risk for colon cancer.31

Deep-fried foods contain higher levels of fats that may lead to several adverse health conditions. Frying also promotes a chemical composition change in food, as well as lipid oxidation. To reduce fat intake while preserving nutrients and the health benefits of certain foods, select low-fat cooking methods, such as steaming, baking, boiling, grilling, or air frying.

The activities31-35 below explore the perceptions of flavors as they relate to temperature, thickness, taste, and other factors:

Learn more about the cooking methods in Tables 2.2 and 2.3.

Table 2.2. Types of Heat Used for Cooking28

| Heat transfer type | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conduction | Heat transferred to food through direct contact with metal (e.g., pan) and flame or electric coil. | Conduction oven, heating pan on stove, melting butter in saucepan |

| Convection | Heat transferred to food via moving liquid (water or fat) or air currents through and/or around food. | Convection ovens, simmering, steaming, frying |

| Induction | Heat transferred as particles’ waves moving out from their source without direct contact. | Flat-surfaced ranges (electric coil) |

| Radiation | Electromagnetic wave | Broiling, grilling, microwaving, heat lamps |

Table 2.3. Types of Cooking28

| Cooking method | Description | Temperature range | Ideal foods |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Dry heat preparation uses air, fat, radiation, metal, conduction, or convection. |

|||

|

Broiling |

Food cooked under intense heat | 500-550 °F (260-288 °C) | Tender meats, steak (rib eye, strip loin, tenderloin), fish fillets, poultry, vegetables |

|

Grilling |

Food cooked over or above intense heat | 500-550 °F (260-290 °C) | Burgers (ground beef or turkey), hot dogs, chicken breasts (boneless, skinless), vegetables |

|

Roasting |

Often used for baking meat and poultry

|

325-425 °F (163-218 °C) | Whole chicken, turkey, beef (rib roast, sirloin roast), pork (loin roast), vegetables |

|

Baking |

Heating food via hot air within an oven |

300-425 °F (149-218 °C) Average temperature: 300 °F (149 °C) |

Bread, pita, naan, cookies, casseroles, cakes |

|

Sautéing/stir frying |

Uses least amount of oil over moderately high heat | 300-350 °F (149-180 °C) | Thin cuts of meat (chicken cutlets, pork tenderloin), fish fillets, vegetables |

| Pan-frying Video: Pan Frying |

Meat or other foods cooked in a moderate to generous amount of fat in very hot frying pan. Food is not completely submerged in fat. | 300-350 °F (149-177 °C) | Chicken or pork chops (lean cuts), fish fillets, vegetables |

| Deep-fat frying Video: Deep Frying |

Complete submersion in liquid fat at high temperature | 350-450 °F (177-232 °C) | Chicken wings (higher-fat cuts), french fries, doughnuts, fish, chips |

| Moist heat preparation uses water or steam. Video: The Science Behind Energy Transfer in Liquids |

|||

| Parboiling Video: How to Parboil Tomatoes Properly |

Partially cook food by boiling or used for preparing foods for another final cooking method. |

160-212 °F (71-100 °C) |

Potatoes, carrots, beets, tough cuts of meat (beef brisket, pork shoulder) |

| Blanching Video: How to Blanch Vegetables |

Food is briefly immersed in water. This is done before freezing foods for enzyme inactivation. |

160-212 °F (71-100 °C) |

Vegetables (broccoli, green beans, asparagus), fruits (peaches, tomatoes), seafood (lobster, shrimp) |

| Pressure cooking Video: The Science Behind Pressure Cookers |

Food is cooked faster due to pressure increase (atmospheric pressure) and cooking temperature (boiling point) increases | 235-250 °F (113-121 °C) | Tough cuts of meat (beef chuck, pork shoulder), beans, rice, stews, soups |

| Scalding Video: How to Scald Milk |

Term used for milk. Formation of large, stationary bubbles on bottom and sides of pot, bubbles do not break surface. Over medium-high heat. |

150-160 °F (66-71 °C) |

Dissolving sugar in hot milk; melting butter and chocolate; mixing flour in without lumps; destroys bacteria in unpasteurized milk |

| Poaching Video: Poaching |

Relatively motionless bubbles that appear on the bottom of the pan or pot |

160-175 °F (71-79 °C) |

Eggs, fish fillets, chicken breasts (lean cuts) |

| Simmering Video: How to Simmer |

Right below boiling point with gently rising bubbles that barely break the surface |

>180 °F |

Soups, stews, beans, tough cuts of meat (beef chuck, pork shoulder), rice |

| Boiling Video: What Is Boiling? An Introduction |

Bubbles rapidly | 212 °F (100 °C) at sea level |

Pasta, soup, rice, sauces, tougher-textured vegetables, beans, seafood |

| Steaming Video: Steaming |

Food cooked via direct contact with steam produced | 212-250 °F (100-121 °C) | Vegetables (retain nutrients, taste, color, and texture), fish fillets, chicken breasts (lean cuts) |

| Combination heat | |||

|

Braising |

Food simmered in small amount of liquid, using larger cuts of vegetables and meat | 250-325 °F (121-163 °C) | Tough cuts of meat (beef brisket, pork shoulder), chicken legs (thighs and drumsticks) |

|

Stewing |

Chopped ingredients simmered in moderate amount of liquid and covered | 185-205 °F (85-96 °C) | Tough cuts of meat (beef chuck, lamb shoulder), vegetables |

|

Source: Brown AC. Understanding Food: Principles and Preparation. 6th ed. Cengage Learning; 2015. This table is included on the basis of fair use. |

|||

Learn more about various cooking methods by watching this video from NutritionFacts.org:

“The Best Cooking Method” by Michael Greger, MD, FACLM licensed under CC-BY-NC 4.0

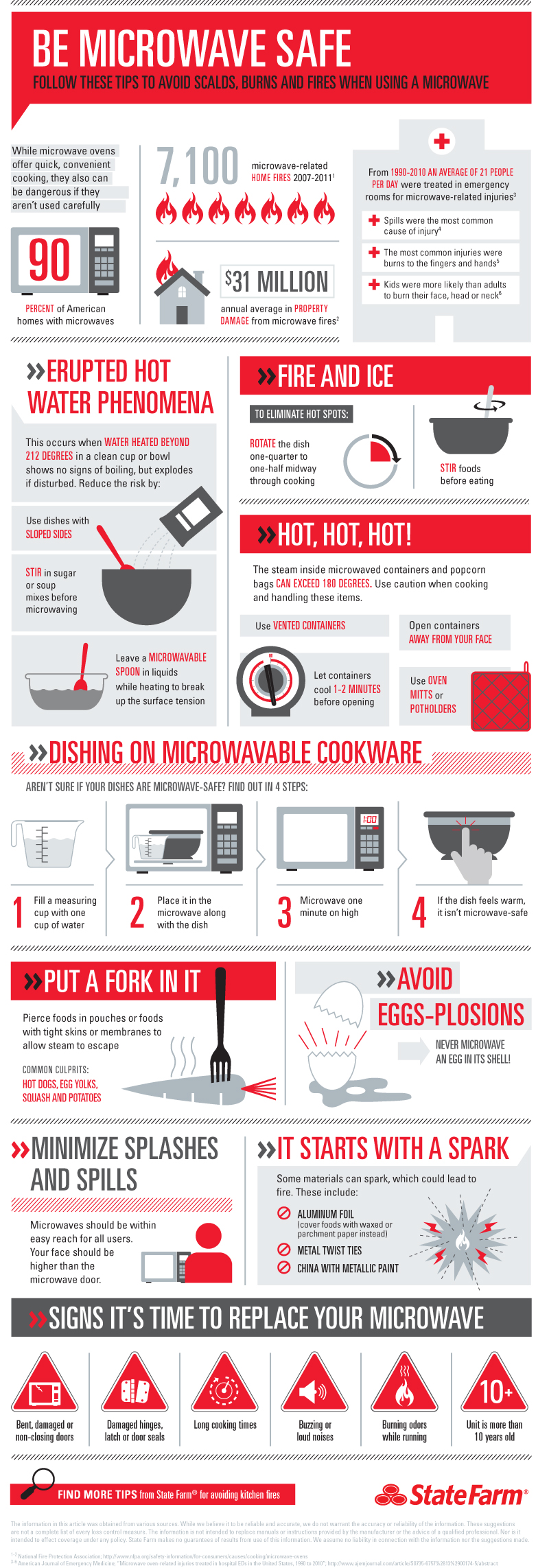

Microwaving

Microwaving is a combination of moist- and dry-heat methods but is often categorized as a moist-heat method because it involves water. However, microwaves are a type of radiation (a dry-heat method) that excites (heats) the water molecules within food, which causes the food to warm up. Because microwaves use radiation, it is important to use microwave-safe cookware only or else damage, fires, and physical (nonfood particle) contamination from the container may occur.28

In a microwave, food can be steamed by covering the food with plastic wrap. Sometimes, microwaves are used for thawing, and then the thawed food is cooked immediately afterward.28 For cooking, not all meats (e.g., thicker cuts or whole roasts) can be microwaved, because the waves only go through to approximately 0.5 to 2 inches (0.1-0.5 cm).28 Therefore, it is unsafe and a food safety concern to cook meat in microwaves. See Figure 2.16 for microwave-safe tips and statistics.

Preparing Whole Grains and Pulses

Basic instructions for preparing all types of whole grains28:

Basic instructions for preparing all types of pulses:

Pro Tip: It takes the same amount of time to prepare lentil and split peas as it takes to prepare certain varieties of pasta and rice! For more information on how to cook pulses, see Get Cooking and Nutrition Professionals from USA Pulses.

Impact of Cooking on Nutrients

Water-soluble vitamins (i.e., B vitamins and vitamin C) are more susceptible to nutrient degradation than fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) because water loss begins as soon as the produce is picked from its plant source. Temperature management is most important for preventing nutrient loss. During storage, vitamins C losses are accelerated with higher temperatures and longer duration in storage contains and units (see Table 2.4).36-39

When cooking with water, water-soluble vitamins degrade and are lost in the water with heat. When cooking with oil, fat-soluble vitamins degrade into the fat.36-39 A rule of thumb is to consume the water or oil that the food is cooked in to still receive more of the vitamins that degraded from the food.

Many studies indicate that vitamin C is easily lost during cooking, due to its water solubility and temperature sensitivity. Higher cooking temperatures and longer cooking times particularly increase the loss of vitamin C. Although the nutrient loss varies depending on the vegetable, steaming or microwaving with minimal or no water is ideal to maintain nutrient integrity; and steaming and or stir-frying helps preserve the vitamin profile of vegetables, for this same reason.36-39

Table 2.4. Storage Temperature’s Impact on Vitamin C Degradation37

|

Storage temperature for 7 days |

Vitamin C loss |

|---|---|

| Green peas stored at 4 °C (39 °F) | 15% |

| Green beans stored at 4 °C (39 °F) | 77% |

| Broccoli stored at 0 °C (32 °F) | 0% |

| Broccoli stored at 20 °C (68 °F) | 56% |

Research Study at a Glance

In one study, boiling water rendered almost all samples deficient in vitamin C, and nutrient retention ranged from 0% to 73.86%; vitamin C loss was greatest in boiled chard. According to the retention rate of the samples, which ranged from 57.85% to 88.86%, blanched spinach showing the highest loss. The retention of vitamin C in all vegetables except broccoli was reduced from 0% to 89.24% by steaming. Vitamin C levels were not significantly affected by microwave cooking, and, when steamed or microwaved, spinach, carrots, sweet potatoes, and broccoli had high retention rates (>90%). Increased levels of vitamin C are associated with less water use and shorter cooking times.38

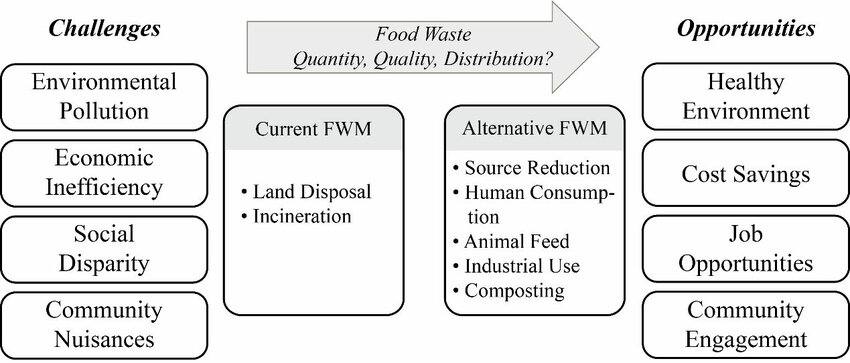

Food Waste

Preventing Edible Food Waste

According to the FDA, food waste in the United States is estimated to range from between 30% and 40% of the food supply. These figures, based on estimates from the USDA Economic Research Service of 31% food loss at the retail and consumer levels, corresponded to approximately 133 billion pounds and $161 billion worth of food in 2010.40

Finding ways to minimize this loss and waste could foster many benefits to society, including reducing food insecurity, saving money, conserving energy, and mitigating climate change by lowering greenhouse gas emissions from rotting food in landfills.40

Land, water, labor, energy, and other inputs are used in producing, processing, transporting, preparing, storing, and disposing of discarded food. Top contributors to food waste include spoiled produce and meat, uneaten leftovers, and a misunderstanding of “best by” dates.40

One reason for premature food waste is the food and product dating, including the “best if used by/before,” “sell by,” “use by,” and “freeze by” dates, which prompt consumers to throw away food items before their true expiration date (when they are no longer safe to consume).

To avoid discarding food prematurely or before its expiration date, read more from the USDA about Food Product Dating. For a complete guide on food storage and safety to prevent food waste, Food Keeper was created by the USDA, Cornell University, and the Food Marketing Institute.

Food Keeper

Access the Food Keeper tool on the web or download it on your smartphone:

Watch this video from the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension in Yavapai County on safely storing items that can spoil:

Product labeling, shopping, ordering, labeling foods at home, and storage also play a role in food waste. If there are flaws in these systems, then food waste is inevitable. Food waste can also be used to create compost or feed animals.40-42 Wholesome food that will not be sold or consumed before expiration can be donated to food banks and pantries, further reducing food waste.42

Preventing Food Packaging Waste

Which items are considered recyclable depends on local regulations. Typically, cardboard, paper, food boxes, beverage cans, glass bottles, jars (glass and plastic), jugs, and plastic bottles and caps are recyclable. Plastic bags and wraps are also recyclable, but they cannot be recycled in curbside bins.44 Learn more about your local recycling options at Earth911 or Recycle Nation. For more information, see How Do I Recycle Common Recyclables from the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Key Takeaways

- Practicing the 4 steps—Clean, Separate, Cook, Chill—is crucial for preventing the spread of harmful bacteria and viruses and ensuring food safety. It is also important to stay informed about food recalls and recognize the signs of foodborne illnesses so prompt medical attention can be sought.

- Smell and taste are integral parts of our sensory experience, with the olfactory system playing a crucial role in perceiving flavor through both the retronasal and orthonasal pathways.

- Mastering fundamental cooking methods and using proper knife techniques ensure you can prepare a variety of foods safely and efficiently.

References

- US Department of Agriculture, US Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th ed. December 2020. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov

- Mills S, Brown H, Wrieden W, White M, Adams J. Frequency of eating home cooked meals and potential benefits for diet and health: cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):109. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0567-y

- McGowan L, Pot GK, Stephen AM, et al. The influence of socio-demographic, psychological and knowledge-related variables alongside perceived cooking and food skills abilities in the prediction of diet quality in adults: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):111. doi:10.1186/s12966-016-0440-4

- Saksena MJ, Okrent A, Anekwe T, et al. America’s eating habits: food away from home. Economic Information Bulletin No. (EIB-196). US Department of Agriculture; 2018:26.

- Smith LP, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Trends in US home food preparation and consumption: analysis of national nutrition surveys and time use studies from 1965–1966 to 2007–2008. Nutr J. 2013;12:45. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-12-45

- Raber M, Chandra J, Upadhyaya M, et al. An evidence-based conceptual framework of healthy cooking. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:23–28. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.05.004

- About four steps to food safety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 24, 2023. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/food-safety/prevention/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/keep-food-safe.html

- Safe minimum internal temperature chart. Food Safety and Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture. May 11, 2020. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/safe-temperature-chart

- Appliance thermometers. Food Safety and Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture. August 8, 2013. October 26, 2024. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/appliance-thermometers

- Shelf-stable food safety. Food Safety and Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture. March 24, 2015. Accessed October 26, 2024. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/shelf-stable-food

- Safe food handling. US Food and Drug Administration. November 2, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/buy-store-serve-safe-food/safe-food-handling

- Keep food safe! Food safety basics. Food Safety and Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture. Accessed October 26, 2024. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/steps-keep-food-safe

- Recalls, market withdrawals, & safety alerts. US Food and Drug Administration. November 2, 2022. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts

- Jiang TA. Health benefits of culinary herbs and spices. J AOAC Int. 2019;102(2):395–411. doi:10.5740/jaoacint.18-0418

- Grains. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/grains

- Oldways Whole Grains Council homepage. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://wholegrainscouncil.org

- Whole Grain Cooking Tips. Oldways Whole Grains Council. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://wholegrainscouncil.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/WGC-CookingWholeGrains_0.pdf

- Morrill JS. 6.1: Mouth. In: Science, Physiology, and Nutrition for the Nonscientist. Medicine LibreTexts; October 28, 2021. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nutrition/Science_Physiology_and_Nutrition_for_the_Nonscientist_(Morrill)/06%3A_Digestive_Tract/6.01%3A_Mouth

- Bartoshuk L, Snyder D. Taste and smell. In: Biswas-Diener R, Diener E. (eds). Psychology. Noba textbook series. DEF Publishers. Accessed July 31, 2023. https://nobaproject.com/modules/taste-and-smell

- Breslin PAS. An evolutionary perspective on food and human taste. Curr Biol. 2013;23(9):R409–R418. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.010

- Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;120(11):1011–1020. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192627

- Ramos Da Conceicao Neta E, Johanningsmeier SD, McFeeters RF. The chemistry and physiology of sour taste—a review. J Food Sci. 2007;72(2):R33–38. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00282.x

- Taraszewska A. Risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms related to lifestyle and diet. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2021;72(1):21–28. doi:10.32394/rpzh.2021.0145

- Taruno A, Gordon MD. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of salt taste. Annu Rev Physiol. 2023;85:25–45. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-031522-075853

- How much sodium should I eat per day? American Heart Association. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/sodium/how-much-sodium-should-i-eat-per-day

- Wooding SP, Ramirez VA, Behrens M. Bitter taste receptors: genes, evolution and health. Evol Med Public Health. 2021;9(1):431–447. doi:10.1093/emph/eoab031

- Hartley IE, Liem DG, Keast R. Umami as an ‘alimentary’ taste. A new perspective on taste classification. Nutrients. 2019;11(1):182. doi:10.3390/nu11010182

- Brown AC. Understanding Food: Principles and Preparation. 6th ed. Cengage Learning; 2015.

- Molt M. Food for Fifty. 14th ed. Pearson; 2017.

- Labensky SR, Hause AM, Martel P. On Cooking: A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals. 6th ed. Pearson; 2019.

- Raber M, Chandra J, Upadhyaya M, et al. An evidence-based conceptual framework of healthy cooking. Prev Med Rep. 2016;4:23–28. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.05.004

- Delwiche J. The impact of perceptual interactions on perceived flavor. Food Qual Prefer. 2004;15(2):137–146. doi:10.1016/S0950-3293(03)00041-7

- Small DM, Prescott J. Odor/taste integration and the perception of flavor. Exp Brain Res. 2005;166(3):345–357. doi:10.1007/s00221-005-2376-9

- Guichard E. Interactions between flavor compounds and food ingredients and their influence on flavor perception. Food Rev Intl. 2002;18(1):49–70. doi:10.1081/FRI-120003417

- Spence C, Levitan CA, Shankar MU, Zampini M. Does food color influence taste and flavor perception in humans? Chemosens Percept. 2010;3(1):68–84. doi:10.1007/s12078-010-9067-z

- Lee SK, Kader AA. Preharvest and postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharvest Bio Tech. 2000;20(3):207–220. doi:10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00133-2

- Barrett, DM. Maximizing the nutritional value of fruits and vegetables: review of literature on nutritional value of produce compares fresh, frozen, and canned products and indicates areas for further research. UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences; 2007;61. Accessed October 27, 2024. https://postharvest.ucdavis.edu/publication/maximizing-nutritional-value-fruits-vegetables

- Lee S, Choi Y, Jeong HS, Lee J, Sung J. Effect of different cooking methods on the content of vitamins and true retention in selected vegetables. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2017;27(2):333–342. doi:10.1007/s10068-017-0281-1

- Coe S, Spiro A. Cooking at home to retain nutritional quality and minimize nutrient losses: a focus on vegetables, potatoes and pulses. Nutr Bulletin. 2022;47(4):538–562. doi:10.1111/nbu.12584

- Food loss and waste. US Food and Drug Administration. February 14, 2023. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/consumers/food-loss-and-waste

- Food product dating. Food Safety and Inspection Service, US Department of Agriculture. October 2, 2019. Accessed October 26, 2024. http://www.fsis.usda.gov/food-safety/safe-food-handling-and-preparation/food-safety-basics/food-product-dating

- Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Food waste. The Nutrition Source. April 26, 2017. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/sustainability/food-waste

- Preventing wasted food at home. US Environmental Protection Agency. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 26, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/recycle/preventing-wasted-food-home

Fats found in animal-based foods such as beef, pork, poultry, full-fat dairy products, eggs, and tropical oils. Because they are typically solid at room temperature, they are sometimes called “solid fats.” Source: American Heart Association

Caused by food contaminated with pathogenic microorganisms or toxic substances. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

To reduce or eliminate pathogenic agents (such as bacteria) on the surfaces of something: to make something sanitary (as by cleaning or disinfecting). Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

The inadvertent transfer of bacteria or other contaminants from 1 surface, substance, etc., to another, especially because of unsanitary handling procedures. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Foods likely to spoil, decay, or become unsafe to consume if not kept refrigerated at 40 °F or below, or frozen at 0 °F or below. Source: US Department of Agriculture

A closed container in a refrigerator intended to prevent loss of moisture from fresh produce. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Foods that can be safely stored at room temperature or “on the shelf.” Source: US Department of Agriculture

Lipids that are liquid at room temperature. Source: Nutrition Concepts and Controversies, 15th Edition

The edible seeds of various crops (e.g., peas, beans, lentils) of the legume family. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Fermented whole soybeans mixed with a grain such as rice or millet that has a chewy consistency and a yeasty, nutty flavor. Source: On Cooking: A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals, 6th Edition

A form of wheat gluten with a firm, chewy texture and a bland flavor. Source: On Cooking: A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals, 6th Edition

The temperature at which fat begins to break down and smoke. Source: On Cooking: A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals, 6th Edition

Compounds produced by plants that provide health benefits to the body. Also called phytochemicals or antioxidants. Source: US Department of Agriculture’s National Agriculture Library

A type of chemical found in small amounts in plants and certain foods (e.g., fruits, vegetables, nuts, oils, whole grains) that may promote good health. They are being studied in the prevention of cancer, heart disease, and other diseases. Also known as "bioactive compounds." Source: National Cancer Institute

Naturally occurring chemical compounds, known as polyphenols, that are found in clarifying wine and beer and in medicine.

Any of numerous usually colorless, complex, and bitter organic bases (such as caffeine) containing nitrogen and usually oxygen that occur especially in seed plants. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

A type of polyphenol, including carnosic acid, carnosol, and 12-O-methyl carnosic acid. Source: Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry

A type of phytochemical or plant chemical that creates vibrant colors of fruit, vegetables, and flowers that have a variety of health benefits, such as providing antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, and anti-cancer properties and reduce risk of chronic diseases and improve cognitive functioning. Source: PubMed

Beneficial plant compounds with antioxidant properties that may help keep you healthy and protect against various diseases. Source: Healthline

A varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains. Source: Wikipedia

The blend of taste and smell sensations evoked by a substance in the mouth. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Substances that have an odor, scent, or fragrance. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

The mucus-secreting membrane in the upper nasal cavity that contains cells responsible for initiating the sense of smell. Source: Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, 2009

The part of the mouth behind the gums and teeth that is bounded above by the hard and soft palates and below by the tongue and by the mucous membrane connecting it with the inner part of the mandible (lower jaw). Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

An inflammation of the sinus (a cavity in the substance of a bone of the skull that usually communicates with the nostrils and contains air). Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

A mild to severe respiratory illness that is caused by SARS-CoV-2 virus and characterized by fever, cough, loss of taste or smell, and shortness of breath. It may progress to pneumonia and respiratory failure. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

The building blocks of protein. Each has an amine group at 1 end, an acid group at the other, and a distinctive side chain. Source: Nutrition Concepts and Controversies, 15th Edition

Any of the ions (as of sodium or calcium) that in biological fluid regulate or affect most metabolic processes (such as the flow of nutrients into and waste products out of cells). Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Food that’s changed from its natural state (cut, washed, heated, pasteurized, canned, cooked, frozen, dried, dehydrated, mixed, or packaged). It also can include food that has added preservatives, nutrients, flavors, salts, sugars, or fats. Source: WebMD

A unit of measure, especially in cookery, equal to ¹/₆ fluid ounce or ¹/₃ tablespoon (5 milliliters). Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

The taste sensation that is produced by several amino acids and nucleotides (such as glutamate and aspartate) and has a rich or meaty flavor characteristic of cheese, cooked meat, mushrooms, soy, and ripe tomatoes. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

A French term that translates to “everything in place.” Refers to organizing and arranging ingredients before cooking. Source: Food for Fifty, 14th Edition

Organizations (usually nonprofits) that collect donated food and distribute it to people in need via a number of systems, including food pantries. Source: Feeding America