Chapter 1: Understanding Social Influences, Planning Meals, and Shopping Smarter

By Constance Bell, MBA; Stavroula N. Antonopoulos, MS, RDN; Milad Hasankhani; MSc, Aimee Novak, trained chef

Introduction

Sustaining a healthy eating pattern, one of the goals of culinary medicine, requires ongoing access to nourishing food and strategies to obtain it within an individual’s or family’s resources (e.g., financial and time). Food can be obtained at many venues within a community and at different costs. Factors important to this accessibility include the social determinants of health (SDOH), food and nutrition security, food access, location, resources, and seasonality. This chapter examines the factors influencing food acquisition, paying attention to maximizing nutrient-dense food while minimizing the associated costs, including waste of finances, time, and food. In addition, we will look at how food management and access are related to food and nutrition security.

This chapter provides information on how to build a plan for locating and purchasing nutritious food that is responsive to individual and cultural preferences and sensitive to time available and financial resources. An effective plan starts with understanding individual nutrition needs and setting goals, then creating a list of foods that one enjoys based on these goals, needs, and preferences. A well-developed plan can help individuals and families locate and purchase the most nutritious food possible, given the money and time available to spend. The price of food is not necessarily indicative of its nutritional value, and sometimes spending more on a particular food is worthwhile, given the concentration of nutrients the food provides per unit cost.

Eating seasonally and buying locally grown food are helpful because locally grown food is often the most flavorful, the most nutritious, and typically the most economical. It is also helpful to seek out community programs such as community gardens, local food markets, and farms where one can purchase shares and receive regular packages of farm-fresh products. Freezing and canning local food in season are good methods to limit waste and preserve nutritional value in the long term.

Federal programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are designed to supplement the grocery budgets of families from households with low incomes so they can afford the nutritious food essential to health and well-being. Many states offer the “Double Up Food Bucks” program that doubles the value of SNAP benefits at participating produce markets, helping people bring home more fresh fruits and vegetables while supporting local farmers. The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) aims to safeguard the health of women, infants, and children up to age 5 years who reside in households with low incomes. WIC provides support to those who are at risk of poor nutrition by providing nutritious foods to supplement diets, education and information on healthy eating, and referrals to health care.

Whether in the clinic or the community, culinary medicine incorporates culturally responsive and budget-conscious resources for increasing and sustaining an individual’s health and nutrition security.

Understanding Social Influences

Social determinants of health play a significant role in food planning and acquisition. Social determinants of health are defined as the surroundings where populations perform the routine pursuits of life (e.g., birth, day-to-day activities, schooling, employment, exercise, attending church, aging) that affect their well-being, welfare, and overall happiness. Social determinants of health focus on how non-medical factors influence a person’s physical condition. Certain populations may find it difficult to purchase nourishing food, especially households with reduced access to affordable and nutritious foods related to geographical location, or individuals with limited resources, or both.1

A related concept, food equity, is the expansive concept wherein all people should have the ability and opportunity to grow and consume healthful, affordable, and culturally significant foods. In an equitable food system, all community members can grow, procure, barter, trade, sell, dispose of, and understand the sources of food in a manner that prioritizes culture, equitable land access, fair and equitable prices and wages, human health, and ecological sustainability. Ecological sustainability is the concept that supports people living with respect for the Earth’s environment and their intent to create minimal impact on it. Food equity also requires that food systems be controlled by the wishes of the majority of people and that community stakeholders determine the policies that influence their food system.

Food equity is associated with food access, which goes hand in hand with food and nutrition security. For instance, low food and nutrition security indicates food inequity, which can be influenced by the SDOH, such as the challenge of long distances to a store when one has limited access to or no transportation. With these factors at play, it is more likely that food and nutrition security may be low, perpetuating food inequity. See chapter 11 for more information about the SDOH, food security, and health equity.

Effective food management and access to nutritious food are important determinants of nourishing and balanced eating patterns. This chapter examines the factors influencing food acquisition (e.g., SDOH, location, resources, seasonality)—with attention to maximizing nutrient-dense food while minimizing the associated costs, including waste of finances, time, and food. In addition, we will look at how food management and access are related to food and nutrition security.

Food security is having reliable access to enough affordable, nutritious food. Nutrition security is the means to consistent access, availability, and affordability of foods and beverages that promote well-being and prevent (and, if needed, treat) disease, particularly among racial/ethnic minority populations, historically lower-income populations, and rural and remote populations. Nutrition security builds on and complements efforts to address food security among all people but recognizes that not every person maintains an active, healthy lifestyle. Nutrition security also emphasizes the importance of using equity-sensitive approaches for populations that often are managing the co-existence of food insecurity and nutrition-related chronic diseases or illnesses that are influenced by dietary practices and nutrition. Enabling consumers to use food labels in meal planning to meet caloric and nutrient needs is also an important aspect of nutrition security.2

In the next section, meal planning is discussed, which aims to support the most nutritious, economical, and least wasteful methods of approaching shopping and food procurement. Also, we acknowledge the influences of food security and nutrition security as major factors in determining the level of quantity, quality, and nutritive value of that food.

Meal Planning

Nutrition and healthcare professionals often advise their patients and clients to optimize their eating habits to better manage their health. One way to promote healthier eating patterns is through a structured meal plan. Studies have shown that meal planning can lead to more nutritious food choices as well as improved dietary intake.1 Meal planning can save time, cut food costs, help manage weight, and reduce the stress of last-minute meal preparation. Meal planning can also aid in preventing unnecessary purchases, impulse buying, and overspending.

A meal planning template can be used to achieve nutritional goals and to reduce food waste.3-5 The elements of a meal plan include defined goals (e.g., improved health, improved athletic performance, specific dietary needs), caloric and nutritional needs, meal frequency, food choices, portion sizes, and preparation. Plan and create a grocery list based on the meal plan and recipes.3 Try new recipes to incorporate a variety of nutrient-dense foods.

Meal plan templates can vary (see the “Helpful MyPlate Tools for Meal Planning” text box), but it is common to see a weekly meal plan that outlines the foods and beverages that will be eaten each day. A meal planning template typically uses a calendar or list structure. The goal is to have an idea and plan for meals and snacks, but flexibility is key. Patients or clients should be encouraged to start small, gradually changing their eating habits over time. Suggest that patients or clients start by planning just a few meals each week and gradually increase that, sourcing additional resources and support as needed.

Helpful MyPlate Tools for Meal Planning

Note that registered dietitian nutritionists are qualified to create meal plans because they have extensive education and training in nutritional sciences, dietetics, medical history, and dietary practices. Laypersons can create meal plans for general well-being but may not have the robust education for more health- and condition-specific meal plans. Different regions of the United States may set other standards for dietitians, including education, practical experience, and qualifying exams.

Honoring Traditional, Cultural, and Ethnic Foods

NOTE: To better tailor your meal planning tips to your patients or clients, see chapter 12 for information on traditional, cultural, and ethnic food considerations. Learn more about eating patterns from around the world at Diets Around the World.

Nutritious Meal Planning

In the interactive activities throughout this chapter, select the > to read additional information and try the self-quizzes to test your knowledge:

Shopping Smarter

Now that we are acquainted with the process of meal planning, let’s be strategic in the acquisition of nutritious food. Next, we will look at where people typically get food and identifying features of each place.

Where Can I Access Food?

Food may be acquired from a variety of places, including the following:

- Grocery stores primarily sell food and beverages along with limited household products.

- Online shopping can be retailer-specific or accessed by online platforms and/or applications (apps). Local stores may offer delivery or curbside pickup of food ordered online. Online platforms and apps, such as Amazon Fresh and Instacart, serve as third-party intermediates, fulfilling orders for retailers and delivering purchases directly to customers. Reducing or eliminating the time spent on shopping is part of the appeal of online shopping; however, the tradeoff can be a lack of choice and an inability to self-select quality food.

- Corner stores are like grocery or convenience stores except they are smaller and may also carry tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, prepared foods, and a limited produce selection.

- Convenience stores are convenient to customers, typically in closer proximity, and open longer hours than food stores—even 24 hours. They carry a limited selection of necessities, such as packaged foods and drugstore items.

- Farmers markets provide consumers with a seasonal array of agricultural products for direct purchase. Offerings may include fruits, vegetables, milk, cheese, and honey, among other products. Farmers markets eliminate intermediaries between farmers and consumers, thus supplying some of the freshest food items.6

- Food banks provide donated food items at no cost to those in need. Food items typically consist of canned and packaged goods and, potentially, local produce, eggs, and other items from local farmers or organizations. Food banks can offer access to fresh, nutritious foods for those who might not otherwise have the resources to acquire them.7 For further information on food banks, watch this Food Banks video from Feeding America.

- Community-supported agriculture (CSA) is an initiative that enables local buyers to prepay a sum to a farm, which then entitles them to receive recurring packages of the farm’s fresh products, including fruits, vegetables, eggs, meat, poultry, and more.8,9

- Community gardens are where members of a community collaborate within a designated area to grow and maintain fresh fruits, vegetables, herbs, and flowers. These gardens provide fresh, locally cultivated produce, as well as opportunities for physical activity, healthier eating, community cohesiveness, education, and reduced family food budgets.8,9

- Mobile markets bring more affordable, fresh food options to different neighborhoods without having a permanent infrastructure.7,10,11

Additional Resources in Your Community

Some colleges and universities may have student and community support resources such as food pantries. For example, the University of Arizona has a Student Basic Needs Coalition that sponsors a Campus Pantry to provide free food for students, faculty, staff, and the university community. Look in your community for similar opportunities.

Find local food by visiting these websites:

- Local food directory listings

- Farmers markets

- Community Supported Agriculture (CSA)

- Community gardens

- Food pantries/banks

Tips for Healthier Shopping

- Focus on purchasing fruits, vegetables (fresh or frozen), whole grains, plant-based proteins (e.g., beans), lean meats (e.g., chicken breast), and low-fat dairy products.5,10

- Select minimally processed foods over those with added sugars, sodium, saturated fats, and trans fats. Look for food options with reduced or no added sugar or sodium.3,7

- Read nutrition labels, being mindful of the serving size, calories per serving, and nutrition content.3,7 See the section Deciphering Food Labels for Nutrition for nutrition label information.

- Shop the perimeter of the store, where fresh produce, meat, and poultry can often be found.

- When shopping online, envision the store’s perimeter and choose items typically found there.

Access to Affordable, Nutritious Food

- Learn more about access to affordable, nutritious food

- When budgets are strained, these resources may be helpful:

- Eat Right When Money’s Tight

- Smart Shopping and Eating Healthy on a Budget

- Many states offer the “Double Up Food Bucks” program that doubles the value of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits at participating markets, helping people bring home more nutritious fruits and vegetables while supporting local farmers. Learn more about Double Up Food Bucks.

More Affordable, Nutritious Grocery Shopping Tips

Pricing Tips Price per item, per ounce (oz), or per pound (lb)

![A shelf label at a grocery store showing product name (ReaLime lime juice), amount (8 fl oz), item price ($1.99), and unit price ($31.84 per gallon).]](https://opentextbooks.library.arizona.edu/app/uploads/sites/11/2024/10/Figure-1.4_unit-price-tag-225x300.jpg)

- Most stores have a shelf label that displays the price of the item and the cost per unit, as seen in Figure 1.4.

- Items may be priced by the item or by the unit (e.g., 1 muffin), the ounce (oz), or by the pound (lb.). Vegetables, fruits, fresh meats, and bulk items are usually charged by the unit (pounds or ounces). Something premade or already packaged will typically be priced by the package.

- Standardize the price per unit to effectively comparison shop. For example, an item that is $0.23/oz and another item that is $3.68/lb. are the same price ($0.23 × 16 oz = $3.68 for 16 oz, or 1 lb.).

- In Fig. 1.4, calculate the price per oz ($1.99/12 oz = $.25). To compute price/gal, multiply the price/oz times oz/gal (128 oz/gal) ($.25 x 128 = $31.84 cost/gal).

Try Eating Seasonally and Locally

Consuming locally grown food is beneficial because of its freshness and nutritional density. Fruits and vegetables harvested at their peak ripeness and consumed closest to that time retain most of their moisture, nutrients, and freshness. When produce is picked at its peak, it contains higher concentrations of critical nutrients such as potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and vitamins C and A.13,15 When foods are separated from their source of nutrients, they begin to lose moisture and quality, which can lead to microbial spoilage. Learn more about Health Benefits of Eating Locally and see the section Distance Traveled for more details.

Why Eat Seasonally?

Seasonal produce involves selecting foods that are freshly harvested and available during specific times of the year. Planning your meals based on the season’s offerings has numerous advantages, including:

- Enhanced flavor and freshness: When harvested at its peak, seasonal food is typically at its ideal texture and taste. In contrast, out-of-season food may have been transported long distances or stored for extended periods, adversely affecting its freshness and taste.

- Nutritional value: Fresh seasonal food contains optimal nutrients because it is customarily harvested closer to consumption. However, frozen and canned produce also have significant nutrients because they are picked at peak ripeness, processed almost immediately, and usually onsite. Because the quality of the vitamins and minerals in fresh fruits and vegetables tends to diminish over time, seasonal produce can be more nutritious than food not in season.

- Cost savings: Seasonal food is, in many cases, often less expensive than out-of-season food because it spends less time in transit or storage for long periods. Additionally, the price can be more competitive when farmers or grocery stores have large quantities of fresh food items available. Frozen and canned produce can be the exception to that, because the shelf life of both is longer than that of fresh produce, it still retains nutrients and can be affordable.

- Environmental benefits: Eating local and seasonal food helps reduce the carbon footprint of our food system by selecting items grown nearby, thus reducing the need for long-distance transportation. Transporting food over long distances demands a lot of fuel energy and produces greenhouse gas emissions.

- Supports local agriculture: Purchasing locally grown food supports small businesses and helps keep agricultural land in use. This, in turn, strengthens local food systems, the local economy, and helps build a sense of community.

Videos With Tips About Fresh Produce

- Farmers Markets—Fresh, Nutritious, Local (US Department of Agriculture/Nutrition.gov)

- Community Gardens—10 Steps to Successful Community Gardens (University of Illinois Extension)

- What Is Community Supported Agriculture (CSA)? (OrganicNation)

Here are tips to help you eat seasonally:

- Know what’s in season: Determine what foods are available in your area and plan your meals accordingly. You can find this information by visiting local farmers markets, checking seasonal produce guides, or talking to local farmers. Also, check your local grocery ads.

- Shop at farmers markets: Farmers markets are an excellent place to buy seasonal produce directly from local farmers. You’ll find a variety of fresh fruits and vegetables that are in season, and you’ll support local agriculture in the process.

- Join a CSA program: A CSA program is a subscription service that curates fresh seasonal produce from local farms. As a CSA member, you will receive a regular supply of fresh, seasonal produce from local farms delivered to your home or made available for pickup at a centralized location.

- Preserve seasonal foods: If you have an abundance of seasonal produce, consider preserving it for later use. You can freeze, can, or dehydrate fruits and vegetables to enjoy when they’re out of season. For more information on preserving fruits and vegetables, see chapter 2.

- Get creative with recipes: Try new recipes that use seasonal ingredients. Be bold and select one or 2 new produce items to cook with each week. Experiment with different ways of cooking and preparing seasonal produce to discover new flavors and textures.

- Be flexible: Be adaptable when eating food in season. Adjust your menu to what is available. If shopping locally for your produce is an option, be ready to swap out an ingredient if the market does not have what you’re looking for. Ask the farmers or vendors for suitable substitutes and advice on preparing and cooking the items. By doing so, you’ll be able to enjoy seasonal produce to the fullest while supporting your local community and the environment.

Distance Traveled

The average amount of time it takes for produce to reach its final destination can vary depending on several factors, including the type of produce, the distance it needs to travel, and the transportation method used.13 Generally, domestic produce may take anywhere from 1 to 7 days to reach its destination, and international produce can take much longer.13 For example, produce from Mexico or South America to the US Midwest may take anywhere from 5 to 14 days, depending on the transportation method used and any customs or inspection procedures required.

Transportation time is just one factor that can affect the quality and freshness of produce.13 Other factors—such as storage conditions, handling practices, and the age of the produce at the time of harvest—can also affect the quality and nutritional value of the final product.13

By the time produce reaches the table, nutrient degradation may occur, which refers to the process by which essential nutrients in food, such as vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) deteriorate or break down over time, resulting in a reduction of nutritional value. Nutrient degradation can occur due to various factors, including exposure to air, light, heat, moisture, cooking, and enzymatic reactions. As nutrients degrade, their bioavailability and effectiveness in providing essential components for the body’s functioning may diminish. It is important to store and handle food properly to minimize nutrient degradation and ensure that the nutritional value of the food is preserved for consumption. When nutrient degradation occurs, it is primarily driven by a reduction in water-soluble vitamins, including B vitamins and vitamin C. Once harvested, produce undergoes higher rates of respiration and moisture loss, further contributing to nutrient degradation.

Deciphering Food Labels for Nutrition

When navigating the food choices wherever one shops, there is an objective measure of a product’s nutritional value: the food label. Understanding food labels is vital. This section provides insight into these labels to enable the consumer to make informed, nutritionally sound decisions that align with nutrition goals. Whether one is a seasoned shopper or just beginning to be mindful of food choices, this section demystifies food labeling and nutrition facts, empowering health-conscious food selection.

Food Labeling

Understanding Food Labeling and Related Regulations

Food labeling is a crucial aspect of food production and marketing, providing health professionals and consumers with essential information about the food they consume. It is regulated by various authorities worldwide, with the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) being the primary regulatory body in the United States. Understanding the ingredient list on food labels can be challenging, but it is a vital skill for health-conscious consumers and those advising them.14

Ingredients, Additives, and Colors

Food labeling involves providing detailed information about a food product on its packaging. This information typically includes the product’s name, ingredients, nutritional information, common allergens, manufacturer details, whether a product is organic or contains a genetically modified organism, and any relevant health claims. The ingredient label is mandated to list all components of the food product, including primary ingredients, fortifying nutrients, flavorings, sweeteners, and additives.

Certain ingredients may appear in various forms or derivations but have similar nutritional effects. For instance, sugars may be listed as corn syrup, agave nectar, or be listed by their chemical terminology (e.g., fructose). Manufacturers may use this nomenclature for marketing purposes. Regulatory standards mandate truthful disclosure of all ingredients.14,15

On food labels, ingredients are listed in descending order by weight. This means that the ingredient that weighs most is listed first, and the ingredient that weighs the least is listed last. If sugar or fat is listed as one of the first few ingredients, it means that the product is high in these items and so less likely to have high nutritional value. Conversely, if whole grains or other nutrient-dense ingredients are listed first, the product is likely to be a more nutritious choice.14

Exemptions from Nutrition Labeling Requirements

Although most food products are required to have nutrition labels, certain businesses and specific types of food are exempt from this requirement. These exemptions are based on various factors, such as the size of the business and the type of food product. Raw fruits, vegetables, fish, and single-ingredient meats are exempt from labeling requirements. Additionally, foods served or sold in bulk or prepared on-site by delis and bakeries are not required to have information labels.

Even if a food product is exempt from nutrition labeling requirements, it is still subject to other food labeling regulations, wherein the product’s name and ingredients must still be accurately represented on the label.14,15

Allergen Information

Allergen information is mandated to be clearly and obviously placed beneath the ingredient label. In the United States, food labels are required to identify the top 9 major allergens: milk, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soybeans, and sesame. Potential cross-contact with allergens must also be disclosed. Food allergens can be listed on labels under different names or aliases. It’s important to recognize these alternate names to avoid accidental exposure to allergens. Table 1.1 lists some common aliases for various food allergens.16,17

Table 1.1. Food Label Allergens

| Allergen | Aliases16,17 |

|---|---|

| Eggs | Albumin, globulin, lecithin, livetin, lysozyme, ovalbumin, ovoglobulin, ovomucin, ovomucoid, ovotransferrin, ovovitellin, Simplesse |

| Fish | Anchovy, bass, catfish, cod, flounder, grouper, haddock, hake, halibut, mahi-mahi, perch, pike, pollock, salmon, sole, snapper, swordfish, tilapia, trout, tuna |

| Peanuts | Arachis oil, beer nuts, ground nuts, mandelonas, nut meat, nut pieces, peanut butter, peanut flour |

| Shellfish | Abalone, clams, crab, crawfish, krill, lobster, mussels, oysters, prawns, scallops, shrimp, squid |

| Soy | Edamame, miso, natto, shoyu, soy albumin, soy concentrate, soy fiber, soy formula, soy grits, soy milk, soy nuts, soy protein, soy sauce, soy sprouts, tamari, tempeh, textured vegetable protein, tofu |

| Tree nuts | Almonds, Brazil nuts, cashews, chestnuts, filberts/hazelnuts, hickory nuts, macadamia nuts, marzipan/almond paste, nougat, pecans, pine nuts/pignolias, pistachios, walnuts |

| Wheat | Bran, bread crumbs, bulgur, cereal extract, club wheat, couscous, cracker meal, durum, einkorn, emmer, farina, flour (all-purpose, bread, cake, durum, enriched, graham, high-gluten, high-protein, instant, pastry, self-rising, soft wheat, steel ground, stone ground, whole wheat), gluten, hydrolyzed wheat protein, Kamut, matzoh, matzoh meal (also spelled matzo, matzah, or matza), pasta, seitan, semolina, spelt, sprouted wheat, triticale, vital wheat gluten, wheat (berries, bran, durum, germ, gluten, grass, malt, sprouts, starch), wheat bran hydrolysate, wheat germ oil, wheat grass, wheat protein isolate, whole wheat berries |

| Sesame | Benne, benne seed, benniseed, gingelly, gingelly oil, halvah, sesame flour, sesame oil, sesame paste, sesame salt (gomashio), sesame seed, sesamol, Sesamum indicum, simsim, tahini, tehina, til |

The Nutrition Facts Label and Nutritional Density

The Nutrition Facts Label

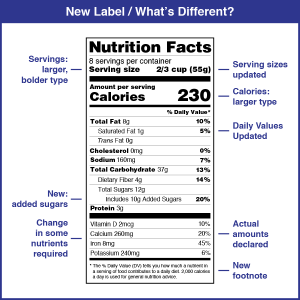

In recent years, the Nutrition Facts label on food packaging has undergone substantial changes to make it more informative and easier to understand. Some key changes include larger font size for calories, serving sizes updated to reflect the amounts people typically consume, and the addition of the term “added sugars” to help consumers distinguish between added sugars and naturally occurring sugars.18,19

Serving Size, Servings Per Container, and Portion Size

In the United States, a serving size is a reference amount of food, as defined by the FDA, that helps consumers understand the nutritional content of a certain quantity of food. A serving is a measured portion of food or drink.

The number of servings per package must be based on the serving size of the product. For example, if the serving size of quinoa is 1 cup and a package contains 4 cups, then the number of servings per container is 4.20 In contrast, portion size is the amount of food that a typical consumer would choose to eat for a meal or a snack, which can be larger or smaller than the FDA standard serving sizes.20 For example, if you chose to eat 2 cups of quinoa, your portion size would be 2 cups even though the indicated serving size is 1 cup.20

Understanding these terms can help you make more nutritious food choices. For instance, you might think a small package of quinoa is 1 serving, but if the label says it contains 4 servings, that equals 4 times the calories, protein, fiber, and other nutrients listed on the label.

What Is Percent Daily Value and How Is It Calculated?

The term Percent Daily Value (%DV) on food labels is a guide to the nutrients in 1 serving of food. The %DV is based on the recommended daily intake of a nutrient, which is the amount of a nutrient the average person needs each day.21 This information can help you determine if a serving of food is high or low in a particular nutrient.21

The %DV is calculated based on a 2,000-calorie/day eating pattern for adults and children aged 4 years or older; however, your needs may be more or less depending on your age, sex, weight, and physical activity level.21

Here is how it works:

- Identify the nutrient: The nutrient content of the food is determined through laboratory analysis or by using a database of nutrient composition values for foods.21

- Determine the %DV: The %DV is calculated by dividing the amount of a nutrient in a serving of the food by the recommended daily intake for that nutrient, then multiplying by 100.22

For example, if a food has 3 g of fiber per serving and the daily recommended intake for fiber is 25 g, the %DV for fiber would be (3 ÷ 25) × 100 = 12%. So, one serving of this food provides 12% of the daily recommended intake of fiber.22

Table 1.2 lists the reference values that are used to calculate the %DV on the Nutrition Facts label.21 Note, however, that the recommended intake for a nutrient can vary for each person. Generally, a nutrient amount per serving that is 5% DV or less is deemed low, and a nutrient amount per serving that is 20% DV or more is deemed high.

Table 1.2. The Percent Daily Value Calculation on the Nutrition Facts Label21

| Nutrient | Current Daily Value | Nutrient | Current Daily Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Added sugars | 50 g | Phosphorus | 1,250 mg |

| Biotin | 30 mcg | Potassium | 4,700 mg |

| Calcium | 1,300 mg | Protein | 50 g |

| Chloride | 2,300 mg | Riboflavin | 1.3 mg |

| Choline | 550 mg | Saturated fat | 20 g |

| Cholesterol | 300 mg | Selenium | 55 mcg |

| Chromium | 35 mcg | Sodium | 2,300 mg |

| Copper | 0.9 mg | Thiamin | 1.2 mg |

| Dietary fiber | 28 g | Total carbohydrate | 275 g |

| Fat | 78 g | Vitamin A | 900 mcg RAE |

| Folate/folic acid | 400 mcg DFE | Vitamin B6 | 1.7 mg |

| Iodine | 150 mcg | Vitamin B12 | 2.4 mcg |

| Iron | 18 mg | Vitamin C | 90 mg |

| Magnesium | 420 mg | Vitamin D | 20 mcg |

| Manganese | 2.3 mg | Vitamin E | 15 mg α-tocopherol |

| Molybdenum | 45 mcg | Vitamin K | 120 mcg |

| Niacin | 16 mg NE | Zinc | 11 mg |

| Pantothenic acid | 5 mg | ||

| Abbreviations: DFE = dietary folate equivalents; g = gram; IU = international unit; mcg = microgram; mg = milligram, NE = niacin equivalents; RAE = retinol activity equivalents. | |||

The %DV helps the consumer understand the nutrient content of a serving of food in the context of a total daily diet.20 Knowing the %DV can help when making dietary choices that can lower the risk of chronic diseases such as heart disease, cancer, or osteoporosis.20

Note, however, that the %DV does not indicate how much of a nutrient is in a serving of food. It indicates the percentage of the recommended daily intake contained in that serving of food.20 If a food has a %DV of 20% for calcium, it does not mean you are getting 20% of your daily calcium from that food. It means you’re getting 20% of the recommended daily intake for calcium.22

Using the Nutrition Facts Label and MyPlate

The FDA’s MyPlate is a visual guide that helps you create balanced meals based on the 5 food groups.22 The Nutrition Facts label and MyPlate can be used together to make more nutritious food choices that align with your nutritional needs and goals.22

Key Takeaways

- Make a meal plan and create a grocery list that includes an inventory of what you have to help plan nutritious and cost-effective meals. Use a meal planning template to balance meals, maximize nutritional choices, stay within budget, avoid over- or impulse spending, and minimize food waste.

- Shopping can be at grocery stores, online, corner or convenience stores, farmers markets, food pantries/banks, CSAs, and community gardens.

- Social determinants of health have an influence on food equity, food and nutrition security, as well as food access. Thus, the ways of acquiring food depend on SDOH.

- Shop for items on sale, compare pricing using units of weight and cost, and choose store or generic brands to save money. Consider buying in bulk.

- Explore seasonal and local foods because they can be fresher and more flavorful. Produce harvested nearer to you has optimal nutrient composition, but produce can be sourced domestically and internationally, depending on the season and availability. Also consider the value of frozen or canned produce, which is often picked at its peak and packaged close to where it is harvested.

- Understand food labeling on the package and its information, including ingredients, nutritional content, and potential allergens. The Nutrition Facts label provides information about the nutritional content of food, including serving sizes, %DV, and other key nutrients. Refer to MyPlate for balanced nutrition guidance.

References

- Lindstrom KN, Tucker JA, McVay M. Nudges and choice architecture to promote healthy food purchases in adults: a systematized review. Psychol Addict Behav. 2023;37(1):87–103. doi:10.1037/adb0000892

- Food and nutrition security. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/priorities/food-and-nutrition-security

- Make a plan. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/healthy-eating-budget/make-plan

- More key topics. US Department of Agriculture. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/more-key-topics

- Gordon B. 3 Strategies for successful meal planning. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. July 18, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.eatright.org/food/planning/smart-shopping/3-strategies-for-successful-meal-planning

- Farmers markets increase access to fresh, nutritious food. Farmers Market Coalition. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://farmersmarketcoalition.org/education/increase-access-to-fresh-nutritious-food/

- Madlala SS, Hill J, Kunneke E, Lopes T, Faber M. Adult food choices in association with the local retail food environment and food access in resource-poor communities: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1083. doi:10.1186/s12889-023-15996-y

- Howarth M, Brettle A, Hardman M, Maden M. What is the evidence for the impact of gardens and gardening on health and well-being: a scoping review and evidence-based logic model to guide healthcare strategy decision making on the use of gardening approaches as a social prescription. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e036923. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-036923

- Nogeire-McRae T, Ryan EP, Jablonski BBR, et al. The role of urban agriculture in a secure, healthy, and sustainable food system. BioScience. 2018;68(10):748–759. doi:10.1093/biosci/biy071

- Wei Y, Shannon J, Lee JS. Impact of grocery store proximity on store preference among Atlanta SNAP-Ed participants. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2022;54(3):263–268. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2021.01.004

- Lucan SC, Maroko A, Sanon O, Frias R, Schechter CB. Urban farmers’ markets: accessibility, offerings, and produce variety, quality, and price compared to nearby stores. Appetite. 2015;90:23–30. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2015.02.034

- Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1181–1188. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.29300

- Barrett DM. Maximizing the nutritional value of fruits & vegetables: review of literature on nutritional value of produce compares fresh, frozen, and canned products and indicates areas for further research. UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences; 2007;61(4). Accessed October 27, 2024. https://postharvest.ucdavis.edu/publication/maximizing-nutritional-value-fruits-vegetables

- US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. Guidance for industry: food labeling guide. DHHS; September 23, 2022. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-food-labeling-guide

- Gager E. Finding the hidden sugar in the foods you eat. John Hopkins Medicine. August 8, 2021. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/finding-the-hidden-sugar-in-the-foods-you-eat

- Allergen control resources. California Department of Public Health, Food and Drug Branch. May 28, 2019. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CEH/DFDCS/Pages/FDBPrograms/FoodSafetyProgram/AllergenControlResources.aspx

- The top 8 food allergens and their common aliases. California Department of Public Health, Food and Drug Branch. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CEH/DFDCS/CDPH%20Document%20Library/FDB/FoodSafetyProgram/AllergenControlResources/Allergens.pdf

- Changes to the Nutrition Facts label. US Food and Drug Administration. April 13, 2023. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/changes-nutrition-facts-label

- Added sugars on the new Nutrition Facts label. US Food and Drug Administration; February 25, 2022. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/added-sugars-new-nutrition-facts-label

- Guidance for industry: food labeling: serving sizes of foods that can reasonably be consumed at one eating occasion; dual-column labeling; updating, modifying, and establishing certain reference amounts customarily consumed; serving size for breath mints. Docket no. FDA-2004-N-0258. Human Foods Program. US Food and Drug Administration; September 21, 2022. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/guidance-industry-food-labeling-serving-sizes-foods-can-reasonably-be-consumed-one-eating-occasion

- The lows and highs of percent daily value on the new Nutrition Facts label. US Food and Drug Administration; February 25, 2022. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/lows-and-highs-percent-daily-value-new-nutrition-facts-label

- Using the Nutrition Facts label and MyPlate to make healthier choices. US Food and Drug Administration; February 25, 2022. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/using-nutrition-facts-label-and-myplate-make-healthier-choices

- Zimmerman M, Snow B. 2.7: Understanding Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI). In: An Introduction to Nutrition. Medicine Libre Texts; 2016. Accessed October 22, 2024. https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nutrition/An_Introduction_to_Nutrition_(Zimmerman)/02%3A_Achieving_a_Healthy_Diet/2.07%3A_Understanding_Dietary_Reference_Intakes_(DRI)

The conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. Source: World Health Organization

Collaborative projects on shared open spaces where participants share in the maintenance and products of the garden. Source: US Department of Agriculture

A government program that provides food benefits to low-income families to supplement their grocery budget so they can afford nutritious food. Source: SNAP

A program that provides federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age 5 who are found to be at nutritional risk. Source: US Department of Agriculture

The concept that people should have equal access to and the ability to grow and consume nutritious, affordable, and culturally significant foods. Source: University at Buffalo Community of Excellence in Global Health Equity

The state of having reliable access to sufficient quantities of affordable, nutritious food. Source: Oxford English Dictionary

Having consistent and equitable access to healthy, safe, affordable foods essential to optimal health and well-being. Source: US Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture

Developed and published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, this contemporary nutrition guide aligns with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Source: US Department of Agriculture

Stores or marketplaces where groceries (food, beverages, and common household goods) are sold. Source: Allrecipes

A form of electronic commerce that allows consumers to directly buy goods or services from a seller over the Internet. Source: Wikipedia

Small stores, usually on the corner of a street, that sell mainly food and household goods. Source: Collins Dictionary

Small stores that sell mainly food and are usually open until late at night. Source: Collins Dictionary

Typically temporary retail establishments held outdoors, where farmers sell their produce at a specified place and time directly to customers. Source: National Center for Appropriate Technology

Organizations (usually nonprofits) that collect donated food and distribute it to people in need via a number of systems, including food pantries. Source: Feeding America

A system in which a farm is supported by local consumers who purchase prepaid shares in the farm's output, which they receive periodically throughout the growing season. Source: Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

Markets that travel to customers, such as a refrigerated van that brings fresh produce to a neighborhood to sell to its residents. Source: Health Care Without Harm

Fats found in animal-based foods such as beef, pork, poultry, full-fat dairy products, eggs, and tropical oils. Because they are typically solid at room temperature, they are sometimes called “solid fats.” Source: American Heart Association

The unit used to measure the energy in foods is a kilocalorie; it is the amount of heat energy necessary to raise the temperature of a kilogram (a liter) of water 1 degree Celsius. Source: Nutrition Concepts and Controversies, 15th Edition

The proportion of the nutrient that is digested, absorbed, and metabolized through normal pathways. Source: The Journal of Nutrition

Fermented whole soybeans mixed with a grain such as rice or millet that has a chewy consistency and a yeasty, nutty flavor. Source: On Cooking: A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals, 6th Edition

A form of wheat gluten with a firm, chewy texture and a bland flavor. Source: On Cooking: A Textbook of Culinary Fundamentals, 6th Edition