Part 2: Dances of Western Europe and its Colonies

3 Dances of Great Britain and Ireland

1. Geography

The British Isles are the archipelago of islands on the western edge of Europe.[1] Great Britain refers to the largest island, which is made up of the countries of England, Scotland (Alba) and Wales (Cymru). Scotland is in the north of the isle of Britain, England in the south and Wales in the west. The large Island to the west of that is Ireland, which today consists of two distinct political units: The Republic of Ireland (Éire) and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom, a political union between the governments of N. Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England. The Isle of Man is a self-governing part of the British Isles. Another important cultural area is Cornwall, which is the peninsula at the far SW of England. Cornwall has a distinct cultural identity from the rest of England, associating itself more closely with Wales and Brittany due to its Celtic roots.

2. A Little Bit of History

British and Irish history is well documented elsewhere and is probably familiar to many of you, so I am not going to spend too much time on it.

After the last Ice Age, the British Isles were populated by two distinct waves of people who we identify as Celts. The first group spoke a P-Celtic language. That means that words that in Proto-Indo-European started with a kw sound, came to be pronounce with a p. For example, the word meaning four in Welsh is pedwar (compare to English quarter). The other group, which came later spoke a language where the same words came to be pronounced with a simple k sound (so Scottish Gaelic, four is ceithir). This latter group were known as the Q-Celts. P-Celtic peoples settled throughout the islands, well up into Scotland and throughout Wales and England. The Welsh and Cornish traditionally spoke languages (Cymraeg and Kernowyon) that are descended from the P-Celtic language. The Q-Celts came to occupy Ireland, and Northern Scotland. The people who speak Irish Gaelic (Gaeilge), Manx Gaelic (Gaelg) and Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) are descendants of the Q-Celts.

England and Wales were occupied by the Romans in ancient times, but the Romans never successfully occupied Scotland or Ireland. When the Roman empire collapsed, England and southern Scotland were occupied by Germanic speaking peoples (the Anglo-Saxons). Their language came to be realized by two modern languages: Scots, spoken in the lowlands of Scotland, Northern England, and later after immigration in the 17th century, in Ulster and English, the world language we are all familiar with.

Scotland, Ireland, and Northern England were frequent targets of Viking incursions during the dark ages. Northern Scotland and the Hebrides Islands were part of the Kingdom of Norway for a long time. This came to shape the language and culture of these regions.

In 1066, William the Conqueror, invaded England and brought with him a Norman French aristocracy. The Anglo-Normans have remained the dominant force in Britain for the past 1000 years. What followed were 800 years of conflict, invasions, rebellions with the other parts of the islands. The last pitched battle on British soil was the battle of Culloden in 1745, which marked the end of the Scottish Jacobite Rebellion.

In the 1920s, after an intense movement for independence the Republic of Ireland separated from the UK. This resulted in the partition of the island into the Republic and Northern Ireland. In recent years there have been very active independence movements in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. In the past 25 years, Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland have all gained their own regional parliaments with devolved governing powers. (See Kearney 2005 for a more in depth and fully sourced history of the British Isles)

3. England and Cornwall

The dance traditions of England and Cornwall can be roughly grouped into three major classes: (1) Morris and related ritual dances, (2) English Country Dancing, and (3) Solo dances usually involving clogging.

3.1. Morris Dancing

Morris dancing seems to be an ancient dance form, perhaps dating back to the early Indo-Europeans[2]. We find very similar dances throughout Europe (see for example the Căluşari of Romania), with very similar costumes, using similar props like sticks, and using movements that are meant to be reminiscent of the movements of horses. They often involve the presence of a special character, called “the fool” in Morris dancing, who acts as the MC for the show and plays and interacts with the dancers. There are good reasons to think that Morris dancing is quite old. Many dances that feel like Shamanistic rituals are still done. Take for example the Abbot Bromley Horn Dance, where the dancers wear deer horns. ¯Historically Morris dancing was only done by Men, but now it is widely done by all genders. The name Morris is thought to related to “Moorish”, referring to the peoples of North Africa.

Morris dancing costumes are typically white shirts and white pants. The dancers have two red sashes crossed over their bodies, and they have shin guards covered in ribbons and bells that jingle as they dance. They are usually equipped with sticks, which they smack against each other as they pass. Handkerchiefs are used in some dances rather than sticks.

Morris dancing is done to reels and jigs and is almost always performed to live music performed by a solo musician or sometimes a duet. The dancers do large hopping and leaping steps forming figures in a set.

In recent years one particular kind of Morris dancing has become very controversial. In some Morris traditions, the dancers wear black face, which is now considered deeply offensive by many. There are many explanations for the black face. Some attribute it to the fact that the dancers were often coal miners, which means their faces were blacked from work rather than as a cosmetic add on. Others attribute to the fact that Morris dancing often has pagan overtones and has been banned at various times, so the dancers blackened their faces as a disguise. But of course, the most obvious explanation is that it is meant to represent the Moors of North Africa, after whom the dance style is named. The blackface tradition dates to the 1400s at least, but it is currently a source of massive debate in England as to whether in contemporary times it is racist or not.

- Morris with sticks[3]: https://youtu.be/V72qxbTu5ao

- Morris with handkerchiefs: https://youtu.be/sArAC2_ow2k

- Morris Dance in blackface: https://youtu.be/fniZzaViEZc [TRIGGER WARNING: this video contains images of dancers in blackface which people may find offensive.]

- Abbot Bromley Horn Dance: https://youtu.be/q5qCfQlipqE

There are many related dance traditions to Morris dancing. The very exciting and complicated rapper dances form complicated patterns jumping over and around metal “rappers” (which may be representative of metal threshing tools). Similarly, there are strong traditions of sword dancing in some areas of England.

- Candyrapper Rapper Side: https://youtu.be/G5EDCfSKU-0

- Candyrapper side, 2nd video: https://youtu.be/8Yrox9H_9qo?si=hHr_42JFF3-UGjRn

- Tower Ravens Side: https://youtu.be/jCzra-LroRE?si=8pW9XcqltYTnqZFR

- Stone Monkey Longsword dancing: https://youtu.be/CIjq3c-wVGg?si=vebq_tFgc7_gx1r0

3.2. English Country Dancing and Playford Dances

The second major type of English folk dance is English Country Dance (ECD). ECD dances are clearly descended from the European court dances of the 15-17th centuries CE.[4] They are typically in reel (2/4), waltz (3/4) and jig (6/8) rhythms. English country dances are most often done in what are called “longwise sets”. This refers to the physical arrangement of the dancers. The dances are done as couples, with the men in a long line on one side facing the women in a long line on the other. The longwise set is subdivided into minor sets of 2 to 3 couples, depending upon the particular dance. Within each minor set there is an “active couple”, usually the couple closest to the music, and an “inactive couple”. The dancers execute several figures that result in the couples having switched position. The dancers then dance the same role (active/inactive) with the next couple they meet in the longwise set. Active couples progress down the set away from the music, inactive couples progress up the set towards the music. Once a couple hits the top or bottom of the long set, they sit out a turn and then return to the dance in the other role.

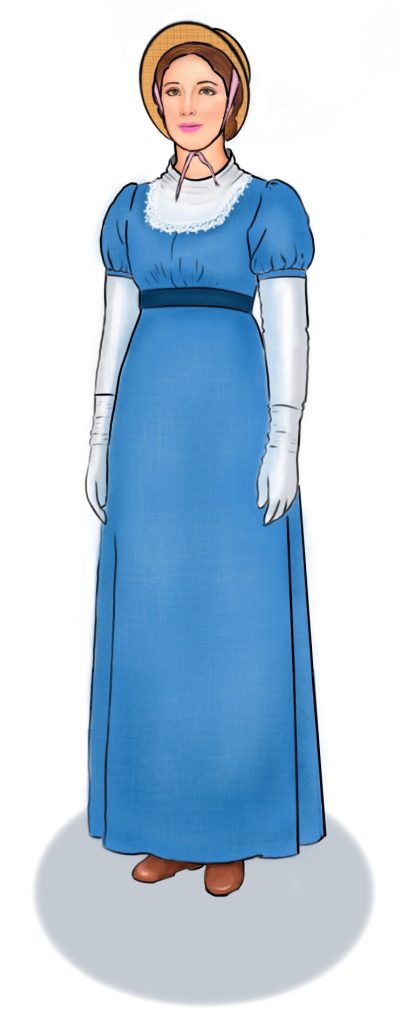

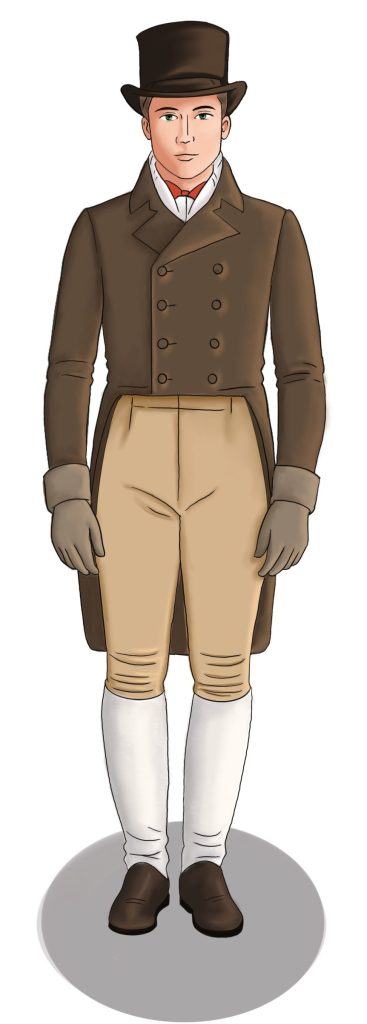

There is a particular set of English Country dances that were codified in a book written by John Playford in 1651CE in a book called the English Dancing Master.[5] These dances were commonly done by the aristocracy in the times of Jane Austin and other others of her day. These “Playford dances” have remained popular among people who belong to Jane Austin literary societies. When done in this context, the dancers often wear period costumes that are consistent with Austin novels.

- The Dressed Ship, a traditional ECD: https://youtu.be/kBqNfeKiLoY

- Haste to the Wedding at a period ball: https://youtu.be/8P0XBZDh-1g

3.3. Other kinds of English Dance

There are a few other kinds of folk dancing in England, although they are less common than Morris or English Country Dance. The first kind is clogging, which is found throughout the British Isles. Clogging, which is done with hard soled shoes is typically solo dancing, when the dancer creates a percussive noise with their feet. Clogging is probably one ancestor of modern tap dancing.

- English Clog Dancing: https://youtu.be/RvyJyVhXcaI

- Lancashire Clog: https://youtu.be/xxxRmIwyrOQ?si=oUr8PnGtw-mtq6ek

- Cornish Clogging: https://youtu.be/3TLgWCazmnc?si=kJB2hFxa7xdgTdWW

Another kind of English dancing is known as barn dancing. There is much cross border similarity between English barn dancing and Scottish cèilidh dancing and, in fact, sometimes barn dancing is even called ceilidh dancing in England. This kind of dancing is done at informal parties and community events. The dancers typically don’t know the dances and follow the instructions of a dance caller, as in American square dancing or contra dancing.

- English Barn Dance: https://youtu.be/20AzpUhcl_E?si=pOrhCCyz88cyXyWy

Stylistically there is not much difference between barn dancing and a third style called reeling. Both styles avoid the use of intricate footwork and focus on fast moving figures. However, there are two main differences between reeling and barn dancing. First, there is no caller at reeling events. The dancers are expect to know all the dances, of which there are a limited number. The dances tend to be a little more complicated than barn dances. Second, reeling is typically found at formal balls rather than at community events. There appears to be a class difference between barn dances and reeling events. While barn dances are open to everyone, reeling events, at least until very recently are associated with the aristocracy.

- The Royal Family doing reeling: https://youtu.be/uyVZCiPGeYQ?si=xo8lNvHHiwlW1V_V

3.4. Music for Dancing in England and Cornwall

Typically speaking, the instruments used for Morris dancing are a solo fiddle, a concertina or button box accordion, or a tin whistle. or some combination of those. Morris dancing is often done outside in impromptu locations, so the musicians play unamplified. Their instruments must also be portable as the Morris dance teams often move around and dance in different places during the course of one performance. The same kinds of musicians play for rapper dancers and cloggers.

The ensembles that play for English Country Dance are much more extensive. They often resemble classical music quartets and quintets. They will almost always have a fiddle player and a pianist. But you also find cellos, flutes, flageolets, and recorders.

Groups that play for Reeling and Cèilidh dances overlap with those that play for English Country Dance in terms of instrumentation, but you will often find the addition of accordions, electric guitars, synthesizers, and drum sets, to up the “party” feel of the barn dance.

4. Wales (Cymru)

Wales is a mountainous region on the west coast of Great Britain. Traditionally, people in Wales spoke Welsh (Cymraeg), a Celtic language. The dances of Wales are quite similar to those of the English. They primarily do set dancing and clogging. The instrumentation is also similar.

Welsh women’s costumes often consist of long skirts, scarves over the shoulder, covered hair, and sometimes tall top hats. The men wear breeches shirts and vests.

- Welsh Set dance: https://youtu.be/5_jMCsiYHTE

- Welsh Clogging: https://youtu.be/YGRn1XDYIVc

5. Scotland (Alba)

There are four main types of dancing in Scotland: Highland Dancing, Cèilidh Dancing, Step Dancing and Scottish Country Dancing.

5.1. Highland Dancing

Perhaps the most iconic of Scottish dancing is the Highland Dance. Highland dances (Dannsa Gàidhealach) are now most often presented as competition dances at highland games sporting events. They are probably descended from ritual dances of the Gaelic people. The steps and hand positions of the Highland Fling are meant to represent stags. Highland Dancing is usually done to solo bagpipe music. The dance style is characterized by very sharp balletic motions. The dancers dance almost en pointe, up on the balls of their feet. It is extremely athletic. Traditionally Highland Dancing was almost exclusively done by men, but now it is largely performed by women.

Both male and female Highland Dancers wear kilts. Female highland dancers sometimes have a second costume, which involves a tartan skirt that they use for dances that are traditionally associated with women (e.g., the Highland Lilt).

- The Highland Fling: https://youtu.be/CfE7jHThiUc

- The Sword Dance: https://youtu.be/YBSjZMMHSV0

5.2. Cèilidh Dancing

In Scottish Gaelic, the word cèilidh means a social meeting or socializing. This has shifted meaning a bit in Scots and Scottish English to refer to a party. So cèilidh dancing is party dancing.[6] Most cèilidh dances are done in couples to reels, jigs, and waltz. They often involve a figure where the couples are arranged around the room in a big circle, with a couple facing another couple. This is called “Sicilian circle” formation or “Circassian circle” formation. Each time through the dance, the couples progress around the room and dance with the next couple they meet. Other cèilidh dances are done in sets of 3 or 4 couples. The dancers typically use running steps. The dances are very free and quick; the Scottish comedian Danny Bhoy calls Cèilidh dancing “a cross between a dance and a fight”.[7]

- Cèilidh Dancing: https://youtu.be/xPDwO-M-VUE

- The Gay Gordons: https://youtu.be/g-uSDOjw5v8?si=kkdr0O_XArZI0ZNV

5.3. Step Dancing

Closely related to English Clogging is Scottish step dancing. It is most popular among Scottish Immigrant communities in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia in Canada. It is usually done solo with an emphasis on the percussive precision of the footwork.

- Leahy family step dancing: https://youtu.be/kqIZA-W1tLM

- Cape Breton Step dancing: https://youtu.be/Fb2A5H6gUMY?si=NLiLyKLVubJB1-2w

- Scottish Step dancing: https://youtu.be/KbDOA5NoEe4?si=e_C7-jUz_mMPgCB1

5.4. Scottish Country Dancing

The most formal kind of Scottish dancing is Scottish Country Dancing (SCD). It has a regulatory body called the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society (Milligan and MacLennan 1950). The footwork of SCD is much more complicated than that of English country dances, but the figures that the dancers do are similar. Like English Country Dancing, SCD is done in longwise sets. Unique to Scottish Country dancing is a particular dance called a strathspey, which is a syncopated reel, where the dancers dance with slow very precise steps.

Women do not wear kilts when doing SCD, they tend to wear shin-length white skirts and a tartan “plaid” over their shoulder. Men do wear kilts and all the finery when doing SCD.

- Mrs. Stewart’s Jig (SCD): https://youtu.be/ZnLVXkXhpiY

- Miss Gibson’s Strathspey (SCD): https://youtu.be/1EK3PeGsrhY

- Performance Medley of Scottish Country Dance: https://youtu.be/snuv9TeWGRY?si=PQKYG_T_QQkHynEP

5.5 Music for dancing in Scotland

Highland dancing is almost exclusively done to the solo highland bagpipe. Scottish Country Dancing is usually done to some combination of piano accordion, piano and fiddle, occasionally augmented with other instruments. Like English barn dance music, Scottish cèilidh music is also augmented with tin whistles, electric guitars, and synthesizers.

6. Ireland (Éire)

Irish dancing also comes in several different styles, which parallel those of their English and Scottish neighbors.

6.1. Step Dancing

Perhaps the most famous kind of Irish folk dance is the Irish step dance. It was made world famous by the Eurovision-winning performance, and subsequent touring show, known as Riverdance. The modern form of this dancing is done with very high kicks. It also typically requires that the arms are immobilized by the sides. When the dancers in Riverdance performed, they didn’t keep their arms by their sides and shocked the Irish step dance community.

The original style of step dancing was known as seán-nos, or old-style dancing. It is quite flat footed and the arms are allowed to be free. It is very similar to Scottish step dancing and English clogging:

The traditional costumes for Irish step dancing include kilts for the man, but in solid colors rather than tartans. Women traditionally wear one-piece short skirts and tops, often embroidered with Celtic designs. In recent years, these simple dresses have become more and more elaborate with neon colors, rhinestones, and elaborate hairdos.

- Modern traditional Irish Step Dance: https://youtu.be/_CP3t6SoiDw

- Riverdance Step Dance: https://youtu.be/FoHlrQScWl0

- Emma O’Sullivan Sean Nos: https://youtu.be/IYxRbgVfEqs

6.2. Ceilí Set Dancing

Ireland also has its tradition of set dances, called ceilí dancing – this is very similar to Scottish cèilidh dancing or Scottish Country Dances. In Ireland, ceilí dances are often done in squares rather than longwise sets. Each area of Ireland has its own “set”, for example there is a South Kerry Set, and a Donegal Set, etc. These sets are actually a collection or medley of dances. This is related to the tradition of French quadrilles, which were traditionally medleys of figures. Like Scottish Country Dances, the footwork of Irish ceilí dancing is quite complicated. Many of the basic footwork patterns of step dancing are included in Irish ceilí dancing too.

- Irish Ceilí dancing: https://youtu.be/vZ48lZl2rOY

- Claddagh Set: https://youtu.be/kn94A4otfAs?si=YBaPK0zXltanGrqG

- Kerry Set: https://youtu.be/7XRYQPFL6SA?si=cTaVmc7-Rs-n8f7t

6.3. Music for Dancing in Ireland

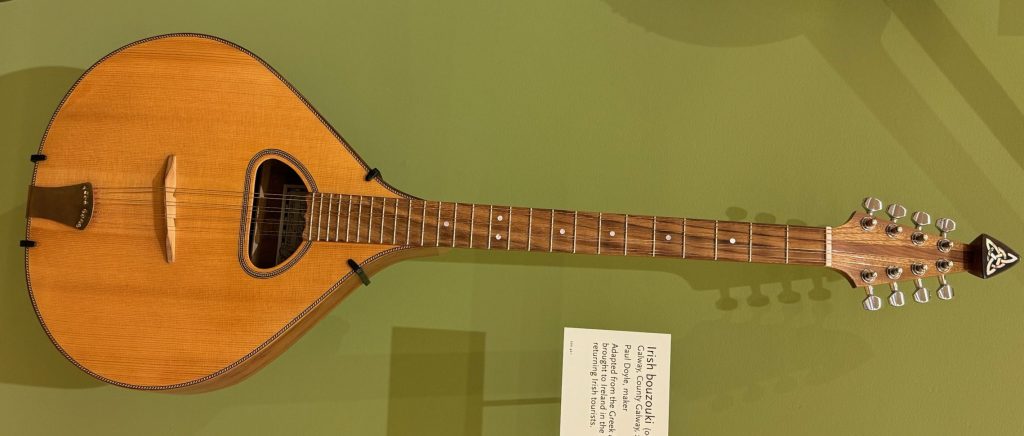

Irish music dance music features many of the same instruments as its Scottish, English, and Welsh cousins. You find fiddles, accordions, button boxes, banjos, concertinas, etc. But almost never does Irish dance music use the piano. Instead, you find a number of instruments that are specific to Ireland. Perhaps the most exotic is the uillean bagpipe. Unlike it’s cousin, the highland bagpipe, the bag is not inflated by blowing into it. Instead, the uillean pipes use a bellows under the R elbow (uillean is Irish for “elbow”). It also has a much more complex set of harmonic drones. Another typical Irish instrument is the Irish wooden flute, with its characteristic whispery sound and the six holed tin whistle. Irish music is also distinct because it regularly uses percussion, including the bones, the spoons and a frame drum with a beater called a bodhrán. Other Irish instruments include the Harp and the Irish Bouzouki.

- Uillean Pipes: https://youtu.be/4MxFsk4sYM4?si=UeddE7lhjEWcnNLR

- Wooden Flue: https://youtu.be/_1gM1SDYvSw?si=DD876Oc7NhxgLLA0

- Tin Whistle: https://youtu.be/GjEEmAN0uRY?si=KelkgK-KwX36eL-O

- Irish Spoons: https://youtu.be/jcAa6mOT6Lg?si=Ozolu9LeQmcPG_N8

- Bodhrán: https://youtu.be/dMI4X8OOMOg?si=xAuhciPr_YOokiN1

7. Isle of Man (Ellan Vannin)

Traditional dance on the Isle of Man, along with its Celtic language Manx, either disappeared completely or went underground in the 19th Century CE. The early 20th century saw a revival in both the language and the dances of the island. One woman, Mona Douglas, was responsible for gathering a mass of written evidence about dance traditions on the island and for talking to older folk who remembered some bits. Unsurprisingly, being in the middle of the Irish Sea between Scotland and Ireland, Manx dance had many features of the other two cultures. The dances were in done in couples and in sets.

One particularly interesting tradition was the dance called shelg yn dreean or “Hunt the Wren” which was traditionally done on St. Stephen’s Day (the day after Christmas). It is thought to be the remnants of ancient pagan ritual associated with collecting sacred feathers. Similar wren hunting traditions were found in Ireland and Wales. Recent folklore associates it with ridding the island of the effects of the witch Tehi Tegi who is said to turn into a wren on St. Stephen’s Day. Now there is no longer an actual hunt, but there is a traditional song and dance. During the dance, someone stands in the middle of the circle holding a “wren pole” which historically held the body of the hunted bird. The dance and song were thought to be lost, but the Mona Douglas noticed a group of children playing a game in 1925 she thought was connected and revived the folk dance based on this.

- Hunt the Wren: https://youtu.be/YXoplBXuyd4?si=z3D2r_IA5TWqDrVF

Further Reading

- Bacon (1974), Barclay and Jones (2015), Dunne (1995), Ewart and Ewart (1996), Moylan (1985), Murphey (1995, 2000), O’Rafferty (1954), Quinn (1997), Anonymous (1995), Burchenal (1913), Emmerson (1995), Flett and Flett (1979). Forrest (1984), Hamilton and Fraeley (1978), Karpeles and Blake (1951), Knight (1996), Knight (2012), Milligan and MacLennan (1950), Peck (n.d.) Pilling (2017), Playford (1651), Rippon (1993), Sharp (1911), Strathern (1984). See References section for complete citations.

Some Suggested Dances for Teaching

England and Cornwall:

- Eastbourne Rover: https://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2021/08/eastbourne-rover-england.html

- Bare Necessities: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2014/01/bare-necessities-england.html

- Well Hall: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2014/07/well-hall-england.html

- Hole in the Wall: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2014/07/hole-in-wall-england.html

- Plethyn Lulynn (Newlyn Reel): https://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2023/02/plethyn-lulynn-newlyn-reel-cornwall.html

Wales:

- Jig Y Ffermwyr (Farmer’s Jig): https://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2021/10/jig-y-ffermwyr-wales.html

- Robin Ddiog (Lazy Robin): http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2014/02/robin-ddioglazy-robin-circle-dance-wales.html

Scotland:

- Kingston Flyer: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2008/02/kingston-flyer-8×32-jig-scotland.html

- Flying Scotsman: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2018/06/the-flying-scotsman-scotland.html

- Gay Gordons: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2011/09/gay-gordons-scotland.html

- Canadian Barn Dance: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2014/01/canadian-barn-dance-scotlandcanada.html

Ireland:

- Walls of Limerick: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2014/03/walls-of-limerick-ballai-luimnigh.html

- Siege of Ennis: http://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2015/09/siege-of-ennis-ionsai-na-hinse-ireland.html

Isle of Man

- Shelg yn Dreean: https://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2022/12/shelg-yn-dreean-hunt-wren-isle-of-man.html

Discussion Question

Discussion Question 1.

The component countries of Great Britain and Ireland fiercely distinguish themselves from each other. Nevertheless, there are many similarities among the nations in form of dance (all have a kind of clogging or step dancing, all have a set dance tradition, and all have cèilidh/ceilí/barn dance party dance styles) and some overlap in instrumentation. In fact, you’ll often find exactly the same tunes being played in each of these countries for dance. But what are the differences among these traditions and how do they help manifest a notion of identity distinct from their neighbors?

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.1: Map of Great Britain and Ireland © John W. W. Powell. Additional geospatial data cited in map. Used here with permission

- Figure 3.2: Morris Dance Costume © Asma, used with permission

- Figure 3.3: Rapper Dancer © Asma, used with permission

- Figure 3.4: Rapper Swords in a Lock formation © Sam Overbeck, used with permission

- Figure 3.5: Women’s period costume for playford dancing © Asma, used with permission

- Figure 3.6: Men’s playford costurem © Asma, used with permission

- Figure 3.7: Concertina © Wiki Taro is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 3.8: Recorder © Andrew Carnie, personal collection

- Figure 3.9: Double Flageolet © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission

- Figure 3.10: Welsh traditional women’s costumes © Asma, used here with permission

- Figure 3.11: Scottish Costumes © Asma, used with permission

- Figure 3.12: Scottish Fiddle © Heidi Harley, Personal Collection, used with permission

- Figure 3.13: Highland Bagpipe © Andrew Carnie, personal collection

- Figure 3.14: Irish Step Dancing costumes © Asma, used with permission

- Figure 3.15: Uillean bagpipes © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission

- Figure 3.16: Irish wooden flute © Andrew Carnie, personal collection

- Figure 3.17: Irish tin whistles © Andrew Carnie, personal collection

- Figure 3.18: Consairtin/concertina © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission

- Figure 3.19: Bones © Art Torrance, personal colleciton. Used with permission

- Figure 3.20: Irish Spoons © Andrew Carnie, personal collection

- Figure 3.21: Bodhran and beater © Andrew Carnie, personal collection

- Figure 3.22: Cairdin/Button Box Accordion © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission

- Figure 3.23: Bouzouki, Ireland © Musical instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission.

- Figure 3.24: Irish Harp or Clarsach © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission.

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_British_Isles for a more in-depth history of the British Isles. ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morris_dance ↵

- For comparison, look at the costumes and props in this Romanian Caluşarii video https://youtu.be/emjF6iI5Wc0 The costumes are nearly identical, done by a people on the other side of Europe. ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Country_dance ↵

- http://playforddances.com ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cèilidh ↵

- https://youtu.be/1msu8iQT3kw ↵