Part 5: Dances of Anatolia, the Caucasus, and the Middle East

17 Dances of Iran and Central Asia

1. Geography and History

Although central Asia is not part of the middle east, Iran is, and there is a continuum of music and dance cultures that starts in Iran and extends eastward into central Asia. Central Asia includes Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. Pakistan and Afghanistan are also technically part of Central Asia, but I’m not going to discuss them here as their dance traditions are more closely tied with those of Mongolia, China and Indian Subcontinent. These regions are often connected to countries in Europe and the Middle East through language. Persian and Tajik are Indo-European languages. Turkmen, Uzbek, Kyrgyz, and Kazakh are all Turkic languages related to Turkish.

Iran, historically known as Persia, boasts a rich and complex history. The Elamite civilization, the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanian Empires were regional superpowers in their time. Apart from a brief period in the 3rd century BCE, when the was conquered by Alexander the Great, Persia was the main power base in the region. It was the heart of the first monotheistic religion (Zoroastrianism) which went on to be one of the most influential sources for the Abrahamic religions. In later years, the various Persian empires were in conflict first with the Greeks and then with Romans. In the mid 7th century CE, the region was conquered by the Arabs, who brought with them Islam. But the Persians retained their own language and many of their own cultural traditions. During the 8th to 13th centuries, Persia became a center of science, philosophy, medicine, and literature, contributing significantly to the Islamic Golden Age. From the Middle Ages to the 19th century, it was relatively independent.

While never a British Colony, the country fell under British influence at the cusp of the 20th century, particularly because of Britain’s increasing need for resources. During the Pahlavi Dynasty, the Shah of Iran tried to implement modernization and secularization, but the Shah’s rule was best characterized as oppressive and authoritarian. As a consequence in the late 1970s, a revolutionary movement developed to overthrow the Shah. Initially this was a secular revolution led by leftists, but it was soon overtaken by a radical Shia fundamentalist movement led by Ayatollah Khomeini, which in turn led to the theocratic Islamic Republic that rules Iran today.

Iran is still a very important regional power, but it is frequently at odds with the West, with its neighbors Iraq and Saudi Arabia and with Israel. It fought a terrible war with Iraq between 1980 and 1988. At the time of writing this, Iran is on the verge of achieving nuclear arms and is a thorn in the side of US policy in the region.

Among the countries that historically fell within the sphere of influence of Persia we find the nearby central Asian countries. Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan were all important parts of the Silk Road which connected Europe and the Middle East to the far East. All of these countries were conquered during the Mongol invasions of the 13th century CE and were part of the Timurid Empire. The influences of Mongol culture are still seen in the dance and music cultures of these nations, which show significant influences of Mongolian music and dance – not to mention economies historically connected to nomadic horse-oriented cultures.

In the late 19th century, all of these countries started to fall under the control of the Russian Empire and with the establishment of the Soviet Union, they all became Soviet Socialist republics. While the collapse of the USSR in the 1980s and 1990s gave hope for new democracies in the region most of these countries have retreated into authoritarian dictatorships based on Stalinist style cults of personality. In particular, the regimes of Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan have been noted for their authoritarian and oppressive regimes. Turkmenistan has often been compared to North Korea for its isolationist and inward looking philosophy with massive censorship and a complete lack of political opposition. Kyrgyzstan has been the one country moving away from authoritarianism. Since 2010, Kyrgyzstan has worked to establish a more stable parliamentary democracy, though it continues to face challenges related to corruption, economic development, and ethnic tensions.

2. Traditional Clothing

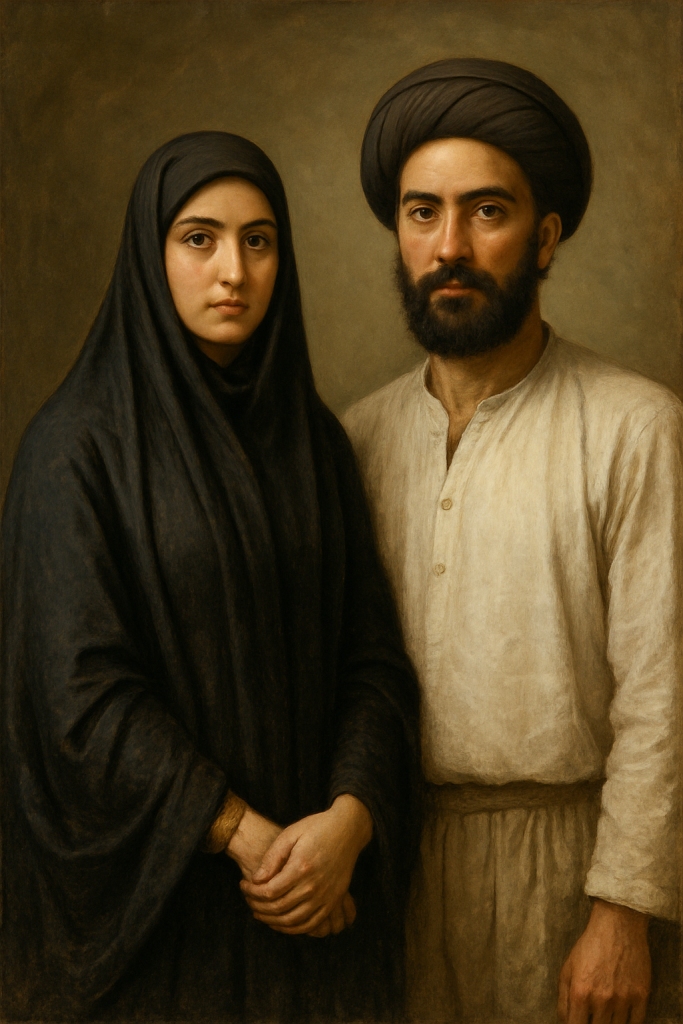

Iran is actually a multiethnic country; you have Kurdish people in the west, Azeris and Armenians in the north, and various tribal groups in the east and south in addition to the people who identify as Persian. So, there is some variation in what is worn in the various regions, but there are some general themes. The men often wear loose fitting baggy pants (شالوار), a long shirt (کمیز), a vest, and either a cap (کلاه) or turban (عمامه). They often wear a thick belt around the middle called a kamarband (کامرباند)– which gave rise to the cummerbund, now part of formal wear in the west. The most traditional costumes for women include a colorful floor length skirt (شلیته), a long blouse, and a vest. Women also wear a headscarf (شال) and sometimes a decorative belt. After the Islamic revolution, women were required to wear chador (چادر), which was a floor length black head covering and robe. Today, women often wear a long coat with long sleeves called a mânto (مانتو), along with a loose head scarf and pants.

The folk costumes from Central Asia bear the influences of their Persian, Caucasian and Asian neighbors. Women traditionally wear a long-sleeved dress (variously called koylek, khan atlas, kurte) with a fitted bodice and a flared skirt, often adorned with intricate embroidery. Over the dress, a sleeveless velvet vest (kimeshek, chyrpy, chyptama) is worn, which is also richly embroidered. They wear slippers or boots to dance in. A headscarf or elaborate headdress completes the outfit. Men have a long robe (chapan) worn over a shirt and trousers. The chapan is often brightly colored and embroidered. Since the cultures are highly equestrian, men typically wear long boots. Men and women can both wear a squared off skullcap (variously called toqi, tubeteika, tyubeteika, or doppa). But men have other options including turbans, and felt caps called kalpak. In Turkmenistan the men are are most well-known for the large sheepskin hat (telpek) which is also found among their neighbors across the Caspian Sea in the Caucasus.

3. Music

There are two kinds of traditional Persian music. There is the classical Persian music which is noted for its complex meters and exotic modes (musical scales), which use among other things quartertone tuning. The classical music is associated with urban contexts. On the other hand, there is also folk music, played in less formal context and used in the village for dancing. The structures in the folk music tend to be simpler and repetitive. The songs also tend to be more about everyday life, whereas the classical music is often tied to Persian poetry and spirituality. The two musical forms, while distinct, obviously have influenced one another. Traditionally the folk music tradition used fewer instruments (like the zurna and a dohol drum), where the classical music used more complicated string instruments like the tar, santur and more genteel percussion like the daf. Today, one finds the traditionally classical instruments also playing folk music and music for dancing. As in most parts of the world one also finds more and more electronic influence on the folk traditions with synthesizers and guitars playing a more prominent role, especially at festivities like weddings.

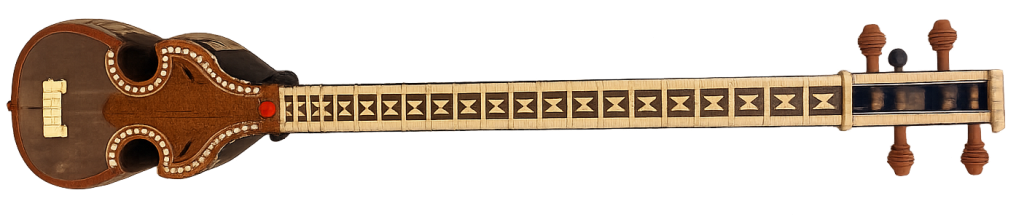

The instruments used throughout the region include some plucked string instruments like the tar (تار), which is a pear-shaped lute with 6 strings, the setar, which is a smaller instrument with just 4 strings. Similar plucked lutes are the manzur from Uzbekistan, the saz, which is also played in Turkey, the komuz (3 strings), and the dutar/dotar (2 strings).

- Video of tar: https://youtu.be/TvKp25tgJ-I?si=lB9ew5lfXOyeQU92

- Video of setar: https://youtu.be/N2ezrR-m1OA?si=GZpm4KhxNEuB5KRL

- Video of dutar: https://youtu.be/jHRiO4wHC6A?si=2Vz2Okh79WpryiHK

- Video of komuz: https://youtu.be/9-W9FvF9P6o?si=_RRe7SW8fM63n2sO

One finds hammered string instruments throughout Europe and the middle east. The Persian and Central Asian variety is called the santur (سنتور). It’s a hammered dulcimer with a trapezoidal wooden body and metal strings. It is played with two small hammers.

- Video of Persian Santur: https://youtu.be/95amB7kUu-k?si=8ZF-iDyrMwIuMMtH

Bowed instruments are also found. The kamancheh is found throughout the region. It, along with its close cousin, the ghijak, is a spike fiddle with a round body.

- Video of classical Persian tar and kamancheh: https://youtu.be/G4DYMX1NUQY?si=gfnaSsvrDRFM5tJU

Probably originating in the Caucasus, the duduk/tuiduk/туйдук/düdük is a doubled reeded wind instrument. One also finds other reed instruments like the oboe-like surnay/zurna which is also found throughout the region (see the chapter on the Caucasus for a picture). An end-blown 6 fingered flute, the ney ( نی), is also found throughout the middle east and central Asia.

- Video of Persian Ney: https://youtu.be/dKFjixNeL5s?si=BuwC5tQoikd7raT8

The daf (دف) is a large frame drum covered with goatskin and played with the hands. It is also found in Anatolia and the Caucasus. The dayereh and doira are frame drums related to the daf with metal rings inside its circular wooden frame. They are played by shaking or striking with the fingers or palm and are used in folk and classical music. The tonbak/zarb (تنبک) is a goblet-shaped drum made of wood with a goatskin head. It is played with the fingers and palms of both hands and is central to Persian classical music and rhythmic compositions. Finally, we have the naqareh, nogora or nagara kettle drum made of metal or wood with a goatskin head. It is played with sticks and is mostly likely an import from the Indian subcontinent.

- Video of Persian daf: https://youtu.be/cWy0PeosPEg?si=PC7d_C9rKPsMiZNo

- Video of Uzbek nogora: https://youtu.be/boDOeWT7G68?si=ZMbUlU7BEVMqg8xd

- Video of Persian santur and tonbak: https://youtu.be/FWadPYy1_Cw?si=kLIgiihPc0eSRfNM

4. Dance

4.1. Dance in Iran

Among the majority Persians in Iran, the most common style of traditional dance is a solo dance style distantly related to raqs baladi style belly dance called ghajar or raghs-e-shamim. This style is associated with Persian classical music. It is primarily done by women, but they wear conservative dress. It is characterized by flowing movement of the upper body and flowing snaking hand gestures. Unlike belly dance, there are no gyrations of the hips or lower body, but the dancers spin around and twist their upper bodies.

- Video of Persian classical dance: https://youtu.be/boErIHMg4gA?si=YYD-gQl7BiZMh1vO

- Video of Persian classical dance: https://youtu.be/Vsgf5qoSGuA?si=nnfTIkufF2jg6uJq

- Video of raqs-e-shamim done to more modern music: https://youtu.be/bkqq6EMG5Uw?si=pUG5VKDZYPuhCLBl

These days the religious authorities disapprove of dancing in public, especially when the genders are mixed. In 2023, several people were arrested for public dancing in Tehran. Things appear to be less strict among ethnic minority communities.

Bandari dancing from the south of the country is more like traditional belly dancing. It’s a lively dance characterized by energetic movements, often performed by women, featuring swaying hips and vibrant but covering costumes. Unlike classical Persian dance, bandari dancing often involves hip and shoulder gyration.

- Video of bandari dancing: https://youtu.be/Zgbg8USYbuI?si=ZbFU2hg0xFshweVX

- Video of bandari dancing: https://youtu.be/on7dHURYR54?si=3ctbc52fGh4cTYzU

The dancing of the Kurds is discussed in more detail in the chapter on Anatolia, but there are Kurds in the west of Iran too. So, I’ll briefly mention them here. Like their cousins in Iraq, Turkey and Syria, the Sorani Kurds of Iran dance in lines holding hands closely together. The dance lines are gender-segregated as would be expected in conservative Iran.

- Sorani Kurdish dancing: https://youtu.be/Qq4J6cTCqms?si=LC_2jEMtCiIGdbfF

There is also an Azeri minority living in the north of the country. Their dances are very similar to those done in Azerbaijan (see the chapter on the Caucasus).

- Azeri dance in Iran: https://youtu.be/7VnmEDxgP9w?si=lsxrQNG2nqCCcmxT

There are several minority groups that live in the southwest of the country. These include the Lori/Luri, who speak an Indo-Aryan language and the Qashqai, who are a Turkic speaking group who claim to be originally from Azerbaijan. The dance styles of these people often involve a circle of solo dancers who wave silken handkerchiefs as they dance. This is indeed reminiscent of some of the elegant arm motions found in Caucasian dancing.

- Qashqai Dance: https://youtu.be/9VEUUPFjbZk?si=OWf0xR_W7600DMlZ

- Qashqai Dance: https://youtu.be/4yih9JbRACY?si=z3Xd5J5CULzSPDmr

- Lori Dance: https://youtu.be/TOd6rFKs2nk?si=JY-3kIHhW8Fhq4qE

- Raqs e Chupi (رقص چورپی): https://youtu.be/jR146a4ZUO0?si=7agvuJXwDa9QONnm

The tribal groups in the far east of Iran, centered around the town of Torbat-e Jam, have their own unique style of dance. Done as a circle of individuals, typically holding sticks, they circle around with acrobatic moves creating rhythms with their feet and the sticks.

- Torbat Jam: https://youtu.be/Ks4bVrCHHY4?si=ysgSKe35-oCFmnxX

- Torbat Jam: https://youtu.be/CySadqOKoGI?si=IcN8KDcvu40dndCi

4.2. Central Asian Dance

Being at the crossroads between the Middle East, the Caucasus and East Asia, it should be no surprise that the dance styles of Central Asia is also a mélange of the styles of dances from these various regions

One dance found throughout central Asia is the Lazgi/Lezgi/Лезги which is claimed as a traditional folk dance by the Uzbeks, Tajiks, and Turkmens. It is clearly related to the Lezginka of the Caucasus.

- Uzbek Lazgi: https://youtu.be/osYmd8Z4LtY?si=0DZASzmIozDKfyWw

Influences from the other direction are seen in the horsemen-style dances that likely came with the Mongols. The national dances of the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz peoples is the Kara Zhorga/Kara Jorgo/Кара Жорго or “Black stallion dance”. This style of dance is characterized by sharp movements of the body, particularly of the shoulders and head combined with smooth arm gestures. It is very similar to the Meshrep of their Uyghur neighbors in China and the Biyelgee, which is the national dance of Mongolia.

- Kara Zhorga: https://youtu.be/KzN28CcfHGY?si=N2VvY9jcy3IZjARl

- Kara Zhorga: https://youtu.be/77NnDv8pemM?si=H8zZWK7agPIrI-Wf

- Kara Zhorga: https://youtu.be/J2V9DtAGBAU?si=QRas21GYAZ-UHv6e

- Mongolian Biyelgee (Биелгээ): https://youtu.be/nqKyUMXq4V4?si=bSRjneXnUbFDrPPm

- Uyghur Meshrep: https://youtu.be/1Hef5OXHr5I?si=r0VYL-WQq14MsRYp

Further Reading

- Shay (2022), Shay (1999). See references for full citations.

- https://kyrgyzstan-tourism.com/blog/kyrgyz-traditional-clothing/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luri_dances

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Torbat-e_Jam

Some Suggested Dances for Teaching

- Raqs E Churpi: https://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2016/09/raqs-e-churpi-iran.html

- Kara Jorgo: https://folkdancemusings.blogspot.com/2022/07/kara-jorgo-kara-jorga.html

Media Attributions

- Figure 17.1: Iran and Central Asia © Mapchart.net is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 17.2: Persian costumes

- Figure 17:3. Kazakh traditional costumes © Saman Meihami, assisted by ChatGPT. Used with permission

- Figure 17.4: Uzbek Doppa © Saman Meihami, assisted by ChatGPT. Used with permission

- Figure 17.5. Women’s Tubeteika skull cap, Tajik © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission

- Figure 17.6: Uzbek Costumes © Saman Meihami, assisted by ChatGPT. Used with permission

- Figure 17.7: Chapan Costume, Uzbekistan © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission

- Figure 17.8: Turkmen telpek © Saman Meihami, assisted by ChatGPT. Used with permission

- Figure 17.9: Kyrgyz folk costumes © Saman Meihami, assisted by ChatGPT. Used with permission

- Figure 17.10: Tar, Azerbaijan © MrArifnajafov is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 17.11: Setar © Shabdiz is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Figure 17.12: Dotar © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with Permission.

- Figure 17.13: Manzur Uzbekistan © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with Permission.

- Figure 17.14: Santur from Iran © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission

- Figure 17.15: Kamancheh © Metropolitan Museum of Art is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Figure 17.16: Daf © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with Permission.

- Figure 17.17: Tonbak drum © Opinoki is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 17.18: Doira, Tashkent Uzbekistan © Musical Instrument Museum, Phoenix. Used with permission