Part 7: Folk Dance Fundamentals and Terminology

23 Holds and Configurations

In this chapter, we will discuss some basics of folk dance terminology. Like any area of study, folk dancing comes with its own specialized jargon which can be a bit mysterious. Here, we look at some key ideas about hand holds and dance configurations that will help launch you into dance success. There are four sections in this chapter: one on solo dances, one on circle dances, one on couple dances and finally one on set dances. In the next two chapters, we’ll look at some basic footwork and figures.

1. Solo Dances

In a lot of cultures dances are often done solo, not with a partner or in a group where people interact with each other. For our purposes solo dances are the ones that aren’t done holding hands, don’t involve interaction with a partner or don’t move in a line or circle with other people. You find these dances all over the world, from the classical dances of Sri Lanka to the Hula in Hawai’i to the country and western line dances of the USA.

One super confusing piece of terminology in folk dance is the phrase line dance. In the context of the USA, the term refers to a kind of solo dance. There’s a whole tradition of solo line dances done to country and western music (e.g. Boot Scoot and Boogie), Disco (The electric slide), or really to any other kind of music. The reason these solo dances are called “line dances” is that they typically are done in several lines of people all starting facing one wall. The term is really confusing though, because in the context of Eastern European and Middle Eastern dances, the term line dance refers to either dances done in short straight lines, where the dancers are holding hands, belts or shoulders or to dancers dancing in circles and semi circles holding hands in various positions. Because of this ambiguity, I’m going to try to avoid the term line dance without a qualifier (like “American Line dance” or “Short Line dance”). But you should be aware that there are multiple meanings for this term.

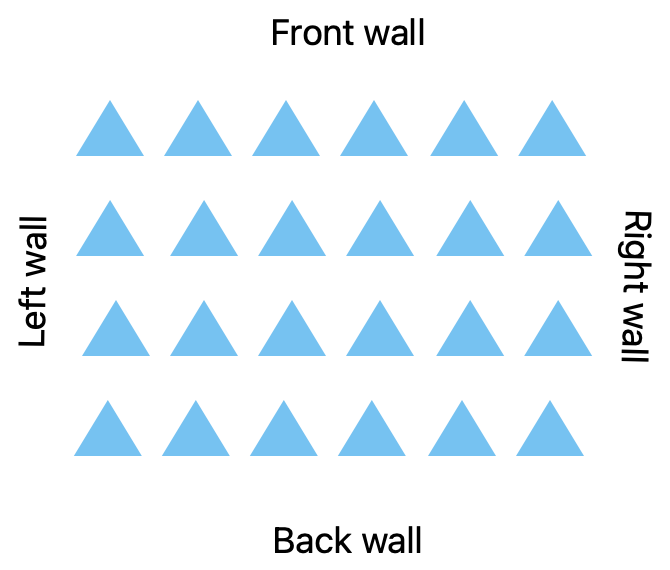

Within the American line dance tradition, there’s a set of terms that help you understand your orientation relative to spaces in the room, but these terms can actually be helpful when describing solo dances from any country. One-wall dances are dances that begin and end facing the same wall – if the room you’re in has mirrors, then it is typically the mirrors, but that wall could also be where a stage is, or where the musicians are sitting if you have live music. You may well turn around and temporarily face other directions during a one wall dance, but you always start the sequence facing the same wall. Two-wall dances are much rarer. These are dances where you start facing one wall the first time through the dance but the second time through the dance you start facing the wall that was behind you (i.e., the wall opposite the one you began the first time through. In two-wall dances you alternate between facing the front wall and the back wall every other time through the dance. To my knowledge, there are no 3 wall dances, but four-wall dances are extremely common. In four wall dances, start facing the front wall. The next time through you will have made a ¼ turn to start facing either the wall that was on your right or the wall that was on the left – depending upon the dance. The next time through you face the back wall, then the time after that you face the final wall. In between you might actually face many directions, including some quite complicated moves to get you to face the relevant wall at the end of one time through and the beginning of the next.

2. Short Line, Open, and Closed Circle Dances

Dances where you hold hands with other people and do the same step together are documented throughout all of Europe and into the Middle East. In Western and Northern Europe, they are relatively rare, apart from a few pockets (e.g., Brittany and the Basque country). In those regions, couple or set dances predominate, but you still find the occasional circle dance, which suggests it may represent an older tradition in these areas. But in the Balkans and the Middle East, dances where you hold hands with your neighbors in a circle, semi-circle or a line are the norm.

There are really three types of these dances: Dances done in short lines, dances done in open circles (or semi circles) and dance done in closed or complete circles. These dances are all done in a variety of hand holds.

2.1. Short Lines

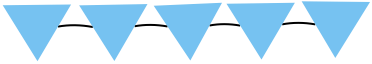

Dances from Turkey, the Caucasus, and some places in the Middle East such Lebanon and the Emirates are often done in short lines of about 6-10 people, although you can find them throughout the Balkans as well. Often dances of this form are done in hand holds which are not terribly comfortable when done with a larger group, such as the Shoulder or T hold and the back basket hold – we will have more to say about these holds below. Short line dances were also often done when the dancers had relatively little space to move. For example, among the Pomak (Muslim) Bulgarians, the women were expected to dance in very small groups on a balcony. Because of the limited space, these dances were always done in short lines.

2.2. Open Circle/Semi-circles

Perhaps the most common dance formation in Brittany, The Balkans, Turkey, and the Caucasus is what we call an open circle. This formation is also found in some dances throughout the rest of Europe too, you find dances like this in Sweden, France, Sardinia, the Basque countries too.

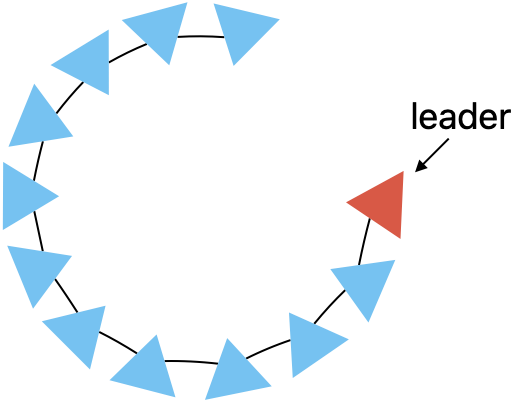

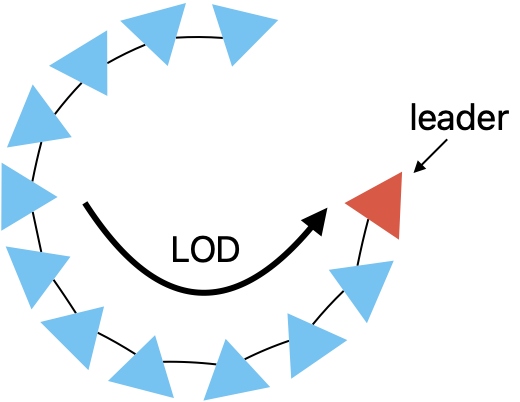

An open circle (or semi-circle) is a roughly circular formation of dancers holding hands with their neighbors. What makes it an “open circle” is that there is always a break in the circle. This allows the leader of the dance (see section 2.5) to spiral the line of dancers into the center or to snake the dancers around the room.

As mentioned above, this open circle formation can confusingly be called a “line dance” too because an open circle amounts to a line of dancers. It differs from American line dances in that the dancers always hold hands in an open circle dance. You’ll often hear folk dancers say things like “form a line” when they mean “form an open circle”. This terminology is very common, if confusing. In dances with Orthodox or Islamic religious traditions (e.g. most of the Balkans), the leader stands on the R end of the open circle as in the diagram above. In cultures that come from Catholic or Protestant traditions, the leader stands at the other end on the left.

2.3. Closed Circle Dances

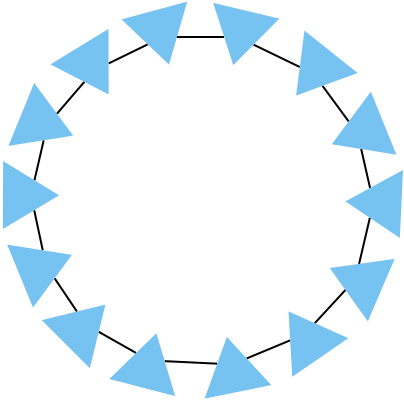

In Romania, Hungary, Croatia and a few other places, there are many dances that are done in closed circles. They obviously differ from open circle dances in that there is no break in the circle. These dances only travel around to the right or left (or very occasionally in and out of the circle).

Just to make life exciting, the term “circle dance” is also ambiguous depending upon the cultural context. In late 1976, Bernard Wosien was invited to the spiritual/ecological community in Findhorn in Northern Scotland to teach dances with a spiritual bent. This began the tradition of modern Sacred Circle Dancing (Helige Tanze), which has now spread around the world. These dances are all modern choreographies, but many are done to traditional music and are done using styling and motifs borrowed from Folk Dances. Many groups since have dropped the “Sacred” from the name and now just go by “Circle Dance”. In South America it is known as “Danza Circular.” Sacred circle dances are usually done in closed circles, and they may or may not involve holding hands with neighbors in a circle. A similar fact is true of modern Israeli dances. Older Israeli dances often drew upon the traditions of the Balkans and they did dances in circles holding hands with their neighbors. But Israeli dances today are almost always done in circles of individual dancers who don’t hold hands with their neighbors.

2.4. Hand Holds in Circles, Open Circles, and Lines.

When dancers hold hands in lines and circles, there are a surprising number of ways to connect up with your neighbors. Perhaps the simplest hand hold is to take hands with your neighbors’ hands and hold them down by your sides. This is often called V position because the shape of your joined hands with your neighbors forms a V. This is sometimes also called hands down. One common variant on V position involves swinging the arms gently forward and back on each count.

Another very common hold has the hands joined up at shoulder height, with the elbows bent. This is called W position because your hands form a W with your neighbors. Some teachers will also refer to this as hands up.

When dancing in W position in Balkan dancing, the most common way to connect with your neighbor is to have your right hand fingers pointing up and then your left neighbor rests their left hand on top of the notch created by your thumb and fingers.

A slightly different way of holding hands is found at the two extreme ends of Europe. In Brittany and in Turkey and Armenia, instead of holding hands you link little fingers (pinkie fingers) with your neighbors (pinky finger hold)

If you take the W position but extend your hands way above your head with the elbows straight, you have what is called Y hold. This hand hold is relatively rare because it’s not particularly comfortable to hold your hands up like this for a long period of time, but you do find it, particularly in the dances from along the Black Sea in Turkey.

In Black Sea dances, they not only hold their arms up above their heads, but they also hold hands in a unique way (Black Sea hold). You rest the palm of your right hand on the back of your neighbor’s left hand, and you let your wrists droop and your fingers point downwards towards the floor.

To round out our alphabet of holds, we have what’s known as T position or Shoulder Hold. In this hand hold you rest the palms of your hands on your neighbor’s shoulders. You find this hold all over the Balkans, particularly Romania, Greece, and Macedonia, but it has fallen out of favor with international folk dancers, because –if done wrong– it can be quite painful for your neighbors. You must support the weight of your own arms and not pull down on your neighbors. It’s also quite hard to do if you have people of different heights standing next to one another. In some countries, e.g., Macedonia, this hold is often thought of as a “men’s hold”, where a line of men will use shoulder hold, but a line of women doing the same dance will do it in W position.

A nice hold for slow walking dances is the escort position. When a dance rotates to the right, you put your left hand on your hip or rest it across your stomach. Your left-hand neighbor then hooks their right hand into the crook of your left elbow.

A variation of the escort is found in Greece. In Greek escort position you hold your left hand palm up slightly in front of stomach. Your elbow is bent, and your forearm is parallel to the floor. You then tuck your right hand through into the crook of your neighbor’s left hand but instead of hooking it into their elbow, you rest it palm down on their upwards pointing left hand.

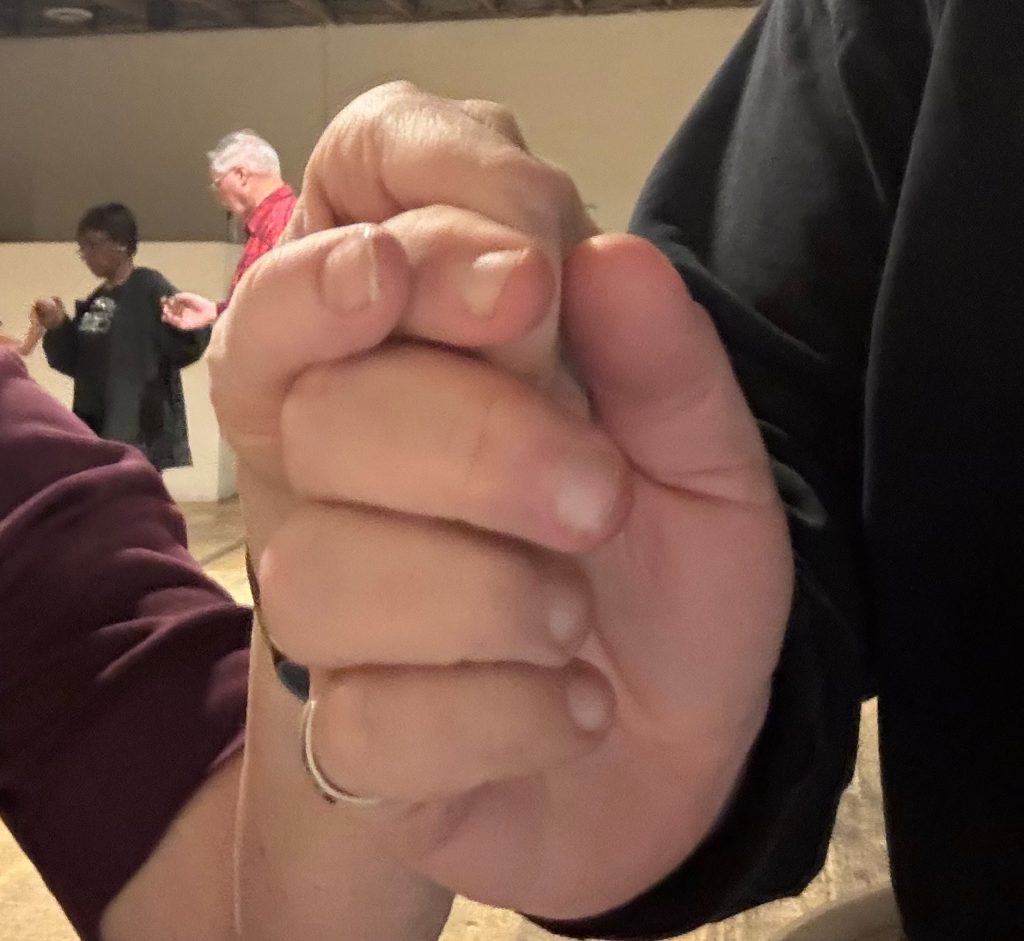

In Turkey, the Caucuses and a lot of the Middle East, there is a special hold where the dancers stand extremely close to each other with shoulders touching each other, or even with the right shoulder slightly behind your neighbor’s left shoulder. In Turkey the hands are held straight down and slightly behind backwards There’s no standard name for this position, although the Turkish Dance teacher, Bora Özkök, used to call it gluglu position (think being glued in right next to your neighbor). The Kurds do a variation of this hold, but instead of the hands being straight down, in Kurdish position, they are bent at the elbow with the forearms parallel to the floor. In both gluglu and Kurdish position, you typically hold hands by interdigitating with your neighbors – that is, you go palm to palm with your neighbor and interlace your fingers between theirs.

In the Balkans, there are also a few holds where you don’t actually hold hands with your immediate neighbors. Instead, you hold hands with the next people beyond your immediate neighbors (your penultimate neighbors, if you will). The most common version of this the front basket hold, so called because when you look at a line of dancers in this position, it looks like they are forming a basket weave. You lay your right hand on your immediate right-hand neighbor’s stomach. You then reach out with your left hand and take the right hand that’s waiting there for you. This hold forms a very tight circle or line. One common mistake that new dancers often make when forming this hold is they try to cross their own hands in front of their bodies. Don’t do this! Extend your right hand to your right and your left to your left. One special restriction on this hold is determined by the main direction of travel in your circle. If the dance travels primarily counterclockwise, you typically put the left arm over (on top) of the right. If the dance travels primarily clockwise you put the right arm over, and the L arm under.

An interesting variation on the front basket is the belt hold. The hands and arms are held in almost the same position as the front basket, except you hold your neighbor’s belt instead of holding your penultimate neighbor’s hand.

Another variant is the back basket hold. This is the same as the basket hold, except your hold hands with your penultimate neighbor behind your immediate neighbors back, instead of in front.

2.5. Line of Direction, Facing direction, and Leading an Open Circle or Line Dance

It is important in describing circle and open circle dances to talk about the direction(s) of motion. Some directions are very obvious. For example, many circle dances involve motion into the middle (or center) of the circle. Typically, this is paired with motion away from the middle/center. We also find dances that travel in a sawtooth pattern, that moves in towards the center except on a diagonal also moving slightly to the right or to the left. We call this in on the right/left diagonal or out on right/left diagonal. A less obvious set of directions govern motion to the right (or counterclockwise (CCW) motion) or motion to the left or (clockwise (CW) motion). These are often defined in terms that refer to the leader of an open circle or circle. The leader is always an experienced dancer who knows the steps really well. The leader may well call out or signal changes in the dance steps. They are also typically the dancers that everyone watches to stay synchronized and to be sure they are doing the right steps. In a closed circle dance, the leader could be anyone – it’s just the person that everyone knows is the best dancer. In open circle dances from the eastern Balkans, the Caucasus, and the Middle East, where the dances typically have counterclockwise motion, the leader is usually the person at the right most position. This is sometimes known as the head of the line. The other end is known as the tail. The exact opposite configuration holds for open circle dance from the western Balkans, France, and northern Europe. In those regions, where the open circle dances typically have a majority clockwise direction, the head of the line (and the leader) are in the leftmost position. There are some dances, typically short line dances from Turkey, where the leader isn’t on the end, but is dead center in the middle of the line. But this is relatively rare.

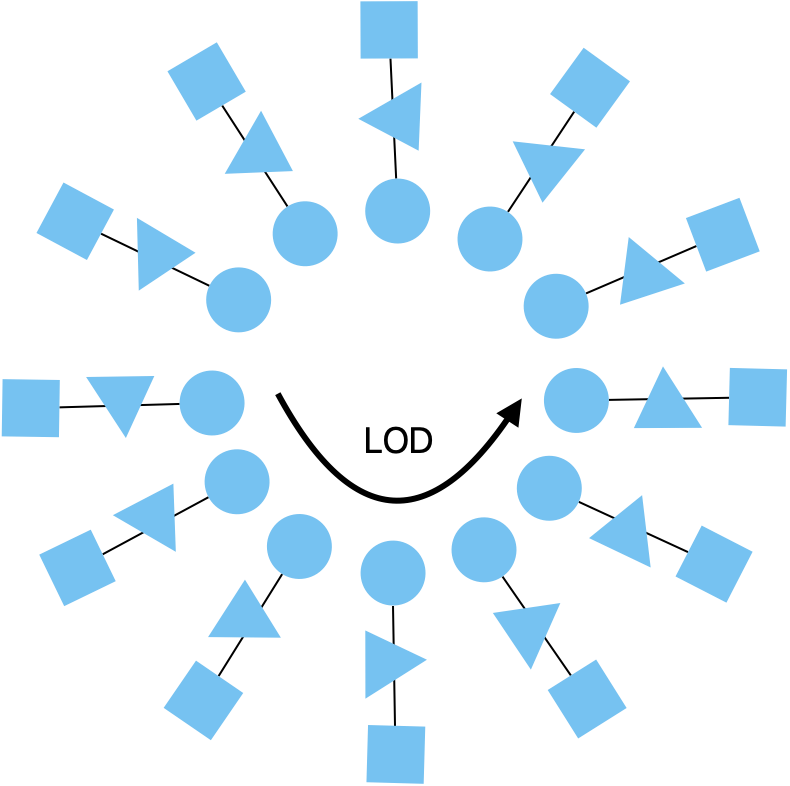

There is a set of terms out there that are used inconsistently, which can cause some confusion. These are Line of Direction (or LOD) and Reverse Line of Direction (RLOD). Technically speaking, line of direction refers to the side of the dance that is the head or where the leader is. If the leader/head is on the right, then the LOD is to the right (i.e., counterclockwise). If the leader/head is on the left, then the LOD is to the left (i.e., clockwise). RLOD is the opposite direction to LOD, whatever that is. What I’ve just told you is the technically correct way to use these terms, but unfortunately the usage of LOD and RLOD isn’t always consistent in international folk-dance circles. For many international folk dancers, the term LOD has become synonymous with counterclockwise, and the term RLOD synonymous with clockwise, no matter what side of the line the leader stands on and no matter what majority direction the circle, line or open circle moves in. This can be super confusing to new dances, so I will try to be clear what I mean if I use the terms.

Another important part of describing the motion of circle and open circle dance is the direction your body faces. This may or may not be the same as the direction of motion. So, for example you might be facing counterclockwise (CCW), but your actual motion may involve backing up clockwise (CW). If we say you are facing CCW or LOD, that typically means you are in a single file completely facing that way. But CCW motion (or motion in LOD), often involves facing center but moving to your side, or facing about halfway between facing center and facing completely in LOD. We often refer to this intermediate body position as facing slightly right (or left) of center. The terms forwards and backwards always refer to the facing direction. So, if you are facing into the center and you’re told to walk forward, you walk in the direction you’re facing. If you’re facing LOD and you’re told to walk backwards in RLOD, then you back up. One minor exception is when you are facing slightly right/left of center. If told to walk forward in this position the direction is ambiguous, that could mean walking in on the right diagonal, or it could mean moving in LOD. Again, I’ll try to be clear what I mean when I use these terms.

2.6. Circle Dance Etiquette

Whenever you are doing a physical activity with other people, whether it be riding bikes in a group, racing cars around a track, or doing circle and open circle dances, there are unspoken rules of etiquette that ensure that the group functions well together.

Some of these rules should be self-evident, but bear repeating anyway because you do occasionally run into people who either don’t know these principles or choose to ignore them, thus disrupting the good functioning of the line or circle dance and making the dance less enjoyable for others. First, don’t be a physical burden on your neighbors. For example, in a shoulder hold you must hold your own arms up and not put all your weight on your neighbors. Another example is not slowing down the circle if it is moving too fast for you, it’s better to step out of the circle than to have your neighbors dragging you along. Similarly, if you find you are constantly going the opposite direction of your neighbors, then you might want to step out of the main line so that you’re not bumping into people. If the dance involves swinging your arms, don’t resist! Let your more experienced neighbors swing your arms for you. If you resist the arm swinging of your neighbors you are in danger of hurting yourself or your fellow dancers, best to just go with the flow.

Speaking of leaving the circle there is an etiquette to that too. First check that no one is directly behind you. Second, do your best to help the people on either side of you join together to fill the gap you created. If they are standing close enough, you can even bring their hands together as you step back.

Joining a line is more complicated. You may want to inquire about the speed and difficulty of the dance before you join so that you don’t get pulled in many directions and slow other dancers down. In most folk dance groups, the other dancers will encourage you to join accessible dances and let you know when you shouldn’t join a dance because it is just for the hotshots and if you joined you might get in the way. If you are dancing with an ethnic community, it’s also important to just watch a bit before joining the dance. Sometimes, for example, someone might have paid the musicians to play a particular dance for them or their friends or sometimes at weddings a particular dance is restricted to a particular group of family members, and it would be inappropriate for an outsider to join. Another good rule of thumb is if you don’t know a dance or don’t recognize the music dance behind the line/circle behind an experienced dancer and follow their foot work until you are confident, then join the line after asking if you can.

Where you join into a circle or open circle dance is a much more context sensitive thing. If you are dancing with an international folk dance group, and the dance is an open circle, there’s a pretty good chance that the dance moves counterclockwise and the head/leader of the line is on the right edge. You never join in front of the leader. That is considered very rude. You are also taking on the responsibility of being the leader of the dance! With international folk dancing in the USA and Europe, you will be safe joining at the tail (or end) of the line (that’s usually the left end). When dancing in some ethnic communities however, joining at the tail of the line is just as rude as joining at the head. For example, in Serbian communities, the person at the tail end of the line is just as important as the person at the head – they are known as a second leader. In Serbian dances, you always join somewhere in the middle, but here again you have to be careful. First, always ask two people if you may join between them (“May I join here?”), because if you don’t you may be breaking in between a courting couple or between two old friends who haven’t seen each other in 10 years or things like that. Often if they don’t want you to join between them, they’ll let you in somewhere else. Second, never ever join between the leader and the second person in line. The second person in line is sort of the “back up leader” if the main leader decides to do some fancy show off steps that no one else will do and sometimes they are they are there to physically support the leader if the leader does big jumps or flips. Since this is all so culture dependent, it’s best to watch what others do before you join in or ask around what the local etiquette is. Again, at international folk dance clubs in the USA, you’re usually pretty safe joining in at the tail though.

3. Couple Dances

Dances that require two people (and only two people) to work together as team are called couple dances. These dances often have different roles for each member of the pair to play. Think of ballroom dancing, and you’ll know what I’m talking about. These dances are found all over western and northern Europe as well as in the places that Western Europeans conquered and colonized. These dances sometimes require a little interaction with other couple (e.g. to switch partners in a mixer), but for the most part, you’re mainly dancing with that one person. We distinguish couple dances from “set dances” where each couple has a lot of interaction with other couples. Set dances will be the focus of section 5. First, however, we’re going to look at the various ways couple dances are structured in terms of position on the dance floor, in terms of hand holds and the special skills that are required to work with a dance partner.

3.1. Gender Roles in Couple Dancing

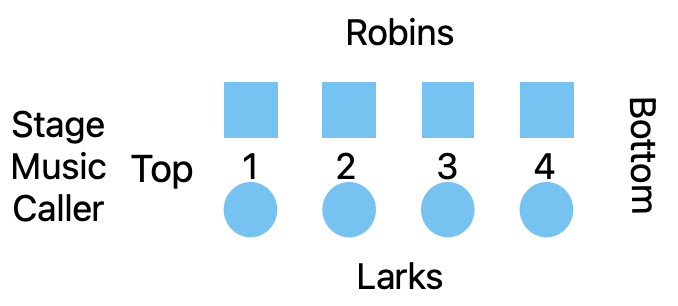

In order for couples to dance as a team, they often do slightly (or completely) different steps from each other. They may also have slightly different roles to play in moving as a couple around the dance floor. These roles, i.e., which set of footwork you use and who is the “boss” when it comes to steering the pair around were historically associated with traditional genders. Until very recently certain footwork was done only by men, who were also given the role of leaders who guided their partners around the room. Women were considered followers and typically did the opposite or complementary footwork to the men. There are of course oodles of problems with this traditional segregation of roles along sex or gender. Not only does it not recognize the complexity of people’s gender identity and associate stereotypical qualities to the genders (“men are leaders; women are followers”) and assign problematic power structures to the dance, it actually rarely reflected reality. People have been dancing a different role than their sex assigned at birth for hundreds of years. Keep in mind that men have been discouraged from dancing in the west for a long time. This has often meant that there were fewer men than women, so women have been dancing the men’s role with other women for a long time. It’s also the case that in LGBTQ+ communities throughout the world, even ones that were deeply suppressed and pushed underground, people danced either role. Tango in Argentina and Uruguay was danced by same-sex couples since at least the early 20th century. In the late 1800s western US, all male-communities of cowboys and miners did square and couple dances with men taking the “women’s” role. It’s also worth noting that in many social situations, women were actually the stronger dancers even in a mixed gender pair, so they had to actually lead the couple from the follower’s position. In the 1960s through the 1980s, LGBTQ+ communities started questioning the association of dance role with sex or gender. There is in fact, nothing inherently masculine about being the leader or feminine about being the follower. So, in these communities they looked for a new set of terminology to describe the different roles in couple and set dancing. A number of proposals have been put forward. Some groups use leader and follower. But this terminology isn’t fantastic for some styles of dancing (e.g., contra dancing), where the asymmetric relationship between the two positions/roles isn’t obviously one of leading and following. The most recent set of terms that has caught on in folk dance communities comes to us from contra dancing. In this terminology, the two roles are distinguished as larks and robins. Lark is the role that was traditionally associated with men and Robins with women. But with this terminology, people of any gender/sex can dance in any role as either a lark or a robin. The terms lark and robin are meant to be mnemonic. Larks are the leaders when that role has to be distinguished. In dances where you stand side by side with your partner, they stand on the left. In many dances where there is asymmetric footwork, the lark starts with the left foot. Robins by contrast, stand on the right when standing next to their partner. They also typically start with the right foot when the footwork is asymmetric. In the dance descriptions in this book, I will be using this new lark and robin terminology. What role you choose to dance is entirely up to you and is not necessarily tied to your gender or to your sex.

3.2. Dance Floor Formations

Couple dances are often done in completely random positions around the room. This is sometimes called scattered formation. Dancers can move around anywhere in the room, although by convention most motion still happens in a “line of direction”, which is typically counterclockwise.

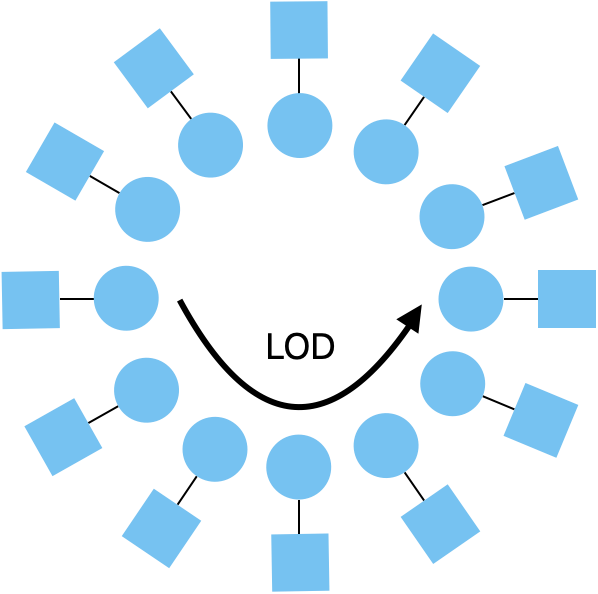

Another common position is to have couples arranged in a circle but with one person closer to the center than the other. Typically, this is done with the larks starting in the middle and the robins on the outside of the circle. They can dance in a wide variety of handholds and orientations, but frequently the couple both faces LOD (CCW), with the lark on the left and the robin on the right. In many groups, this formation is called spokes of a wheel, where each couple forms a spoke. This formation is often also called a double circle, especially if you face your partner (rather than facing LOD).

Also common is a closed circle of couples, with larks standing on the left and robins on the right and with everyone facing in and everyone holding hands with their partner and with their neighbor. Interestingly, when couple dances start in this formation, they often start by moving in RLOD (CW) first. No one is sure why.

3.3. Mixers

There is a special kind of circle couple dance called a mixer. The defining characteristic of mixers is that you switch partners each repeat of the dance. Mixer dances are choreographed so that at some you progress to a new partner. Typically, you progress so that you are dancing with one of your corners or neighbors.

3.4. Some Basic Partner Holds

There are a variety of handholds that are used in couple dances. It should be noted that I’m giving the terminology as it is used in folk dancing. The same terms might be used quite differently in other kinds of dance. In particular in Ballroom dancing there are some quite different definitions of the names I’m discussing here. Let’s start by discussing open or side-by-side holds, where you stand next to your partner and you both face the same direction.

The easiest of these is nearer hands. In this hand hold the lark gives their right hand to their partner and the robin takes it with their left hand. The hands can either be held up (like W position in circle dances) or down (like V position in circle dances). In the photo in figure 23.25, the robins/followers are all men and the larks/leaders are all women, the reverse of traditional gender roles, but this is just a coincidence.

A slightly more intricate handhold is the skaters’ position . Here again you stand side by side with your partner, both facing the same direction. Lark is on the left and robin is on the right. The lark extends their right hand in front of the robin’s stomach and the robin takes it with their right hand. The robin extends their left hand in front of the lark’s stomach and the lark takes it with their left hand. This is a little bit like a two-person version of a basket hold.

It’s also possible to do the equivalent to a back basket. Which is the rear skater’s position:

The next side-by-side position has two common names: varsouvienne position and shadow position. In this hold, the lark is on the left as usual. The robin raises both their hands up to shoulder height (or slightly higher) and the lark takes the robin’s right in their right behind the robin’s right and takes the robin’s left in their left in front. The term varsouvienne means “from Warsaw” in French. Its alternate name “shadow position” reflects the fact that the lark stands slightly behind the robin (but offset to her left) and thus the lark shadows the robin.

Low shadow position is one where the lark’s R hand is on the robin’s R waist. The robin’s R hand rests on top of the larks on the robin’s waist. The two dancers hold left hands in front of their bodies, low and often pointed slightly forward.

In sweetheart hold (also called cuddle position), the dancers are again side-by-side and the lark’s right hand is on the robin’s right hip. The robin reaches across their own body and grabs the lark’s right hand on the hip with their left hand. The robin also crosses their right hand across over their own stomach and takes the larks left hand.

Our final side-by-side position is sometimes known as promenade position or sometimes open ballroom hold . People often think that skater’s position is called a promenade hold because it is often used in the dance move called a “promenade”. Also, the term promenade hold is synonymous with skater’s position in the style of dancing called square dancing. But in folk dancing it usually has a clear meaning: The lark’s right hand rests on the robin’s right hip as in many of the other holds above. The robin’s left hand rests on the lark’s right shoulder. The free hands (lark’s left and robin’s right can be in a variety of positions. Often, they just hang down to the side, but they can also rest on the hips or if the person is wearing a skirt, they can hold the skirt and swish it back and forth.

Next, we turn to closed positions, where the partners are face-to-face or are facing opposite directions. The simplest such hold has the dancers face-to-face and the lark holds the robin’s right in their left and holds the robin’s left hand in their right. This is called a two-hand hold. It is often used for turning around or circling with your partner or for sashaying from side to side.

A derivative position from the two hand hold is the yoke position. Starting in the two hand hold position, each partner makes a 1/4 CCW turn (to the left) so that they are right hip to right hip. Simultaneously, the dancers raise both hands (still held) up and drop their left hands (and their partner’s right hand) behind their own head.

Another very common closed position is (closed) ballroom position. Be careful about this term because in folk dancing this hand hold is slightly different stylistically than the way it is used in ballroom dancing itself. In this hold, the dancers stand face to face. The lark’s right hand rests on the robin’s left shoulder blade. The robin’s left hand lies on top of the lark’s right arm and their left hand rests on the lark’s right should. The lark holds their left hand up to their left side forming a little V with their thumb separated from their other fingers. The robin rests their right hand in the V formed by the lark’s left hand.

Instead of facing immediately face to face, a variation on the ballroom hold has exactly the same hand and arm configuration, but you stand right hip to right hip, essentially side by side facing opposite directions. This is called the offset ballroom position or side-by-side ballroom. This position can be used where one partner walks forward and the other walks backwards. It is also the position used for traditional partner swing, where the couple turn around each other pivoting in place.

There is a gender balanced version of this offset position that can also be used for swings (gender-neutral swing position). The lark’s right hand and robin’s left are just the same as in the offset ballroom position. The robin’s right is on the lark’s shoulder blade and the lark’s left rests on the robin’s shoulder.

Another ballroom-hold-related position is the semi-open ballroom position or tango-walk position. The hand hold is identical to closed ballroom position, but instead of facing each other you are side-by-side facing the lark’s left and the robin’s right hand.

There are a few other positions where the partners face each other and stand close but are not in ballroom position. These holds are particularly useful in dances with fast pivoting motions and are commonly found in Scandinavian dances. In shoulder/shoulder blade hold, the lark places their hands on the robin’s shoulder blades and the robin rests both their hands on the lark’s shoulders (or sometimes on their biceps). Shoulder/waist hold is extremely similar except the lark puts both their hands on the robin’s waist. These holds can be done directly face to face or they can be offset like offset ballroom position.

Dancers can also hold crossed hands when facing each other. This is a little bit like the skater’s position or the front basket hold except facing. The lark and robin face each other. The dancers hold right hand in right hand and left hand in left. Usually (although not always), the right hands are on top of the left.

With some variations, you can also swing in a crossed position. For example, in Scottish country dancing, everyone holds their partner’s right elbow in your right hand standing slightly offset from each other and then hold hands under the joined rights in a handshake hold.

Need new picture

Figure 23.41: Cross hand swing position

The next two positions are derivative from the crossed hand position. That is, they all start in crossed position and then you do an additional movement to get into these holds. These holds are really rare, but they are found in both Cajun dancing from the southern USA and in German and Austrian dances. First, we have the little window hold. It starts in the cross handed hold. You raise both hands up without letting go of either. The robin then turns 1 and 3/4 around CW, while the lark just turns 1/4 CCW. You end with your right elbow touching your partner’s shoulder with the upper arm parallel to the floor. The right arms are bent and the hands are held up above the bicep, thus forming “the little window”. The left hands are still held, but they are connected through the window and rest on the right bicep. You can find a video of getting into this position linked in Chapter 25.

The big window hold is very similar, it starts the same way, except after the robin has made one complete CW rotation, the couple lower the joined right hands down to waist level, without letting go. The robin keeps turning 3/4 and the lark makes a 1/4 turn CCW, you end with joined R hands behind the robin’s back and the joined left hands forming an arch (the big window) above the couple’s heads.

Need new picture

Figure 23.43: Big Windows

3.5. Good Partnering Skills

Dancing with a partner is an exercise in teamwork. Couple dances don’t really work unless both dancers are doing their part. Although in many dances the lark is the leader, the robin plays an equally important role. The key to good partnering is using your bodies to communicate with each other and give each other information about your movement around the room and your movement with each other. A lot of this communication happens through the hand hold. A subtle push with the left hand can indicate that the couple will rotate CW or to move forward in the line of direction, or a pull of the right hand can indicate moving towards RLOD etc. This isn’t just the leader/lark’s responsibility. The lark can only see half the room at any given time. The robin can also give physical cues to their partner. When a couple has good kinesthetic communication the feel and flow of the dance can be magical.

Needless to say, it’s important for both dancers to pay attention to where they’re going. You don’t want to injure yourself, your partner, or any other couples on the floor with a collision. Finding the right space to dance in, especially when the dance floor is crowded is the responsibility of both dancers. When you’re moving quickly or spinning around this can be challenging, and a lot of dancers can get dizzy, especially followers. There are several techniques for avoiding getting dizzy. One is to “Spot”, that’s the technique of choosing some fixed thing in the room to stare at during each rotation of the couple, another is to focus on a button or piece of jewelry your partner is wearing, but in either case you’re still responsible for avoiding crashes and hurting someone.

You’ll often hear experienced dancers talk about giving weight. This does not mean dropping all your weight into your partner’s arms, that’s dangerous! It’s about pulling just far enough away from your partner that they can sense your body cues. One easy way to feel this effect is to get into one of the facing couple handholds above, like ballroom position and slightly “sit” down. Don’t lean back, don’t lean forward just sit enough back that you can sense your partner through your hands. There’s nothing worse than trying to do a couple dance with someone who won’t give weight. It’s like trying to dance with a wet paper bag. The concept of giving weight does two things: (1) Most importantly it helps in the above mentioned communication you can feel the cues your partner is giving you. (2) In dances where the couple turns fast around the room or swings in place, giving weight is what gives you the momentum and control the turns effectively. Reading about giving weight isn’t particularly helpful, so I encourage you to find an experienced dancer who can show you, so you can feel it in your body.

3.6. Couple Dance and Mixer Etiquette

In the movies, there is a trope of “cutting in” where you steal away a potential romantic partner from a rival by asking to “cut in” and take their place. This never happens in folk dancing! But it should hint at the fact that there is a complex etiquette around couple and mixer dances.

First, like circle dancers you should always ask permission to dance with someone, and you should never take offense if they say “no”. There could be a number of reasons they might say no, perhaps they promised to dance with someone else or perhaps they are too tired to dance this one. If someone says “no” just thank them and move on.

During the dance, pay attention to your partner and their comfort. Are they having fun? Are they in pain or discomfort? Similarly, if you are in discomfort or you feel like you’re moving too fast and your partner isn’t responding, it is perfectly acceptable to just tell your partner to please slow down or to hold you a different way.

At the end of dance, always thank your partner for the dance. It’s also considered polite to clap at the end of a dance. If you were dancing to live music you’re applauding the musicians, but even if you’re dancing to recorded music clapping indicates your appreciation for your partner and all the other dancers around you who have made the dance a success.

Mixer dances have their own special rules that happen as you’re switching partners. If for some reason, the progression goes wrong and you don’t immediately get a partner, you should never just leave the dance floor. That’s because if you don’t have a partner, there will almost always be someone else without a partner! If you drop out, you’re forcing them to drop out too. If you don’t get a new partner in a mixer dance, the correct solution is to head to the middle of the circle (or dance floor) and raise your hand. We call this lost and found is in the middle. Inevitably someone else who is missing a partner will come and find you and then you can rejoin the dance.

4. Trio Dances

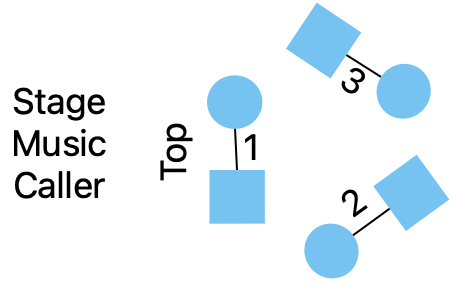

Trio dances are like couple dances, but with three people instead of two. Traditionally, these were done with one man standing between two women (or more rarely one woman standing between two men), but nowadays you can do them with any combination of dancers. We have non-gendered terminology here too. Often, these dances are done with the three dancers in lines forming spokes of a wheel facing the LOD. The dancer closest to the middle of the circle, on the left of the line of three, is the lark. The dancer on the outside of the circle is the robin and the one between them is called the center (or if you want to keep with the bird, names you can call them the cuckoo).

On rare occasions trio dances can be done as mixers. When this happens the center dancer progresses to a new trio in one direction (usually forward in LOD) and the lark and the robin both progress together in other direction (typically RLOD) as a team to join up with a new center dancer.

5. Set Dances

5.1. Set dance configurations

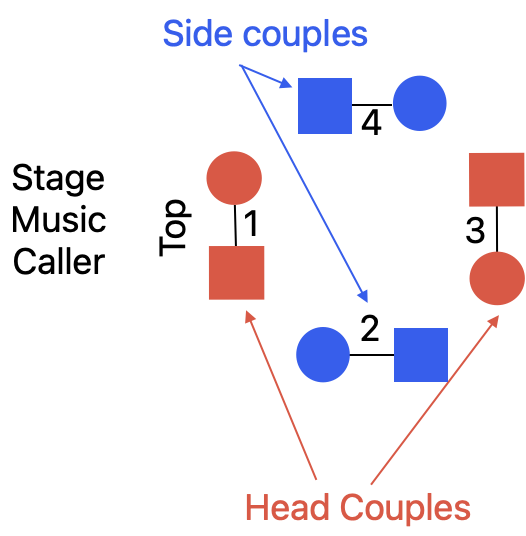

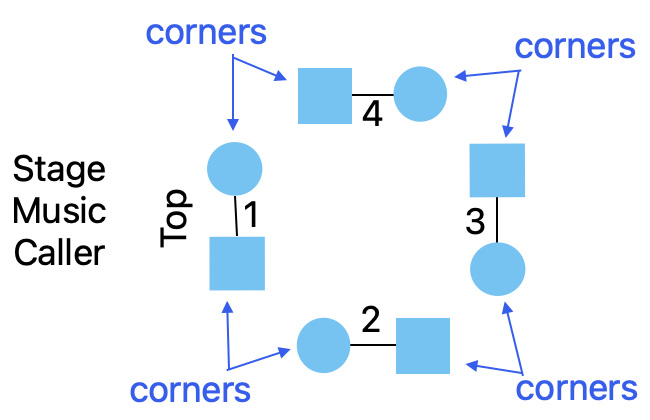

A set dance is a dance where couples interact with other couples by completing short figures or patterns on the floor. The kind of set dance that most people will be familiar with is a square dance. Square dances are, like their name implies, done by four couples arranged into a square. In some countries squares are known as quadrilles. When completing the figures of a dance each couple has a different role to play, so we have names for each of the couples. The first couple (often abbreviated 1C) is the couple with their backs to the band, music, dance caller/teacher or stage. The couple on their right is the second couple (2C); the couple opposite them is the third couple (3C) and the couple to their left is the fourth couple (4C). Couples 1 and 3 are known collectively as the head couples. Couples 2 and 4 are known as the side couples.

In addition to your partner, there is another person you are likely to do a lot of dancing with. This person is your neighbor (the person of the other gender role), who is standing next to you but is not your partner. In squares this person is called your corner. In the diagram below, lark #1’s corner is robin #4. And robin #1’s corner is lark #2. The term corner has different meanings in other forms of set dancing as discussed below.

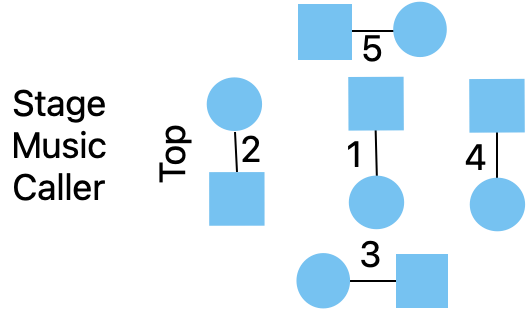

There is a rare form of square where there are 5 couples. The extra couple in the center is the first couple, and they face the top. This extra couple is sometimes known as the lead couple. All the other couples are renumbered accordingly.

Another variant of the square is done with three couples arranged in a triangle. If necessary, these are numbered with the couple whose back is to the music as couple 1; the couple to their right as couple 2 and the couple to their left as couple 3.

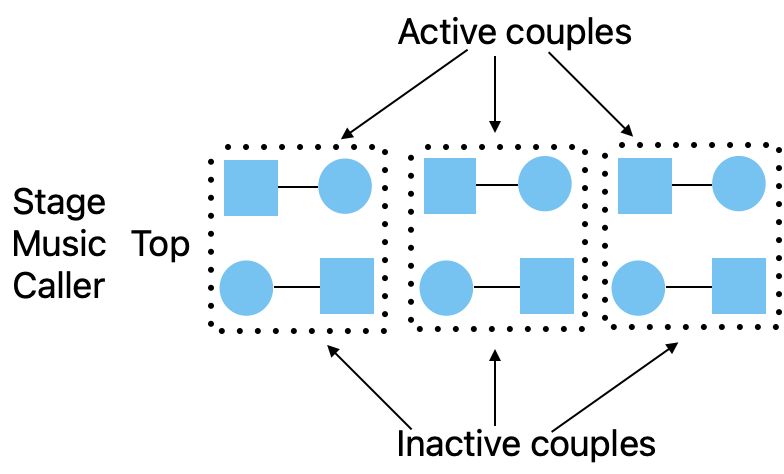

A totally different set formation is actually much more common in the dances of Europe. This is the formation known as a longwise sets or contra lines. In this configuration, you have couples arranged in a long line of couples. Each person faces their partner across the set, as such they are “contra” or against their partner rather than standing side by side. In different dances, the number of couples in each set can vary. One common configuration is the four couple set and another is the three couple set. In these configurations, the couple closest to the music/stage/caller is the first couple, the next one is the second, and so on. The first couple is at the top of the set and the couple at the opposite end is at the bottom of the set.

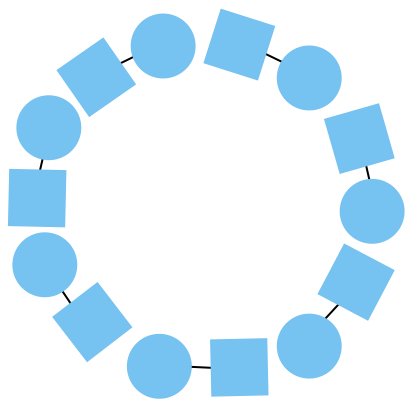

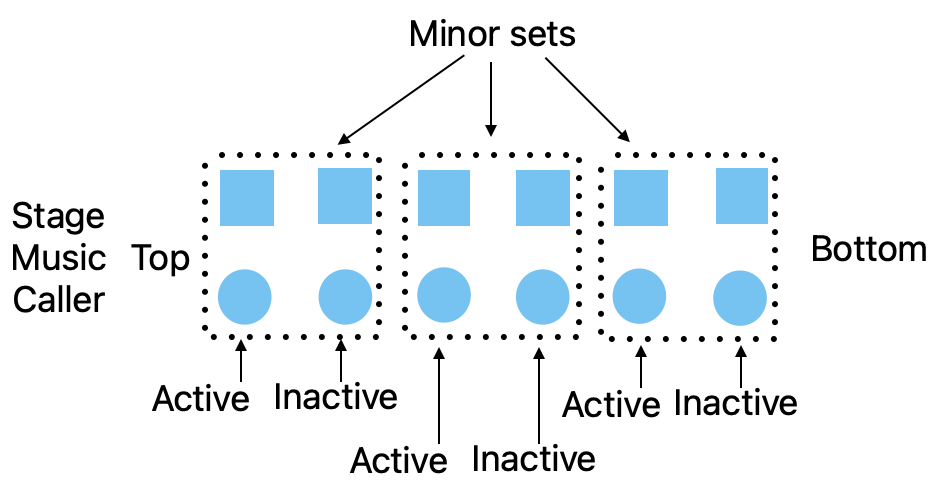

Another common configuration is to do the longwise set for as many as will. This is particularly common in American contra dancing. In this configuration, the set can have as many couples as can fit comfortably in the space. When you have a as-many-as-will dance, the long set is divided up into minor sets within the long set. Most often these minor sets consist of two couples, which is called duple (or double) minor. You will find the occasional dance where you have triple minor sets, or minor sets consisting of three couples. When you have a line of duple minor sets, each time through the dance you dance with a new couple. In each of the duple minor sets, the couple nearest the music is known as the active couple and the other couple is known as the inactive. During the choreography of the dance, the couples will progress to meet a new couple. Active couples progress down the set (i.e., towards the bottom) and inactive couples progress up the set (i.e., towards the top). This is also true in three and four couple set dances. Typically speaking you are an active couple who progresses couple-by-couple down the set until you reach the bottom, or you are an inactive couple who progresses up the set with each active couple until you reach the top. Once you reach the top or the bottom you sit out one turn and then you switch roles – actives become inactives and inactives become actives – and work your way in the opposite direction up and down the set.

Within longwise sets there’s a few variations on starting position. The first configuration is known as proper. In proper dances all the dances of the same gender role stand on the same side of the set. In proper formation, if you have everyone look up the set towards the musicians/caller/stage, then the larks are all in a single file line on the left and the robins are all in a single file line on the right (i.e., when facing their partners, all the larks have their left shoulder towards the music and all the robins have their right shoulder to the music.) Proper formation is the oldest of the longwise set formations. The term improper refers to a configuration where the actives in each set are “crossed over”. So, the lines on the sides alternate lark-robin-lark-robin etc.

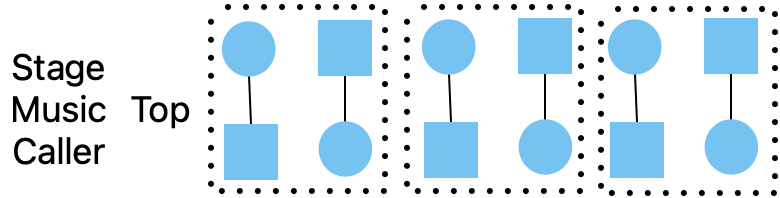

There is an advanced style of longwise set called becket formation. In this configuration instead of standing across the set from your partner you stand next to your partner on the same side. Progression in becket formation move down the side (so everyone on the right side progresses down and everyone on the left side progresses up).

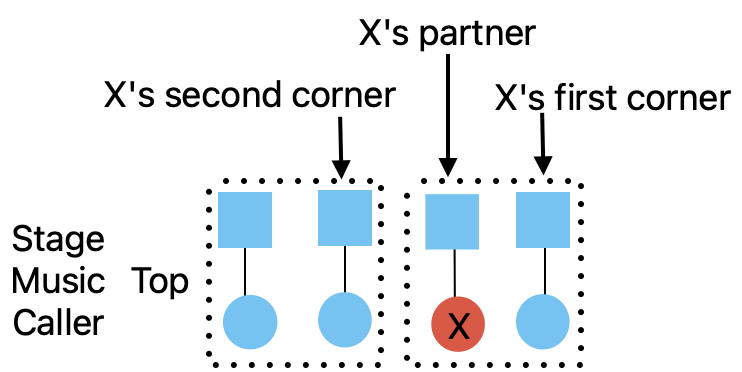

In longwise sets, the term corner has a different meaning from that of square dancing and it depends upon whether the dance is proper or improper. In a proper longwise formation, in English dancing and in Scottish Country Dancing, you have two corners. If you look across the set at your partner and look to the person standing to their right (from your perspective), this person — on your right diagonal — is your first corner. It you took to the person on the other side of your partner (i.e., on your left diagonal) is your second corner.

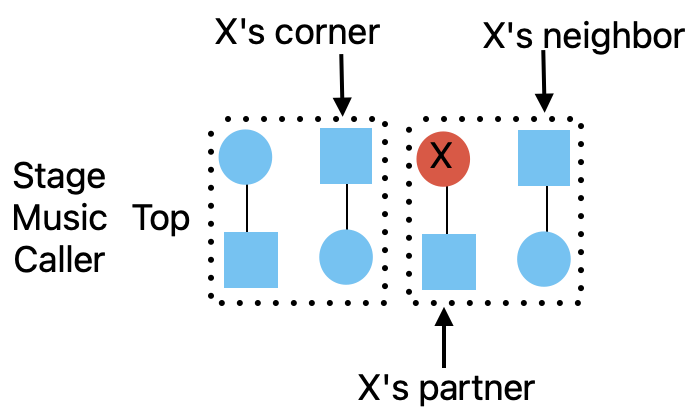

Things are different in an improper contra. Within your minor set of two couples, your neighbor is the person of the other gender role, who is not your partner. Your corner is actually the person standing immediately behind you, who is neither your partner nor your neighbor. They are actually dancing in the adjacent minor set, but you still might interact with them depending upon the choreography.

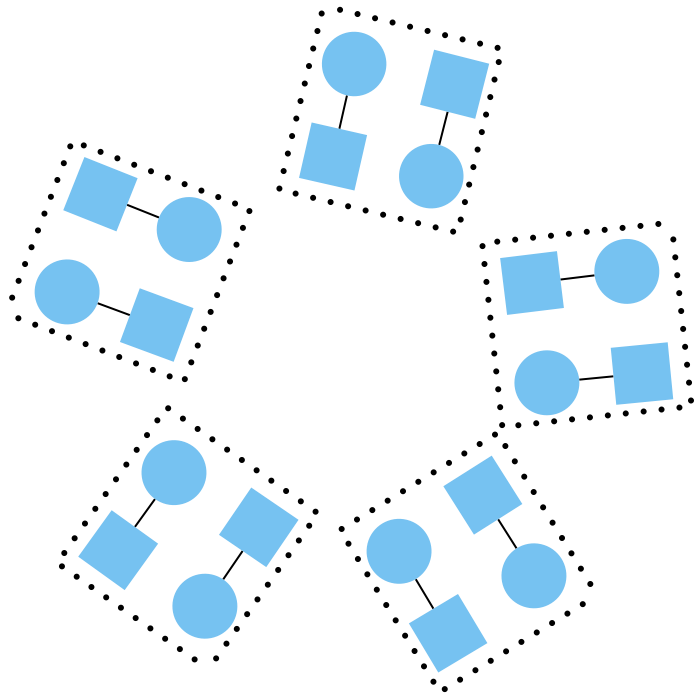

One common variation on an as-many-as-will longwise set the improper minor sets organized in a big circle around the room. In effect, it’s like the spokes of a wheel configuration in couple dances, except you have couples facing couples. This configuration is known variously as a Sicilian circle or a Circassian circle.

As our last configuration, we can also have Sicilian circles with trios facing trios.

5.2. Set dance etiquette

Some of the etiquette of dancing in couple dances transfers over to set dancing too. You always ask someone to dance, and you never take offense if they refuse. You also thank your partner after the dance and walk them off the floor. Like in couple dances, you have to be aware of your own physicality and that of your partner and make sure they are comfortable and feel safe. The trick to doing set dances is these basic courtesies also have to extend to all the other dancers in your set. Be aware of where the other dancers are and are going; be careful in turns and swings with other dancers, etc. It is commonly agreed that you should also thank your entire set after the dance. You also always clap at the end of the dance for the musicians and teacher/caller and to acknowledge the contributions of your set mates. Depending upon the particular style of set dance you may also be expected to acknowledge your partner at the beginning of the dance often this is by a nod of the head, a bow, or a curtsey. Sometimes there is a little extra bit of music at the beginning of the dance for this acknowledgment or sometimes there is a special chord played.

Since dancing in a set is a team sport, it’s pretty important that you either know the dance before you start, or at the very least you are good at listening to the directions of the caller or the teacher during the dance. It is not unusual to end up in a set with someone who gets lost or is going the wrong way and that can really mess things up. In such circumstances there is an etiquette to helping that lost dancer discretely, without embarrassing them and without undermining the teacher or caller, who undoubtedly is also trying to help them. Don’t talk over the teacher or caller or try to teach from within the set. You can help the lost dancer by giving them clear non-verbal cues. For example, if they don’t know what direction to go you can point in the direction they should be going with your head or your finger. If they should be swinging or turning you, you can say “over here”, but don’t drown out the caller. One very important thing is that you should never grab or push someone even if they are going the wrong way or are in your way. Usually a smile, a wave or offering your hand to guide them will suffice.

6. Conclusion

In this chapter, we’ve looked at the most common configurations and dance holds used in the folk dances of Europe and the Middle East. We looked how set dances are organized, how you dance with a partner, how circle and open circle dances are arranged, and even at how solo folk dancing works. This is a lot to take in, and very hard to understand without actually doing the dances. I intend these appendices to be primarily reference works that you can come back to and look at if you need some specific directions.

Further Reading and Web Resources

- https://www.ndca.org/pdf/Holds%20and%20Positions.pdf

- https://www.scottish-country-dancing-dictionary.com/hand-positions.html

- https://www.scottish-country-dancing-dictionary.com/types-of-sets.html

- https://www.scottish-country-dancing-dictionary.com/set-structure.html

- https://www.ibiblio.org/contradance/thecallersbox/Glossary.htm

- https://round.soc.srcf.net/dances/elements

- https://socalfolkdance.org/resources/couple_dance_positions.htm

- https://socalfolkdance.org/resources/chain_dance_positions.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_country_dance_terms

- https://www.cincinnaticontradance.org/contraterms.htm

- https://www.cdss.org/elibrary/dart/appendix_a.htm

Discussion Questions

Discussion Question 1

Folk dancing, as defined in chapter 1, is meant to be largely a social or community activity. How do the various dance formations further or impede these aims? Do handholds and formations matter when it comes to the purposes of building social bonds through a fun activity?

Discussion Question 2

Sometimes you end up dancing next to or with someone who is physically quite different than you. They might be much smaller or much larger than you and this makes certain handholds uncomfortable or even impossible to do. For example, your textbook author is quite tall and if I stand next to someone considerably shorter than me, then shoulder hold in circle dances is extremely uncomfortable for both of us. How would you go about dealing with a situation like that while still being polite and helping everyone to have a good time?

Discussion Question 3

In North American culture, physical touch between two people is often limited to people in an intimate relationship or a parent-child relationship. While you might hug a friend, and shake hands with a new acquaintance, it is largely considered taboo to touch people you are not close with. In folk dancing, you have to hold hands with strangers for long periods. You might also be asked to hold them close to you when doing couple or mixer dances. You will likely be in their personal space in ways you would not normally do in other contexts. This can be very awkward for beginners. First, did you experience this awkwardness? How did you deal with it? Second, how might folk dance teachers and leader help new folk dancers deal with these feelings and provide a safe environment that everyone can enjoy.

Media Attributions

- Figure 23.1: Four-wall dance configuration © Andrew Carnie

- Figure 23.2: Short line © Andrew Carnie

- Figure 23.3: Open circle © Andrew Carnie

- Figure 23.4: A closed circle © Andrew Carnie

- Figure 23.5: V hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.6: W hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.7: W hold, detail © Andrew Carnie with Shala Folk Dancers

- Figure 23.8: Pinky finger detail © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.9: Y hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.10: Black Sea hand detail © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.11: T hold/Shoulder hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.12: Escort Hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.13: Greek Escort Hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.14: “GluGlu” from the front © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.15: “GluGlu” from the back © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.16: Kurdish hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.17: Interdigitation © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.18: Front basket © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.19: Belt hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.20: Back Basket from the front © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.21: Back Basket from the rear © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors

- Figure 23.22: Line of Direction © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.23: Spokes of a wheel formation. Circle = lark, Square = robin © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.24. Closed circle of couples © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.25: Nearer hands joined © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.26: Skater’s position. © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.27: Rear Skater’s Position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.28: Varsouvienne position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.29: Low shadow position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.30: Sweetheart position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.31: Promenade position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.32: Two hand hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.33: Yoke position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.33: Closed ballroom © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.34: Lark’s L hand and robin’s R hand in ballroom hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.35: Off set (hip to hip) ballroom © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.36: Gender-neutral swing position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.37: Semi-open ballroom or tango-walk position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.38: Shoulder/shoulder blade hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.39: Shoulder/waist hold © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.40: Crossed hand position © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.42: Little windows © Andrew Carnie with DNC179A preceptors is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.44: Trio formation is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.45: Trios as spokes of a wheel © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.46: A square set © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.48: The position of corners in a square © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.49: 5 couple square © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.50: Triangle formation is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.51: Four couple longwise set © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.52: Longwise set for as many as will, proper duple minor sets. Larks are circles, robins are squares. © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

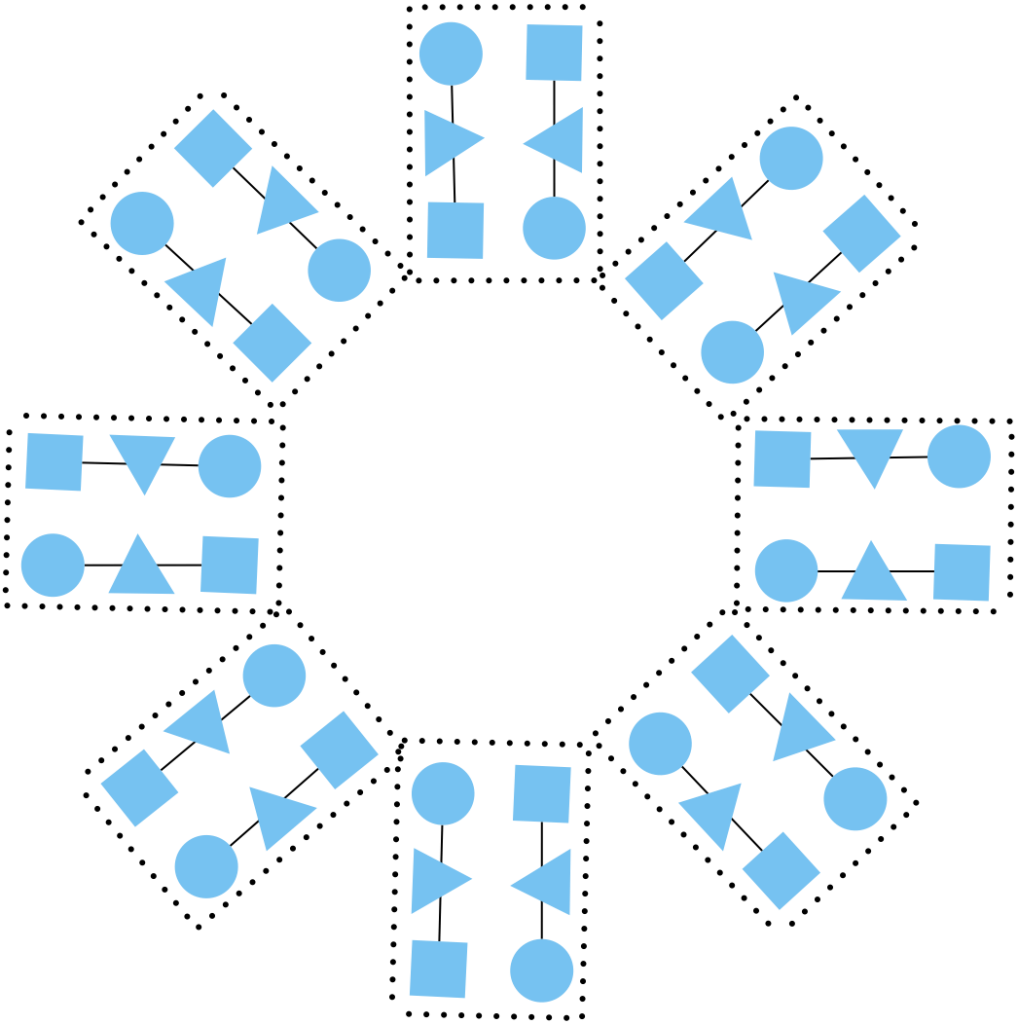

- Figure 23.53: Longwise set for as many as well with improper duple minor sets marked with dotted boxes. Larks are circles. Robins are squares. © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.54: Becket formation © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.55: X’s 1st and 2nd corners. © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.56: X’s partner, corner and neighbor. Improper set. © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.57: Sicilian Circle or Circassian Circle formation © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license

- Figure 23.58: Sicilian circle of trios © Andrew Carnie is licensed under a CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike) license