6 Activism

Before the internet was an effective product marketing tool, it was a tool of activism – and social media has extended and complicated the ways activists can use it (in other words, its activist affordances). This chapter takes a few key movements as examples – from 1994 when Mexico’s Zapatista movement forced the Mexican government into a ceasefire, to 2017 when Black Lives Matter hashtags now quickly activate publics in the US and beyond. I refer to these movements under the umbrella of creative online activism. What ties these movements together is their creativity in using the affordances of the internet to promote activist agendas and avoid the pitfalls of oversimplification and appropriation.

Note: This chapter focuses on movements that have coalesced (formed) around racial and ethnic identity groups, as well as income inequality and political decisions.

The Zapatistas

In early 1994, only a tiny percentage of the world was online, and the term “social media” did not exist. The internet was very young and very Web 1.0, with static pages that did not allow visitors to contribute. (You can review Web 1.0 vs Web 2.0 in Chapter 2). Yet our first example of creative online activism begins here, with Mexico’s Zapatistas. Creative deployment of the affordances of a young, sparse internet both saved indigenous protesters in Chiapas, Mexico from slaughter and allowed them to influence the new global economy.

The beginning of the story was the end of life as many in rural Mexico knew it. Governments of the US, Canada, and Mexico began negotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in the early 1990s, forging interdependence between their economies. Among other deals, this trade agreement would subsidize corporations taking over Mexican land to grow cheap crops. Many Mexicans – particularly the native, or indigenous, people – foresaw that this would lead to drastic alteration of the land and to farming by genetic crop modification and spraying of chemical pesticides.

As their political leaders worked toward NAFTA, Mexican farmers fought it using traditional methods. In the early 1990s, protestors staged in-person demonstrations at the zocalo (town square) in Mexico City. And they organized and wrote impassioned statements in print media about the devastating consequences NAFTA would have on farming and many other aspects of life in their country. But North American governments ignored these offline pleas and signed NAFTA into effect in 1992 and 1993.

On January 1st, 1994, NAFTA became the law of the land in the US, Mexico, and Canada – and the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) rose up against the Mexican Government under the leadership of a masked man known as Subcomandante (Subcommander) Marcos. This army of “Zapatistas” – an army of mostly poor, rural, indigenous people inspired by the historic Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata – peacefully occupied the city of San Cristóbal de las Casas in the state of Chiapas, to demand that their protests against NAFTA be seen and heard. Rising up against the Mexican government seemed like a catastrophic move by the EZLN occupiers, many of whom were poor indigenous farmers from the Chiapas area.

The Mexican government was enthusiastic about NAFTA, as they would benefit financially from corporate NAFTA investment even if their farmers suffered. So it seemed certain the formidable Mexican army would covertly slaughter the small EZLN forces before their protest could make Mexico look bad as corporate investment. But ironically, in this case the internet was what Martinez-Torres describes as Janus faced, helping governments repress people while helping those people protest that repression at the same time. While young, online global networks made it possible for economies to globalize and to crush poor people in the process, they also made it possible to mobilize networks of popular protest and fight back.

Enter information warfare

When on-the-ground resistance alone got the Zapatistas little traction in their resistance to NAFTA, they turned to the internet and began a campaign of information warfare – the strategic use of information and its anticipated effects on receivers to influence the power dynamics in a conflict. Thanks to the affordances of the early internet to connect people in similar struggles in different places, international peace activists were already networked online in the mid-1990s; the Internet Archive has lists and snapshots of pages describing some of these organizations. Some of these activist organizations were witnessing or supporting similar struggles in other countries, as poor people battled transnational trade agreements that would destroy their ways of life.

The EZLN Army got the international word out about their cause with remarkable speed, thanks to these online peace networks. With the charismatic masked leader Subcommandante Marcos as a spokesperson, the EZLN Zapatistas created a dramatic campaign online. Their vivid imagery of the EZLN’s masked army of farmers spread rapidly across international online networks.

At the height of their online visibility, twelve days after declaring war on the Mexican Government, the Zapatistas publicly called for a ceasefire. The Mexican government still had the physical power to annihilate EZLN – but now the world was watching. Once EZLN called for peace, any action against their forces including women and children would make Mexico look evil – and risky as a corporate investment destination. As a result, the Mexican government was forced to accept the EZLN ceasefire. They could not reverse NAFTA; it would take more than an awareness campaign to reverse such a powerfully backed agreement. But the EZLN protesters lived and continued their demands for social change.

The EZLN’s Information War has inspired many civil society movements visible today. These include current movements against genetically modified food and for “fair trade” compensation of farmers. In terms of online strategies, the Zapatistas’ activist campaign was an early example for activists of how media can be used sociopolitically to demand civil rights – and to recognize how, Janus-faced, those same media can also work against those rights.

In the next sections, I demonstrate how the Zapatistas’ strategies fall under the umbrella of creative online activism and why such strategies remain powerful.

Creative online activism in recent times

Political campaigning in the 21st century

Student Contribution, Fall 2020

Music: Automaton en Avant by Scanglobe, CC-BY -NC.

The Accessibility of Politics on Social Media

One of the main features I enjoy about social media is the level of accessibility it provides. In one tap, you can connect with an old friend, find entertainment, get news and so much more. One “old school’ medium that has found new life on social media is politics. The accessibility of politics via social media has made politicians and issues easily available to the general public thanks to their integration of the new media into campaigns.

Tana Mongeau is a twenty-two-year-old influencer who gained a lot of followers from her Youtube “storytime” videos. She tries to be as transparent as possible with her audience and is not afraid to be herself. Mongeau has over 5 million Youtube subscribers which means that a lot of people value her opinions. I have watched Tana Mongeau’s Youtube videos before and I always admired how authentic she was with her audience. Tana usually tries to stay out of controversial situations because she has gotten herself into trouble in the past on social media leading to her almost being canceled. This is why I was a little surprised to see her actually campaigning which usually means half the people in your audience will disagree with you. I do not look into politics on social media because I never know if there is misinformation from an unreliable source. I will also see a lot of disinformation where people will intentionally spread fake news to make one politician look better than the other.

Because social media allows for everyone to have a voice, there is a lot of that gets spread around by people who do not actually care about politics, but rather the attention. When I first saw “Booty For Biden”, I thought that it was probably just a meme trying to get Biden’s name out. However, Tana was very passionate about campaigning for Biden and said that it was true. This campaign strategy has proven to be successful with “naked philanthropists” such as Kaylen Ward who fundraised over 1 million dollars for Australia during their fire crisis. They tend to reward people who donate, or in this case vote, with a naked picture of themselves.

However, once again, Tana got a lot of backlash about her Biden endorsement campaign. Lots of people noticed that what she is doing can be considered “vote-buying” which is an electoral crime. Vote buying is defined as, “when offering an expenditure to any person, either to vote or withhold his vote or to vote for or against a candidate.” Punishments can include fines and up to two years in prison. It is also illegal to take a picture of your ballot in sixteen states and potentially criminal in another thirteen states. In light of this knowledge, Tana decided to change her requirements. Instead of sending her a photo of your ballot, you could just send her a video saying that you voted for Biden. With these lower demands, it is hard to account for how many people truthfully sent her proof, but Mongeau claims that she got “tens of thousands” of people to say they are voting for Biden.

Tana’s campaign ended up costing her some Youtube subscribers. She lost twenty thousand subscribers in September, which was around the start of her “Booty For Biden” campaign. Even though her channel took a hit, I believe her passionate dedication to the Biden campaign is admirable even if she may have lost some followers. In the end, she was able to use her platform to shine a light on a topic she was passionate about, which may have even swung some votes and led to Biden’s victory. Having her political view accessible to social media allowed for her to be even more transparent with her audience as well as earn herself some credibility by addressing a newsworthy national topic. “Booty For Biden” generated a lot of attention for the Biden campaign. Whether someone was pro-Biden or not, they were engaged in the political process albeit in a somewhat roundabout way. Perhaps that led to people finding more information on politics, even though it may have simply stemmed from wanting to see a nude pic.

About the Author

Jessica Nickerson is a sophomore at the University of Arizona studying Pre-Business. She enjoys spending time with her hedgehog and going on long drives. Jessica has been active on social media ever since 2011.

Respond to this case study…

What strategies made Tana’s campaign uniquely suited to social media, as opposed to traditional electoral media like newspaper advertisements, television commercials, and campaign mailers? Describe another political messaging campaign or endorsement that grabbed your attention in recent years. Describe the platform(s) involved, the technological affordances, and how your various publics responded.

Organizers have continued using the internet to mobilize, and their work has arguably been made easier with the development of mobile phone apps and social media. This timeline by Mashable gives a selective overview of noted online activist movements through 2011.

Creative online activism has developed in conjunction with social media apps since the mid-2000s. These apps are certainly not created equal when it comes to facilitating activism; in fact, some have been found to intentionally hinder the exposure of social injustice. For example, although they have had a huge user base for the last decade, Facebook algorithms have been found to hide or slow controversial and “negative” stories from its users’ feeds, making it a poor platform for activism.

But the platform is only a small part of the recipe for an activist movement. Human creativity has facilitated the use of technologies in activism in ways software developers never imagined. In a typical example of human shaping of technology, Twitter leadership didn’t build hashtags into the platform intentionally and even rejected the idea that they would be widely used; human users proved them wrong. Several years later, Twitter hashtags began playing important roles in online activism, including in the Arab Spring protests.

Case study: #settleforbiden

Student Content, Fall 2020

About the Author

Lilly is a first-year student at the University of Arizona who enjoys traveling and having a good time.

Respond to this case study…In her audio piece, this author focuses on the use of the hashtag #settleforbiden. In what ways could this hashtag fall under the category of creative online activism? In what ways could it be considered slacktivism?

Social media platforms like Twitter are sometimes practically credited with creating movements, but this technological determinism fails to recognize how much complex human wrangling is required to run an online campaign and keep control of its message. Only a small percentage of protestors used Twitter to exchange key information and then disseminated that information through face-to-face communication and other media. All messages that spread widely online face the threat of oversimplification and appropriation; only the best-executed retain their depth and complexity. And, regardless of platform, the real work for social change still happens across various digital and analog (non-digital) platforms – and most crucially, on the ground.

The Black Lives Matter Movement

One of the most well-known online movements to date is Black Lives Matter. The central phrase and hashtag of this movement came from Alicia Garza and Patrisse Marie Cullors-Brignac in July 2013 in response to the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the killing of 12-year-old Trayvon Martin. Armed with this concise phrase – and fueled by outrage over injustices against black citizens by American institutions including law enforcement today – Black Lives Matter has built into a sophisticated movement online and offline with profound influence on government policy and popular consciousness.

Although its signature phrase began online, the Black Lives Matter movement gained traction over the next year as Twitter users deployed #blacklivesmatter to mobilize on the ground. Subsequent hashtags used in connection with #blacklivesmatter networked protestors and helped them assemble massive on-the-ground demonstrations very quickly after subsequent police killings. These included #ferguson to organize protests in Ferguson, Missouri after police were acquitted in the killing of Michael Brown there in November 2014.

socially aware branding

Student Contribution, Fall 2020

Project 3

I chose the public of The Mayfair Group because it is an account that I am very familiar with and have been following for a long time. I think the content they create and post is incredibly inspiring and relatable to all. Their profile is very unique and full of creativity. It is a newly founded company and does a great job of reflecting some of the younger generations’ ideas. The Mayfair Group specializes in the sectors of public relations, social media, sales, graphic design, branding, events, and creative content. Their Instagram account inspires me to think out of the box, reflect on my life, and to be more original.

The Mayfair Group’s Instagram account affords exposure because it draws matters society guards as private into the public sphere. For example, they post very honest quotes about deeper emotions and the sides of life people do not normally portray. They feature real-life issues such as climate change, mental health, politics, and female empowerment. The brand specifically focuses on gender equality. They provide very positive content, especially things that improve your mental health. It is evolving and revolutionizing as a company and has grown immensely. With a following of over 400k on Instagram, The Mayfair Group has a great deal of influence. Their posts receive a lot of comments from people sharing their own thoughts and beliefs about the topics being discussed. It goes beyond their platform as they plan collaborations, events, social and PR campaigns for specific brands to give them exposure.

The account brings a lot of people from many backgrounds together to fight for one cause. This is a great example of an organizational layer. Modern activist movements are often ignited through interactions between key personalities, and networked groups of people who respond together. On posts discussing activism topics, the comment section is flooded with users who all share the same belief.

The Mayfair Group also is a fashion company and many of their products reflect these strong positive quotes and movements. This will bring a greater exposure because as the products and garments are worn, others who are not involved in the public will see it and possibly look into the brand. I am also especially interested in this brand and their public because it relates very well to my current major. I am majoring in marketing and I am extremely passionate about fashion, and the entertainment industry as a whole. The modern feel of this company is something I hold very high and hopefully will be able to work for a brand similar to The Mayfair Group. I pay close attention to the way they market their products and their choices of posts because everything is connected. I find it incredible that they have never paid for ads, followers, or promotions. This a very successful marketing story and I can learn a lot from this brand. The CEO says, “It all comes down to hustle and building relationships – that’s how a business should be built”.

About the Author

Created by a student for iVoices Media Lab.

Respond to this case study…

Describe some of the affordances of Instagram that have contributed to the Mayfair Group’s success. Are the strategies identified above unique to the public (or community) that follows the Mayfair Group? Use core concepts from our textbook to explain what the CEO might mean by “hustle and building relationships.”

Creative online activist strategies in Black Lives Matter and beyond

Black Lives Matter campaigns have deployed several strategies that were key to the EZLN campaign, as well as to other online activist movements. To make it easy to understand the strategies these movements deployed in common, I will list them and describe them in the next section.

Five strategies deployed by creative online activist movements:

- 1. Speed

- 2. Visuals

- 3. Performances

- 4. Inclusiveness

- 5. “Masked” leadership

1. Speed

Like the Zapatista online campaign, it was crucial in 2015 that Black Lives Matter protestors mobilize with speed. Responding fast to the actions of government or authorities allowed both movements to gather large publics when outrage over authorities’ decisions was high. In Black Lives Matter, an immediate response also sent the message that this public would not tolerate police violence any longer – effective immediately.

2. Visuals

In both the Zapatista and Black Lives Matter movements, campaign organizers gathered attention through effective use of visual content. Images of the masked Zapatista army are still widely circulated online. This article in WIRED Magazine explores the spreadable content of the Black Lives Matter movement, especially the visuals – photographs easily shared online that evoked the in-person experience of being black, in protest.

3. Performances

We must also remember the performances involved in each of these protests. The Zapatistas called a truce at a dramatic moment that would have cast the Mexican government as the villain if they continued to fight the small EZLN army. In Black Lives Matter, hashtags like #handsupdontshoot remind us that these protestors moved together in synced gestures that gave tremendous energy to their on-the-ground protests. Reenactment has also been an effective performance strategy, exemplified in protestors using the #icantbreathe hashtag to reenact the video of Eric Garner dying after police ignored his repeated pleas of “I can’t breathe.”

Online activism scholar Paulo Gerbaudo phrases it this way: Online media can be used for the “choreography of assembly” in organizing on-the-ground demonstrations. That is, online organizers can choreograph individual acts of cultural repetition (memes, discussed more in Chapter 7), such as clothing or gestures protestors can repeat to recognize and reinforce one another’s work. And they can organize the meeting places, escape routes, and conduct of massive groups of people. Gerbaudo notes that these actions can influence public consciousness most powerfully when they occur in a symbolic center – some meaningful public place that serves as a theatrical stage for activism to be seen and performed. A park at a city center, a football field, the Olympic medal ceremonies, a memorial statue: All of these have been symbolic centers for protest in the US and abroad.

4. Inclusiveness

Black Lives Matter’s strategy was also similar to the Zapatistas’ in the inclusiveness of the campaign. It was understood and stated by those in the movement that women must have equal access to the rights being fought for, and that in-family violence was part of what they were fighting. In Black Lives Matter, rights around gender and sexuality were always part of the discussion, as exemplified in this movement “herstory.”

Today’s social media-fueled movements tend to use rhetoric that acknowledges differences in power among the people they fight for or represent. This sets modern rights campaigns apart from some rights movements in the past. Both the Civil Rights and Black Panther movements focused on black men more than other citizens. The 20th-century women’s rights movements focused more on white women than any others. The 20th-century gay rights movement centralized the identities of white gay men. “Not your grandfather’s civil rights movement,” is one way Black Lives Matter has been described, reminding us that today’s movements broaden the focus from fathers and grandfathers to the rest of the family, the organization, and the community.

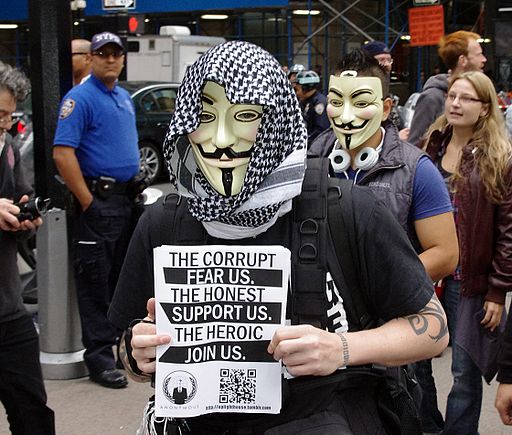

5. “Masked” organizers

In modern online activism, leaders wear masks – literally, and sometimes, figuratively. In the 20th-century, a much-remembered feature of social activism campaigns like the Civil Rights Movement was their visible leadership and culture of “heroes.” Dr. Martin Luther King is commonly remembered as the “father” of the Civil Rights Movement. Meanwhile, as this article by Jamil Cobb on Black Lives Matter reminds us, there were other strategies at work in the Civil Rights movement as well as leaders who shunned the spotlight, like Ella Baker of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Today, the branding has shifted, with many declaring today’s online activist movements “leaderless.”

The Zapatista spokesman Subcomandante Marcos was a bridge between these two styles of organization, the 20th-century heroic leader versus the 21st-century decentralized campaign. Marcos was the Zapatistas’ most visible “hero.” But he wore a mask, hid his true identity, and chose the false title of “Subcommander” (subordinate Commander) rather than “Commander.” A decade later, the “hacktivist” group Anonymous began organizing actions on 4chan in which the identities of the organizers and participants were not known; Anonymous made significant appearances during protests against the World Trade Organization. More recently, there have been figurative masks on many popular online movements including Occupy Wall Street, with all insisting there are no leaders. The strategy of “masked” organizers makes a movement difficult to defeat, while also resisting the persistent surveillance that is a function of the internet, and that can get activists jailed or killed.

Advancing and and complicating social activism through online engagement

There are many critiques of online activism as inferior to more traditional forms of activism. For example, techno-sociologist Zeynep Tufecki argues that by removing the hard work and shared risk of social organizing, social media technologies gather demonstrators too quickly for them to understand one another and think together. In another critique, scholar Evgeny Morozov uses the term “slacktivism” to characterize certain low-risk levels of “activism” such as signing online petitions, which offer participants the illusion they are contributing significantly, at zero risk to themselves. While these critiques may overlook the subtle shifts in the public consciousness that online chatter can effect, they have merit. As illustrated by the Zapatistas in Chiapas and Black Lives Matter in Missouri, online activism is at its most powerful when on-the-ground action provides roots to online campaigns.

However they are branded, successful online activism movements are never dependent only on leaders, and they are also never leaderless. Rather, modern activist movements in the US in particular are often ignited through interactions between key driving forces or personalities, and then mobilized networked groups of people who respond together. This idea, which author David Karpf has called an “organizational layer” of American political advocacy, may be the closest we can come to accurately describing the real effects of the internet on how we do activism.

Core Concepts and Questions

Core Concepts

creative online activism

activist movements that deploy creativity in using the affordances of the internet to promote activist agendas and avoid the pitfalls of oversimplification and appropriation

Zapatistas

an army of mostly poor, rural, indigenous people rose up against the Mexican government in 1994, and successfully used the early internet to reach out for witnesses and support

Janus Faced

a symbol, derived from ancient Roman mythology, of something that simultaneously works toward two opposing goals

information warfare

the strategic use of information and its anticipated effects on receivers to influence the power dynamics in a conflict

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

an agreement between the US, Mexico, and Canada in the early 1990s forging interdependence between their economies, including subsidies for corporations taking over Mexican land to grow cheap crops

Black Lives Matter

a sophisticated movement online and offline, fueled by outrage over injustices against black citizens by American institutions including law enforcement today

Five strategies deployed by creative online activist movements:

Speed, Visuals, Performances, Inclusiveness, Masked leadership

choreography of assembly

Paulo Gerbaudo’s term describing how successful online organizers preplan social activist movements that will ensue on the ground

symbolic center

Paulo Gerbaudo’s term for a meaningful public place that serves as a theatrical stage for activism to be seen and performed, such as park at a city center, a football field, the Olympic medal ceremonies, or a memorial statue

slacktivism

coined by Evgeny Morozov, this concept relates to critiques of online activism as inferior to more traditional forms of activism, with organizing online perceived as so fast, easy, and risk-free, it results in insufficient gains or change

organizational layer

political scientist David Karpf’s term for the networked groups of people responding together who he argues form the most important agents for change in American political advocacy today

Core Questions

Related Content

Consider it: A new era in online activism?

First, read the article “The Second Act of Social Media Activism” by Jane Hu, published in June 2020 in New Yorker Magazine.

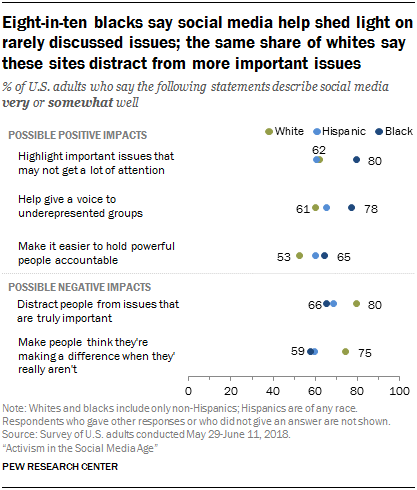

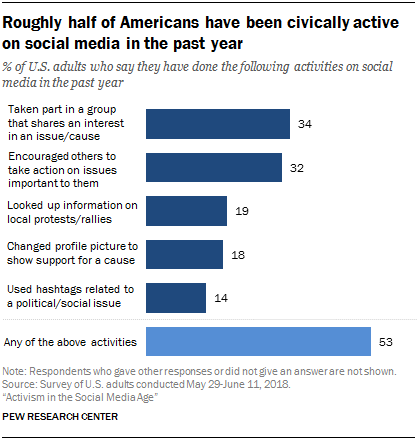

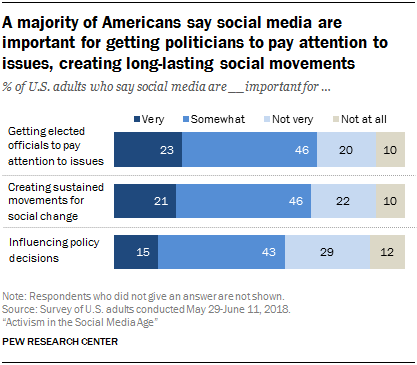

Also consider findings from the Pew Research Center’s 2018 study of American perceptions of the internet as a tool for social activism.

Techno-sociologis Zeynep Tufecki argued in 2015 that the tools to organize activist movements online may move too fast to build coalitions that “think together”. Whether that was true then, is it now? Support your answer, including what might you say to others in the Pew polls who think differently than you in order to explain your views.

Graphics by Pew Research Center.

Read it: Grassroots activists must consider the costs of digital campaigns (Delia Dumitrica, The Conversation)

Grassroots activists must consider the personal costs of digital campaigns

Mylynn Felt, Author provided

Delia Dumitrica, Erasmus University Rotterdam and Mylynn Felt, University of Calgary

Widespread use of social media has made it easier to mobilize collective action, yet citizen activists struggle to navigate these digital tools and increasingly report feeling burned out. Our research on grassroots digital activism in Canada has revealed some of the strategies organizers employ when dealing with the technological, interactional and personal barriers of digital activism.

People’s use of social media for activist purposes clashes with the commercial goals of these platforms. For example, as these platforms prioritize popular and recent content, activist messages have to be constantly updated and liked or shared in order to remain visible to wider audiences. This places the burden to adapt upon activists, who must make the best of these tools within the constraints set by the platforms’ algorithms.

Dilution or dissemination?

Social media can enhance activist communication at the cost of loss of control over the message. This matters in collective action, because a clearly communicated set of demands and complaints is essential to obtaining political recognition.

During the 2014 teachers’ strike in British Columbia, three parents came up with the idea of hosting playdates in front of the offices of members of the B.C. Legislative Assembly (MLAs). The parents wanted to pressure the provincial government to negotiate with teachers and end the strike. As they circulated the idea of #MLAPlaydates on social media, they reflected on the possibility of message dilution:

It’s not the traditional command and control. It’s like: here’s an idea, why don’t you play with it and see what you can do. You share, you pass on stuff.… So, it’s a different framework of activism.… It’s like beta testing, you don’t know where it’s going to fly.

Their solution was a form of “open-source activism,” which entailed monitoring social media to reinforce the message and prevent it from being co-opted, while inviting supporters to adapt and personalize this message.

Echo-chamber effect

Filter bubbles of like-minded people make it difficult for digital activists to get their messages outside of individual networks. Yet, some platforms are more public than others, using different algorithms to make content visible to their users.

Organizers of Alberta’s #SafeStampede wanted to call attention to the rape culture around the annual Calgary Stampede. They found that:

Facebook is far and away the best place to have actual discourse [around these issues], but again, you’re mostly talking to your own friends, so it does become a bit of a feedback loop.

To combat this barrier, organizers created public profiles on more open platforms like Twitter and Tumblr to breach the echo chamber effect.

Popularity contests

On social media, visibility is often enabled by the newness and reactions a message receives. Activists need to constantly monitor how algorithms push content to the top of other users’ newsfeed. This pressures them to think and act like digital marketers, strategizing their message production and circulation.

The digital activists in our research spoke to the necessity of adapting to platform-specific practices, as well as the learning curve of understanding these practices in the first place.

You have to be careful of the algorithms, so if you’re posting too much, you’re not going to get as wide of an audience.… With Instagram, if you posted three or four really good pictures with good descriptions and hashtags a week, you’re going to get more of a response than if you’re posting like, you know, five times a day every day. So, you want to be kind of conscientious in what you’re posting, and how often.

Allies and trolls

Alongside algorithms, interaction on social media brings along its own challenges to digital activism.

For the #SafeStampede organizers, social media platforms helped them find each other through their existing networks. Online connections grew into face-to-face meetings and relationships, facilitating critical backstage efforts to their public social media campaign:

I don’t think anything exclusively happens on social media anymore. There needs to be a point where things transcend social media and you end up having real conversations with people and you build relationships.

Social media also opened the campaign up for abuse and trolling. This was also the experience of another gender-related movement, the Women’s March in Alberta. The organizers described how people searching terms like “transgender” and “pussy hat” launched a gender-biased calculated attack a few days before the march. To deal with the backlash, the organizers resorted to a strategy of “block, delete, report, repeat,” pointing out that:

It had to be done, and we just tried really hard not to let all of our time and emotional energy get sucked up by that.

The camaraderie built online and offline helped mitigate the toll of these confrontations. Still, online attacks and trolling can easily deplete the already scarce resources that citizen activists have at their disposal.

Burning out and dropping out

While our participants minimized the personal and professional costs of their digital activism during our conversations, they also spoke of burnout making long-term involvement unsustainable.

The emotional cost of trolls, backlash and hyper-aggression on social media was difficult for organizers to escape as social media tied their public names to their activism:

You attract negative comments on you … attract people who feel they have the right to attack you … I try not to think about this too much, having too much information out there leaves me open to potential stalkers, or people who want to harm me or my child.

Distancing one’s self, either from the movement or from the potential risks of your activities, seems to be the only possible strategy for organizers in these situations.

Furthermore, because social media algorithms display the messenger alongside the message, organizers also expressed concern that their visible activism may create potential career risks.

Digital organizing strategies

The citizen activists interviewed in our research employed various strategies to navigate barriers to digital activism. Here are some of their lessons for other activists:

- Stay up-to-date with how algorithms are designed and updated for the platforms you are using.

- Use multiple platforms to reach different audiences and mitigate the effects of echo chambers.

- Allow some for some change in your message, but monitor the conversation in order to maintain its core.

- Connect with fellow organizers and supporters offline.

- Join a local, regional or national collective so you have fellow activists to lean on and pass the baton to when you need to step away.

- Anticipate the costs and risks of activism, and reflect on where you need to draw your own boundaries.

- Build flexibility and adaptation into your tactics of action.

While digital activism can be a crucial part of any successful campaign, activists needs to remain aware about the costs and limitations of social media.![]()

Delia Dumitrica, Associate professor, Department of Media and Communication, Erasmus University Rotterdam and Mylynn Felt, PhD Candidate, Communication, Media and Film, University of Calgary

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media Attributions

- Zapatistas © ilf_ is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Nafta is licensed under a Public Domain license

- 512px-Subcomandante_Marcos © tj scenes / cesar bojorquez (flickr) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- JN_image-5fcfe8ddd856f © Jessica Nickerson adapted by Emily Gammons is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 512px-Infobox_collage_for_MENA_protests © HonorTheKing is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- LW_image-5fcfd98a163ca © Lilly W adapted by Emily Gammons is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- SM_file-5fb37169714aa © Anonymous adapted by Emily Gammons is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1_Year_Commemoration_of_the_Murder_of_Michael_Brown,_the_Ferguson_Rebellion,_&_the_Black_Lives_Matter_uprising._(20426285322) © The All-Nite Images is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- BLM_28 © Fibonacci Blue is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- handsup © Debra Sweet is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 512px-Occupy_Wall_Street_Anonymous_2011_Shankbone © David Shankbone is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

activist movements that deploy creativity in using the affordances of the internet to promote activist agendas and avoid the pitfalls of oversimplification and appropriation.

an army of mostly poor, rural, indigenous people rose up against the Mexican government in 1994, and successfully used the early internet to reach out for witnesses and support.

An agreement between the US, Mexico, and Canada in the early 1990s forging interdependence between their economies, including subsidies for corporations taking over Mexican land to grow cheap crops.

a symbol, derived from ancient Roman mythology, of something that simultaneously works toward two opposing goals.

the strategic use of information and its anticipated effects on receivers to influence the power dynamics in a conflict

a sophisticated movement online and offline, fueled by outrage over injustices against black citizens by American institutions including law enforcement today

Paulo Gerbaudo's term describing how successful online organizers preplan social activist movements that will ensue on the ground.

Paulo Gerbaudo's term for a meaningful public place that serves as a theatrical stage for activism to be seen and performed, such as park at a city center, a football field, the Olympic medal ceremonies, or a memorial statue.

coined by Evgeny Morozov, this concept relates to critiques of online activism as inferior to more traditional forms of activism, with organizing online perceived as so fast, easy, and risk-free, it results in insufficient gains or change.

Political scientist David Karpf's term for the networked groups of people responding together who he argues form the most important agents for change in American political advocacy today.

Speed, Visuals, Performances, Inclusiveness, Masked leadership