Well-being (with Alexandria Fripp)

“The Internet can crack us open to seeing so many things that we would have never encountered otherwise. And that’s one of the most beautiful, miraculous things about it. But it can also divide our attention and make us feel fractured.”

Chris Stedman, author of IRL: Finding Realness, Meaning, and Belonging in our Digital Lives.

Is social media good for us? Is it bad for us? Can it be both? Research findings suggest many complex ways the use of social media platforms can impact our mental and physical health and well-being. In this chapter, we discuss a few relevant findings on social media—along with the voices of students who are consistently negotiating these issues in their lives.

“Teens blame Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression,” a slide from an internal Facebook presentation said. Among teens who reported suicidal thoughts, 13% of U.K. users and 6% of U.S. users traced those feelings to Instagram. https://t.co/xrdPBadIDp pic.twitter.com/omTI8I83DG

— The Wall Street Journal (@WSJ) September 14, 2021

Dimensions of Wellness and Well-being

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), wellness is defined as, “a dynamic state of physical, mental, and social well-being.” However, the term “wellness” has become so popular as a marketing buzzword that it has countless meanings to different publics. For clarity, in this chapter we have chosen to use the term well-being, defined by the APA as, “a state of happiness and contentment, with low levels of distress, overall good physical and mental health and outlook, or good quality of life.” In this section, we introduce the next part of the chapter as a dive into each of these three dimensions—with the understanding that these dimensions overlap and interact with one another regularly.

Physical health (and body image)

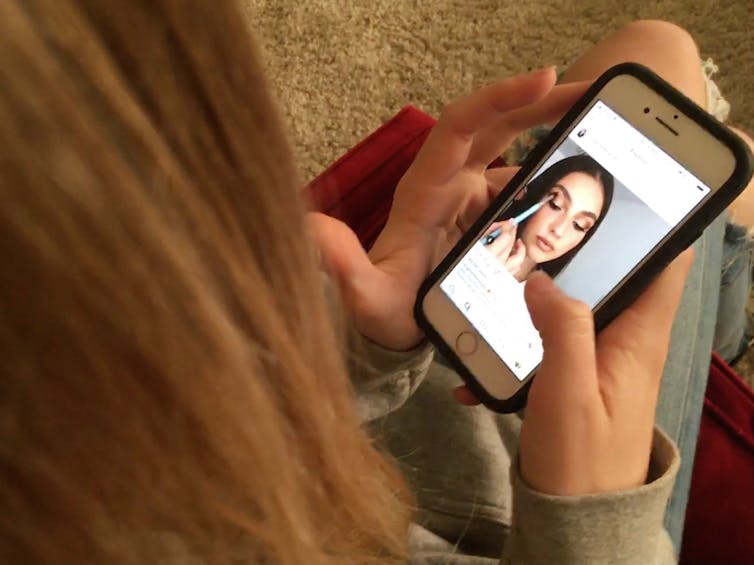

One wellness dimension is physical health. Social media may be associated with physically health improvements due to nutrition advice or “fitspiration”, and to problems with physical health caused by learning of unhealthy behaviors. One striking link between social media and mental health lies along the line of body image and satisfaction. For our social media aficionados, think about how many images of people we see each day. What do these folks look like? Do they have “Instagram Face”? Conventionally attractive? White? Thin? Able-bodied? Consider critically the seemingly perfect lives and bodies you see, comparing yourself to the images of these people, especially women, that may be surgically enhanced and/or heavily filtered.

Facebook, the parent company of Instagram, has conducted informal investigations of the app (Instagram) to see how it affected the relationship one has with their body. Approximately 32 percent of young women report feeling worse about their bodies after using Instagram. Moreover, the young women attribute Instagram for increases in the rate of anxiety and depression,” tying in the cyclical nature of depression and/or anxiety in relation to social media as shown by Hoge, Bickham, & Cantor (2017). Some of the adverse effects are thought to be Instagram specific such as social comparison, which is when people assess their own value in relation to the attractiveness, wealth and success of others.

The Facebook researchers state that social comparison is worse on Instagram than other platforms, asserting that TikTok is grounded in performance, Snapchat is “sheltered” by jokey filters that “keep the focus on the face.” Meanwhile, Instagram focuses heavily on the body and lifestyle. However, the research team concluded this in 2020. Their findings may not hold up to the current social media landscape, with the prevalence of Tik-Tok and the affordance of video filters to edit people’s bodies. For Instagram specifically, the researchers note that essential aspects of the platform such as norms around sharing only the best moments and the pressure to look perfect combined with an “addictive product” can send young folks “spiraling toward eating disorders, an unhealthy sense of their own bodies and depression.” The internal researchers further state that the Explore page, curated by an algorithm can show harmful content.

In “The Paradox of Tik Tok Anti-Pro-Anorexia Videos” by scholars Logrieco, Marchili, Roversi, and Villani (2021) , the shifting stances around anorexia depiction content on TikTok is paradoxically encouraging harmful behaviors. The, “What I Eat in a Day,” format is a common form of this. Moreover, the numerous “Glo-Up” challenges on the platform reinforce beauty standards (and generally come with weight-loss), while staying away from fostering unconditional self acceptance. Like Instagram, there are beautification filters which slim and anglify the appearance of the face. What messages could people, especially people who do not fit racist, thin, or ableist societal standards of beauty internalize?

Meanwhile, many youth consider TikTok a respite from more overtly image-conscious apps like Instagram. Although Tik-Tok was released in 2016, the height of its popularity came about in 2020. Thus research has yet to catch up to the trends we are seeing on this platform. However, that does not mean that we should not think critically about how this platform is used, what is happening on this app, and the media we consume from it, and all platforms we use, when considering their impacts on physical health.

Mental health

Another wellness dimension we are exploring related to social media is the second dimension, mental health, including anxiety and depression, as well as emotional regulation. In the digital age, social media can play a powerful role in our stress, happiness, and mental health. Social media has the capability of being a powerful tool in our wellness. For instance, many “mindfulness” podcasts have social media accounts where they share health experts’ tips on mindful living.) However, social media also has the potential to damage mental health and wellbeing as well—and as whistleblowers revealed in 2021, social media platforms may be aware of these impacts, yet do little to stop them.

Darkness that Stems from Light

Consider the mental health component of wellness. How does social media affect that in your life? In this previous story the author (Kyra) delves into literature about social media and mental health that describes social media reinforcing a cycle of emotional avoidance by providing a digital distraction from emerging anxiety or negative emotions. Kyra’s interpretation of this is that by escaping these feelings, we do not learn how to properly emotionally regulate- something that is core to our human experience of feeling and emoting. The article Kyra mentions delves even deeper.

The article Kyra refers to is authored by Hoge, Bickham, & Cantor (2017), in it the researchers explore the impact of digital technology on children’s well-being, specifically anxiety, depression, and emotional regulation. The authors found that individuals who overuse or are addicted to the internet use the internet to avoid negative affect such as anxiety and depression. (this brings into question, what is overuse? More casual relationships have not been studied at the time this article had been written). This problematic internet usage is associated with poor emotional regulation.

About the Audio Creator

Kyra Tidball is a Veterinary Science major at the University of Arizona. She loves coffee and reading a good book.

Kyra Tidball is a Veterinary Science major at the University of Arizona. She loves coffee and reading a good book.

Respond to this case study… This student compares social media to drugs and asserts that people are often unaware of what they are getting into when they download it. Imagine you have the opportunity to help decide if warnings should come with social media downloads. Write a paragraph either (1) explaining whether you would support such warnings appearing, how they would function, and what they would say; or (2) why there should not be warnings, based on evidence. Then, write another paragraph in which you imagine you were introducing someone you care about to social media use for the first time. What would you tell them is a healthy practice? Include the practice, and evidence of how you know it is healthy.

Emotional regulation is a vital part of mental health. Specifically, it is a skill developed in childhood and adolescence by experiencing strong emotions and developing internal regulatory processes. Having this skill is a tool. The lack of and problems with emotional regulation are associated with mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, conditions that individuals who “overuse” the internet report using the internet to avoid. Moreover, research has shown that depression symptoms predict internet usage to regulate mood. Thus our internet and social media use can be seen as a feedback loop, using the internet to avoid emotions, not emotionally regulating, experiencing emotional distress, then back to using the internet to avoid emotions once more.

Social media can be a mixed bag when it comes to our mental health and well-being. Hoge, Bickham, and Cantor (2017) state that , “although there is evidence that greater electronic media use is associated with depressive symptoms, there is also evidence that the social nature of digital communication may be harnessed in some situations to improve mood and to promote health-enhancing strategies.” They further state that much more research is needed to explore these possibilities. In what ways can social media help us connect with others and positively contribute to our mental well-being?

Social Health

Another important wellness dimension and another is social health. Access to technology was a lifeline for many at the start of the pandemic. We limited our in person social contact as many businesses, schools, restaurants, and workplaces shut down or reduced capacity for the initial quarantines. According to Pew Research Center (2021), the internet has been personally important to 90% of adults with 58% saying the internet has been essential. Since the beginning of the pandemic we have relied on the internet and digital world to connect with others, whether family, friend, or for school.

Pew Research Center (2021) reports that about 81% of Americans have utilized video calls since the onset of the pandemic, and many researchers have found sharp increases in social media use since the pandemic began. Social media have become vital connection points to work, school, and social networks—our connections to nearly all other people when in person contact was scarce. However, these findings are complicated by the digital divide, as affordability and connection issues are frequent barriers to internet access and thus to connection with other people.

Dr. Stephen Rains on Coping with Illness Digitally

In his book, Coping with Illness Digitally (2018), Communication researcher Stephen Rains outlines how the digital landscape connects folks to find community while living with illness. However, many of his findings can be generalized to how we connect and find community online generally in relation to our social health. The technologies we use to connect with each other in order to communicate can be referred to as communication technology. This includes our phones, messaging apps, blogs, and other platforms. The use of these according to Rains is motivated by a desire to overcome isolations, reach others similar to use, and strengthen existing relationships with friends and family. Communication technology is similarly used by a large number of American adults and settings like online communities, platforms, and blogs are resources for support that is associated with well being. Informational and emotional support are common types of support found in online communities.

Rains identified four affordances to creating social support, including control, anonymity, visibility, and availability.

- Control relates to the ability to manage aspects of human interaction, like editing a message before sending it. This is quite contrary to face to face interactions where one is unable to do that. This allows people to carefully curate messages.

- Anonymity is the concealing of one’s identity from others. This can be seen by the use of pseudonyms. Think back to the ASKfm days or how reddit is used to gather support. It allows folks to feel less nervous about asking questions online.

- Visibility is the affordance that involves the degree of observable behavior online. This allows folks to observe their digital landscape (ie: a viral twitter thread) or who gets to see a post. In the area of social support, seeing how others go about a situation or do something can be a valuable resource to us.

- Availability is the potential to connect with others when they are most needed (Rains, 2018).

Together, according to Rains, these affordances enable us to seek social support online to cultivate community, connect with friends and loved ones, and find support online.

Respond to this case Study: Think of a time when you have asked or you have seen other ask a question related to physical or mental health in a forum, on your story, or in any other online format. How did that go? What was that process like? Did people respond? If so, how did they respond?

We must also consider links between social media and social anxiety, or fear of embarrassment or humiliation, leading to the avoidance of social situations. The social media landscape is a wonderful way for us to connect to other human beings. On the other hand, it can lead to some distress as well. According to Hidge, Bickham, & Cantor (2017), the preference to communicate over text/IM/email over face to face increases the risk of social anxiety in folks that are more prone to develop it. Over time, choosing to substitute digital media for interpersonal communication to avoid feared situations (that can trigger anxiety) may become cyclically reinforced. Thus, this is yet another cycle. An individual prefers digital communication and displaces face-to face interactions, which may worsen the symptoms and severity of social anxiety, leading to the individual using the internet and social media again as an emotional outlet.

Social media has the potential to initiate and sustain relationships. Given the potential benefits of social media, perhaps we should consider how to navigate it intentionally to protect ourselves and well being. After all, these technologies will be with us for a while. It’s not going anywhere any time soon. Knowing that, how can we protect ourselves and our mental well-being? Technology and people can mutually shape each other (Ellison, Pyle, and Vitak, 2022), but in order to do so we have to rethink our relationship to social media and realize how our behaviours can actively and positively contribute to the virtual landscape.

Managing social media’s impacts on our wellness

NPR Lifekit episode of rethinking our relationship with social media

https://www.npr.org/player/embed/1016854764/1018979012

NPR’s Lifekit gives us some considerations to keep in mind when defining or rethinking our relationship to social media. Keep these in mind:

- Social media is designed to encourage repetitive behaviors and compulsions, but social media is not physically “addictive” in the same way as drugs and alcohol.

- features like pull to refresh, endless scroll, autoplay and the algorithms are intentional choices made to keep us on the apps by showing us more of what we might like

- Push notifications, (Made) For You Pages, Click to See Image are all tactics to capture our attention

- Remember: “Technology and people can mutually shape each other” (Ellison, Pyle, and Vitak, 2022). How might the above features keep us on platforms?

- think of your relationship with social media as a meaningful one with the capacity to show certain aspects about ourselves. Ask yourself:

- What does a healthy relationship look like to me?

- What needs am I trying to meet right now?

- Scan your body – how do you feel after an hour online?

- Be an active participant in your relationship – declutter and reorganize

- go through ‘following’ list on social media and clean it out – what is bringing joy and/or value into your life

- block, mute, and other functions let you restrict the kind of content you don’t want to see, which further fine tunes your algorithm to you.

Personal Conclusion

Is it possible to have a good relationship with social media? What steps can we take for positive impact?

Personally, I (Ally Fripp) can struggle with being bombarded by body types I feel are ideal that do not include mine. This weighs on me heavily some days, but I have to understand that these images are not always natural and real. Thus in order to give myself some tools combat this, I frequent a subreddit that spots body editing and am learning how to spot when other women use these filters and photoshop. Knowing that these folks don’t look the way they portray themselves on social media is comforting and fills the space in my mind for negative self comparisons.

Social media is here to stay for a while. And I actually do quite enjoy it. It can be a fun outlet. However, I can feel when it does take a toll on my mental health. Armed with the knowledge presented in this chapter, I take steps to protect myself. This includes taking breaks from social media, limiting my time on it, and being critical of the content that I consume. Our relationships with social media.

Related Content

The thousands of vulnerable people harmed by Facebook and Instagram are lost in Meta’s ‘average user’ data

By Joseph Bak-Coleman, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for an Informed Public, University of Washington

AP Photo/Eric Risberg

Joseph Bak-Coleman, University of Washington

Fall 2021 has been filled with a steady stream of media coverage arguing that Meta’s Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram social media platforms pose a threat to users’ mental health and well-being, radicalize, polarize users and spread misinformation.

Are these technologies – embraced by billions – killing people and eroding democracy? Or is this just another moral panic?

According to Meta’s PR team and a handful of contrarian academics and journalists, there is evidence that social media does not cause harm and the overall picture is unclear. They cite apparently conflicting studies, imperfect access to data and the difficulty of establishing causality to support this position.

Some of these researchers have surveyed social media users and found that social media use appears to have at most minor negative consequences on individuals. These results seem inconsistent with years of journalistic reporting, Meta’s leaked internal data, common sense intuition and people’s lived experience.

Teens struggle with self-esteem, and it doesn’t seem far-fetched to suggest that browsing Instagram could make that worse. Similarly, it’s hard to imagine so many people refusing to get vaccinated, becoming hyperpartisan or succumbing to conspiracy theories in the days before social media.

So who is right? As a researcher who studies collective behavior, I see no conflict between the research (methodological quibbles aside), leaks and people’s intuition. Social media can have catastrophic effects, even if the average user only experiences minimal consequences.

Averaging’s blind spot

To see how this works, consider a world in which Instagram has a rich-get-richer and poor-get-poorer effect on the well-being of users. A majority, those already doing well to begin with, find Instagram provides social affirmation and helps them stay connected to friends. A minority, those who are struggling with depression and loneliness, see these posts and wind up feeling worse.

If you average them together in a study, you might not see much of a change over time. This could explain why findings from surveys and panels are able to claim minimal impact on average. More generally, small groups in a larger sample have a hard time changing the average.

Yet if we zoom in on the most at-risk people, many of them may have moved from occasionally sad to mildly depressed or from mildly depressed to dangerously so. This is precisely what Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen reported in her congressional testimony: Instagram creates a downward spiraling feedback loop among the most vulnerable teens.

AP Photo/Haven Daley

The inability of this type of research to capture the smaller but still significant numbers of people at risk – the tail of the distribution – is made worse by the need to measure a range of human experiences in discrete increments. When people rate their well-being from a low point of one to a high point of five, “one” can mean anything from breaking up with a partner who they weren’t that into in the first place to urgently needing crisis intervention to stay alive. These nuances are buried in the context of population averages.

A history of averaging out harm

The tendency to ignore harm on the margins isn’t unique to mental health or even the consequences of social media. Allowing the bulk of experience to obscure the fate of smaller groups is a common mistake, and I’d argue that these are often the people society should be most concerned about.

It can also be a pernicious tactic. Tobacco companies and scientists alike once argued that premature death among some smokers was not a serious concern because most people who have smoked a cigarette do not die of lung cancer.

Pharmaceutical companies have defended their aggressive marketing tactics by claiming that the vast majority of people treated with opioids get relief from pain without dying of an overdose. In doing so, they’ve swapped the vulnerable for the average and steered the conversation toward benefits, often measured in a way that obscures the very real damage to a minority – but still substantial – group of people.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

The lack of harm to many is not inconsistent with severe harm caused to a few. With most of the world now using some form of social media, I believe it’s important to listen to the voices of concerned parents and struggling teenagers when they point to Instagram as a source of distress. Similarly, it’s important to acknowledge that the COVID-19 pandemic has been prolonged because misinformation on social media has made some people afraid to take a safe and effective vaccine. These lived experiences are important pieces of evidence about the harm caused by social media.

Does Meta have the answer?

Establishing causality from observational data is challenging, so challenging that progress on this front garnered the 2021 Nobel in economics. And social scientists are not well positioned to run randomized controlled trials to definitively establish causality, particularly for social media platform design choices such as altering how content is filtered and displayed.

But Meta is. The company has petabytes of data on human behavior, many social scientists on its payroll and the ability to run randomized control trials in parallel with millions of users. They run such experiments all the time to understand how best to capture users’ attention, down to every button’s color, shape and size.

Meta could come forward with irrefutable and transparent evidence that their products are harmless, even to the vulnerable, if it exists. Has the company chosen not to run such experiments or has it run them and decided not to share the results?

Either way, Meta’s decision to instead release and emphasize data about average effects is telling.![]()

Joseph Bak-Coleman, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center for an Informed Public, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media Attributions

- s21_099_p1gpp © Kyra Tidball is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

a state of well-being with dimensions including physical, mental, and social health

a state of happiness and contentment, with low levels of distress, overall good physical and mental health and outlook, or good quality of life.

a skill developed in childhood and adolescence by experiencing strong emotions and developing internal regulatory processes

fear of embarrassment or humiliation, leading to the avoidance of social situations