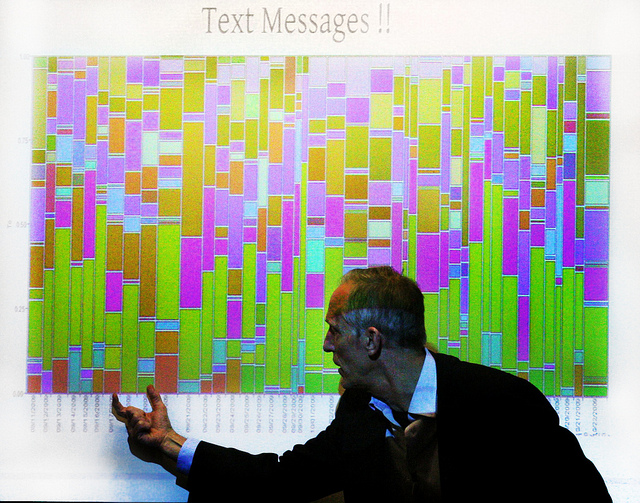

When you use social media, who are you communicating with? And who else is paying attention? This chapter is about producing, consuming, and controlling online content. It’s also about the data, cultural norms, and terms of service that you create, accept, and influence.

Section 1: Not “the public” – They’re publics, and they’re networked

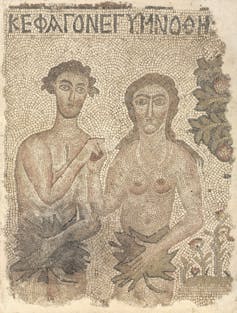

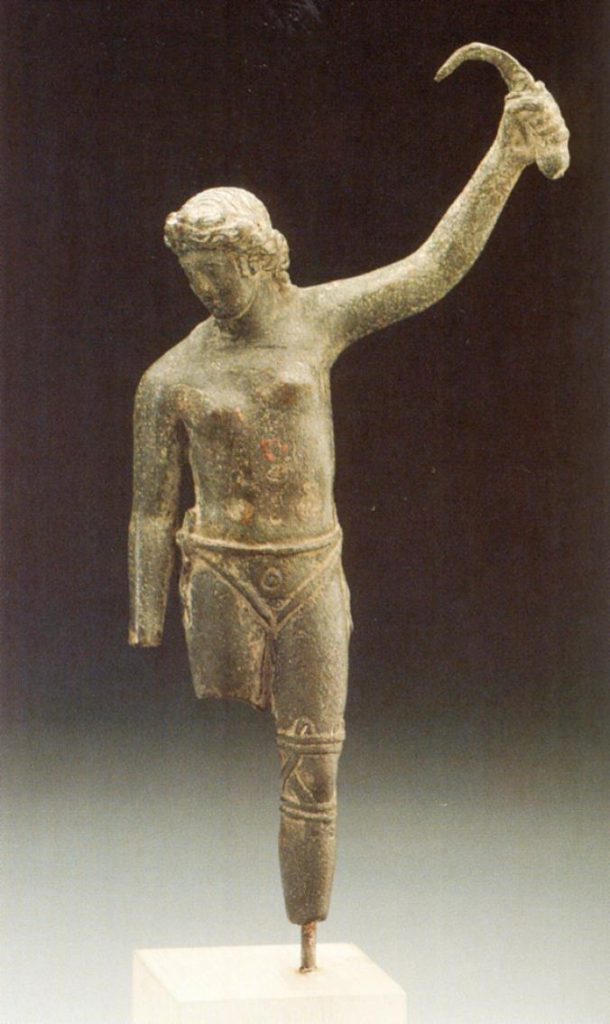

Let’s go back to that amphitheater in Chapter 2. We envisioned an athlete on the ground, spewing insults about her opponent. (Yes, there were women athletes and gladiators in Ancient Rome.) I imagine the athlete shouting, “I say before the public that my opponent has the stench of a lowlife latrine!” And we have a mass of spectators roaring in approval, disapproval, excitement, and laughter.

That mass of spectators is a public. The definition of a public is complicated (see danah boyd, It’s Complicated pp 8-9). But for simplicity’s sake, I define a public as “people paying sustained attention to the same thing at the same time.”

When the gladiator calls the mass of spectators “the public” it deepens the effect of her insult to suggest that “everyone in the world” is watching. Although it is imaginary, “the public” is a powerful idea or “construct” that people refer to when they want to add emphasis to the effects of one-to-many speech. But really, there is no “the public.” There is never a moment when everyone in the world is paying sustained attention to the same thing at the same time. There only are various publics, overlapping each other, with one person potentially sharing in or with many different publics.

If you use social media, you interact with many publics that are connected to one another through you and likely through many others. Publics that intersect and connect online are “networked publics” (pg. 8.) In the terminology of social network analysis, whenever an individual connects two networked publics (or any two entities, such as two other people), that connector is called a bridge. Think about the publics you form a bridge between. How are you uniquely placed to spread information across multiple publics by forming bridges between and among them?

Bridging information between publics can be exciting, and controversial. Networked publics really work each other up, forming opinions, practices, and norms together. And they occasionally get in fights in the stands, clubbing each other with ancient Roman hot dogs and Syrian tabouleh.

Student Insights: Navigating the ties and threats of networked publics (audio by Ibrahim Sadi, Fall 2020)

Section 2: Privacy Norms in Online Publics

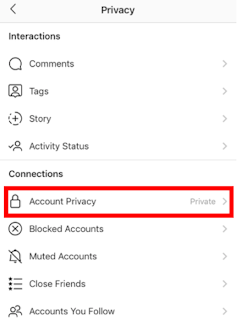

It is important to understand networked publics because they help us understand that the dichotomy of private vs public is an oversimplification of social relationships. When you post on social media, even if you post “publicly,” you probably envision certain people or publics as your audience.

Controlling the privacy of social media posts is much more complex than controlling the privacy of offline communication.

- On social media, as boyd notes, what you post is public by default, private by design (It’s Complicated, p. 61).

- Face-to-face, you can generally see who is paying attention and choose whether to speak to them, making your communications private by default, public by design. Note this is flipped from how it is on social media.

While popular media claim younger generations do not care about privacy, there is a great deal of evidence that youth care a lot about privacy and are developing norms to strategically protect it. Norms take time. There are norms that societies have developed over many centuries of face-to-face communication. These offline norms have long helped members of these societies get along with each other, and negotiate and protect their privacy. Let’s study one of these offline norms: civil inattention.