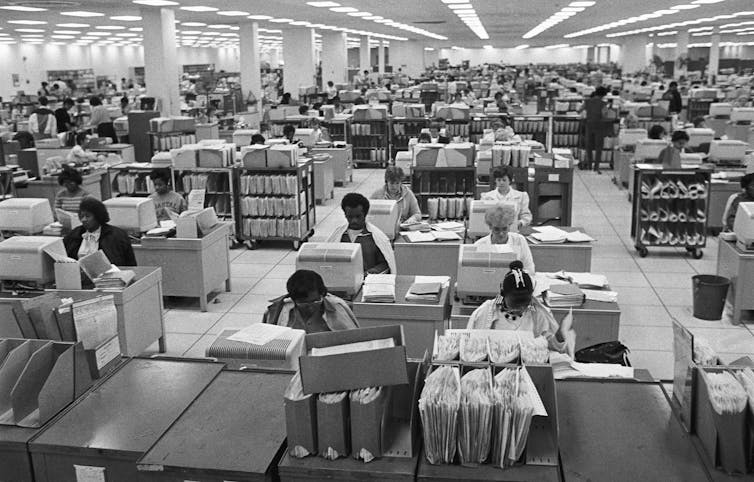

It is important to understand the relationships between older media and social media. By older media, I mean the industry-produced form of mass communication available in the US before digital social media became a thing, such as television, radio, newspapers, books, magazines, etc.

Older media can be referred to by other names, such as traditional media. And then there are subcategories of older media: broadcast media are one subcategory of older media, including television and radio, that communicates from one source to many viewers at once. Print media are a paper-based subcategory of older media such as newspapers, books, and magazines, that many users access.

Section 1: Media convergence

New digital media devices inherit many qualities and functions of older media and forms of communication.

Here’s an example: When your phone camera snaps a digital photo, it probably makes this sound or something like it. That sound is the sound of a shutter opening and closing. It is a sound that analog (non-digital) cameras have to make in order to function.

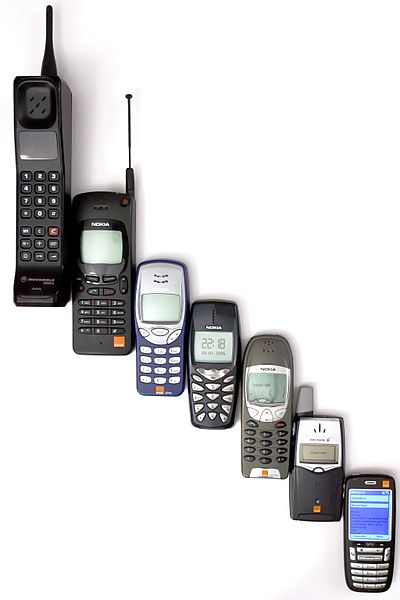

Digital cameras don’t have shutters; they function through chips that sense light coming into the lens. So why do so many digital cameras make that shutter sound? Because developers wanted your device to signal to you that the photo was taken, and that sound has become associated with picture taking in our society. Media scholar Henry Jenkins calls this type of blending of old and new media “technological convergence.” (Convergence just means coming together while moving through time.) Technological convergence is one of several types of media convergence that Jenkins writes are crucial to understanding our media world today.

Our technologies are full of convergences with older, traditional media helping us make sense of new media. Some signs of technological convergence go away over time as we become more comfortable with technologies. For example, mobile phones were once shaped more like analog phones, which helped people feel more comfortable calling and talking on them. However, as they gained more entertainment-related affordances, they began to appear more like remote control devices.

Student insights: My first encounter with technology (video by Anna, Spring 2021)

Section 3: A millennial shift: Web 2.0 as user contributions

It is with traditional media in mind that New York University Journalism professor Jay Rosen wrote The People Formerly Known as the Audience in 2006. He claimed that these people were taking over the media by using social media, and that his statement was their “collective manifesto.” He claimed the people were speaking out to resist “being at the receiving end of a media system that ran one way, in a broadcasting pattern, with high entry fees and a few firms competing to speak.”

Today’s media exist in a different era from the turn of the millennium. Rosen reminds us that broadcasters used to refer to viewers as “eyeballs.” Think about what that metaphor means. An eyeball has only two powers: To look, and to look away. There are plenty of media content creators who still only care about whether or not people are looking. But far more now allow users to “take part, debate, create, communicate, [and] share.” It increases their viewership, for one thing. And whereas the traditional media model involved advertising to the individual, the new model involves persuading the individual to advertise your product to their contacts.

The term Web 2.0 refers to sites that afford user contributions, such as likes and votes. O’Reilly Media coined the term Web 2.0 in 2004; you can read about that here. They were referring to social media sites popping up all over the web at that time. These new sites were different than the static sites of the 1990s and 2000s, the “Web 1.0” era. Web 1.0 sites would provide information or maybe some entertainment, but would not allow user contributions. You might say they were designed for eyeballs only – although creative users found ways to connect on Web 1.0, as we will learn when we learn about the Zapatistas in Chapter 5.

Web 2.0 sites that emerged in the early 2000s offered new capabilities, or affordances, to users. With Web 2.0 affordances, users can weigh in with likes and votes. They can comment or write their own posts. They can upload content, like images and videos. They can connect with others, and offer their own profiles and content to connect to.

Student insights: Simpler times (video by Luis A. Ruiz, Spring 2021)

Tools of change: Online cultures

The result of Web 2.0 is sites that are shaped by user cultures. Culture is a concept encompassing all the norms, values, and related behaviors that people who have interacted in a social group over time agree on and perpetuate. Think about the Web 2.0-enabled social media spaces you frequently visit. Perhaps when you spend time on Tumblr, you see that people talk about their emotions, and you talk about your own. Meanwhile, in League of Legends chat, you don’t talk about your emotions because you know you will get attacked if you do. On Facebook and LinkedIn, you might wear a high-buttoned shirt, as you have seen is the norm; but you might appear in a robe on Snapchat or a bikini on Instagram. Culture encompasses how users talk to each other, present themselves for one another, and take cues from and influence each other as they collectively decide what’s in and what’s out.

Software platform developers do influence culture in their user designs. For example, Facebook has its own shirt buttoned up rather high, with its plain white background and limitations on user customization of profiles. Online cultures do take some cues from developers, and users are restricted or guided by their affordances. But users have a lot of agency as they develop and share cultures within these sites.

Student Insights: Generations on Social Media (writing by Jaden Fernandez, Spring 2021)

Respond to this case study: How has your relationship with social media changed over time? Consider both how you have changed on a personal level and how the technology itself has evolved. Have you swapped platforms? Developed new habits? Found or left communities?

Section 4: Dominating today: The platform economy

…we are in the middle of a contest to define the contours of what we call the “platform society”: a global conglomerate of all kinds of platforms, which interdependencies are structured by a common set of mechanisms.”

– José Van Dijck and Thomas Poell, Social Media and the Transformation of Public Space. Social Media + Society, July-December 2015: 1.

Human-to-human connection is what social media is supposed to be about. This belief, this hope, was an impetus for this book when I began writing it in 2016. Historically, the human-to-human connection was also what the internet itself reached for, at least in the dreams of its creators. This Web 1.0 or the “read-only” web as it would later be called was quite limited in its reach compared to today. And yet…that potentially infinite web of networks was still a wonder, and a site of international connections and information wars (as you’ll see in Chapter 5 with the Zapatistas).

Then what happened? Well on the surface, the web simply became more social. By the early 2000s with Web 2.0 and the “read/write web,” great excitement and euphoria surrounded the participatory cultures that blossomed on Web 2.0 sites. The wonder of the web refracted across our lives, as we marveled at how easily we could connect with one another. This world of connections broadened our human imaginations and expectations in irreversible ways. And many were overjoyed when, by 2009, all this human connection grew teeth – which is to say viability in the form of real currency exchange – with the “sharing economy” that enabled regular folk to share services and goods with one another. Platforms that began as tiny businesses with few assets gained tremendous value as the places to go to socialize online, with family, customers, friends, and influencers. The more real or potential network connections we had who used a platform, the more certain we became that we had to use it too. In the platform economy, the more, the merrier. These network effects continue to drive audiences to platforms at dizzying rates, rapidly eclipsing product pipelines and business models that dominated in times past.

Behind the visible connections, all this sociality also marked the beginning of voracious – yet invisible – intermediaries. We were giddily giving up our data in exchange for the peer-to-peer exchange of services, a backroom exchange with implications few would recognize for nearly another decade.

And today? Welcome to the “platform society,” in which we are connected to one another, but only through platforms that derive immense power from and over our human connections.

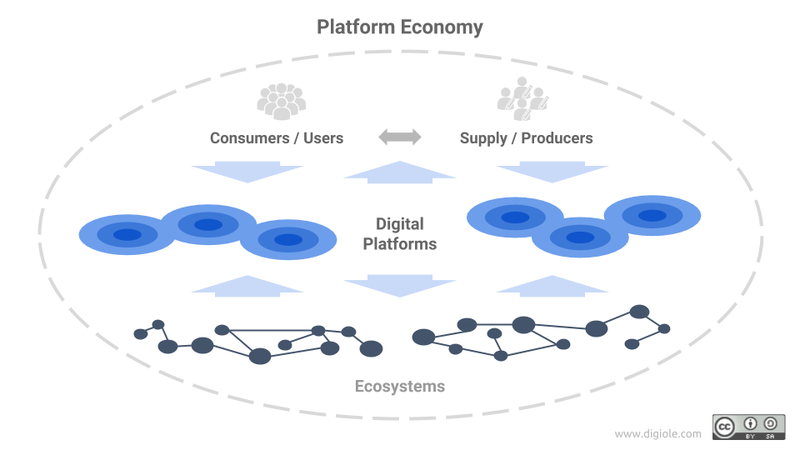

What are platforms?

I define a platform as follows:

Platform: An ecosystem that connects people and companies while retaining control over the terms of these connections and ownership of connection byproducts such as data.

Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon: These are the major platforms that José Van Dijck argues have defined how society and both public and private life function today. These platforms reach deeply into human lives worldwide, with their publicly understood purposes forming only a fraction of their activities and profits. And rippling from these big four platforms are smaller ones, which emulate their models in various ways. These platforms and their stakeholders transform not just what we buy and enjoy but what we need to live and thrive: how we educate, how we govern and are governed, and how we structure our societies.

The impact of globally operating platforms on local and state economies and cultures is immense, as they force all societal actors—including the mass media, civil society organizations, and state institutions—to reconsider and recalibrate their position in public space. (Van Dijk and Poell, 1.)

Platforms have a profound effect on how societal life is organized. Airbnb has changed not just the hospitality sector, but also neighborhood dynamics and social life. Uber has not only affected the taxi industry; it has affected the construction of roads and public transportation services. We do not yet vote through platforms, yet they have had irreversible effects on our elections. Today almost every sector of public life has become platformized: Higher Education. News and Journalism. Fitness and Health. Hospitality. Transportation. And in these platforms, transactions that are visible to consumers are undergirded by other transactions in which consumers become unwitting producers, their data a form of currency that subsidizes the transactions they chose to engage in in the first place.

Section 5: Future directions in the online world

With so much human activity and cultural expression enabled in Web 2.0, what is Web 3.0? Look this up on the web and you will find no shortage of responses. There is no consensus – no agreement among experts or among users. We don’t even know if we are already using Web 3.0, because it is hard to know where Web 2.0 ends.

Surely one valuable perspective on the present and the future of the internet would come from Tim Berners-Lee, who invented the World Wide Web (WWW) in 1989. (It was released to the public in the 1990s; read more of that history here.)

Today Tim Berners-Lee has a new mission – to make sure we really are connected by the internet. He describes what drove him to pursue this mission this way:

“Now people feel very disempowered, because the end result is that they’re telling their computer who their friends are, and who’s in the photographs, and planning things and designing things — and those plans and designs and friendships are sucked up and held by these social networks. And they’re not really social networks, they’re silos.”

The data you create as you move across online spaces is often controlled and owned by those spaces. Berners-Lee is now working to develop new methods of linking data across virtual space without relying upon governments, corporations, or the many others with an interest in controlling that data. You can read more about this new mission in this TechCrunch article.

“Right now we have the worst of both worlds, in which people not only cannot control their data, but also can’t really use it,” Berners-Lee said in the project’s announcement last year. “Our goal is to develop a web architecture that gives users ownership over their data.”

Student Insights: Old vs. New Media (audio & writing by Tyler Amberg, Fall 2021)

TASL: Music includes Melody 6 and Drums 3 from iVoices Innovation Pack by Gabe Stultz, iVoices Media Lab, CC-BY.

Respond to this case study: What affordances do you take for granted? How would your day-to-day life change if a technology you relied upon was no longer available? What might you substitute or repurpose to fill that need?