Section 1: A distorted mirror

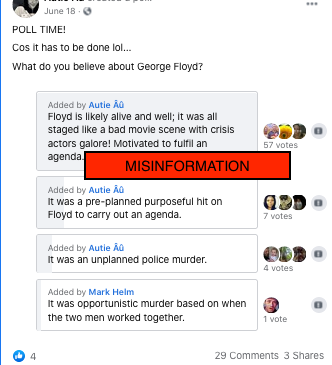

It’s June 2020. The streets host surging protests against systematic racism in the US, and polls show a majority of Americans in favor of the Black Lives Matter movement at the protests’ foundation. However, social media metrics show at least seven of the ten top trending posts on major social media platforms including Facebook and Twitter are highly critical of Black Lives Matter.

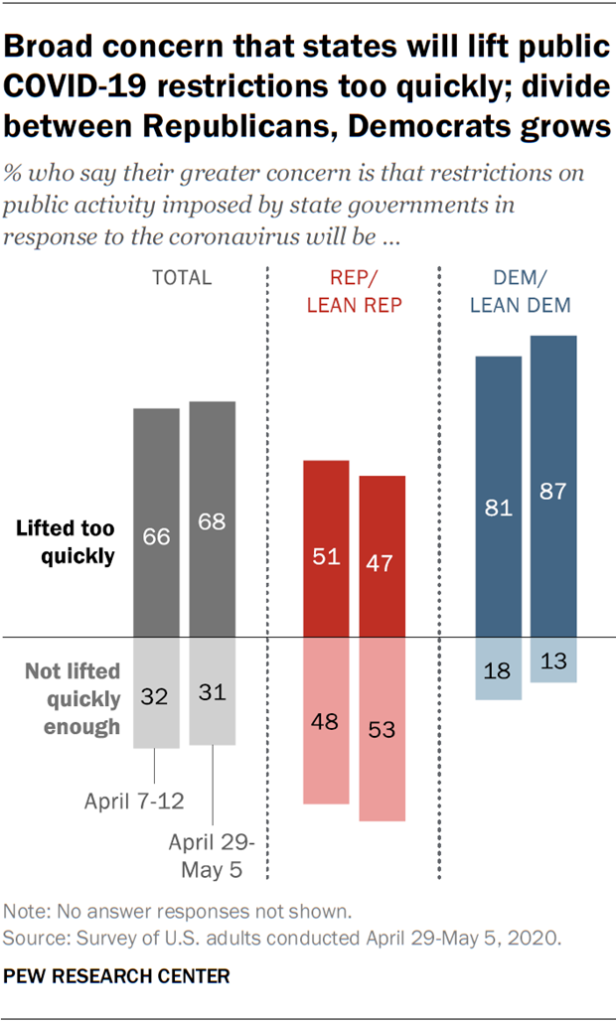

The mismatch seems unusual, except we don’t need to look far back to see other serious misrepresentations of the social world on social networking platforms. Another example began in May 2020. Polls showed a majority of Americans trusting medical experts on coronavirus, agreeing with coronavirus-related restrictions, and in fear of going to work with the virus still spreading. Nonetheless, posts about government overreach and misinformation skeptical of the coronavirus threat were top trends on social media platforms including Twitter, Facebook, and even TikTok. Drummed up and networked through connecting with these posts, in the midst of lockdown people staged “Reopen protests” that are widely covered by the media (including this author).

These mismatches signal important and often forgotten factors that distort social media’s image of public life in America. Social media are not simply mirrors of society. Social media platforms, content, and algorithms influence societies, and societies influence them, in continuous cooperation and struggle.

Social media metrics and feeds today offer limitless data and indications of what society is expressing today, but the science on new media shows this data is systematically skewed. They may show us only what we want to see, over-represent the ideas of entities who pay more or game the system, under-represent social groundswells developing offline, and leave some people or ideas out altogether. While they may reflect some of what people are talking about, social media insights can be more like funhouse mirrors than clear reflections.

While social media buzz does not simply mirror society, insights found on social media are not fully disconnected from real social life either. Understanding the nature and design behind the trends and even individual posts across social networking sites (SNS’s) can have great value in understanding networked communication, including the impacts of social networking on social life, and human social influences on SNS’s. One goal of this book is to guide the reader and participant through these complex layers of understanding.

Student Insights: Finding your voice in a connected democracy (writing by Trinity Norris, Fall 2020)

Section 2: A relationship of mutual influence

How are we influenced by social media? How is social media influenced by us? And why have this book title represent humans as social media? The swirl of life immersed in social media begins and ends with ourselves as active human players in it. We produce social media content, we consume it, and we create and influence social media algorithms. Human practices and tendencies feed the systems that produce feeds for us in turn. In the end, our own careful human interpretation of these feeds will produce knowledge about the mutual influence humans and social media have on one another. The explosion of social networking and Web 2.0 sites since the early 2000’s gives us an opportunity to examine how we do everything—relationships, work, social life, politics, government, and even life itself—through social media. This can tempt us to the overwhelming conclusion that the study of social media means the study of everything, everywhere. Luckily, we can always return to the basics, beginning with what social media are by definition.

What is / are social media, really? Consider the terminology. The term media is the plural form of medium, which is anything through which impressions or force are transmitted to affect things on the other side. Social describes the kind of media we are talking about because they relate to people interacting. The term social media usually refers to digital technologies that help people interact. So it’s technically correct to write “Social media are [awesome, stupid, elemental, detrimental, whatever].” But it’s also ok if you write “Social media is [changing the world, turning my friends into zombies, etc]” because the singular form is in common usage. I will use the term “social media” as both plural and singular in this book.

This is the thing about social media: it is grounded in how people talk and behave, not in rules set by any authorities. Almost any standards at work in social media can be changed by users if enough of us start pushing against those standards. We create social media. Tech developers respond to us as they create software apps, also known as software platforms. Then we tweak their apps, using them in ways that developers never planned because these unforeseen uses fit our lifestyles. Or we choose other apps that fit us better. And then those developers respond to us again.

And yes, social media does influence us too. But it can be surprising how much of what we do online was in practice in our society before social media became “a thing,” and how societal and cultural phenomena independent of technologies weave their ways into our online behaviors. Unpacking these influences requires explorations of history and theories in communication, sociology, anthropology, economics, and political science.

Section 3: Is this digital? Is this even new?

Human behavior today can appear utterly transformed by digital technologies. When we look more closely, there are many moments today that echo behaviors of the past before digital technology played a key role. And there are many societal changes that have a variety of causes, some playing much larger roles than technology. Still, people love to claim that technology has transformed society, perhaps because they benefit from the claim, or because it makes changing the world look easy with the proper tools. It isn’t.

The impacts of social media in our world are complicated. Misunderstandings around these technological platforms and practices in our world are common outcomes of flawed thinking or fallacies about this new force in our lives. In this section, we will break down some of these fallacies behind simplistic and exaggerated claims about social media in our world.

Utopian and dystopian thinking are among the most fallacies in thinking around social media. We are all familiar with utopian visions of social media – as though entering the golden gates of social media means leaving behind all the troubled communication practices that came before. A utopia is an idealized or perfect imaginary view of society. The utopian view sometimes imagines social media as a miracle disconnected from all prior human communication; other times, social media represents a more evolved social media world, where we have moved beyond all bias. The media theorist Clay Shirky conjures utopias as he describes social media’s effects on how we organize, as though they might connect everyone in the world. He is a great speaker; when I listen to him I feel comforted by the humming machines watching over us, extending our powers with God-like equanimity.

Click here for a captioned version of this video.

Conversely, it is also common to find social media use viewed as the downfall of society – a dystopia, or imagined society where everything is terrible. The increasing reliance of our society on social media for everyday communications looks nightmarish to some. Teens never look up from their phones. Computers make life-or-death decisions or at least remove humans from making them. Our brains are rewiring to cut out human emotions like compassion as we become robotically trained to pursue likes and connect with people we never see. Such dystopian thinking can make people jump to conclusions and even deploy data and scientific research as hasty “proof” of their extreme conclusions, leading to moral panics or fears spread among many people about a threat to society at large.

Technological determinism is among the broadest fallacies around social media use. Technological determinism is the belief that technologies are fully responsible for grand shifts in our world, instead of acknowledging the more complicated interplay of forces behind the phenomenon in question. While social media technologies have enormous effects on our lives, human cultural and societal factors are usually also at play. The following are two claims about social media that exemplify technological determinism and explanation of their more complicated realities.

Claim: Twitter “made” the Arab Spring.

A good example of hype around social media is in popular misunderstandings about the Arab Spring, an explosion of protests against governments in the Middle East in 2011. Contrary to many claims in the media, Twitter was not responsible for the Arab Spring. Twitter was an important tool there, but relationships sustained in face-to-face interaction, and old-fashioned protest in public spaces like Tahrir Square, were the foundations of the Arab Spring, as researcher Paulo Gerbaudo found and presented in his 2012 book Tweets and the Streets. Zeynep Tufecki’s research in the Middle East and in activist movements with online components has also found that while speed and ease were benefits of organizing movements online, toppling regimes as protestors in the Arab Spring accomplished required substantial offline interaction including countless cups of tea. Video footage from the Egyptian protests in media including the song lyrics and music video #Jan2 reveal intensely organized physical encounters.

Claim: Youth are addicted to social media, and this is a new phenomenon

Today’s North American teenagers choose to spend much more of their time with friends online, according to Pew Research Center, while past generations socialized more in person. However, there are many factors responsible for this other than today’s ubiquity of digital technologies. One factor is that youth are not allowed to be out as much as they once were. Today’s youth deal with parents who hover more closely and give them less freedom in public spaces than their parents were given themselves, and curfews and other restrictions remind teens that they are unwelcome in public spaces. For her 2014 book It’s Complicated, danah boyd conducted qualitative research, including interviews with teens and observations of their homes and neighborhoods. In her research, she found that teens were using social media to cope with physical restrictions on their mobility, pursuing social relationships online from their homes. Yet despite the lack of evidence around addiction, social media is associated with health concerns for all users and especially youth, due to content that exists only and the dynamics of its circulation and our communications. As U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy advised in 2023, “We don’t have enough evidence to say it’s safe, and in fact, there is growing evidence that social media use is associated with harm to young people’s mental health.”