4 G – H

g

The general factor found in cognitive tests reflected in the positive correlation among many diverse measures.

Gene

A gene is generally thought of as a sequence of DNA (found on a chromosome) that codes for a specific physical structure as well as (relevant to school psychologists) behavioral traits or characteristics.

General outcome measure (see curriculum based assessment)

Genetic similarity (among relatives)

Researchers, especially those concerned with environmental and genetic influences on behavior, often use the degree of shared familial genes as part of their research. Because it is now known that many psychological characteristics are heritable, it is sometimes also helpful for school psychologists to reference information about shared genes. The table below summarizes the degree of genetic similarity among relatives.

- Identical twins = 100%

- Father or mother = 50%

- Brother or sister = 50%

- Grandfather or grandmother = 25%

- Uncle or aunt = 25%

- First cousin 12.5%

Geodon® (see anti-psychotic medications)

Gordon Diagnostic System (see continuous performance tests)

Good Behavior Game (see group contingency interventions)

Grapheme

A grapheme is the smallest element of print (e.g., a letter).

Graphomotor

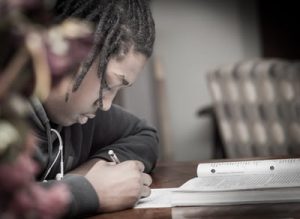

Concerns the ability to write, such as by use of a pencil or pen. The multiple components necessary for effective graphomotor execution have been identified by Berninger and Richards (2002).

- successful planning of finger movements

- executing finger movements with precise timing

- timing and coordinating of planning, executing, and learning (retaining over time) of movements

- actual motor control

- selecting the proper motor response

- final successful execution

Photo by Wadi Lissa, courtesy of Unsplash

As might be expected, graphomotor problems are common among students with written expression disabilities. Research by Virginia Berninger and her colleagues at the University of Washington suggests that graphomotor problems constrain successful writing beyond the simple initial stages of first learning to write (including composition by older students; Berninger, 2009). Consequently, this is an important area that should not be overlooked by school psychologists.

Group contingencies

This behavioral technique is defined as methods for dispensing reinforcement either dependent on the behavior of a group, rather than an individual, or receipt of reinforcement as an undifferentiated group rather than a single individual.

There are various options. For example, an entire class might receive a reinforcement (e.g., extra free time) contingent on the actions of just one of its student members (or a small group of students). As an alternative, an entire class (i.e., all class members) might need to achieve some level of behavioral success so that the entire class (i.e., all class members) become eligible to receive a reinforcement (e.g., extra class time). The former variation can be described as a “dependent group contingency,” whereas the latter can be described as an “interdependent group contingency.”

Variations in group contingencies notwithstanding, they appear to work. A meta-analysis (Maggin, Pustejovsky, & Johnson, 2017) of group contingency studies dating over four decades shows consistent effects, although most of the student behaviors targeted concerned either academic engagement or disruptive behavior. Additionally, most of the supporting evidence comes from general education students who are enrolled in late elementary school to late middle school. Even so, group contingency procedures seem to be one tool for school psychologists to consider when their consultation activities involve entire classrooms of students needing improved work habits and diminished disruptive behavior. Some examples of group contingency interventions are: Good Behavior Game (e.g., see Mitchell, Tingstrom, Dufrene, Ford & Sterling, 2014), Mystery Motivator (e.g., see Kowalewicz & Coffee, 2015), and Behavior Bingo (e.g., see Collins, Hawkins, Flowers, Kalra, Richard & Haas, 2018).

Haldol® (see anti-psychotic medications)

Head Start

Head Start is a federally funded program for preschool children and their families. Launched in the 1960s, Head Start was designed to help break a cycle of recurring poverty extending across generations. It envisioned a comprehensive set of services related to child development able to help communities meet the needs of disadvantaged preschool children. At present, Head Start serves more than one million children and their families each year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Currently, Early Head Start programs target pregnant women, infants, and toddlers, whereas Head Start picks up children once they reach three years of age. Most remain through age 4 years. Services address three things:

- Early learning

- Health

- Family well being

Details about Head Start are available at the following Department of Health and Human Services link: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohs/about/head-start

A program locator is also available at this link: https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/center-locator.

Hearing loss in children

School-age children may experience a hearing loss that mimics other classroom problems. In addition, younger children, such as those with documented special needs, may have hearing loss as part of their complex presentation. Consequently, all children undergoing psychoeducational evaluations should have completed a hearing screening. Those failing a screening should undergo an evaluation by an audiologist to address the nature and extent of any hearing loss. Several procedures are available. These include:

- Pure tone audiometry (simple test requiring youngsters to respond to various frequencies and intensities of sound)

- Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) or Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (BAER; an EEG-related technique that does not require active or voluntary responding by youngsters)

- Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE; a technique in which sounds are generated directly into the ear to allow detection of returning sound and permit inferences about hearing without a requirement for active or voluntary responding)

- Behavioral Audiometry Evaluation (changes in children’s behavior when various sounds, at various frequencies, are introduced)

More detailed information is available from the CDC link: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/screening.html.

The following link from NASP may be of assistance:https://www.nasponline.org/research-and-policy/policy-priorities/position-statements/serving-deaf-and-hard-of-hearing-students-and-their-families-implications-for-education-and-service-delivery.

Hemophilia

Hemophilia is a blood disorder characterized by lack of clotting factor and a risk of bleeding (e.g., from an open wound or within joints following a trauma). It is caused by an anomaly on the X chromosome, which means that females with this anomaly are carriers whereas males with it express the symptoms and signs of hemophilia. Hemophilia is important for school psychologists to appreciate because of the social and physical consequences associated with potential bleeding and because the condition appears to be a risk factor for ADHD and, potentially, school learning problems (Spencer, Wodrich, Schultz, Wagner, & Recht, 2009; Wodrich, Recht, Gradowski & Wagner, 2003).

The following links from the National Institutes of Health may be helpful: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/hemophilia/.

Additional information is available from the National Hemophilia Foundation: www.hemophilia.org/

Herpes simplex (see TORCH)

Heterogeneous (heterogeneity)

This refers to things that are mixed or diverse in type. Heterogeneity turns out to be an important concept because many conditions documented by school psychologists suggest a degree of homogeneity that may not exist. This is exemplified by the label specific learning disability (SLD). There is little homogenous about those students with SLD. SLD comprises students with diverse academic skill deficits (e.g., some in literacy, some in math), underlying problems (e.g., some in language, some in memory) and with divergent severity levels. Without appreciation of the heterogeneity associated with SLD, planning an effective program or anticipating future needs is constrained, a fact sometimes overlooked. Parallel considerations sometimes exist regarding clinical, not just administrative, labels. For example, students with autism (ASD) or ADHD are far from homogeneous.

HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)

A crucial federal law because it specifies how health service providers must protect the records and privacy of their patients. In general, schools are judged to be sites where HIPAA provisions do not apply. If health information is collected at school, it is typically considered to be for educational reasons. Instead, FERPA rules often apply.

The following link from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides details relevant to school-based practice: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/513/does-hipaa-apply-to-an-elementary-school/index.html

Homeopathic treatment (of ADHD)

This concerns ADHD treatment resting on a non-traditional theory of medicine and health care. It is important for school psychologists because homeopathic practitioners may suggest children consume dilute amounts of substances to improve their learning or behavioral condition, such as ADHD. In general, like most “complementary” ADHD treatments involving dietary changes or use of supplements, those aligned with homeopathy are not currently advocated by the National Institutes of Health.

For information about ADHD treatment, including some non-traditional options, see the following National Institutes of Health link: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/adhd/ataglance.

For additional information see the following link from the American Academy of Pediatrics: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/adhd/Pages/Homeopathic-Treatment.aspx

Huntington’s disease

An autosomal dominant disorder. An affected parent confers a 50% chance for the disease to each of his/her offspring. Although Huntington’s disease typically expresses its symptoms in adulthood, in some cases the symptoms appear during the school years. These consist of distortions in motor execution (chorea) and associated cognitive changes. The condition is also important to recognize because of its social consequences. Its midlife appearance means that special family stresses may confront some students. For example, students with a family history (e.g., a grandparent with Huntington’s disease) often live with parents who must either be tested for the condition themselves or wait to see if symptoms appear.

Additional information is available from the National Institutes of Health: www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease-Information-Page.

Huntington’s Disease Society of America also provides information: http://hdsa.org/

Hyperbilirubinemia (see neonatal jaundice)

Hyperlexia

Concerns abnormally advanced reading skills, typically consisting of particularly strong oral reading coupled with limited reading comprehension. Hyperlexia is sometimes seen as a savant-like capability among children with autism.