1 A – B

ABAB (see reversal ABAB design)

ABC (in applied behavior analysis)

Refers to “antecedents,” “behavior” and “consequences.” These three aspects are often used to conceptualize the cause of students’ behavior and to devise informed behavior intervention plans (also see behavior intervention plan).

Abilify® (see anti-psychotic medication)

Absence seizures

These were historically referred to as “petit mal seizures,” a term that school psychologists will sometimes still hear. The seizures consist of short lapses of consciousness, often characterized by a blank stare. Familiar and dramatic seizure signs (e.g., jerking, falling, loss of consciousness) are absent as are post-seizure drowsiness or confusion. When present in children, absence seizures can occur many times per day. They may be mistaken for ADHD. (also see epilepsy.)

Accommodation(s)

Typically concerns adjustments to instruction for students with Section 504 designations (also see Section 504 definition).

Adaptive behavior

Concerns mastery of self-care, communication, socialization, and functional skills needed to succeed in one’s daily environment. In school psychology practice, problems of adaptive behavior are typically screened for with subtests included in parent-completed rating scales (e.g., Behavior Assessment System for Children-Third Edition; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015) or assessed in-depth by lengthier and more detailed measures (e.g., Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-Third Edition; Sparrow, Cicchetti & Saulnier, 2016) that require interview of a child’s parent or caregiver. Limitations in adaptive behavior are one criterion for a diagnosis of intellectual disability (also see intellectual disability).

Adderall® (see stimulants and other ADHD medications)

ADHD medications (see stimulants and other ADHD medications)

Advance organizer

A teaching strategy to help students learn by offering them higher-level cues or “hooks.” The originator of the advanced organizer notion, educational and cognitive psychologist David Ausubel (2000), advocated an organized curriculum rather than less-structured discovery methods of learning. The logic is that advanced organizers aid students by having them link what is to be learned to what they already know. The effect is to make learning less rote and more meaningful and to facilitate learning and retention. Subsumed under the advanced organizer concept are diverse techniques exemplified by concept mapping and coaching students to pre-read (skim) before they read for meaning and retention. In other words, what is to be learned is organized in advance of learning itself. Research continues to demonstrate enhanced learning when instructional techniques tie pre-existing knowledge together with new information (e.g., Koscianski, Ribeiro, & Silva, 2012, in high school physics). This concept is important for school psychologists who sometimes recommend these strategies. Similarly, school psychologists might hear teachers discuss their use.

The following link from the State University of New York provides details:

http://people.sunyit.edu/~lepres/thesis/principles/19_pdfsam_POD.pdf

Affect and mood

Often assessed as part of a mental status exam, these two dimensions are easily confused. Mood refers to a state that is (generally) stable and internal in that it is known to the individual (Serby, 2003). Affect, in contrast, is external (thus observable) and subject to momentary changes. Thus, a teen might be described as having hypomanic mood with labile affect. School psychologists may encounter references to affect and mood in extra-school psychiatric reports. Some school psychologists may also describe a student’s affect and/or mood when they conduct a clinical interview. The table below indicates some commonly used terms as well as the meanings of those that may not be self-evident.

| Mood | Affect | ||

| Commonly-used descriptor | Everyday meaning | Commonly-used descriptor | Everyday meaning |

| “manic” | extremely elevated | “blunted” | extremely restricted |

| “hypomanic” | elevated | “constricted” | restricted |

| “euthymic” | normal range | “flat” | reduced |

| “dysthymic” | mildly sad | “inappropriate” | not fitting context |

| “depressed” | markedly sad | “normal” | unremarkable |

| “anxious” | anxious | “full range of” | varying across normal range |

| “irritable” | irritable | “lack of” | absence of |

| “incongruent” | inconsistent with one’s mood | ||

| “labile” | rapidly and unpredictably changing | ||

Affective disorder(s)

A general term denoting a mood disorder of some type. The conditions that might be included under this broad and imprecise label include persistent depressive disorder, major depression, bipolar disorder, and seasonal affective disorder. See DSM-5 (e.g., pages 123-188) for details on various affective disorders.

Agoraphobia

Literally fear of public or open places. In psychology, agoraphobia concerns avoidance of diverse settings outside the home, typically because a panic attack is anticipated or feared in these settings. For school psychologists, school avoidance coupled with anxiety/fear may suggest a problem akin to agoraphobia. Also see DSM-5, page 217.

Alopecia

Loss, or severe thinning, of hair on the scalp. This phenomenon may arise from chemotherapy, in which case the entire scalp is typically involved, or from selective hair pulling (trichotillomania), in which case bald patches often appear. Alopecia is important for school psychologists because of the obvious social stigma it engenders. If the cause of alopecia is trichotillomania, then school psychologists may help direct the family toward treatment or themselves initiate a behavioral program. Also see entry for trichotillomania.

Alphabetic principle

An early developmental accomplishment related to oral reading signaled by students’ realization that printed letters stand for sounds, which in turn can be grouped to form words. There appear to be large variations when children master this principle. For example, those residing in homes with few books or parents who seldom read may arrive at kindergarten with no sense of the alphabetic principle. In contrast, those coming from homes many books and parents who routinely read may enjoy solid mastery of the principles even prior to teachers starting formal reading instruction.

See the following link from the University of Oregon: http://reading.uoregon.edu/big_ideas/au/au_what.php#what

American Board of Professional Psychology (ABPP)

A credentialing agency concerning 15 areas of psychology practice, ranging from “behavioral and cognitive psychology” to “school psychology.” A credential is issued based on a review of professional preparation, work samples and oral examination. Practicing school psychologists holding this credential often add “ABPP” to their degree when they sign documents. This credential is restricted to psychologists licensed for independent practice in their respective state, effectively confining the credential to doctoral level psychologists.

The following link concerns ABPP generally, with information regarding school psychologists found at the same site: https://abpp.org

American Psychological Association (APA)

A large organization concerned with psychology broadly, including both its scientific and practice aspects. Consequently, APA encompasses a membership as diverse as university professors, practitioners in industry, as well as those in clinical and applied settings, such as schools. APA comprises 56 divisions, of which Division 16 is dedicated to school psychology. In general, membership in APA is restricted to doctoral level psychologists. Not surprisingly, APA accredits training programs for doctoral level psychologists. These include programs in school psychology. It also publishes its own code of ethics. Further, Division 16 publishes a newsletter, The School Psychologist, and a scholarly journal, School Psychology.

Some important APA links follow:

- Home page: http://www.apa.org/

- Division 16: http://www.apa.org/about/division/div16.aspx

- Ethical Principles and Code of Conduct of Psychologists: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

- Student Affiliates in School Psychology: http://apadivision16.org/sasp/

Anafranil® (see anti-depressant medications)

Angelman syndrome

Caused by a microdeletion in chromosome #15 in a mother’s egg. Strangely, this same microdeletion causes another syndrome, Prader-Willi, when it arises in father’s sperm. There is typically no family history; the syndrome is caused by random events. It is relevant to school psychologists because boys and girls with Angelman syndrome routinely express profound developmental disability, seizures, poor muscle tone, small head size, and unusual looking facial characteristics. They are typified by a happy disposition and floppy muscle tone, which led their condition to be described earlier as the “happy puppet” syndrome.

Additional information is available from the following NIH links: www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Angelman-Syndrome-Information-Page as well as from the Angelman Syndrome Foundation: www.angelman.org/

Anti-anxiety medications

This group of medications, commonly prescribed for adults, is less often used with children. When prescribed, these medications (also called anxiolytics) are typically employed for brief duration to help manage severe anxiety or to help a youngster through a particularly difficult, time-limited situation.

The group of anti-anxiety medicines described as benzodiazepines (e.g., Valium) act by promoting greater availability of GABA in the brain; they can prove sedating. In contrast, the “atypical” anti-anxiety medications (e.g., BuSpar) appear to work via serotonin rather than GABA; they are believed to be less sedating and less prone to engender dependency. Also, compared to other medications in the anti-anxiety group, BuSpar is sometimes used for longer intervals. Finally, a medication in the class called beta-blockers, Inderal, controls heart rate and blood pressure as well as anxiety (such as fear of public speaking). The table below summarizes information on anti-anxiety medications that school psychologists might encounter.

| Trade name | Generic name | Sub-category | Onset of effect |

| Ativan® | lorazepam | benzodiazepine | Rapid |

| BuSpar® | buspirone | atypical anti-anxiety | Delayed |

| Inderal® | propranolol | beta-blocker | Rapid |

| Klonopin® | clonazepam | benzodiazepine | Rapid |

| Neurotin® | gabapentin | anticonvulsant | Rapid |

| Valium® | diazepam | benzodiazepine | Rapid |

| Xanax® | alprazolam | benzodiazepine | Rapid |

Anti-depressant medications

Although the name suggests that medicines in this group are restricted to treating depression, their use is actually more varied than this. Included are uses for school phobia, panic attacks, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. The tricyclic anti-depressants are also sometimes used to treat bedwetting and ADHD. Each subcategory of anti-depressant typically includes its own side effects profile, such as weight gain for serotonin specific reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), or dry mouth for (tricyclic antidepressants). Some contain stringent dietary restrictions, such as no cheese or chocolate for individuals taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). SSRIs include warnings about elevated suicidal thoughts or actions. The table below summarizes information on anti-depressant medications that school psychologists might encounter.

| Trade name | Generic name | Subcategory | Onset of effect |

| Anafranil® | clomipramine | tricyclic anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Celexa® | citalopram | ‡SSRI | Delayed |

| Cymbalta® | duloxetine | *SNRI | Delayed |

| Desyrel® | trazodone | atypical anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Effexor® | venlafaxine | *SNRI | Delayed |

| Elavil® | amitriptyline | tricyclic anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Fetzim® | levomilnacipran | *SNRI | Delayed |

| Lexapro® | escitalopram | ‡SSRI | Delayed |

| Luvox® | fluvoxamine | ‡SSRI | Delayed |

| Nardil® | phenelzine | †MAOI | Delayed |

| Pamelor® | nortriptyline | tricyclic anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Parnate® | tranylcypromine | †MAOI | Delayed |

| Paxil® | paroxetine | ‡SSRI | Delayed |

| Pristiq® | desvenlafaxine | *SNRI | Delayed |

| Prozac® | fluoxetine | ‡SSRI | Delayed |

| Remeron® | mirtazapine | atypical anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Serzone® | nefazodone | atypical anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Tofranil® | imipramine | tricyclic anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Trintelli® | vortioxetine | serotonin modular | Delayed |

| Viibyrd® | vilazodone | ‡SSRI | Delayed |

| Wellbutrin® | bupropion | atypical anti-depressant | Delayed |

| Zoloft® | sertraline | ‡SSRI | Delayed |

| ‡SSRI = Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; *SNRI = Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; †MAOI = Monoamine oxidase inhibitor | |||

Anti-psychotic medications

The so-called “typical” anti-psychotic medications were developed, as their name implies, to treat symptoms of psychosis. Their development in the 1950’s permitted many hospitalized adult patients with schizophrenia to leave institutionalized care. Unfortunately, the typical anti-psychotics exerted an influence largely confined to positive symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., hallucination, delusion). Practically speaking, this meant that many patients remained impaired because of persistent negative symptoms of schizophrenia, such as lack of initiative or inability to formulate or carry out a plan to aid themselves in daily life. When the “atypical” antipsychotics were developed in the 1980s, the situation often improved because they targeted negative symptoms often left untouched by the older typical anti-psychotics. Much of the initial use of both typical and atypical anti-psychotic medications, however, concerned adults.

Critical to school psychology practice, sometimes atypical anti-psychotics are now used for nonpsychotic youth expressing frontal lobe and executive impairments. Thus, use of atypical antipsychotics has grown dramatically in the practice of child psychiatry. For example, atypical antipsychotics are sometimes used to diminish explosive outbursts in children who seem to suffer extreme problems with impulse control.

There are other uses of anti-psychotics besides the treatment of schizophrenia or overt psychosis. For example, older typical anti-psychotic medications (e.g., Haldol) are sometimes used to reduce severe tics in cases of Tourette syndrome. Both typical and atypical anti-psychotics carry risk profiles, such as development of severe motor problems late in the cycle of treatment (so-called tardive dyskinesia). The table below summarizes information on anti-psychotic medications that school psychologists might encounter.

| Trade name | Generic name | Sub-category | Onset of effect |

| Abilify® | aripiprazole | atypical | Delayed |

| Catplyta® | lumateperone | atypical | Delayed |

| Clozaril® | clozapine | atypical | Delayed |

| Fanapt® | iloperidone | atypical | Delayed |

| Geodon® | ziprasidone | atypical | Delayed |

| Haldol® | haloperidol | typical | Delayed |

| Invega® | paliperidone | atypical | Delayed |

| Latuda® | lurasidon | atypical | Delayed |

| Mellaril® | thioridazine | typical | Delayed |

| Navane® | thiothixene | typical | Delayed |

| Prolixin® | fluphenazine | typical | Delayed |

| Rexulti® | brexpiprazole | atypical | Delayed |

| Risperdal® | risperidone | atypical | Delayed |

| Saphris® | asenapine | atypical | Delayed |

| Seroquel® | quetiapine | atypical | Delayed |

| Stelazine® | trifluperazine | typical | Delayed |

| Thorazine® | chlorpromazine | typical | Delayed |

| Vraylar® | cariprazine | atypical | Delayed |

| Zyprexa® | olanzapine | atypical | Delayed |

Anxiolytics (see anti-anxiety medications)

Apgar score

School psychologists may see Apgar scores listed in students’ medical/developmental records. The score is named for Virginia Apgar, an obstetrical anesthesiologist. It represents a quick test often performed after birth by medical professionals. Typically, two scores are reported (e.g., 7/9 or 9/10), the first indicating the sum of values across five dimensions at one minute following birth, the second at five minutes following birth. The dimensions listed below are used to generate a 0-10 scale.

- Breathing effort (2, 1, 0)

- Heart rate (2, 1, 0)

- Muscle tone (2, 1, 0)

- Reflexes (2, 1, 0)

- Skin color (2, 1, 0)

These are relevant because higher Apgar scores indicate the newborn more easily adjusted to life outside the womb; scores of 7, 8 or 9 denote good health. Perhaps contrary to intuition, the scores are not designed to predict later learning and developmental problems. Nonetheless, low Apgar scores are associated with some negative outcomes (Valla, Birkeland, Hofoss, & Slinning, 2017), such as poor development of communication skills. Also see entries for low birth weight and for preterm birth.

For additional information from the American Academy of Pediatrics, see the following link: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/136/4/819

Aptitude x treatment interaction

An intuitively plausible idea that remains contentious many years after it was first widely discussed (Snow, 1989). One variation of the idea is that students’ individual differences in learning style (aptitude differences) may affect learning such as that one curriculum (treatment) works better for one style than another. If this were true, teachers could use this information to plan for individual students, especially those with SLD. Simply put, a teacher could match a student’s learning style to a complementary teaching approach. For example, visual learners might receive instruction with lots of charts, graphs, and they might read texts silently and try to visualize the content of passages to aid understanding and retention. In contrast, auditory learners might receive lectures and oral discussion to maximize their understanding and retention. Because students with SLD presumably express information processing weaknesses (to be avoided) and strengths (to be capitalized on) this approach garners considerable intuitive appeal. But matching students and instruction in a manner like this (sometimes referred to as tailoring instruction to a modality preference) has long been criticized (e.g., Kavale & Forness, 1999). Problems include technical limitations in reliably detecting a student’s preferred modality and a dearth of controlled studies supporting the practice.

Moving from special needs students to large samples of typical learners, researchers have sought interactions when style is matched to instructional approach. In some experimental studies this is referred to as “meshing.” In general, it appears that results are not favorable. For example, one study that used adult learners characterized as either preferring “visual learning style” or “auditory learning style” detected no benefit when learning style was used to guide instruction. That is, the visual group’s anticipated advantage when given e-books and the auditory group’s anticipated advantage when given audiobooks failed to eventuate (Rogowsky, Calhoun & Tallal, 2015).

On the other hand, some genuine aptitude X treatment interaction effects have been reported when students’ levels on a dimension (e.g., above average working memory vs. average or lower working memory) is used as the aptitude variable. This is exemplified in a study by Fuchs et al. (2014) that found working memory level interacted with instructional approach when teaching at-risk students an aspect of arithmetic (i.e., fractions). Specifically, one teaching method (aimed at building fluency) was found better for students toward the low end of the working memory continuum, whereas another teaching method (aimed to consolidate understanding) was found better for students who possessed more fully developed working memory.

Arithmetic (computational) terminology

In speaking with teachers, it is sometimes important to be conversant in instructional terminology. The figure below provides a few terms pertaining to elementary computational arithmetic.

Examples of arithmetic terminology (terms in parentheses)

7 (“addend”) + 7 (“addend”) = 14 (“sum”)

8 (“minuend”) – 2 (“subtrahend”) = 6 (“difference”)

36 (“dividend”) ÷ 6 (“divisor”) = 6 (“quotient”)

÷9 (“factor”) X 6 (“factor”) = 54 (“product”)

Ascertainment bias

Refers to a type of bias that threatens the validity of psychological or educational research findings. Specifically, ascertainment bias exists when participant recruitment creates a non-representative sample (when in fact representativeness is crucial). For example, assume researchers are interested in how often students with reading problems also experience clinical levels of depression. Carelessly, these researchers post a recruiting poster in a reading clinic that says: “Sign up your child for an important study of reading and depression.” Obviously, parents of depressed children might be more likely to enroll their youngsters than are parents in general. Now when researchers compare depression rates among youth with reading problems and youth in general (the latter being a random control sample) erroneous inferences are a real risk. In this case the biased sample of readers may over-express how strongly reading problems and depression co-exist. This is an important consideration for school psychologists because many quasi-experimental studies (those comparing a clinical group with a control group) suffer ascertainment bias. The solution to such problems is for researchers to, for example, recruit consecutive cases and report in their published findings detailed information about participant recruitment (often they do not). The solution for practicing school psychologists is to be vigilant when reading studies comparing youth with and without a particular clinical condition.

Assistive technology (AT)

For school psychologists, mostly relevant in planning for and assisting students with special needs. A variety of procedures, many of which are electronic in nature, have been used to support students and circumvent barriers to learning. AT applications range from helping students with severe cognitive impairments to supporting college students with circumscribed learning disabilities. For example, a recent survey and meta-analysis of AT that concerned adolescents/adults with specific learning disabilities is summarized in Table 1 (Perelmutter, McGregor & Gordon, 2017).

Research has also addressed AT applications to youth with intellectual disabilities. A review (Mechling, 2007), for example, found that AT had the ability to aid the initiation and execution of daily tasks. Some aspects of AT were electronic (e.g., computer-aided systems), whereas others were much more low-tech in nature (e.g., pictorial or auditory prompts). Because they are located on school campuses, school psychologists can sometimes observe first-hand which AT works best for which student (as opposed to adopting a one-size-fits-all approach).

|

Effect of assistive technology on adolescent and adult functioning

|

|||

| Nature of device | Exemplar commercial products used | Dependent variables | Magnitude of effect |

| Text to speech | Kruzweil 3000®, ClassMate Reader®, Bookwise® | Reading comprehension | Moderate |

| Speech to text | DragonDictate®, IBM VoiceType® | Variety on variables | Moderate to large |

| Word processing (with spell/grammar check) | Modern word processing programs | Error rate | Large |

| Multi-media (e.g., hyper-text) | N/A | Variety of variables | Small to large |

| Smart pen | LiveScribe®, Quicktionary® | Reading comprehension | Moderate |

| Modified from Perelmutter, McGregor and Gordon (2017) | |||

Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB)

An organization that is responsible for the licensure and certification of psychologists across the United States and Canada. Among ASPPB’s tasks are development and implementation of the psychology license exam entitled the Examination for Professional Practice in Psychology (EPPP). EPPP is a vehicle for licensure among doctoral level psychologists, only a relatively few of whom practice in schools.

For more information see the following link from ASPPB: http://www.asppb.net/?page=What_is_ASPPB

Asthma

Asthma is one of the most common childhood illnesses. It ranges in severity from mild and intermittent, which is typically treated by primary care physicians, to chronic, severe, and life altering, and thus often treated by pediatric pulmonologists or allergists. Individuals with asthma experience periodic, or sometimes chronic, inflammation and thickening of the airways. Breathing becomes difficult and the child may feel uncomfortable. For some, sleep becomes problematic. Asthma-related deaths occur occasionally. Not surprisingly, some students with asthma suffer illness-related school problems. These include difficulty focusing and concentrating because of concern about their breathing, occasionally medication side effects, rarely (but important when it occurs) hypoxia (i.e., low oxygen levels in the blood stream). School absenteeism may be a problem.

Because of concern about the effects of asthma on youth, the National Institutes of Health has recommended educational programs that extend into communities and their schools. One such program that enjoys empirical support is entitled Staying Healthy-Asthma Responsible & Prepared. This program blends information about biology, psychology, and sociology with school subjects such as spelling, math and reading. Students who participated in this program have shown improved knowledge and reasoning over students enrolled in a non-academic program about asthma (Kintner et al., 2015).

The following link from the Centers for Disease Control offers strategies for addressing asthma school: https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/pdfs/strategies_for_addressing_asthma_in_schools_508.pdf

Ativan® (see anti-anxiety medications)

Attending physician (see psychiatric hospitalization)

Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)-authority to make diagnosis

Diagnostic authority regarding ADHD is controversial and without a clear consensus. The National Institute of Health (NIH) suggests it be done by a licensed professional. Interestingly, however, NIH enumerates physicians, psychologists, and social workers as candidates to do so, as long as they possess experience in ADHD. This is important because NIH fails to mandate that the diagnosis be made by physicians, contrary to what school psychologists might hear in their school setting.

Critically, because licensing is handled at the state level, local licensing and authority provisions determine who is legally authorized to make diagnoses like ADHD outside of schools. That said, research (Viser et al, 2015) suggests that school personnel assign ADHD diagnosis in only about 2.8% of cases. In contrast, more than 50% of the time diagnoses are assigned by primary care physicians, such as pediatricians or family practitioners. Non-school-based psychologists (e.g., licensed psychologists in private offices) make school-age ADHD determinations in about one in seven cases.

More details are available at the following link: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr081.pdf).

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)-obligation to identify and provide 504 Services

Perhaps some of the longstanding uncertainty and ambiguity about qualifying students with ADHD for services under Section 504 of the Americans with Disability Act was recently diminished. The source of clarification was a July 2016 letter from the Office of Civil Rights entitled “Dear Colleague.” Its intended audience was school districts, including professionals employed there. This is important because there is much misinformation about students with ADHD and the role of their schools in identifying and helping them. The following points were made in this letter

- A school district must evaluate students who are suspected of having any kind of disability in all specific or all related areas of education need, even if the students do not fit into one suspected disability category or fit into multiple disability categories. (p. 18)

- It is the district’s obligation to evaluate; it cannot shift the burden of that cost or obligation onto the parent. (p. 19)

- ….concentrating…..is [itself] a major life activity (as required for Section 504 designation)

- “OCR [Office of Civil Rights] will presume, unless there is evidence to the contrary, that a student with a diagnosis of ADHD is substantially limited in one or more major life activities.” (p. 10)

- “Mitigating measures [medications, coping strategies] shall not be considered in determining whether an individual has a disability.” (p. 5)

- The requirement to provide a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE), as required by Section 504 as well as IDEA, can be insured by the creation of an IEP (IEPs are not restricted to special education students).

- Plans often fail at the implementation level, which violates the FAPE requirement.

- If the district suspects that a student has a disability….it would be a violation of Section 504 to delay the evaluation in order to first implement an intervention…. (p. 17)

- It is important that school districts appropriately train their teachers and staff to identify academic and behavioral challenges that may be due to a disability so a student is referred for an evaluation under Section 504….(p.17)

- …there is nothing in Section 504 that requires a medical assessment as a precondition to the district’s determination that the student has a disability (p. 23).

A link to the entire document follows: https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201607-504-adhd.pdf

Audiometer

A device used to determine the hearing level of individuals. In schools, audiometers are often used to screen all students as well as part of selective, in-depth assessments conducted by audiologists.

Auras (related to seizures)

Refers to a sensation (perception) near the start of a seizure. Auras may range from specific sensations to generalized feelings. They occur only in some individuals with epilepsy. For other students, auras may also appear as a prelude to a migraine headache.

Autism (Autism Spectrum Disorder)-diagnostic considerations

School psychologists are often involved in eligibility decisions for students suspected of autism. Note: “autism” is one of the 14 categories of IDEA, and schools have an obligation to identify students with autism who need special education and related services. Because most school psychologists are less familiar with autism eligibility than with SLD eligibility, they may be unsure as they proceed. Consequently, they are encouraged to remember to practice ethically and in the best interest of the student.

First, a psychometric test is mandatory to establish eligibility. For example, both IDEA and DSM-5 list criteria for autism (or autism spectrum disorder [ASD]) and each criterion can be confirmed (or disconfirmed) by the things that school psychologists routinely do in practice: observe, interview, review records, speak with parents, speak with teachers. As an aside, a criterion-by-criterion examination of IDEA’s autism and DSM-5’s ASD criteria shows that the two are virtually identical (DSM-5 is a bit more stringent and it contains many more details). Although formal instruments are not required, there are many rating scales (and at least one test-like procedure) that can add value to the diagnostic process. This is true because these instruments afford known (and often favorable) diagnostic utility statistics (sensitivity and specificity). These include: the Autism Spectrum Rating Scale (Goldstein & Naglieri, 2013), the Childhood Autism Rating Scale-Revised (Schopler, Van Bourgondien, Wellman, & Love, 2010) the Autism Diagnostic Observation System-2 (ADOS-2, which has a test-like format; Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, & Risi, Gotham & Bishop, 2012).

Second, diagnosis and planning for students with autism requires prior experience. This is commonsense and it is also reflected in professional standards concerning autism diagnosis (e.g., the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society, see link at the end of this section). For practitioners who seldom see students with autism, or for beginning practitioners encountering their first such cases, mentoring by a senior colleague who shares in the decision-making process makes good sense.

Third, intellectual disability (ID) is a marked risk for all students with autism. IQ and adaptive testing are sometimes required to rule out this possibility (in other cases timely acquisition of developmental milestones or evidence of academic success are sufficient to rule out ID).

Fourth, in the presence of intellectual disability and/or autism, practice guidelines suggest the need for medical input. This is because medical etiology for each of these conditions can often be established (e.g., more than 50% of the time). Not infrequently, the cause turns out to be a condition that is potentially preventable in subsequent pregnancies. For example, students with autism spectrum disorder and fragile X syndrome signify a 50% risk that males subsequently born to the same parents will also suffer fragile X syndrome. Intellectual disabilities associated with lead ingestion or fetal alcohol syndrome prompt considerations about prevention. Unfortunately, research suggests that school psychologists are often reluctant to think about medical etiology (Wodrich, Tarbox, Gorin, & Balles, 2010). In light of all of these facts, when school psychologists and their school teams establish the presence of autism, a copy of their report, with “autism” highlighted, is often send to the child’s primary care physician (after parents sign a release form).

The American Academy of Neurology guidelines on screening and diagnosis of autism are available at the following link:

Autism (federal) definition

The IDEA definition of autism is as follows: Autism means a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction, generally evident before age three, that adversely affects a child’s educational performance. Other characteristics often associated with autism are engagement in repetitive activities and stereotyped movements, resistance to environmental change or change in daily routines, and unusual responses to sensory experiences. Autism does not apply if a child’s educational performance is adversely affected primarily because the child has an emotional disturbance, as defined in paragraph (c)(4) of this section. A child who manifests the characteristics of autism after age three could be identified as having autism if the criteria in paragraph (c)(1)(i) of this section are satisfied.

See the following link: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8/c

Autism (Autism Spectrum Disorder)-treatments

A surprising array of treatments are sometimes advocated for children with autism. School psychologists, of course, are most familiar with special education (e.g., special class placements, resource services) and related services (speech-language, applied behavior analysis). School psychologists can familiarize themselves with the type of services available and the empirical support for each.

For starters, they may wish to consider the following link from the National Institutes of Health: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/conditioninfo/treatments

Basal readers-basal reading series

This refers to a series of reading textbooks that are integrated across grade levels. School districts typically adopt a single basal reading series comprising stories with increasingly complex vocabulary, nuanced content, and challenging comprehension requirements. For most series, extensive instructional and support material is provided for teachers by the series publisher. As one might suspect, these reading programs are carefully constructed to teach component skills and provide sufficient practice to develop competent readers among most of the school population. Recognition of basal reading series is important for school psychologists because districts vary in their practices for disabled readers. In some school districts, for example, special education reading instruction must continue to use basal readers exclusively, whereas in other settings clinical reading programs, supplemental material, or alternative approaches are routinely used. These may even replace the district’s basal series for some special needs students.

Base rate

The rate of occurrence of a particular condition in a particular setting (sometimes also referred to as the local prevalence rate). Base rates can be used in Bayesian analyses where they are treated as pretest probabilities.

Bayesian (probability) nomogram

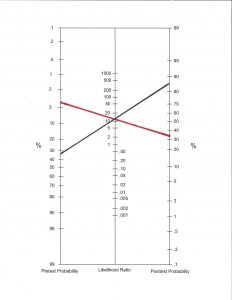

A graphical method of determining (or at least estimating) the probability that a particular condition (e.g., autism, ADHD) is present based on existing diagnostic information. This procedure has the advantage of systematically updating probability as additional sources of diagnostic information are added. Use of a nomogram is said to be Bayesian because the procedure rests on Bayes law. Although Bayes’ law is expressed in a mathematical formula it can also be summarized verbally. Simply put, any test’s predictive value when positive is equal to its sensitivity multiplied by its base rate divided by the percentage of those who test positive. To preclude the need to plug numbers into a formula and make calculations, a simple chart (a nomogram) can do the work.

Typically, several steps are involved in using a nomogram. The first is entering a known, or estimated, base rate of the condition under consideration (sometimes called a local prevalence rate). This value is specific to the local setting in which a diagnostician finds herself. It assumes that preliminary work has been done so that base rate information is known regarding a particular condition. For example, pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD) is confirmed to occur at different rates in different practice settings. This is known because practitioners have kept track of occurrence rates at their sites over a period of months or years. To illustrate, the PBD general population prevalence rate is approximately .006 among general high school students. In contrast, the base rate has been found to be .02 among adolescents at an incarceration center, .06 at a general outpatient clinic and .30 among adolescents in a psychiatric hospital (Youngstrom, 2007). Base rate information proves to be vitally important for judgments about the presence of PBD. Base rate values (or other prior probability information) is entered into the left column of the nonogram.

The next step requires accessing a relative risk, which is expressed as a ratio (see separate entry) or a diagnostic likelihood ratio (see separate entry). Either of these indicates how much more likely a particular diagnosis (e.g., PBD) exists among youth in a select group (e.g., individuals with a certain co-morbid condition, with scores above a cut-off value) than among youth in general. The nomogram permits this second value to be combined with the first (base rate) value to reach an updated (posttest) probability. For example, assume the base rate for autism among elementary students undergoing psychoeducational evaluations is .04 in District A. Also assume that a diagnostician uses the Autism Diagnostic Rating Scale (ASRS; Goldstein & Naglieri, 2013) and accesses sensitivity and specificity information in the ASRS manual. It is possible for her to calculate a DLR, which turns out to be 11.2 for this test concerning this diagnosis. She can then apply the ASRS’s DLR of 11.2 to the nomogram’s second column. A line connecting the two columns shows that there is a revised probability of autism, based on just those two pieces of information, between .30 and 40%. Contrast this with District B where the autism base rate has been found to be much higher, say .35. A diagnostician in District B goes through the same steps using the nomogram but a vastly different posttest probability eventuates. In District B, ASRS’s DLR (11.2) results in a post-test probability of more than .85. These are depicted in the accompanying figure by the red and black lines, respectively. For clinical-like use of Bayesian nomogram procedures school psychologists need additional details, practice, and guidance. To that end, extensive information, including blank nomogram forms, is available at the website of Eric Youngstrom at the University of North Carolina. http://ericyoungstrom.web.unc.edu

It appears that school psychologists are beginning to hear about application of the nomogram to their practice. Examples include applications in detecting SLD via score scatter on the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children-II (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004). Unfortunately, Bayesian nomogram procedures failed to aid in SLD detection regardless of the degree of subtest scatter (McGill, 2017). In contrast, the nomogram procedures worked when detecting ADHD. Specifically, scores from a screening test (the Pediatric Attention Disorders Diagnostic Screener) appear to offer assistance depending on the local base rate and students’ scores (Keiser & Reddy, 2013).

Behavior Bingo (see group contingency interventions)

Behavior intervention plan (BIP)

A formulated plan, often detailed in written form, designed to promote behavior change. BIPs often identify one or more problematic behaviors to be diminished in parallel with one or more positive opposites to be promoted.

Behavior plan failure (how to troubleshoot)

School psychologists often consult with teachers (or parents) to devise behavior intervention plans (BIPs). Unfortunately, even the best BIPs sometimes fall short. There are several things that school psychologists might do to improve the prospect that their plan works. Asking oneself these questions is one way to troubleshoot.

- Is the target behavior actually in the child’s current response repertoire? If it isn’t, it may help to consider shaping.It is a common error to expect the child to execute behavior beyond his/her capability. Consider revising the BIP to demand simplified behavior or break down complex behavior into small components. In other words, consider using the principle of successive approximations.

- Is the reinforcement sufficiently strong? In token economies, for example, the cost of back-up reinforcers is sometimes set too high. Students may simply lack motivation at the trade-in value currently set. Similarly, in traditional contingency management systems, weak reinforcers (e.g., 10 minutes of computer time) contingent on extensive execution of target behavior (e.g., 2 hours of sustained homework completion) might be destined to fail.

- Is reinforcement delivered promptly? Delays between the student’s target behavior and delivery of reinforcement diminishes reinforcement potency. Sometimes it helps to shrink timelines; completing homework on Monday for a Friday evening privilege may doom a BIP.

- Is the program implemented with integrity? Among the most common limitations of BIPs is that their elements are not really followed. It can help to monitor how teachers and parents are going about putting the plan into effect. The same is true regarding making sure that stakeholders are actually invested in a BIP’s success. It may be necessary to re-teach and re-motivate those who are implementing the plan.

Benzodiazepines (see anti-anxiety medications)

Bili lights (see neonatal jaundice)

Bladder incontinence (see enuresis)

Bowel incontinence (see encopresis)

Broadband scales (also narrowband scales)

Refers to behavioral rating scales designed to cast a broad net for the detection of psychopathology and related problems. For example, the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Third Edition (BASC-3; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015), includes a broad measure of psychopathology (the Behavioral Symptom Index), slightly narrower indices of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, and many still-narrower scales corresponding to specific emotional-behavior problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, attention problems). Scales like this are especially important for school psychologists when they may lack refined hypotheses about the nature of a particular child’s potential emotional-behavioral problem(s) or when they simply seek to screen across various dimensions. Consequently, such scales are quite popular, the BASC-3 version for teachers, for example, representing the most frequently used of all psychological assessment tools (Benson, Floyd, Kranzler, Eckert, Fefer & Morgan, 2019).

Bruxism

Non-functional (i.e., purposeless) grinding or clenching of the teeth. Nocturnal bruxism is far more common than bruxism occurring when a child is awake. The literature reports rates from roughly 6% to nearly 50% of youngsters (Machado, Dal-Fabbro, Cunali, & Kasier, 2014). Although causes are unknown, dental problems (e.g., poor alignment of teeth) and psychological factors (e.g., stress) are implicated. Complaints of headache or earache may accompany bruxism. Chronic bruxism among awake children may be associated with developmental delay and/or pervasive neurological disorders or (more rarely) tics or obsessive-compulsive disorder. To avoid progressive tooth damage and promote quality of life, ongoing dental care is often important. Thus, school psychologists sometimes play advocacy roles when they encounter students with bruxism.

For more information see the following link at the American Academy of Pediatrics website:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/131/3/614#xref-ref-18-1

Buros Center for Testing

A potentially important site for school psychologists that offers classic (in print) resources such as the Mental Measurement Yearbook and Tests in Print. Probably more relevant for contemporary practitioners, the center also publishes online reviews and critiques of tests likely to be encountered in practice. More information is available at the following link:

http://buros.org/test-reviews-information.

BuSpar® (see anti-anxiety medications)