C. Intro to Corpus Analysis

Robert Poole

This module is helpful for learners who want to know more about a corpus analytic approach to language use and critical discourse analysis. We recommend doing it if you are going to do the corpus analysis activities.

Situating questions for discussion and reflection

- What things would you describe with one word as opposed to its synonym? What differences are there in meaning? For example, ‘little’ as opposed to ‘small’ when describing ‘boy’ or ‘man’? ‘weird’ as opposed to ‘odd’ when describing ‘trick’ or ‘person’?

- What buzzwords do you think a certain politician may use more frequently than other politicians, and for what reasons? For example, ‘freedom’, ‘we/us/our/ours’, ‘struggle’, ‘patriot’, or ‘justice’?

- What are some words that you would only use in academic writing and not in casual conversation, and vice-versa? Why is this the case?

- How has the meaning and frequency of usage of certain words changed over time? For example, ‘cool’, ‘groovy’, ‘gay’, ‘wicked’, ‘bro’?

- How did you know or intuit answers to the above questions? How much do you trust your experience or intuition? How could you find answers if you wanted to explore these questions?

C1. What is a corpus?

A corpus is a large, searchable, (often) annotated collection of authentic language use that is collected in a principled manner to be representative of language from a certain domain. This definition has some keywords deserving elaboration. Let’s explore each in turn:

- Large: In the 1960s, the first modern corpus—the Brown Corpus—contained approximately 1 million words representing 15 written genres. Today, perhaps the most widely used corpus is the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) with 1 billion words drawn from registers such as film and television, blogs, fiction, magazines, newspaper, and more. Yet, 1 billion words does not make the COCA the largest public corpus. For example, the iWeb corpus contains nearly 15 billion words while the Google Books Corpus is greater than 150 billion words.

- Searchable: A corpus of such size as previously mentioned would not be useful if it were not easily searchable. The various search functions made available at public corpora such as the COCA and that are embedded in corpus tools such as Antconc enable researchers, teachers, and students to collect information about certain words, see the contexts in which words are used, examine how the use of a word has changed, and much more. For example, one could quickly do a search to discover whether figure out or discover is used more frequently in academic writing, which adjectives are most commonly used with the noun immigrant, which tense of verb most often appears with subordinating conjunctions when and while, and much more.

- Annotated: A feature of corpora that allows for such search potential is the fact that most corpora are annotated. The most common form of annotation is a part-of-speech (POS) tag. This means that in the COCA, for example, each of the 1 billion words has been annotated with a POS tag, thereby adding to the search capabilities of the collection. For example, one may want to determine which are the most common nouns following the near-synonyms beautiful and attractive or the most frequent verbs used with the adverbs broadly and largely. Additionally, one may want to search for only examples of when cook is used as a noun, excluding instances where it appears as a verb. While there are other types of annotations that can be added, for our purposes, POS tags are the most relevant and important.

- Authentic: Though authentic is fourth on this list, it is possibly the most important feature of a corpus. Why is authenticity so important? Before the development of corpora, people made claims about language use based primarily on their intuition alone. The problem is intuition is limited and generally inaccurate. Though we may think we know how a word or grammar item is used, research has shown again and again that our intuitions about language use are often incorrect. One reason is researchers could only base their statements about the use of the subjunctive, the frequencies of who or whom, the functions of modals such as may, might, or could on their individual experiences with language. Thus, they could only formulate claims about language use based on their own limited experience with language. A middle-aged linguistics professor may think a word or phrase is used commonly, but they only know what is used in their small community. This limitation had consequences in all sorts of areas. For example, though less common today, the language presented in textbooks for language learners often felt dated and/or artificial. Today, textbook writers can use corpora when creating materials, allowing them to include the actual language that speakers/writers use.

- Principled and representative: Though there are some technical distinctions concerning these two items, we can combine them for our purposes. These terms indicate that corpora are meticulously designed and created so that users can be certain that their corpus findings are accurate and relevant to their question. For instance, if one wanted to analyze the use of adverbs such as probably, likely, and clearly in legal writing, they would need to have a principled plan to collect texts. Should they include briefs written by lawyers, opinions published by judges, legal textbooks written by law professors, or medical reports written by physicians? Obviously, you would not include medical reports, but depending on the focus of the analysis, you might also want to exclude textbooks too. If you decide to use a corpus, you should first determine what sort of texts are actually in the corpus. Corpus designers make this information available so that others can verify that the corpus was carefully designed to be representative of a certain genre or register of language use.

C2. What does corpus study make possible?

The applications of corpus study are numerous, and the previous section highlighted several. Their primary application is that they allow us, whether language researcher, textbook creator, language teacher, or language learner, to gain insights into the actual language that people use. Rather than responding to a question about language with disclaimers such as “Well, I think that…” or “I feel that…”, we can simply go to a corpus and find the answer. When we then go to the corpus for the answer, we are able to see numerous examples of how people indeed use a word, grammar item, or phrase. This allows textbook writers and language teachers to present accurate information to readers and learners.

Additionally, corpus study allows us to see things about language use of which we were not previously aware. For example, by analyzing corpora, we have learned that language is rather formulaic, meaning we use lots of “chunks” when we speak and write. Yes, we are aware of “chunks” such as ‘on the other hand’, ‘a result of’, and ‘I don’t know if’, but corpus study has revealed how these “chunks” are the building blocks of language. In other words, we do not necessarily learn and mentally store individual words that we later retrieve one by one to build a sentence; rather, we learn, store, and use “chunks” of language. Corpus study shows us too that the “chunks” I use in one genre or register are different than the “chunks” I use in other genres and registers.

And finally, and related to the previous items, corpus study allows us to see patterns in language use of which we may be unconscious but that function to shape our perceptions of and relationships with the world around us. Considering our goal to develop critical language awareness, this is quite powerful. The popular notion suggests that language use is somehow natural and that it simply captures and reflects objective facts about the world. However, the language choices we make do not capture an existing reality but build one for us. Language use and choice are not given; they are purposeful and subjective. For example, there is nothing inherently natural about the pairing illegal immigrant. As Holocaust survivor and Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel states, “No human is illegal”. If I instead choose to use undocumented immigrant, I am building a different sort of world. As Carbaugh states, the choice we make is “a symbolic move within a cultural game, a move which creatively evokes a complex of associations, and invites one’s interlocutor into a discursive space from which we see, hear, feel, and act” in certain ways. In the case of undocumented/illegal immigrant, the selection of the attributive adjective influences how we think and ultimately act. For a grammar-oriented example, if I use the passive construction “Mistakes were made”, I have selectively chosen to hide who actually made the mistake. The passive is quite different than the active voice alternative: “I made a mistake”. If we consider how this may be manipulated for certain ends, consider the following samples from the News on the Web (NOW) Corpus collected from reporting following the May, 2022 killing of journalist Shireen Abu Akleh:

- Israeli police clashed with Palestinian mourners packed around the coffin of killed Al Jazeera reporter Shireen Abu Akleh (Reuters, May 13, 2022)

- 13 Palestinians were wounded in the clashes, one of them seriously. (MSN.com, May 13, 2022)

- More than 40 Palestinians were injured in renewed clashes at the Al-Aqsa Mosque on Friday (Forbes, May 13, 2022)

These instances demonstrate how the selection of verb forms can either foreground, background, or even remove agents and obscure the reality of the events. The selection of a certain pattern is not altogether arbitrary for it captures and reflects one’s perception of the event. In the first sample, the agent (Israeli police) responsible for the action is explicitly named in the subject noun phrase of the sentence. The placement of Israeli police in this initial and prominent position serves to essentially assign responsibility for an action/event. However, in samples 2 and 3, the agent is removed from the sentences through the passive verb construction. In both sentences, the affected is clearly named but the agent responsible for wounds and injuries is not identified. While that information can likely be retrieved from elsewhere in the article, it is revealing that the person/group responsible for the injuries is removed. As these authentic samples illustrate, grammar, in this case the passive verb phrase, allows speaker/writers to package information in ways which influence the interpretation and understanding of readers and listeners. Throughout the modules, we will see examples where the grammar we use is a powerful tool for informing, misinforming, and obscuring in order to persuade listeners and readers to build a certain view of the world.

C3. How does one search a corpus?

Though the activities throughout the modules do not require you to be an expert in corpus linguistics, it will nonetheless be useful for you to understand how to do basic searches within an online corpus. By gaining such skills, you will be able to verify claims about language use and complete corpus activities throughout the modules. Most importantly, you will be able to explore language use of interest to you. In this section, we will explore the 6 primary search options of the COCA. While the functions are demonstrated using the COCA, these basic search options are present in most available corpora.

First, go to https://www.english-corpora.org. You will need to register to use the corpora on the site, but it is free and only takes a moment. Once registered, select “Corpus of Contemporary American English” from the list of available corpora.

a. list

The first search option is rather simple, but we will add a few techniques to increase its power. As we have previously discussed immigrant and immigration, we will use these words to demonstrate the various search functions in COCA.

C1. Frequency

How many times is the word immigrant used in the corpus?

- Click list from the options above the search bar.

- Enter immigrant in the search bar.

- Click find matching strings

C2. Wildcard

What are the various forms of the word immigrant, immigration, etc.?

- Enter immigra* in the search bar

- Click find matching strings

The output produced by the use of the wildcard is quite useful for it allows us to view many forms of our search word. In this instance, the search allowed us to capture all words beginning with immigra. We can use the wildcard in many positions to enhance our searches. For example, we could search *tion to explore all words ending in tion. The wildcard can also fill a slot in a phrase. For instance, we could search “the * of immigration” to determine which words are used to frame immigration.

C3. Verb forms

What are the various forms of the verb immigrate?

- Enter [immigrate] in the search bar

- Click find matching strings

The bracket search is most useful for exploring forms of a particular verb. For example, [take] yields the frequencies of take, takes, took, taking, taken and also takin.

C4. Synonyms

What are synonyms of immigrate?

- Enter [=immigrate] in the search bar

- Click find matching strings

Entering the equal sign in the search signals that you would like to explore synonyms of the search word.

b. chart

C5. Searching by register and across time

In what register(s) does immigrant appear most frequently, and in what time period does it appear most frequently?

- Click chart from the search options

- Enter immigrant in the search bar

- Click find matching strings

In the output for this search, you can observe in which register (e.g. magazines, fiction, newspaper, etc.) the word most frequently appears. You can also view its frequency of use across six five-year periods from 1990-2019.

It is important to remember that the previous searches using wildcards, brackets, and the equal sign can all be used with the chart search option as well.

c. word

The word option provides rather comprehensive information about any of the 60,000 most frequently used words in the corpus. If you enter and search immigration, you can get a view of the sort of information provided. For instance, the output displays a chart of the word’s frequency in various registers, the various topics in which it appears, its common collocates, and more.

C6. Exploring ‘immigrant’

What are various features of the word immigrant?

- Click word from the search options

- Enter immigrant in the search bar

- Click see detailed info for word

d. collocates

From our critical orientation, the collocates search is likely the most powerful of the search options, as it allows us to see how a particular word is represented and in which contexts it is most frequently used. Indeed, much research in corpus-assisted discourse analysis analyzes the collocations of keywords, often additionally exploring how a keyword’s collocations have changed over time. When analyzing a word’s collocates, we are aligning with a key corpus linguistics principle: “You shall know a word by the company it keeps”. One way to think about “company” is whether the collocates are generally negative or positive. For example, Tognini-Bonelli demonstrates how the collocates of the near-synonyms largely and broadly are quite distinct. While we intuit these words to be interchangeable, they occur in rather distinct contexts. In this case, broadly frequently appears with positively-loaded adjectives (e.g., similar, applicable, shared, popular, acceptable) while largely occurs with more negative-loading collocates (e.g., responsible, unknown, irrelevant, absent, ineffective). In corpus study, these contextual loadings are referred to as semantic prosody. Let’s search the semantic prosodies of illegal and undocumented.

C7. Exploring ‘illegal’

What are collocates of the word illegal?

- Click word from the search options

- Enter illegal in the search bar

- Click see detailed info for word and note the collocates

C8. Exploring ‘undocumented’

What are collocates of the word undocumented?

- Click word from the search options

- Enter undocumented in the search bar

- Click see detailed info for word and note the collocates

e. compare

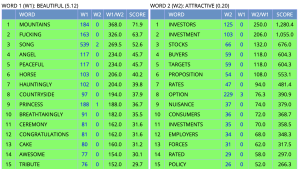

The compare search adds a layer to the collocates function, as it enables you to view collocates for two words at the same time. This function can be quite useful for exploring how two near-synonyms collocates are used differently. Indeed, the function illustrates why the term near-synonym is preferred within linguistics for no words are truly synonymous. To illustrate, consider the adjectives beautiful and attractive. Upon first reflection, it is likely you view these items as synonyms. However, a compare search in a corpus such as the COCA will reveal the rather divergent contexts in which they are used and their connotations. The image below displays the two words collocates; what differences do you note in the connotations of their collocates?

C9. Comparing connotations of collocations

How do the connotations of the collocates of illegal and undocumented compare?

- Click on the + and then Compare from the search options

- Enter illegal in Word1 and undocumented in Word2 in the search bars

- Enter a * in the Collocates bar

- Click Compare Words and note the differences in the positive, neutral, or negative connotations of the collocates for each

f. KWIC (Key Word In Context)

The final function is made possible because the corpus has been annotated for part of speech. The KWIC search is simple function, but it can be quite useful for it assigns a color to each part of speech in the context of the search term. The color coding can help to identify grammatical patterns around the target search word.

C10. ‘immigrant’ in context

What are some grammatical patterns found with the word immigrant?

- Click on the + and then KWIC from the search options

- Enter immigrant in the search bar

- Click on Key Word in Context and note grammatical patterns

Module author: Robert Poole

Last updated: 7 October 2022

This module is part of Critical Language Awareness: Language Power Techniques and English Grammar, an open educational resource offered by the Clarify Initiative, a privately funded project with the goal of raising critical language awareness and media literacy among students of language and throughout society.

an adjective that comes directly before the noun that it modifies, as opposed to a predicative adjective

a form of language use where an object becomes the new subject and the original subject and its agency is deemphasized or omitted

an association or suggestion of a word or idea