4CA. Nouns Corpus Activities

Robert Poole

These corpus analysis activities are designed for the content in 4. Nouns and for use with the Corpus of Contemporary English. If you’re not familiar with the basics, be sure to do C. Introduction to Corpus Analysis first.

⇒ Corpus activity 4.1 Identifying nouns

⇒ Corpus activity 4.1.1 Noun morphology

⇒ Corpus activity 4.1.2 Gerunds

⇒ Corpus activity 4.1.3 Compound nouns

⇒ Corpus activity 4.1.4 Insights into nouns

⇒ Corpus activity 4.2.1 Concrete & abstract nouns in different registers

⇒ Corpus activity 4.2.2 Proper nouns

⇒ Corpus activity 4.2.3 Singular, plural, & collective nouns

- In COCA, search for the word ‘cook’ using the list function. When the results appear, click on ‘cook’ to reveal example sentences. Scan the sentences (ignore instances where Cook appears as a person’s name) and identify five instances where ‘cook’ is used as a noun. What textual cues did you use to help you identify the noun instances of ‘cook’?

- Repeat the process from number 1 but search for the word ‘produce‘.

- For the final task, search for the word ‘professor‘ and view the example sentences which include it. Focusing upon ‘professor’ as the head noun, identify the noun phrase of which it is included using the pronoun test. For example:

-

- Felder is a professor of pathology and associate director of clinical chemistry.

In the example, [a professor of pathology and associate director of clinical chemistry] is the noun phrase.

List 5 noun phrases from the COCA data which include ‘professor’.

⇒ Return to 4.1 What is a noun?

- List five common suffixes used to create nouns.

- Using the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), complete a wildcard search to produce a list of nouns using one the suffixes. List the five most frequently used nouns which use the suffix.(Note: Insert the wildcard * and then add the suffix).

- Again, using the COCA, complete a chart search for one of the nouns you listed above. In which register is the noun used the most? In which is it used the least? How would you explain this variation between the two registers?

- Next, complete a word search. What are the five most common adjectives that collocate with the noun?

- In the COCA, complete a search to compare the frequency of the [ment] suffix between academic and spoken registers of language use. Before doing so, what is your intuition about use of the suffix in the two registers? Will it be used the same in both registers? Now complete the search and evaluate whether your intuition matches actual use. How might you explain the difference in its use?

⇒ Return to 4.1.1 Noun Morphology

As discussed elsewhere, a gerund is lexical item that prototypically functions as a verb (e.g. “The dog is playing with the frisbee”) that is now functioning as a noun or noun phrase (e.g. “Playing with the frisbee is fun for the dog.”). As we learned to identify noun phrases with the pronoun test, we can see that in the first sample, the test fails (“The dog is it with the frisbee“). However, the test works for the second (“It is fun…”). This process by which we take one word class, in this case a verb, and transform it to a noun is called nominalization. In a sense, we have taken the action/process of playing and turned it into a thing/object for us to reflect upon, analyze, and discuss.

In the COCA, let’s complete a search to see which processes (i.e. verbs) are often converted to things (i.e. nouns) in the education section of the academic register. To complete the search, follow the following steps:

- Enter *ing_n in the search bar. Recall that the * will allow us to capture all words that end in -ing while the _n tag allows us to only pull those words that are tagged as nouns in the corpus.

- Click the sections option below the search bar.

- In the first column, scroll down and select ACAD:Education

- Click find matching strings.

Questions:

- In the resulting output, what are the five most common gerunds in ACAD:Education?

- Click on the most frequent gerund (‘learning’) and read several of the sample sentences. What sorts of words surround the gerund that give you clues that it is functioning as a noun?

- Repeat the search to determine common gerunds in a different register of language use. Before completing the search, guess what five gerunds are likely the most frequently used in that specific domain. How many of your guesses match actual language use?

⇒ Return to 4.1.2 Gerunds

- In the COCA, complete a search to discover the most frequently used compound nouns. Use the search syntax NOUN NOUN in the search bar to produce the desired results.

- Next, complete a search to discover the most frequently used adjective + noun combinations. Use the search syntax ADJ NOUN in the search bar to produce the desired results.

- Using the chart function, determine which register (e.g. academic, fiction, magazine, etc.) NOUN NOUN patterns are most common. In which register is the pattern least common? What does the divergence possibly indicate about these two registers?

⇒ Return to 4.1.3 Compound nouns

From the discussion of nouns and noun phrases in 4.1, it may seem that nouns simply identify persons, places, and things or abstract concepts such as love and joy. We could perhaps think that nouns do not do much of the rhetorical work of a text–they just name things, right? However, our selection of a noun within a sentence structure can have significant functional importance to our text, as they enable us as language users to frame an issue in a particular way and to signal our stance on an idea or claim.

Let’s take the case of academic writing. We often consider academic writing to be an objective and author-distant form of writing in which the author simply conveys facts and measurable truths. Yet, recent research in applied linguistics demonstrates quite clearly the persuasive nature of academic writing as authors attempt to gain consensus, convince readers of the validity and importance of their findings, and signal their membership in the academic community. While academic writers may not overtly signal their stances on a particular topic For example, usage-based linguists may indeed believe that Noam Chomsky’s Universal Grammar is flawed and inaccurate. However, they are unlikely to state such opinion explicitly. Instead, they carefully craft arguments that attempt to move their audience to their position. One device academic writers deploy as they do such persuasive work are stance nouns.

Some of the more common stance nouns in academic writing are nouns such as fact, belief, notion, claim, possibility, and idea. A writer/speaker’s selection of one of these particular nouns signals their relationship toward the proposition or entity under discussion. Here’s an example from the journal Applied Linguistics included in Hyland and Jiang’s analysis (2015) of stance nouns in academic writing:

- “Our core argument is based on the fact that processing accounts are usually inexplicit in their relation to representations, but since representations…”

Is this statement about “processing accounts” indeed a fact as the author contends? Perhaps it is. However, if you are inexperienced and lacking knowledge in this space, certainly the framing that fact produces leads you to accept it as such. If the writer were to instead use stance nouns such as belief, notion, or claim, the reader would reach quite different conclusions. This highlights how nouns can function to frame ideas, events, etc. in ways that persuade audiences to reach certain conclusions.

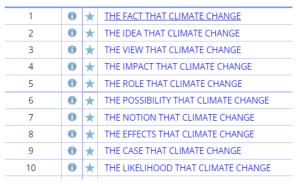

Let’s take the case of climate change in US discourse to further exemplify this point. Climate change remains a controversial topic in the US despite varied, abundant, and compelling scientific data. One reason climate change remains so divisive is the effective work by climate skeptics to propagate the belief that climate science is unsettled. This work occurs through language. The chart below illustrates the order at which stance nouns collocate with the phrase climate change in contemporary US discourse.

Yes, most commonly climate change is framed as a fact, but it also frequently appears with stance nouns idea, view, possibility, and notion. A savvy speaker or writer can manipulate how a topic, in this case climate change, is perceived by selecting a stance noun that frames the issue in their desired manner. In this case, a climate scientist would most likely use the stance noun fact to explicitly indicate their position that climate change is indeed real. In contrast, a climate skeptic would likely select idea, view, or possibility to attempt to demonstrate that climate science remains contested.

So, while we think that other word classes do the bulk of the rhetorical work in a text, do not discount the importance of nouns.

Corpus activity 4.2.1 Concrete and abstract nouns in different registers

- In the COCA, select NOUN.all from the POS menu by the side of the search bar. Once selected, the tag NOUN will appear in the search menu. Click find matching strings. In the output, determine which of the top 10 most frequent nouns are concrete and which are abstract.

- Complete a similar search but focus specifically on the Spoken register. To select Spoken, click on Sections and then scroll to Spoken and click it. Again, determine which of the 10 most frequent nouns are concrete and which are abstract.

- Finally, perform the same search but select Spoken and Fiction. Once you select the registers, choose Sorting below the register options and choose Frequency. How would you characterize the extent of similarity/difference in the two registers preference of nouns? How might you explain the similarity/divergence?

⇒ Return to 4.2.1 Concrete & abstract nouns

- In the COCA, select NOUN.-Prop from the POS menu by the side of the search bar. Once selected, the tag NOUN_nn will appear in the search menu. In Sections below the search bar, scroll and select 1990-1994. Note 10 frequent nouns that seem to typify the discourse of the period. In other words, what were the topics people were talking and writing about in 1990-1994.

- Complete the same steps as the previous search but select 2015-2019 as the time period. What are 10 frequent nouns that reflect the topics people were speaking and writing about in 2015-2019? How do they compare to 1990-1994?

⇒ Return to 4.2.2 Proper nouns

In the COCA, select NOUN.all from the POS menu by the side of the search bar. Once selected, the tag NOUN will appear in the search menu. Also, select TV/Movies from the options. In the output, determine which of the top 20 most frequent nouns are singular, plural, or collective.

⇒ Return to 4.2.3 Singular, plural, & collective nouns

- In the COCA, select NOUN.all from the POS menu by the side of the search bar. Once selected, the tag NOUN will appear in the search menu. Also, select Blog from the register options. In the output, determine which of the top 20 most frequent nouns are count and which are non-count.

- The following samples are present in the TV/Movies subsection of the COCA.

- “We got two Denver omelets, one over-easy; three orange juice, and two coffee. Would you like cream?”

- “Can I get two cheeseburgers, no tomatoes, and two french fries? Better make that two coffees.”

It is likely you evaluated the second as more common and/or acceptable. Explain why you feel the first feels somehow odd or strange? Do you think it may occur one day where the pattern present in the first is preferred over the second? What other noncount nouns do you sometimes add the plural -s-? Search for one of these additional typical noncount nouns but with a plural -s- in the corpus. Are there many instances of its use?

⇒ Return to 4.2.4 Count & non-count nouns

⇒ Return to 4. Nouns

Module authors: Robert Poole

Last updated: 16 November 2022

This module is part of Critical Language Awareness: Language Power Techniques and English Grammar, an open educational resource offered by the Clarify Initiative, a privately funded project with the goal of raising critical language awareness and media literacy among students of language and throughout society.