5. Address Forms & Pronoun Choice

Jonathon Reinhardt and Anuj Gupta

⇒ 5.1 Introduction: Why are pronouns such a big deal these days?

⇒ 5.2 Pronouns and address forms

⇒ 5.3 How has the use of pronouns changed over time, and why?

⇒ 5.4 Generic & specific ‘you’

⇒ 5.5 Inclusive vs. exclusive ‘we’

⇒ 5.7 Gender-neutral third person pronouns

Watch the video introducing this module ⇒ The Power of Pronouns

5.1 Introduction: Why are pronouns such a big deal these days?

Module preview questions

What is your experience with third person-pronoun choice? Why do you think some people support it while others take issue with it? What rights do you think an individual has with regards to how others name or address them?

In 2016, a big controversy erupted at the University of Michigan. In order to foster an environment of inclusiveness, administrators at the university gave all the students the right to choose a personal pronoun of their choice and have it reflected in the class roster. All University members would need to address students using their chosen pronouns (Fitzgerald, 2016).

While many students and faculty rejoiced at the progressive step this policy would take which was in sync with their principles of gender social justice, several others felt that this was both absurd as well as a form of repression on their freedom of speech. The controversy started when one student, Grant Strobl, listed his pronouns as “His Majesty” on the university portal and asked all teachers and students to refer to him with it in order to call out what he believed to be the absurdity of this policy.

Since then, numerous such conflicts have emerged on campuses across North America with both pro and against sides making charged arguments in favor of or against people designating their own pronouns.

If you have time and interest, watch this video to learn Strobl’s position. “University allows students to choose their own pronouns. Fox News Report, 1 Oct 2016”:

5.2 Pronouns and address forms

A pronoun is a specific type of word that represents and replaces a noun or noun phrase, and there are a limited number of them. If we didn’t have pronouns, we’d have to repeat names and nouns every time we spoke and wrote. Instead of having to say something like:

Vaccines? That woman is a doctor so that man should ask that woman about vaccines

we can say

Vaccines? She is a doctor and so he can ask her about them.

There are different types of pronouns: personal pronouns like ‘you’ and ‘us’, demonstrative pronouns like ‘this’ and ‘that’, and reflexive pronouns like ‘myself’ and ‘themselves’. Pronouns can be marked for number (singular or plural), person (first, second, third), case (subject or object), and gender (male, female, neuter, neutral), but not all pronouns are marked for the same features.

First person (1P) personal pronouns like ‘I, me, mine, we, us, ours’ refer to the speaker(s) or writer(s), while the second person (2P) pronouns ‘you, yours’ refer to the addressee – that is, who the speaker or writer is addressing. Third person (3P) pronouns, ‘it, its, she, her, hers, he, him, his, they, them, theirs’, are used to refer to a thing, concept, or person that has been previously mentioned but that is not being addressed directly. Personal pronouns include the possessive pronouns ‘mine, yours, his, hers, its, ours, theirs‘, but technically the words ‘my, your, his, her, its, our, their‘ are determiners, not pronouns, because they modify/precede a noun and cannot stand alone.

Address forms are names or titles we use when we address or refer to other people – they are similar to nicknames, but they can be used universally and are socially recognized. In English we traditionally use address forms like ‘mister, sir, madam, ma’am, miss’ as honorifics or respect forms to show respect towards, or the independence of, the addressee or referent – honorifics can usually be used by themselves, e.g. ‘Sir’, or they can precede a name, e.g. ‘Mister Jones’. Address forms can also be neutral, as in the use of given (first) names in the US, and they can also show disrespect, as in name-calling, slurs, and abusive profanity. They can also be intimate, like ‘bro’, ‘honey’, or ‘dear’. Intimate forms are used to show solidarity and make an appeal towards friendship, involvement or rapport. By the way, if you are US American, you should know that it sounds odd in many cultures to use ‘pumpkin’ as an intimate form of address. Maybe pumpkins are considered endearing in the US because of Hallowe’en.

Because pronouns are used to refer to other people, when we use them we imply a relationship between us (the speaker or writer) and whomever is being addressed or referred to. Historically, English had two 2P forms: ‘thou’ and ‘you’. ‘Thou’ was used as the familiar pronoun for one person, while ‘you’ was the formal pronoun for one or more people, but between the 1600s and 1800s, people stopped using ‘thou’, and ‘you’ took over. Interestingly, in standard English we still say ‘you are’ and not ‘you is’, even though we use it to refer to a single person. In Spanish the familiar form of ‘you’ is ‘tu’ and the respect form is ‘Usted’; many other languages have two 2P pronouns that are distinguished according to their social use.

Like address forms, pronouns not only imply relationships, but also identities. If I use ‘he’ to refer to someone, it means I ascribe their identity as male. In other languages, even the use of 1P and 2P pronouns can imply the speaker or listener’s gender identity, for example, in Japanese, there are different pronouns for ‘I’, one traditionally used to assert a male identity (‘boku’) and another used to assert a female identity (‘atashi’).

If you have the time and interest, take a look at these webpages to learn about:

- the many different terms of endearment used in English and other languages:

- Japanese personal pronouns:

Key points from 5.2

- Pronouns are a key part of English grammar that allow us not to have to repeat nouns over and over.

- A speaker’s (or writer’s) choice of address form can show respect, rapport, disrespect, or intimacy between the speaker and addressee.

- As address forms, the pronouns we choose to use reflect our understandings of social relationships and our own identities

Activity 5.2 Pronouns & address forms

a. Identify the pronouns

b. Read this brief webpage by Thoughtco.com on terms of address and discuss or reflect on the following: https://www.thoughtco.com/term-of-address-1692533

- How do you address medical doctors, teachers, aunts, uncles, and grandparents? What is considered respectful or disrespectful? How does this compare to others’ terms, and how does it compare to other languages that you know? Why do you think that these uses can be different?

- Consider the words ‘man’, ‘sir’, ‘ma’am’, ‘lady’, ‘girl’, ‘boy’, ‘brother’, and ‘sister’ as address forms. When are they used, and for what purpose? Which uses do you consider polite, rude, or offensive?

c.

5.3 How has the use of pronouns changed over time, and why?

The use of address forms has changed over time; most agree that accepted usage has become less socially rigid over time, and more formal forms are being dropped by younger generations. While address forms shift generation by generation, it is more difficult to change the use of pronouns over time, however, because pronouns are a closed class. We can’t easily add new words to closed classes since they serve grammatical purposes, standing in for full noun phrases and providing discourse coherence by connecting referents. Still, the meanings and uses of existing pronouns in English have shifted over time, sometimes through conscious effort.

For example, in the 1650’s during the English Civil War the Quakers were considered radical because they wanted to create an egalitarian society that challenged the hierarchies and formalities established by English royalty and aristocracy. At that time, English society was rigidly divided into classes and elaborate systems of address forms maintained these hierarchical divisions. While we now use “you” as a common 2P pronoun for everyone, irrespective of the person’s social status, in those times “you” was reserved exclusively to address people of high social status, while “thou” and “thee” were used to address an equal or someone with lower social status (“ye” was plural). If a poor man spoke to a wealthy man, he was supposed to use the formal 2P pronoun “you” to address him, while the rich man would use the familiar 2P pronoun “thou” to address the poor man.

The Quakers wanted to change this system because it violated their beliefs (Bejan, 2019). George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, said that God “forbade me to put off my hat to any, high or low; and I was required to thee and thou all men and women, without any respect to rich or poor, great or small” (Bejan, 2019). According to their beliefs, no human was between an individual and God – not the Pope and not the King of England. As captured in the King James Bible, it was considered normal to refer to God with the familiar ‘thou’ rather than the respectul ‘you’, because ‘you’ implied that God was distant, not familiar, as the Quakers believed. Thus, as a form of political protest and religious expression, the Quakers used ‘thou’ even to the aristocracy! Facing a lot of ridicule and persecution for using language in different ways, some sought refuge in the American Colonies, especially Pennsylvania, which was founded by Quaker William Penn.

Another example of how pronoun use changes over time is the gradual loss of the ‘royal we’ or ‘majestic pronouns’. If you’ve seen movies about the English royalty, you might be familiar with how people of royal descent refer to themselves using plural pronouns like “we”. For example, in 1902, Edward VII of England proclaimed in a treaty: “Now, We, Edward, by the grace of God, […] have arrived at the following decisions upon the questions in dispute” (source: Wikipedia). The ‘royal we’ is no longer used in everyday situations, except perhaps by celebrities and aspiring socialites who want to be considered majestic.

Key points from 5.3

- Address forms and pronoun uses have shifted throughout the history of English, sometimes because of shifts in how younger generations use language differently than older generations, and sometimes intentionally as the result of social protest.

- Unlike many other languages, English no longer has a 2P pronoun system that can indicate unequal social relationships; respect and rapport are shown in other ways.

Activity 5.3: Changing pronouns and address forms

a. Shakespeare wrote in a variety of English called ‘Early Modern English’, spoken from about 1100 to 1600 CE. We can still understand Shakespearean English because, even though language changes over time, English hasn’t changed enough since then so that Shakespeare is unintelligible, it just requires effort. His was the first recorded use of many modern English words, but many other words he used are no longer commonly understood. He also used structures that are no longer used, and he used both ‘thou’ and ‘you’ – ‘thou’ when he wanted a character to express familiarity to the addressee, and ‘you’ when he wanted an expression of formality. In reality, however, uses were mixed, sometimes by a pair of people when talking, for various reasons. Read about how these pronouns on this webpage by nosweatshakespeare, then discuss/reflect on the question that follows.

In modern English we no longer use ‘thou’. How do we use language instead to express social distance, respect, solidarity, and rapport? What language besides address forms and pronouns do we use to imply social relationship status?

b. The titles “Sir” and “Ma’am” have their origins in British aristocracy. Initially used to refer only to knights and royalty, during the colonial era, oppressed subjects of colonies like India were forced to use these terms to broadly refer to anyone from the British community. The purpose of this strategy was to create a hierarchical distance between the colonized and the colonizers so that the two could never be seen as equals. These terms carry on even today in India where people on a lower rung of a social or economic ladder are expected to address people above them using such terms. Many organizations are working to challenge these norms; for example, the Congress party, an Indian political party, recently created a new policy asking all its party members in the Indian state of Kerala to drop the use of “Sir” and “Ma’am” in official communication and instead to use terms like ‘chetta’ (a Malayalam word which means elder brother) and ‘chechi’ (a Malayalam word which means elder sister) in order to evoke a sense of familiar relationships between people who belong to different levels of their organizational chart. Read more about this attempt to sanction new forms of address and discourage others in this report by theprint.in, then discuss/reflect on the question that follows.

Do you think an organized movement can successfully change which terms of address are used? If so, what do you think it takes? Do you think the Congress Party’s movement in Kerala will be successful? Why or why not?

5.4 Generic & specific ‘you’

The merging of familiar ‘thou’ and formal ‘you’ into just ‘you’ has given the pronoun broad powers. It can be used to address a person respectfully, e.g. “Mr. President, did you sign the bill?”, it can be used to address a person intimately, e.g. “I love you”, and it can be used to address more than one person together (although some varieties of English use ‘y’all’, ‘you guys’, or ‘youse’ for plural you). Many other languages have two or more different forms for those three purposes, for example Spanish has ‘tu’, ‘Usted’, and ‘Ustedes’. Another powerful use of ‘you’ in English is called the ‘generic you’, the use of ‘you’ to address anyone listening or reading without being specific, meaning ‘one’, ‘everyone’, or ‘anyone’. Contrasting with the specific you, its interpretation is context dependent. For example, in:

- You should bring a raincoat if you visit Seattle in the spring.

- When you turn 40 you should get life insurance.

the advice can apply to anyone, and so the ‘you’ is generic. But in:

- When you turn 40 you should get life insurance, Bob.

- You should bring a raincoat when you visit Seattle this summer.

the ‘you’ is referring to a specific person. To tell if a use of ‘you’ is generic, replace the ‘you’ with ‘one’, and if it makes sense, it is a generic use. So,

- One should bring a raincoat if one visits Seattle in the spring.

- When one turns 40 one should get life insurance.

make sense, so the you is generic. However, with:

- You are an excellent singer.

- Did you finish your homework?

it sounds a bit odd to say:

- One is an excellent singer.

- Did one finish one’s homework?

so ‘you’ in these examples is specific, not generic.

Generic you is powerful because it can be heard as general advice or a proclamation of truth that applies to anyone, so a listener feels as if they are being addressed, as part of an in-group. For this reason it can be found in advertising, for example:

- Red Bull gives you wings.

- Visa. Everywhere you want to be.

- M & Ms melt in your mouth, not in your hands.

Dr. Ariana Orvell and colleagues, psychologists at the University of Michigan (2020), analyzed Kindle data from 1,900 users reading 56 different books and found that readers highlighted passages containing generic you more often than would be statistically probable, as if the readers felt they were being addressed. They argue that this is evidence that generic you can resonate with readers and listeners and help them feel a personal connection with the author and the content, even when they know rationally that they aren’t being addressed specifically.

Finally, imperatives (commands) in English that addressed to a single person or a group do not use the word ‘you’, but they imply it. Commands can therefore be either obviously generic or specific, or ambiguous, which gives them a unique kind of persuasive power.

- Finish your homework and you can play video games. (clearly specific)

- Brush your teeth every night before bed. (clearly generic)

- Just do it. (ambiguous)

- Think different. (ambiguous)

- Make America Great Again (ambiguous)

Key points from 5.4

- The pronoun ‘you’ has unique power because it can be used both specifically and generically. An ambiguous use can be interpreted either way.

- The careful use of a ‘generic you’ can cause ‘resonance’ in a listener or reader, especially in a context focused on general advice and proclamations.

- The deliberate use of a ‘specific you’, especially in a context like advertisement or recruitment, can make a listener or reader feel directly spoken to and that they need to respond somehow.

- ‘You’ is the subject, but is not stated, in commands. They can also be generic, specific, or ambiguous.

Activity 5.4 You oughta know when you’re being addressed

a. Canadian songwriter Alanis Morissette is well-known for her hit 1995 album, “Jagged Little Pill”. Search for the album online and listen to the lyrics of the songs on the album that include the pronoun ‘you’ in their titles.

Which “Jagged Little Pill” song or songs use the generic you, and which use the specific you? What is the effect of these uses on listeners? How do you think the songs ‘resonate’ differently?

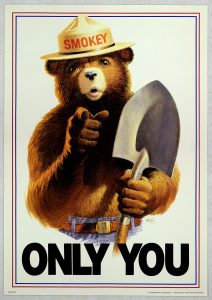

b. The well-known Uncle Sam WWII army recruitment and 1940s Smokey Bear posters were designed with the clear goal of influencing behavior. They clearly used the specific you.

What feelings or emotions do you think a viewer would have seeing these? In what context do you think they were most effective?

c. Looking at advertisements or political discourse, find three examples of the use of ‘you’ and note who is the author or speaker and in what context it is used. Find one use that is clearly generic, one that is clearly specific, and one where it is ambiguous. Remember that commands count, too.

5.5 Inclusive vs. Exclusive We

‘You’ is not the only pronoun that can be used strategically because it has ambiguous referents. The 1P plural pronoun ‘we’ and its variations ‘us’ and ‘ours’ in English can also be used strategically because ‘we’ can have an inclusive meaning of ‘I the speaker/writer and you the listener/reader’, or it can have an exclusive meaning of ‘I the speaker and someone else but not you the listener’. Using the inclusive we is an appeal towards involvement, for example, if you’re talking to someone and you refer to something you did together. However, if someone uses ‘we’ to refer to something they did with others and you were not part of that group, it is clear it is a use of the exclusive we (although its use does not necessarily mean the listener was purposefully excluded). Exclusive we is used often in ‘us vs. them‘ rhetoric (see 5.6 below). The phrase ‘let us’, contracted as ‘let’s’ is used as the 1P imperative form, and it automatically sounds inclusive. However, someone can use it to give directives and make suggestions to others even if they do not mean to follow the directive themselves; for example, when a professor says ‘Let’s take the test now’, they know very well they aren’t taking the test. But it makes them sound like they are involved.

Because of this ambiguity, the use of ‘we’ or ‘us’ is potentially quite powerful. Because humans naturally want to belong to a group, English users may interpret ‘we’ as inclusive, unless they know explicitly that they are not part of the group being referred to. If you are listening to a politician giving a speech to a group you actively do not identify with or are not a part of, when the politician uses ‘we’ you may judge it as exclusive and not meant to include you. However, when any politician uses ‘we’ to refer to a vaguely defined group that might include you, it is difficult to hear ‘we’ as exclusive of you.

Inclusive ‘we’ is used by leaders on all parts of the ideological spectrum to appeal to a sense of community, solidarity, and belonging. The Finnish linguist Tyrkkö (2016) found that the use of inclusive we pronouns in political speeches around the world has increased in the past 100 years; this could be due to the rise of democracy and the use of propaganda techniques like plain folks appeals, where politicians attempt to appear from an average, middle or working class background, even though they may come from an upper class background.

If you have time and interest, learn more about plain folks appeals at the websites Propaganda Critic and Logically Fallacious.

A leader can unite and inspire followers by strategically using the inclusive we, and since 1900, US American politicians have increasingly used forms of inclusive we more frequently than 1P ‘I’ pronouns (Tyrkkö, 2016). For example, watch the will.i.am video “Yes We Can”, based on a campaign speech Obama gave in 2008.

‘We’ is sung 80 times in will.i.am’s song lyrics, and Obama used ‘we’ 45 times in his speech. If you have time and interest, read the full transcript of the speech:

Key points from 5.5

- The pronoun ‘we’ (along with us and ours) can be used strategically because it has both an inclusive and exclusive meaning.

- Because it is perceived to imply inclusivity, the use of ‘inclusive we’ can appeal to solidarity and a sense of unity. It can make a plain folks appeal.

- However, the use of ‘exclusive we’ implies division when used in ‘us vs. them’ language.

Activity 5.5: Who is accountable?

a. Besides politicians, who else might use ‘we’ strategically to imply inclusivity, or emphasize exclusivity? Find an example from the real world.

b. Dahnilsyah (2017) analyzed Obama’s presidential speeches and argued that he used pronouns in a manner that was “rhetorical, persuasive and manipulative”. What lies below is an extract from a speech that Obama gave after a terrorist attack attempt on a Northwest Airlines flight. Read the excerpt and notice the pronouns. How does Obama use ‘we’ and ‘our’ strategically? Which are inclusive and which are exclusive? How does this allow him to take, or avoid, individual responsibility? What other effect does it have?

“I believe it’s important that the American people understand the new steps that we’re taking to prevent attacks and keep our country safe. In our ever-changing world, America’s first line of defense is timely, accurate intelligence that is shared, integrated, analyzed and acted upon quickly and effectively. That’s what the intelligence reforms after the 9/11 attacks largely achieved. That’s what our intelligence community does every day” (Obama qtd. in Dahnilsyah, 2017, p.65).”

5.6 Us vs. Them

Taking advantage of the in-/ex-clusive ambiguity of ‘we’, politicians and others can strategically juxtapose them with uses of the third-person plural ‘they’ pronouns in an ‘us versus them‘ technique, drawing sharp black-and-white contrasts between the two groups so that they are perceived as 100% oppositional. Because the people ‘they’ represent are not present during such discourse, they cannot argue otherwise. Offering only two polarized choices and forcing people to choose between the two – implying that “you are either with us or against us” – presents a false dichotomy, a propaganda technique that has been used for ages. Because it is simpler to quickly choose between black and white rather than to consider shades of gray or other colors, this ‘us vs. them’ strategy works to unite people by not only what they think they are (us), but what they do not want to be (them).

If you have time and interest, learn more about false dilemma and false dichotomies on the wikipedia entry and at the website Propwatch:

Political scientists Matos and Miller argue in their research (2021) that Donald Trump strategically used pronouns in this way to promote bonding among his core followers during his campaigns, more so than his opponents did. Using the ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ dichotomy, Trump encouraged “outgroup hostility” or hostility against those his followers believed to be “outsiders” in their minds. According to Matos and Miller’s study, Trump created an identity story whereby he “framed ingroup attitudes among white Americans by answering three main questions: ‘who are they,’ and thus, ‘who are we,’ and ‘what’s at stake (what do we have to lose)’ (pg. 2)”. The answer to these questions involved defining “the ingroup (we, us) as “good” and superior in comparison to framing the outgroup (them) as “bad,” as criminals and terrorists, as foreigners, and importantly, as people who wanted to take what rightfully belonged to the ingroup. Trump used immigration and the refugee crisis to define the outgroup (pg. 2). Continuously using pronouns in this way creates a powerful cognitive frame which may promote “groupthink” and prevent individuals from rationally weighing evidence, considering complexity, and making up their own minds. Such skillful rhetoric may make listeners more amenable to what politicians say, as it implicitly appeals to their need to feel part of a ingroup, especially when that ingroup’s identity also aligns with culturally-conditioned prejudices.

Key points from 5.6

- First person plural pronouns (we/us/ours) are especially powerful when juxtaposed with the use of third person plural pronouns (they/them/theirs) because it sets up a potential false dichotomy between the ingroup and an absent outgroup that cannot defend itself.

Activity 5.6 Who are we?

a. Anybody can use language strategically to motivate their audience and create a sense of shared, ingroup identity. For example, the following text is from an email from the Arizona Democratic Party soliciting a donation, sent to a registered Democrat. Read the excerpt and identify the pronouns, then reflect on/discuss the question.

“Our reproductive rights and privacy are at stake. The AZ GOP has cheerleaded every day since the Dobbs decision came out, and they openly support an 1800’s near-total abortion ban that requires jail time for doctors. Some candidates want a national abortion ban and even a ban on contraceptives. This is a direct attack on our rights and on our privacy. We can’t let the AZ GOP drag us back to the 1800s on health care.” (an email soliciting donations from AZ DEMS, received August 29, 2022)

How does this solicitation use pronouns to create a sense of ‘us vs. them’? What other language choices contribute to a sense of ingroup identity? What language is used to give a sense of urgency and shared goals?

b. Watch this video on the science behind ‘us vs. them’ by Dan Shapiro and Robert Sapolsky of Big Think. Discuss/reflect on the questions below afterwards.

What can be done to counter the destructive potential of ‘us vs. them’ rhetoric and thinking? In what situations, if any, do you think the use of ‘us vs. them’ techniques are ever justified?

5.7 Gender-neutral third person pronouns

While English has ‘it’ to refer to non-humans, according to traditional grammarians, users must choose ‘he’ or ‘she’ when referring to humans. The sentence ‘Everyone must bring their own lunch’ is incorrect according to traditionalists because ‘everyone’ is singular, and so ‘their’ should be a singular ‘his’ or ‘her’ so that the referent agrees with its antecedent. However, this supposedly traditional rule was actually invented in the 1800s, and before that, English users made use of singular they just as they do now.

If you have time and interest, read this entry on the Oxford English Dictionary blog about the history of the singular they:

Other gender-neutral pronouns have been proposed for trans, non-binary, or genderqueer people in English, but since pronouns are a closed class and the matter has been politicized in the USA, widespread adoption and acceptance has been difficult. However, other languages with more centralized control and fewer speakers have successfully done so, for example, the Swedish government and academics have adopted ‘hen’ instead of ‘han’ (he) and ‘hon’ (she) as a gender-neutral 3P pronoun for humans, in an attempt to create gender equality.

If you have time and interest, read this brief NPR story about the Swedish movement to adopt a new gender-neutral pronoun:

Key points from 5.7

- The pronoun ‘they’ has been used for singular referents for centuries in English. This usage has been rejected by strict grammarians who restrict it to plural usage, even though the pronoun ‘you’ has broadened its usage from only plural referents to also include singular referents.

- There have been many attempts over the past few centuries by language reformers to create new gender-neutral singular 3P pronouns for humans.

Activity 5.7 Why doesn’t English have gender-neutral 3P pronouns?

a. Throughout history there have been attempts to invent new gender neutral 3P pronouns for humans in English and promote their use. Read this piece on the history of these attempts:

Why do you think past attempts to promote new gender neutral pronouns for English have failed to be successful? Why do you think it might be especially difficult to get people to use new third-person pronouns?

b. Most recently the debate on 3P pronoun use has become highly politicized, with conservatives arguing that forcing people to use new pronouns to refer to others when those others are not present is a restriction of their right to free speech, while liberals argue that we should respect the rights of individuals to be referred to as they wish. Watch this debate on Canadian Broadcasting between Jordan Peterson and A.W. Peet on the controversy:

Which arguments do you find most or least convincing for using, or not using, new gender-neutral pronouns? What practices do you follow, and why?

c.

Reflection/Discussion Questions

Reflect on the content of this module by answering some or all of the following questions. Provide examples to support your points.

- What are address forms and how do they reflect social relationships and identities?

- What can we learn from the past about the potential future of pronouns in English?

- How can the pronouns ‘you’,‘we’, and ‘they’ be used strategically? In what contexts does this happen?

- How can you be aware of when pronouns are being used strategically to sway you?

- What arguments are there for and against using gender-neutral third person pronouns for humans? Which are stronger and weaker arguments, and why?

⇒ If you are doing the corpus activities, try the module corpus activity next: Pronouns and inclusive language use: The case of ‘you guys’ and ‘y’all’

5.2 Pronouns and address forms

- Pronouns are a key part of English grammar that allow us not to have to repeat nouns over and over.

- A speaker’s (or writer’s) choice of address form can show respect, rapport, disrespect, or intimacy between the speaker and addressee.

- As address forms, the pronouns we choose to use reflect our understandings of social relationships and our own identities

5.3 How has the use of pronouns changed over time, and why?

- Address forms and pronoun uses have shifted throughout the history of English, sometimes because of shifts in how younger generations use language differently than older generations, and sometimes intentionally as the result of social protest.

- Unlike many other languages, English no longer has a 2P pronoun system that can indicate unequal social relationships; respect and rapport are shown in other ways.

5.4 Generic ‘you’

- The pronoun ‘you’ has unique power because it can be used both specifically and generically. An ambiguous use can be interpreted either way.

- The careful use of a ‘generic you’ can cause ‘resonance’ in a listener or reader, especially in a context focused on general advice and proclamations.

- The deliberate use of a ‘specific you’, especially in a context like advertisement or recruitment, can make a listener or reader feel directly spoken to and that they need to respond somehow.

- ‘You’ is the subject, but is not stated, in commands. They can also be generic, specific, or ambiguous.

5.5 Inclusive vs. Exclusive We

- The pronoun ‘we’ (along with us and ours) can be used strategically because it has both an inclusive and exclusive meaning.

- Because it is perceived to imply inclusivity, the use of ‘inclusive we’ can appeal to solidarity and a sense of unity. It can make a plain folks appeal.

- However, the use of ‘exclusive we’ implies division when used in ‘us vs. them’ language.

5.6 Us vs. Them

- First person plural pronouns (we/us/ours) are especially powerful when juxtaposed with the use of 3P plural pronouns (they/them/theirs) because it sets up a potential false dichotomy between the ingroup and an absent outgroup that cannot defend itself.

5.7 Gender-neutral third person pronouns

- The pronoun ‘they’ has been used for singular referents for centuries in English. This usage has been rejected by strict grammarians who restrict it to plural usage, even though the pronoun ‘you’ has broadened its usage from only plural referents to also include singular referents.

- There have been many attempts over the past few centuries by language reformers to create new gender-neutral singular third-person pronouns for humans.

- address forms

- addressee

- case

- demonstrative pronouns

- exclusive we

- false dichotomy

- familiar pronoun

- first person

- formal pronoun

- gender

- gender-neutral pronouns

- generic you

- honorific

- imperative

- inclusive we

- intimate forms

- number

- person

- personal pronouns

- plain folks

- possessive pronouns

- pronoun

- reflexive pronouns

- respect forms

- second person

- specific you

- third person

- us versus them

Know this vocabulary? Test your knowledge in this crossword puzzle.

Module authors: Jonathon Reinhardt and Anuj Gupta

Last updated: 7 October 2022

This module is part of Critical Language Awareness: Language Power Techniques and English Grammar, an open educational resource offered by the Clarify Initiative, a privately funded project with the goal of raising critical language awareness and media literacy among students of language and throughout society.

a word like 'we', 'hers', or 'someone' that represents and replaces a noun or noun phrase

a pronoun like 'I, them, yours' that is often marked for person (first, second, third), number (singular or plural), case (subject, object, possessive), and gender (masculine, feminine, neuter, neutral)

are pronouns that point towards specific things and are marked for number (singular or plural) and proximity to the speaker (near or far). They include this, that, these, & those, and can also be demonstrative determiners.

pronouns that include the -self or -selves suffix. They are marked for number (singular or plural), and can only be used as appositives and objects, not subjects.

in grammar refers to the quality of being singular or plural (i.e. more than one)

in grammar refers to perspective of the speaker or writer: first person (e.g. I, we), second person (e.g. you), and third person (e.g. it, they)

in grammar is a category of syntactic function, i.e. what role the word or phrase plays in the sentence. In general, subject case is for what does the action, and object case is for what receives the action.

in English grammar refers to the sex of the human referent -- male (he, him, his), female (she, her, hers), or neutral (they, them, theirs).

First person (or '1P') means from the perspective of 'I'. 1P pronouns are I, me, mine, myself, we, us, ours, & ourselves.

Second person (or '2P') means from the perspective of 'you'. 2P pronouns are you, yours, yourself, & yourselves.

who the speaker or writer is addressing or speaking to, part of the audience (which may include non-addressees)

Third person (or '3P') means from the perspective of 'he, she, it', or 'they'. 3P pronouns are he, him, his, himself, she, her, hers, herself, it, its, itself, they, them, themself, & themselves. 'Who', 'whom', and indefinite pronouns are also 3P.

names or titles we use when we address other people, like 'mister', 'buddy', 'ma'am', or 'honey'. They can be respectful, neutral, or intimate.

are words preceding a name, like a title, that show respect to the holder, e.g. 'Mister', 'Doctor', 'Miss', 'Professor'. Some are, and some are not, used without the name.

address forms like honorifics and formal pronouns that show respect from (or distance between) the speaker to the addressee

address forms that show informality and intimacy between the speaker and the addressee, e.g. 'dear', 'honey', 'baby', 'bro', 'girl', etc.

a form of pronoun (usually 2P) that is used for informal interaction, implying equality. Until the 1800s in English, 'thou' was the familiar 2P pronoun form in contrast to the formal form 'you'. Other languages like Spanish, French, and German still have distinct familiar and formal 'you' pronouns.

a form of pronoun (usually 2P) that is used for formal interaction, implying respect and distance. Until the 1800s in English, 'you' was the formal 2P pronoun form in contrast to the informal form 'thou'. Other languages like Spanish, French, and German still have distinct familiar and formal 'you' pronouns.

the use of 'you' to mean 'one' or 'anyone'-- addressing not a specific individual but anyone

the use of 'you' to mean a specific addressee that the speaker/writer knows or implies they know

the use of 'we' and equivalent first person plural pronouns to refer to the speaker and others that may include the addressee (i.e., when 'we' means 'you and I')

the use of 'we' and equivalent first person plural pronouns to refer to the speaker and others, NOT including the addressee, i.e. 'I and others, but not you'

a language power technique that relies on false dichotomy fallacy to build in-group solidarity and identity through contrast with outsiders

the grammatical voice used to give commands in English. 2P uses just the plain verb (e.g. 'go!'), and 1P uses 'let's' (e.g. 'let's go!').

a power or propaganda technique used to convince audiences that the speaker/subject is common or average, e.g., if a politician advertises themselves eating street food at a fair or taking public transportation

a fallacious way of presenting choices that implies there are two, and only two, opposing options; also called false dilemma or either/or

the use of the pronouns they, them, and theirs to refer to a single individual, which allows not having to refer to the individual's gender identity

pronouns that can refer to humans without specifying their gender, e.g. English 'they' and proposed pronouns like 'hir', 'xe', and 'co'

a title or address form like 'Dr.', 'Mrs.', or 'sir' that shows respect to the addressee or referent

a pronoun that means 'something belonging to' in the possessive case, marked for person (first, second, third), number (singular or plural), and gender (masculine, feminine, neuter, neutral). In English they are 'mine, yours, his, hers, its, ours, theirs'; note that 'my, your, his, her, its, our, their' are technically possessive determiners, not pronouns, because they modify a noun.