1 Essential Concepts

Key takeaways for this chapter…

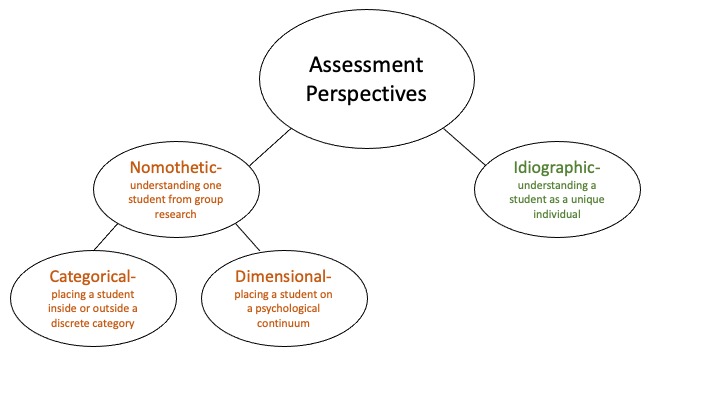

- The concepts of nomothetic and idiographic are useful in school practice

- There are many types of school-based social-emotional evaluations, not just one

- It is helpful to know about DSM-5, but in practice simpler classifications schemes are often used

- For school practice, distinguishing administrative and clinical labels is often important

- It is useful to distinguish between dimensional and categorical conceptualizations in school practice

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- The practice challenge confronting Amy Garcia and Jack Bolden

- Elementary student Rusty, clinical or administrative label?

- Angela, a prospective candidate for social skills treatment

- Jing Wang, looking at students dimensionally and categorically

- Chelsea Washington, a third-grade teacher

When most of us first open a novel we hope to get right to the storyline. Things are equally true when books, like this one, are designed to teach something practical. Rest assured that this chapter and the ones that follow will indeed teach you how to conduct school-based social-emotional assessments. But doing so is not uncomplicated. It’s necessarily unlike learning to handle the controls of a hobbyist’s drone, bake a soufflé that doesn’t collapse, or administer a 60-second reading probe. Effective social-emotional assessments depend on grasping a number of foundational concepts coupled with learning some tool-specific facts. Further complicating matters, sometimes graduate students (as well as practicing professionals) harbor misconceptions about school-based assessments. It’s also true that we humans are universally subject to errors of thinking that make us prone to flawed decision making, including mistakes that are apt to occur while conducting assessments. This means that there is material to be covered before the practical, how-to, part of this book can start in earnest. In this chapter you get a foundation that will help you later. Some of this content may at first seem abstract and unfamiliar. Rest assured, however, that as you work through the book’s chapters that novel ideas will soon become familiar. Also note that when you finish reading this chapter, accompanying Skills Workbook exercises can make things more concrete. Let’s first take a look at a practical situation.

Two school psychologists have conducted evaluations that can help us start to understand the assessment process. Both assessments included student interviews. The first school psychologist, Amy Garcia, skillfully builds rapport with her reticent tenth-grade student. General inquiries about daily routines and likes and dislikes eventually give way to more specific questions. These include topics of worry, nervousness, muscle tension, restlessness and sleep problems. Amy works systematically. She is sure to check each of several psychological and physical dimensions as she pleasantly engages this young lady. Amy is addressing textbook-like criteria to help her confirm or disconfirm an important consideration—might this student have a diagnosable anxiety condition?

The second school psychologist, Jack Bolden, is equally attentive to initial rapport building. He, too, engages his student, a second grader, conversationally. But Jack’s interview is largely devoid of anxiety-related questions that characterized Amy’s inquiries. In fact, his interview has little to do with the presence or absence of delineated psychological symptoms. Instead, Jack’s probes center on the student’s perceptions of his school environment, his view of classmates, his comfort in the classroom and on the playground, his feelings of achievement, plus his sense of emotional investment in the school community. Jack also asks about fear, but he does not seek to determine whether or not this boy suffers an anxiety disorder. Rather, Jack’s purpose is to understand the unique perceptions, attitudes and school-related emotional dispositions of this student. In doing so, Jack aims to discover why this student’s school behavior has recently worsened.

Nomothetic and Idiographic–Complementary Perspectives

The two terms–nomothetic and idiographic–originally concerned research. But the terms have also long proved relevant to applied practice. Interestingly, Florell (2019) recently authored a chapter entitled “Idiographic verses nomothetic history: The first debate in school psychology.” In it, he recounts that history for novice school psychology students (but the concepts are deeply relevant to us all). Nomothetic research strategies study groups of people and interindividual variation. In contrast, idiographic research strategies focus on just one individual (Haynes & O’Brien, 2000). An idiographic approach concerns intraindividual variation. The essence of these group/individual distinctions carries through when the terms are used in applied practice. Amy Garcia’s interview approach is largely nomothetic. A nomothetic assessment approach seeks information about a specific child that links her to what is already known about large numbers of other children (Beltz, Wright, Sprague & Molenaar, 2016). “Nomos” is the Greek word referring to “law.” In psychology this refers to general laws about human behavior, development, and mental health problems. Importantly, the nomothetic approach helps to bridge a gap between applied practice and large-scale scientific studies.

As you may surmise, Amy speculates that her student may have clinical anxiety. Accordingly, she works systematically through an interview that includes research-derived questions about anxiety. These questions can be universally applied by mental health professionals because childhood anxiety is a widespread phenomenon with shared features. Such features might consequently be used to determine the presence or absence of an anxiety disorder in a single child, a process enabled by statistics (McLeod, Jensen-Doss & Ollendick, 2013). Research shows, for example, that during an interview most youth confirm some symptoms of anxiety but only a very few confirm many such symptoms (Sheehan et al., 2010). Previously collected group data helps practitioners draw a line between these two groups. Even more important, if anxiety is confirmed in a particular student, then an entire suite of empirical information about teens with anxiety becomes available to Amy. That is, Amy (working largely nomothetically) would know a lot about her individual student with anxiety because so much is known about students with anxiety in general.

In contrast, Jack Bolden’s interview approach is largely idiographic. An idiographic assessment approach seeks information about an individual without the context of group data. During interviews, for example, an idiographic approach might center on personal and unique perceptions, feelings, and motives. “Idios” is the Greek word referring to “own” or “private.” Jack may, thus, seek aspects of mental life that are by their very nature known only to the student himself. In this case, Jack seeks to understand this student’s internal state well enough to shed light on his changed school status. Thus, Jack does not ask a fixed set of questions about a potential mental health diagnosis. Alternatively, Jack trusts individually-tailored questions that might reveal conflicts with classmates, lack of trust in a teacher, fear about a specific aspect of the school experience or any of a hundred other possibilities that are impossible to specify beforehand. For Jack and this particular student, it’s about individuality and his one-of-a-kind school experience.

Of course, most social-emotional assessments are not confined to student interviews. To help better understand these two complementary concepts, let’s assume interviews were not used in either case. In our example, however, both Amy and Jack retained their respective nomothetic and idiographic approaches. What might that look like? Amy, who is operating from a nomothetic perspective, might rely on standardized social-emotional rating scales. For example, she may use the immensely popular Behavior Assessment System for Children-Third Edition (BASC-3; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015). The BASC-3 permits the student to rate herself regarding anxiety, as well as many other psychological dimensions, and for her parent(s) and teacher(s) to do the same. Alternatively, Amy might select a self-rating scale that addresses anxiety solely, such as the Revised Manifest Anxiety Scale, Second Edition (RCMAS-2; Reynolds & Richmond, 2008). You will learn much more about using the BASC-3, as well as other broadband rating scales, in Chapter 5. Chapter 7 will help you learn when and how to use narrow band scales, like the RCMAS-2.

Jack, true to the idiopathic notion, might skip rating scales in favor a behavioral assessment. In doing so, he observes the student several times during class as well as in other campus settings. His focus is on unique patterns among antecedents, behaviors and consequences that might help explain this student’s actions. Unlike, group-comparison, nomothetically-oriented Amy, Jack need not concern himself with whether this student’s behavior is unlike that of his classmates. His idiographic approach is all about patterns for this student uniquely. Jack addresses intra-individual variables, Amy inter-individual variables.

This discussion seems to beg the question, which orientation is better? Well, let’s look at the pluses and minuses of each perspective. Amy’s nomothetic interview and rating scale usage gets the first look. If Amy can confirm the presence of an anxiety disorder, she has accomplished something practically important. Group-level research shows that anxiety disorders are extremely common among school-age children (Fox & Pine, 2012) and that children with an anxiety disorder demonstrate considerably more impairments in school functioning than counterparts free of an anxiety disorder (Mychailyszyn, Mendez & Kendall, 2010). What’s more, research indicates that anxiety may be associated with school problems because it interferes with working memory and executive functions that are required to succeed in school (Owens, Sevenson, Hadwin & Norgate, 2012). Favorably, research indicates that symptoms of anxiety respond to treatment. Effective interventions include both cognitive behavior therapy (Rapee et al., 2017) and therapeutic exposure to anxiety-producing situations (Peris et al., 2017), the former conferring long-term benefits, such as protection from suicidality (Wolk, Kendall & Beidas, 2015). Thus, one can argue that nomothetic considerations enable practitioners to understand much about an individual student. This understanding also enables formulation of a plan to improve his functioning via off-the-shelf interventions (you will see more about this in Chapter 14). Thus, for some school psychologists, establishing the presence of a diagnosable mental health condition is a great place to start. Often, however, it is a poor place to finish.

But, there are also minuses associated with the nomothetic approach. Assessments confined to seeking a mental health diagnosis often prove too narrow. If Amy’s inquiries represent mere attempts to document the presence of clinical anxiety (i.e., nomothetic) she risks missing the substantial external world and vast internal world in which this student’s anxiety manifests (idiographic). She also will know nothing about the particular situations for this one student in which anxiety might interfere with school success or diminish quality of life.

Amy is a skilled school psychologist. As such, she ends up balancing nomothetic and idiographic perspectives. She will probably address her student’s subjective quality of life, her perceptions of relationships, and her sense of internal and external supports. These things vary even when two students share levels of anxiety that are objectively identical. Amy will probably eventually want to learn about her student’s motivation to improve her life and how the student envisions accomplishing any contemplated improvement. She will also speak with the student’s various teachers and observe in the classroom. Adding idiographic aspects to the nomothetic approach helps Amy more fully understand the student. Idiographic analysis also facilitates intervention. Typically, exclusive reliance on a nomothetic perspective is insufficient. In the next chapter you will discover a handy form for organizing your assessment findings; that form requires you to consider both nomothetic and idiographic perspectives in each of your case formulations.

You can probably anticipate that related pluses and minuses come with Jack’s idiographic interview and his subsequent behavioral analysis. His present assessment, like his colleague’s, is likely to prove too narrow for many purposes. Jack is certainly on solid ground when he investigates situational factors that might explain this boy’s changing school performance. Peer- or teacher-conflict or home life problems (well suited to idiographically-oriented investigations) may explain his problem. Jack incidentally asked about fearfulness; perhaps there is an isolated situation that the student is avoiding. If the student confirmed this particular concern, and a possible motive for avoiding school were established, Jack would be a long way toward understanding and helping the student. In fact, confirmation of idiographic-related possibilities arguably permits understanding of the student in a manner impossible from a solely nomothetic approach. It might also enable a one-of-a-kind intervention plan wrapped around these findings. But, like Amy’s student, Jack’s student might have an anxiety disorder. A purely idiographic approach is blind to this prospect. As such, idiographic approaches fail to tap group-level research findings (i.e., for youth with anxiety in general). This is probably not acceptable in today’s professional world. You will see legal/administrative reasons for this fact in Chapter 10. In this chapter, however, the argument favoring (nomothetically-oriented) diagnosis is practical—to do so bolsters your understanding and your capability to help students.

Mental Health Classification and the DSM-5

As seen in both Amy and Jack’s case, a mental health diagnosis might come into play when a school psychologist selects a nomothetic filter. For illustrative purposes, both Amy and Jack’s cases might have involved an anxiety disorder. But the cases could have just as easily touched upon other well-known disorders, such as ADHD or bipolar disorder.

Warning About Labels

Importantly, however, some scholars, including those in school psychology (Weist, Mellin, Garbacz & Anderson-Butcher, 2019), warn that labels such as those used in mental health should be avoided or dialed back. Labels are sometimes seen as stigmatizing, practically unhelpful, and potentially dehumanizing by focusing on categories rather than individuals. According to the same line of thinking, if labels are necessary at all, then they are best restricted to special education-related classifications. In other words, it might be okay to identify students with conditions like specific learning disability, emotional disturbance or other health impairment but not to go beyond those categorizations. We will consider the role of special education-related terms a couple of paragraphs later. But, as you will see in the chapters that follow, it’s virtually impossible to practice school psychology intelligently without some labelling (or use of a taxonomic system).

One reason for this assertion, of course, concerns the nomothetic approach. Much psychological and educational research would prove impossible without a taxonomy (i.e., without an organized system for labeling and classifying). If there were no terms like ADHD, for example, how might researchers organize empirical investigations about etiology (causes), comorbidity, natural history, social impact, academic impact or treatment? They seemingly couldn’t. In parallel, without a recognized classification system, how might frontline practitioners find and use results from these researchers? They seemingly couldn’t. Consider the words of Oxford University psychologist Dorothy Bishop, “Labels can have negative consequences, but the consequences of avoiding labels can be worse. Without agreed criteria for identifying children in need of additional help, and without agreed labels for talking about them, we cannot improve our understanding of why some children fail or evaluate the efficacy of attempts to help them” (Bishop, 2014, p. 392). What’s more, categorizations (diagnoses) are used extensively outside of schools. Parents often expect that school professionals will also provide them when such disclosures matter. Consider the words of Jeremy Turk, now nearly 20 years old but still apt today, “Nobody wants to learn bad news, but it is a lot better than no news at all. At least you know where you stand” (Turk, 2004, p. 16). More is said on this vital topic in Chapter 13, where the obligation to share oral and written information with parents and students is fully addressed.

The DSM-5 and IDEA, Clinical and Administrative Labels

The notion of labels brings up the topic of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5th Edition (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For context, DSM-5 is a document prepared by psychiatrists for use largely in clinical and research settings. This book’s 947 pages, tucked between two deep purple covers, describes virtually all conceivable mental disorders and the diagnostic criteria for each. All school psychologists should know at least a few simple facts about DSM-5. Among these are that most disorders are diagnosed via confirmation of listed signs and symptoms plus evidence of real-world impairment. DSM-5 mandates that some conditions (e.g., ADHD) evidence impaired functioning in several settings (e.g., symptoms seen just at school but not at home are insufficient to make some diagnoses). Age-of-onset boundaries (i.e., a problem must appear before a specified age or must not first appear after a specified age) are common in DSM-5.

Some school psychologists, especially those practicing in specialized campus settings, probably need detailed knowledge about selected childhood disorders, such as found in DSM-5. A case in point is autism. It’s argued that sometimes autism (the special education term) is too imprecise to accomplish what “autism spectrum disorder” (the DSM-5 term) might. This is said to be true because “the increased detail and structure of the DSM-5 provide guidance to practitioners on areas to prioritize for assessment….leading to selection of services and supports….As experts in psychological diagnosis, school psychologists with detailed knowledge of the DSM-5 can provide advocacy and information to parents and policy makers” (Aiello, Esler & Ruble, 2017, p. 12). Similarly, exact DSM-5 diagnoses are also sought in schools for nomothetic purposes. In other words, for some school psychologists a DSM-5 diagnosis is used to help them understand a student’s nature and then devise disorder-specific interventions. Indeed, more than 25 years ago, Kratochwill and Plunge (1992) advocated just this position (although they also cautioned against leaving out idiographic information). As you will see in later chapters, there are occasions when legal and administrative rules mandate that school districts recognize students with a DSM-5 diagnosis. Thus, DSM-5 use may sometimes prove mandatory, regardless of some school psychologists’ limited enthusiasm for the prospect.

As implied above, some school psychologists dislike DSM-5 diagnoses and oppose their use in schools. Perhaps disdain for DSM-5 springs from a sense that schools already possess their own classification system. In fact, there is a school-based system that comprises special education, not psychiatric, nomenclature. It is codified in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act https://sites.ed.gov/idea/IDEA-History. As you probably already know, the IDEA pull-down menu includes a limited set of special education categories such as specific learning disability, emotional disturbance, intellectual disability, and autism.

The problem is that IDEA and DSM-5 represent two vastly different notions; the first is administrative, the second is clinical (Wodrich, Pfeiffer & Landau, 2008). That is, IDEA categories fail to create groupings of relatively homogenous individuals, which is a prime goal of any science-friendly system of taxonomy. Homogenous groups confer research advantages because they can be empirically studied regarding causes, comorbidities, natural history and effective treatment. Clinical groupings fit hand and glove with the nomothetic perspective. But critically, these science-associated capabilities are lacking for mere administrative labels. For example, Sayal, Washbrook and Propper (2015), working in the United Kingdom, conducted research that untangled the contribution of various symptoms on academic outcomes. Specifically, finely-calibrated academic problems found among 16-year-olds could be predicted by Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) symptoms, ADHD inattentive symptoms, and ADHD hyperactive/impulsive symptoms measured when participants were just 5-year-olds. This research would have been impossible without a system that delineates each of these clinical disorders. In contrast, IDEA administrative labels (e.g., emotional disturbance) are simply too gross to facilitate scientific insights such as these. IDEA labels, nonetheless, work well for the bureaucratic task of documenting how many students receive services in which special education category. In fact, federal and state governmental agencies keep vast statistical databases parsed by special education students’ age, gender, race, and special education category. But this is not scientific research in the traditional sense.

Let’s think a bit more about the limitations of administrative categorization. Consider a third-grade boy named Rusty. He was referred for an evaluation to a team that included a school psychologist. Rusty attends a school with tiered levels of supports. He had already received behavioral interventions created by a school staff member trained in functional behavioral analysis (FBA). His problem, which included careless execution of school assignments, failure to complete other assignments plus disruptive behavior in the classroom, in the cafeteria and on the playground, failed to remit with the use of behavioral techniques. The team’s referral questions included the prospect of eligibility for special education as well as recommendations that might improve Rusty’s behavior and boost his flagging progress in reading and math. The assessment consisted of various techniques. These included standardized behavioral rating scales completed by teacher and parent, face-to-face interview with Rusty’s mother and his teacher, review of records, classroom observation and academic testing.

First, consider what follows if the conclusions about Rusty are confined to educational categorization (i.e., involved just special education categories). The team concluded that Rusty meets criteria for special education and related services in the category of emotional disturbance (ED). But how much does this ED designation inform understanding? The answer is very little. It tells school psychologists next to nothing about why Rusty approaches academic tasks in the manner he does. Likewise, the ED designation sheds no light on his disruptive behavior. It tells the school psychologist and her team nothing about the types of interventions that might work nor whether Rusty is likely to do better, worse or remain similarly troubled as he moves from third to fourth grade.

Second, consider what might happen when more precise clinical labels are used. In this case, Rusty turns out to meet criteria for ADHD plus a type of disruptive behavior entitled Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD). These clinical level designations promote understanding of Rusty’s presenting classroom and academic productivity problems in a way impossible for simple administrative labels like ED. For example, research involving hundreds of youth with ADHD reveals that problems of seatwork carelessness and work incompletion are the rule rather than the exception (Loe & Feldman, 2007). When ODD co-occurs with ADHD, then disruptive behavior across diverse settings is predictable (Harvey, Breaux, Lugo-Candelar, 2016). As seen in the study cited above concerning ADHD and ODD, these classroom problems are unlikely to self-correct as the student ages (Loe & Feldman, 2007). Large scale research studies help confirm what works, and what fails to work when ADHD and ODD are present, such as which parent training programs prove efficacious (Forehand, Parent, Sonuga-Barke, Peisch, Long & Abikoff, 2016). Thus, foregoing clinical labels (and their nomothetic advantages) in favor of just administrative labels risks superficiality and limited utility.

Furthermore, some beginning school psychologists fail to appreciate that DSM-5 diagnoses are ubiquitous. Clinics, hospitals, private practitioners, government agencies, and research articles commonly reference DSM-5 diagnoses by precise name. So do some, but not all, of your school-based colleagues. Consequently, a course devoted to childhood behavior disorders or childhood psychopathology (covering in part DSM-5) represents a valuable foundation for what is learned in this book. A psychopathology course per se, however, is not mandatory. For current practitioners using this book, knowledgeable colleagues can serve to backfill missing information about mental health disorders; for school psychology trainees, course instructors and field-based supervisors can assist. Getting a personal copy of DSM-5, however, is highly recommended for all school psychologists. Plus, there are other resources for school psychologists. Renée Tobin, a school psychology professor, and Alvin House, a clinical psychology professor, have authored a book covering DSM-5 use in schools (Tobin & House, 2015). Their book is helpful because it directs the reader toward specific material relevant for school practice. This is important because DSM-5’s sheer magnitude can prove daunting. Favorably, only a fraction of DSM-5 is actually relevant to school psychologists.

Of course, using diagnostic terms like those found in DSM-5 is controversial aspect of school psychology practice. But a recent position paper by the New Hampshire Association of School Psychologists and the New Hampshire Association of Special Education Administrators (2020) tackles the topic head on. The essential position conveyed in that paper is that school psychologists with proper training (and self-confidence) should feel free to use mental health diagnoses. In part, doing so, as argued in position paper, enables proper determination of special education and Section 504 designation as well as preventing children from having “difficulty accessing community-based services.”

The DSM-5, Potentially Too Fine-grained

In theory, DSM-5 seems a perfect method to categorize students’ mental health problems. But exact mental health labels are not always wanted or needed. Still, even though a specific diagnosis isn’t always required, some designation or recognized term is often needed. Without a common label, school psychologists may struggle to communicate and may struggle to organize their thoughts. As many school psychologists who have had practica or internships in clinical settings can attest, to-the-letter use of DSM-5 is less common than might be expected. In fact, in many multidisciplinary settings (e.g., those staffed by psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers) a precise DSM-5 diagnosis almost never appears when professionals speak to one another. Instead, if a mental health disorder seems to be present, it is typically referenced with a more general term than those found in DSM-5. It is as if the members all implicitly agreed on a list of prospective disorders. The commonly used list among this group might be something like this.

- attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- behavior disorder

- anxiety

- obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- depression

- bipolar disorder

- psychosis

- autism

- post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- eating disorder

- tics/Tourette syndrome

As you will see when cases are reviewed in upcoming chapters, a simplified scheme like this comprising just a dozen or so categories works pretty well for most practical purposes. For example, a general term, like anxiety, is sufficient to describe a working diagnostic hypothesis. As she first thinks about her case, a school psychologist need not concern herself with DSM-5’s many anxiety sub-distinctions (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, etc.). Instead, anxiety can serve as a placeholder until (or if) a more precise category is needed. In other words, if needed, she can zero in on an exact type of anxiety disorder by using DSM-5’s nomenclature and its explicit diagnostic criteria. Alternatively, she may find that the broadly encompassing notion of anxiety alone proves sufficient to allow her to answer the referral question and plan for the student via this obviously nomothetic approach.

You will see in Chapter 5 that many broadband rating scales (e.g., BASC-3) choose simplified and general terms like the 11 listed above. Your Skills Workbook includes examples to help clarify these generic mental health classification terms and convey how they align with DSM-5’s complex, precise system. For now, it may be helpful to examine Table 1.1, which lists some common mental health terms, their key features and their correspondences to particular DSM-5 diagnoses. If you have no familiarity at all with DSM-5, then reading the pages associated with some (or all) of the diagnoses listed in Table 1.1 might be illuminating. DSM-5 page numbers appear in the second column for the majority of the mental health disorders found in routine practice with youth.

Table 1.1 Generic Mental Health Categories and Their Correspondence to DSM-5 |

|

| Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) | |

| Features: | impulsiveness, hyperactivity, poor attention, disorganization, forgetfulness |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | ADHD-combined presentation; ADHD predominately inattentive presentation; ADHD-predominately hyperactive/impulsive presentation (p. 60) |

| Comorbidities include: | SLD, behavior problems, tic/Tourette |

| Behavior problem | |

| Features: | Non-compliance, defiance, |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | Oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder |

| Comorbidities include: | ADHD |

| Anxiety | |

| Features: | worry, fears, panic, avoidance, nail-biting, sleep problems |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | separation anxiety disorder (p. 190); selective mutism (p. 195); specific phobia (p. 197); social anxiety disorder (p. 202); panic disorder (p. 209); agoraphobia (p. 217); generalized anxiety disorder (p. 222) |

| Comorbidities include: | depression |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) | |

| Features: | perfectionism, over-focus on details; checking behavior, ritualism, scrupulousness, strong preferences |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | OCD (p. 237); body dysmorphology disorder (p. 244); hoarding disorder (p. 247); trichotillomania (p. 251); excoriation disorder (p. 254) |

| Comorbidities include: | anxiety, depression; bipolar |

| Depression | |

| Features: | moodiness, irritability, emotional outbursts, sadness, rumination, poor self-esteem, anhedonia, sleep and appetite problems |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | persistent depressive disorder (p. 168); disruptive mood disorder (156); major depressive disorder (p. 160) |

| Comorbidities include: | anxiety, (for disruptive mood disorder) behavior problem, autism |

| Bipolar | |

| Features: | bipolar I disorder (p. 123); bipolar II disorder (p. 131); cyclothymic disorder (p. 139) |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | mania, grandiosity, impulsivity, risk taking, irritability, depressed mood, sleep and eating changes |

| Comorbidities include: | ADHD, anxiety, behavior problem |

| Psychosis | |

| Features: | delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thinking, functional and communication regression |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | schizophrenia (p. 99); schizoaffective disorder (p. 105); delusional disorder (p. 90); brief psychotic disorder (p. 94) |

| Comorbidities include: | anxiety, OCD |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | |

| Features: | troubling and recurring memories, flashbacks, recurring and intrusive thoughts, concentration problems, visceral reactions, avoidance |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | PTSD (p. 271); acute stress reaction (p. 280) |

| Comorbidities include: | depression, anxiety |

| Eating disorder | |

| Features: | binge eating, extremely restricted food intake, self-induced vomiting, use of laxative for weight control, distorted body perception |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | anorexia nervosa (p. 339); bulimia nervosa (p. 345); binge eating disorder (p. 350) |

| Comorbidities include: | anxiety, depression, bipolar |

| Tic/Tourette syndrome | |

| Features: | motor and vocal tics, coprolalia, echolalia |

| DSM-5 diagnoses include: | provisional tic disorder, persistent tic disorder, Tourette’s disorder (p. 81) |

| Comorbidities include: | OCD, ADHD |

The Nomothetic vs. Idiographic Distinction in Practice

A real-world challenge confronting all school psychologists is the execution of thoughtful assessments. You probably already know that there is no singular, standard social-emotional evaluation (many techniques are available for your selection). Equally important, there are alternative assessment perspectives. Let’s return to the case of Rusty. His school psychologist used a classroom observation as one tool in her assessment. But why did her plan include an observation? What was she looking for and how did she hope to find it? Although many school psychologists conduct classroom observations, few consciously ask themselves questions like these. Instead, often, an observation is employed as one tool in a battery of techniques that never changes. Some school psychologists, for example, perform structured time sampling as their routine observation method. Looking at discrete time intervals (as you will learn in Chapter 8) is a great way to search for antecedents and consequences. Antecedents and consequences might explain behavior, but they do so from an idiographic perspective. In the case of Rusty, however, the school psychologist’s interests were largely nomothetic (the prospect of ADHD or ODD, or both). Because direct classroom observations can adopt either nomothetic or idiographic perspectives (Volpe & McConaughy, 2005), in each case it is important to intentionally match the observation strategy with the corresponding big-picture assessment orientation. In Rusty’s case, an observation tool that deals with categories of adjustment in a norm-referenced way (like the ASEBA Direct Observation Form; McConaughy & Achenbach, 2009) might have been better strategy than counting the number of intervals that Rusty was off-task or on-task. The Direct Observation Form enables nomothetic interpretations (e.g., standardized information about attention problems). This is just what Rusty’s case called for. You’ll learn much more about clear thinking enabled by the nomothetic vs. idiographic distinction in the chapters to follow.

Components of Social-emotional Assessments in Schools

It’s time for a first look at the various elements of assessment. Listed below are the most common assessment components executed by school psychologists (also see Table 1.2). Boundaries may be nebulous, and one component might overlap another. Not every component need be used in every case. And, as you might suspect, some components yield more usable information in some cases, whereas other components yield more usable information in other cases.

Referral and Referral Agent Interview

The referral question is covered in Chapter 3. Often, but not always, one or more teachers would be interviewed during this stage. If not at this point early in the process, teacher(s) would be interviewed later.

Informed Consent/assent

Informed consent by parents or guardian is required for ethical and legal reasons. Each school district has its own forms to be signed before the formal assessment process begins. Older students agree (assent to) being assessed also.

School Information

This is a multi-faceted category that varies from setting to setting and from student to student. Under this broad heading, each student’s “Cumulative Record” or “Cumulative Folder” (often available via a district-level data management system) typically includes information on attendance, report card marks, discipline referrals, standardized group achievement test scores, data on academic probes, as well as teachers’ commentary. Also falling in this category are health records, such as may be stored in a school nurse’s office (including information on hearing and vision screenings and medicines prescribed for administration during school hours). When special education records exist, they warrant review. So-called “permanent products,” which consist of worksheets and written exams retained by teachers, are also typically considered part of the record review process.

At this time also, school psychologists routinely interview the students’ classroom teacher(s). If the teacher herself did not launch the referral, then she would be interviewed at this stage rather than earlier. Teacher interviews can start with general questions about academics, social status, work style, attention, mood, anxiety, and behavioral consistency from day-to-day depending on the relative emphasis of nomothetic and idiographic perspectives. More specific questions can follow based on a school psychologist’s emerging hypotheses about the apparent nature of the student’s problem.

Review of Home and Developmental Data (and Parent Interview)

In many school settings, parents complete a standardized form entitled “history and development,” “special services review,” “parents’ questionnaire,” or something similar. No matter how titled, this form typically addresses a child’s health status, her development, standing within the family and neighborhood, as well as affording parents a chance to make open-ended comments. Unfortunately, speaking directly with parents only occurs sometimes. Whereas teacher interviews are almost universally done face-to-face, any parent interviews might be done by telephone. If parents have completed a standardized history and developmental form, the school psychologist at this stage might ask for clarification or elaboration. As with teacher interviews, after initial rapport building, conversations might turn to general questions covering potential concerns, followed by increasingly focused inquiries, depending on emerging hypotheses. As you will see in Chapter 4, the tandem process of reviewing school records and tapping parents’ information, cumulatively referred to as “Background Information,” can provide the school psychologist with vast information.

Broadband Rating Scales

When researchers recently conducted an analysis of test instruments used by school psychologists, they confirmed what many people already expected—broadband rating scales topped the list (Benson, Floyd, Kranzler, Eckert, Fefer & Morgan, 2019). For example, various versions of the BASC-3 (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015) held the top spot as well as other locations in the top 10. Used daily by many school psychologists, broadband rating scales often enjoy a central role in school-based social-emotional assessments. This is because broadband rating scales tap many areas of potential psychopathology, social skills and peer interactions, plus adaptive functioning. Their administration requires little or no professional time. What’s more, broadband scales can be completed by various informants, such as teachers and parents (see Chapter 5) as well as the student herself (see Chapter 6), affording multiple perspectives and fueling their popularity. As you will learn, the psychometric sophistication of these diverse tools further boosts their popularity.

Observation and Interview of Student

Student observations can range from highly structured procedures conducted on one or more occasions in a classroom to unstructured classroom observations in which school psychologists simply jot down anecdotes. This was already implied in the case of Rusty. Also, typically included are observations during face-to-face meetings or in the midst of psychometric testing. Sometimes included are characterizations of the youngster’s physical presentation and his/her grooming. As with use of the other assessment components mentioned above, direct observations can often help generate, support or refute working hypotheses. Chapter 8 provides detailed information about observations conducted in schools.

Student interview techniques range from highly structured, detailed, and time-consuming psychiatric interviews to those that are unstructured, brief, and ad hoc. These realities were evident when Amy Garcia and Jack Bolden interviewed their respective students. Like the other assessment components, interviews are modified to fit concerns that either existed at the time of initial referral or became pressing as various information was gathered during the multi-stage assessment process. Chapter 9 contains in-depth guidance for learning to conduct interviews.

Narrowband Scales

In concert with broadband rating scales, narrowband scales focus on a particular concern, such as anxiety or depression or ADHD. You can envision the nomothetic possibilities evident in broadband and narrowband scales because these tools enable comparing one student with a group of many other students. In contrast to broadband scales, their narrowband counterparts are typically used when the assessment has move to a narrow focus. Thus, emerging hypotheses determine which if any narrowband scales are employed. As you will learn in Chapters 7, instruments in this category permit ratings by parents, teacher, as well as a student herself.

Table 1.2 Sequence of Typical Social-Emotional Assessment Tasks |

|

| Initial Stage | |

| A. Referral (and referral agent interview) | |

| B. Informed consent/assent | |

| Middle Stage | |

| A. Review of school data (and teacher interview, if necessary) | Elements of the middle stage can be modified to meet case demands |

| B. Review of home and developmental data (parent interview) | |

| C. Use of broadband rating scales | |

| D. Observation and interview of student | |

| E. Use of narrowband rating scales | |

| Final stage | |

| A. Written report | |

| B. Oral report | |

Written and Oral Reporting

There are a host of practical, ethical, and legal considerations that appear at the conclusion of the assessment process. These concern oral reporting to parents and, in the case of school-based assessments, other team members. Findings also need to be organized for clear reading so that they can be stored and accessed when needed. These topics are covered in Chapter 13.

For Each Case, Use Only Necessary Tools

It is self-evident that routine use of every one of these assessment components would take a lot of time. This is true although many sources imply (or say overtly) that every tool is needed in every case. But consider the case of Angela. A fifth-grade teacher approaches you about a student of hers, Angela, suspected of having underdeveloped social skills. Despite her teacher’s concerns, Angela is a strong student, with regular attendance, and someone who never disrupts in class or causes problems on the playground. Further, she consistently scores well on high-stakes tests. Other than currently having just one friend, there is nothing seen in class to suggest much of a problem, including presence of a DSM-5 condition. Angela’s teacher later clarified that her actions were prompted by Angela’s parents who are contemplating starting their daughter in an out-of-school social skills program. They reportedly confided to her teacher that their daughter is chronically “socially confused.” When you, the school psychologist, eventually speak with Angela’s parents, they ask if you would verify or refute the prospect of genuine social skills problems. It seems likely that enrollment in the social skills program hinges on your confirmation of faulty social skills development. If you decide to help out, should your plan include gathering, scoring, and interpreting rating scales from teacher, parents, and Angela herself coupled with classroom observations, parent interview, and face-to-face interview with Angela? It can be argued that the answer is “probably not.” An evaluation that expansive fails to fit the needs of Angela’s case.

Here is the crux of the “probably not” position: although using all categories of assessment tool is often advisable, it is not always advisable. There are several factors that support the “no” decision. First, Angela’s potential problem is ill-suited to several of the proposed assessment techniques. Pouring over her school records for authentication of a social skills problem is likely to prove futile. So too for self-report rating scales. For example, the self-report version of the Conners Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scale (Conners CBRS; Conners, 2010) includes no scores related to social skills. In contrast, parent and teacher Conners CBRS options do (entitled Social Problems). Why use something (i.e., a self-report instrument) that fails to address the referral question?

A second reason for forgoing the full assessment arsenal is more practical. It involves “cost-benefit” considerations. These are critical considerations that busy practitioners wrestle with daily. How much effort and time (cost) is expended should be weighed against positive outcomes (benefit). This is so because schools typically retain too few psychological resources to satisfy all of their psychological needs. Cases like Angela’s risk misallocation of resources if they use lock-step assessment batteries. To this point, a number of years ago the entire time expenditure associated with a psychoeducational evaluation was tabulated. The median value was a surprisingly large 11.7 hours, prompting the researchers to warn, “….it is not always the case that more is better. A more-is-better philosophy could result in an imbalance between the time devoted to individual assessment and to other professional activities that fall within the realm of school psychology (i.e., counseling and other direct services, consultation….” Lichtenstein & Fischetti, 1998, p. 147). For Angela, it might make sense to avoid throwing the kitchen sink at the problem, instead opting for a tailored assessment (see Abrams et al., 2019). As a concession to skeptics, it is true that in an ideal world, blessed with unlimited resources, it might be better to complete each and every assessment component during every single assessment. School psychologists, however, do not inhabit that idealized world.

A third reason for saying no to using every component in cases like Angela’s is more technical. Later we will cover the notions of over-identification and under-identification and how these considerations help set threshold levels for diagnostic decisions. Simply put in Angela’s case, judging social skills deficits to be present (when they are actually absent) so that social skills training can start hardly constitutes a huge mistake (a false positive probably isn’t that detrimental). After all, how problematic is contact with a competent counselor, even potentially superfluous contact? Moreover, the off-campus nature of the proposed social skills services (free of classmates’ awareness) further contraindicates the prospect of harm. In general terms, social skills judgments about Angela constitute a relatively low-risk, low-stakes decision, well suited to low-intensity assessment practices. This contrasts with high-stakes decisions (e.g., special education eligibility), the very bread and butter of many school psychologists’ practice. There is nearly universal support for using all assessment components for high stakes decisions.

Dimensional versus Categorical Distinction

Some of the tools mentioned above, of course, involve scores. The scores, which allow an individual student to be compared with representative age-peers (and sometimes gender-peers), are invaluable. You will recognize this as inherently nomothetic. For example, the BASC-3 (a broadband scale) allows students to be characterized on as many as 30 dimensions (e.g., anxiety, depression, attention problems, atypicality). Similarly, the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-2nd edition (BRIEF-2, Gioia, Isquith, Guy & Kenworthy, 2015), a narrowband scale, permits characterization on just executive function. Both of these measures use standard scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10; these are T-scores. Crucially, T-score values can be used in two related, but nonetheless distinct, ways.

One approach is dimensional. Jing Wang, a school psychologist who serves a large high school, has assessed a 17-year-old boy referred by her colleague, a school counselor. The counselor expressed concern that this seemingly bright youngster remained a marginally student. Before selecting any rating scales for use, Jing reviewed background information and spoke to the student’s teachers. In light of two teachers’ seemingly mixed messages about this boy’s study skills, Jing administered the BRIEF-2 to assess executive functioning. Jing recognizes that her school imposes steep requirements for organization because each student must enroll in six academic classes and each class demands completion of extensive homework. Competent executive functions might be needed, and she wondered where this boy would score. It turned out that this youngster had a BRIEF-2 composite T-score of 52 from one teacher and 49 from another (both scores are close to the T-score mean of 50). Jing was hoping that this student possessed strong BRIEF-2 scores so that his executive function would serve as an asset. The results, however, suggest that executive function is probably neither a liability nor an asset. Jing used the BRIEF-2 scores dimensionally. She envisioned a capability continuum related to executive function with each student placed along a continuous range of possible scores.

Another approach is categorical. Let’s assume that Jing also developed concern about a mental health possibility–depression. Her use of the BASC-3 might help her resolve concern about this possibility. This is so because the BASC-3 includes a scale devoted to measuring depression. In this instance, however, Jing is not thinking of depression primarily as a continuum. That is, she does not envision the BASC-3 as measuring a spectrum of mood with one end anchored by “happy/self-satisfied” and the other anchored by “depressed/unhappy.” Instead her conceptualization can be thought of as the binary answer to the following question—is depression present or is it absent? Attempting to answer this question with the BASC-3 would certainly involve studying the student’s depression score but the real focus would be around some cut-score value. For example, BASC-3 T-scores above 70 are said to fall in the clinical range. Scores this extreme help to confirm the presence of a condition, such as depression. But it turns out that this particular student’s BASC-3 Self-report T-score was 56. This “average range” score implies that the answer to the binary depression/no depression question is “no depression.” When thinking categorically, Jing is unlikely to weigh variations along a continuum. In other words, she won’t think that a T-score of 44 is practically different than a T-score of 56. This is true because neither of these scores suggests that depression is present, and that is her circumscribed mission when she operates categorically.

The dimensional/categorical distinction may bring to mind the nomothetic/idiographic distinction that you read about earlier in this chapter. Like that distinction, this one can also help to sharpen your thinking. In practice, referral questions and your evolving case conceptualization will determine which approach to follow. At times, you might start by looking at scores dimensionally, looking for relative strengths or weaknesses. But you may end up thinking categorically, perhaps because the possibility of a mental health problem pops up on one or more dimensions of a broadband scale. Often, a thorough job will involve complementary considerations of both dimensional and categorical perspectives. Familiarity with both, like familiarity with the nomothetic vs. idiographic distinction, helps assure each viewpoint receives the attention it warrants.

Relax: Dimensional Interpretations Often Use Familiar Measurement Concepts

Critically, score interpretation cannot proceed in the same way for these two approaches. Dimensional interpretations are likely to be the most familiar. This is because interpreting a trait like anxiety is akin to interpreting a continuous trait (or ability) like IQ. Standard scores convey the best estimate of each individual’s location on a continuum. Classical test theory suggests that there is also a hypothetical “true score” but this score is inherently unknowable (Bandalos, 2018). Instead, the observed scores we examine in our practice represent estimates of true scores. As you may already know, we routinely create a confidence interval around an observed score to help us judge the likelihood that the true score falls within a specific range. For Jing, her student’s BASC-3 depression score of 56 can also be described as 56 +/- 6.8. The chances are 95% that this student’s true depression score is between 49 and 63 (according to tables provided in the BASC-3 manual, p. 231).

When it comes to score validity for dimensional interpretations, traditional approaches are used. They too are likely to seem familiar to most school psychologists. For example, research determining the validity of a new “hyperactivity-impulsivity” scale may involve correlations with a recognized hyperactivity-impulsivity scale. All scores from two distributions would be correlated. A high correlation implies that the dimension of hyperactivity-impulsivity scores in one test’s distribution agrees with the dimension of hyperactivity-impulsivity in another test’s distribution. This is criterion validity. Other patterns of correlation among tests with the same and different constructs might also be studied (construct validity). All items on a test might also be scrutinized to see if their content matches the intended construct (content validity). If concepts related to reliability, including standard error of measurement (SEM), and validity are unfamiliar, you may need to do some supplemental reading to prepare for the material in this book. Here are a few published sources that might help you: Bandalos (2018), Kaplan and Saccuzzo (2013), Sax (1997). Alternatively, your instructor might add measurement-related details when you reach Chapters 5, 6, 7, 11, and 12 (points in the book where test score interpretation becomes especially important).

Caution: Categorical Interpretations May Use Unfamiliar Measurement Concepts

Now comes a very important, but frequently overlooked, point–the familiar types of validity you just saw regarding dimensional interpretations are not particularly helpful for categorical considerations. It is one thing to determine that two tests’ scores are correlated (i.e., associated across two entire distributions). It is quite another thing to determine that scores on two tests would place the same individuals into discrete categories (e.g., classification of children with ADHD vs. those without ADHD). Thus, when using the categorical perspective, correlational evidence of criterion validity does not prove much. For categorical purposes, a different type of validity is needed. This is sometimes referred to as “classification validity.” For example, consider the following directive: “Rather than calculating correlations, classification validity is examined by comparing the number of individuals identified as exhibiting (and not exhibiting) problems on a ‘gold standard’ test (i.e., true positives and negatives)…” (Nelson, 2008, p. 542). Because much of this terminology may be unfamiliar to school psychologists, let’s first breakdown this important statement. Then let’s look very concretely at an example of researchers studying classification by using a psychometric test. This will allow us to do something else important–examining classification statistics more generally. We will see in many places later in this book that classification validity is essential. Thus, it’s worth taking the time to become familiar with it here. A warning is in order. If this is your first exposure to these concepts you will probably need to read slowly, make margin notes or highlight, and then reread. You might also want to watch one or more of the many videos on the topic. I’ve included a link to one of these below. Later, you will discover that your effort pays practical dividends.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sg6NKj3fYHM

Diagnostic Utility Statistics and Classification

Classification validity hinges on concepts subsumed under the broader category of diagnostic utility statistics. Cumulatively, the terms you are about to hear (especially sensitivity and specificity) are considered to be diagnostic utility statistics. But let’s start by reconsidering element-by-element Nelson’s statement about classification validity that you just read.

A gold standard means an agreed upon (best possible) method of establishing whether a disorder is present. For example, researchers might adopt as their gold standard an extremely thorough and time-consuming evaluation. Such an evaluation is often too complex or too expensive to routinely replicate in the real-world. This might be a gold standard method of diagnosing ADHD, for example. With a gold standard like this available, it becomes possible to do something critical. That is, to quantify the degree of agreement between the determinations made via the recognized gold standard compared to those made by another test. This other test, such as a new (candidate) test of ADHD, might ultimately be used in practice instead of the gold standard. Quantification will occur by looking at one research participant’s scores after another and establishing for each if the decision made by a candidate test and the decision made by the gold standard agree or disagree.

Now some essential terminology: A “true positive” indicates when the candidate test is positive and the individual actually has the disorder (as established by the gold standard). Correspondingly, a “true negative” indicates when the candidate test is negative and the individual does not have the disorder (as established by the gold standard). As you might suspect, however, researchers sometimes discover that an individual’s candidate test score and reality (what the gold standard says) disagree. These classification mistakes are called “false positive” when candidate test results are positive but in reality the disorder is absent. They are called “false negative,” when candidate test results are negative but in reality the disorder is present.

This may seem abstract. So let’s look at a published research study that actually concerned classification validity to make things more concrete. Table 1.3 summarizes the use of a diagnostic test (Cognitive Assessment System, CAS; Naglieri & Das, 1997). In this study, the CAS was used to classify students as likely to have or unlikely to have ADHD. The research was conducted at Eastern Illinois University by school psychology professor Gary Canivez and his student, Allison Gaboury (2015). The researchers’ precise rubric for making a cut-score on the CAS is not important for our current general purposes, nor is the methodology for establishing a gold standard ADHD diagnosis. Instead, we just want to become acquainted with the 2 X 2 grid depicted in Table 1.3. Work down the left column in Table 1.3 from top to bottom (i.e., under the column entitled “Disorder is present”). How well did the CAS work in classifying these 20 individuals with ADHD? It turns out that 16 of the 20 with ADHD were correctly classified by the CAS (these 16 are the true positives). Now look one column to the right and repeat the process for the 20 participants who according to the gold standard were free of ADHD (i.e., under the column entitled “Disorder is absent”). This time, 15 of the 20 without ADHD were correctly classified (these 15 are the true negatives). Researchers, as well as their field-based colleagues, invariably want findings like this simplified, such as by use of a simple percentage. The success of the CAS as a candidate test in correctly classifying those with ADHD is referred to as “sensitivity.” Sensitivity is simply the number of correctly classified participants with ADHD (i.e., true positives) divided by all participants with ADHD. In this study the sensitivity is 16/20 or .80. Specificity is equally simple. It is merely the number of correctly classified participants lacking ADHD. Specificity in this study is calculated to be .75 (i.e., 15/20).

Table 1.3 Canivez and Gaboury’s Raw Data Regarding ADHD Classification |

|||

| Pre-existing (gold standard) ADHD diagnosis

|

|||

| Disorder is present n = 20

|

Disorder is absence n = 20

|

||

| Current CAS test results |

Positive

|

16 | 5 |

|

Negative

|

4 | 15 | |

Now check out Table 1.4. It is essentially the same as Table 1.3 but without numbers. Table 1.4 does, however, include a simplified formula to support calculating percentages. It also gives you terms. Revisit this table whenever diagnostic utility statistics become confusing. You might notice two new terms in Table 1.4: “Positive predictive value” and “Negative predictive value.” Don’t be troubled by these now. They involve what would happen if researchers worked across the table’s columns rather than down its rows. Positive predictive value indicates how many individuals (percentage wise) with a positive score were correctly classified in this study. Similarly, negative predictive value indicates how many individuals (percentage wise) with a negative score were correctly classified in this study. But there would be a problem translating these number to your applied practice. This is because the rate of individuals with ADHD in this study (50% of participants had ADHD and 50% did not) is unlikely to match the rate of ADHD where you practice. Because mismatches like this between research and applied practices is common, trusting Positive and Negative Predictive for practice considerations is not generally advised

You will hear more about the important notion of base rate (the percentage of individuals with a particular condition that might exist in your practice setting) in the next chapter. For now, just concentrate on the notions of sensitivity and specificity. The Skills Workbook contains exercises to augment your understanding of sensitivity and specificity. Also note that free, online programs such as those on by medcalc can perform calculations https://www.medcalc.org/calc/diagnostic_test.php.

Table 1.4 Diagnostic Utility Statistics, a General Rubric |

||||

| Gold standard (or reality) | ||||

|

Disorder is present

|

Disorder is absent |

|||

| Test results |

Positive |

(A) true positive |

(B) false positive |

“Positive predictive value” A /A + B |

|

Negative |

(C) false negative |

(D) true negative |

“Negative predictive value” D / C + D |

|

|

“Sensitivity” A /A + C |

“Specificity” D /B + D

|

|||

A skeptic might ask if diagnostic utility statistics (like sensitivity and specificity) are actually part of contemporary school psychology practice? The answer appears to be “yes.” The very method depicted in Table 1.4 for calculating sensitivity and specificity is applied hundreds of times each year across surprisingly diverse fields. These include studies conducted in industry, medicine, economics and psychology. School psychology has progressively joined in. This is evident in recent studies on the following topics: literacy (Van Norman & Nelson, 2019); universal screening (Kilgus, von der Embse, Taylor, Van Wie & Sims, 2018); the cross-battery approach for SLD identification (Kranzler, Floyd, Benson, Zaboski & Thibodaux, 2016); the Devereux Student Strengths Assessment Mini (Shapiro, Robitaille, Kim & LeBuffe, 2017) and students who suffer social rejection (McKown, Gumbiner & Johnson, 2011).

Even more relevant to daily practice, many test manuals now report practitioner-friendly sensitivity and specificity information. These include both broadband scales and narrowband scales. Regarding broadband scales, the Conners Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scale (Conner CBRS) manual provides such sets of sensitivity and specificity facts (Conners, 2010). Regarding narrowband scales, sensitivity and specificity information is found in manuals of instruments that assess ADHD (the ADHD-5 Rating Scale; DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulous & Reid, 2016), autism (the Autism Spectrum Rating Scale; Goldstein & Naglieri, 2013), and depression (the Reynolds Child Depression Scale-2; Reynolds, 2010), as examples. Even manualized diagnostic child interviews sometimes provide sensitivity and specificity information (e.g., MINI-KID; Sheehan et al., 2010). Moreover, there is a growing body of peer-reviewed literature that examines the sensitivity and specificity of instruments after their publication. Although not appearing in instruments’ manuals, this post-publication research adds to the body of material available to practitioners when making categorical decisions. Some examples are the Child Behavior Checklist’s ability to detect anxiety (Knepley, Kendall & Carper, 2019), the Child Behavior Checklist and the Conners Continuous Performance Test to detect ADHD (Jarrett, Van Meter, Youngstrom, Hilton & Ollendick, 2018), the Child Behavior Checklist to detect ADHD (Edwards & Sigel, 2015), the BASC-3 to detect ADHD (Zhou, Reynolds, Zhu, Kamphaus & Zhang, 2018), the BASC-2 to detect autism (Bradstreet, Juechter, Kamphaus, Kerns, & Robins, 2016), the Devereux Scales of Mental Disorders regarding emotional disturbance (Reddy, Pfeiffer & Files-Hall, 2007).

In light of these facts, it’s hard for school psychologists in today’s world to engage intelligently in categorical decisions if they know nothing about sensitivity and specificity. As you will see repeatedly in the chapters ahead, there are times when school psychologists indeed use categorical designations (and clinical labels) to their advantage. Doing so sometimes is indispensable to understanding a student and intelligently planning for her. You will also see two instances, autism (Chapter 11) and ADHD (with possible OHI designation; Chapter 12), where clinical labels allign closely with categories used for special education qualification. In all of these instances, classification validity proves to be the proper means for making sense of students’ scores.

Caution: Traditional Statistics are Ill-Suited for Classification Validity

When you consider test scores for classification, diagnostic utility statistics (sensitivity and specificity) can be quite illuminating. Unfortunately, test manuals sometimes provide only feeble alternatives, such as reporting evidence of “statistically significant” group differences (e.g., between test scores for children with and without a particular diagnosis). Let’s look at a simple example that will begin to flesh out the problem of having only generic statistics when judging whether a test is any good at classification. Later we will look more concretely at the limitations of group level statistics for school psychologists in actual practice (in this case, a question about autism).

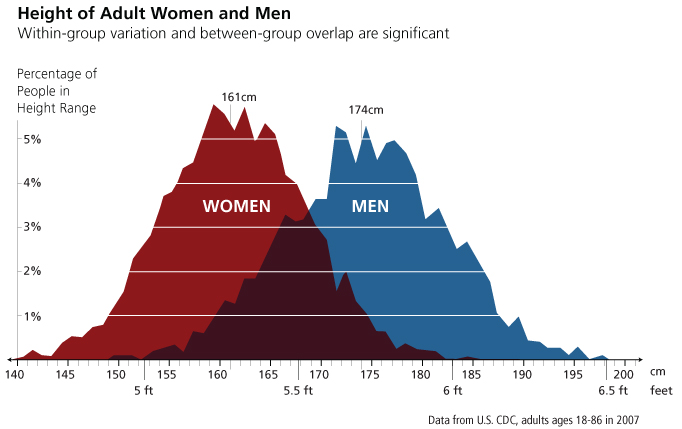

On average, men and women differ in height. Figure 1.2 depicts a distribution of women’s heights on the left and men’s heights on the right. Researchers could tap these two naturally occurring groups to conduct a statistical analysis, such as an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or student’s t-test (Warner, 2013). This could speak to the issue of whether the two groups differ overall. It’s no surprise men’s average height exceed women’s average height at a statistically significant level (e.g., p < .001). This confirms that the two height distributions were unlikely to have arisen from chance alone. But critically, the ANOVA results fail to inform us whether height could be used to predict gender in individual cases. Here’s the key point: differences between group means (as documented by statistical significance) is usually not much help for making categorical decisions (Bandalos, 2018).

Again, look at Figure 1.2. Although it is true that the two group means differ, women’s and men’s distributions also overlap. And it’s easy to commit the error of “neglect of overlap” (Meehl, 1973). For example, there are a few men whose height is 64.0 inches and a lot of women whose height is 64.0 inches. In light of this fact, you can imagine the situation confronting someone blinded to actual gender who was provided a single individual’s height of 64.0 inches and obliged to identify whether this number signifies the presence of a man or a woman. The best bet is a woman. But predicting a woman would turn out to be occasionally wrong. On the other hand, predicting a man would turn out to be frequently wrong. Unfortunately, how occasionally wrong for predicting a woman and how frequently wrong for predicting a man remains completely unknown. In general, of course, the more statistically significant the better (this implies that the group means are relatively far apart). But only diagnostic utility statistics are typically of practical value when confronting categorical decisions (the exception would be in the remote occurrence of two utterly non-overlapping distributions).

The limitations of group-level data for categorical decisions was spoken to more than 60 years ago by Meehl and Rosen. Here was their mid-century complaint “results are frequently reported only in terms of significance tests for differences between groups rather than in terms of the number of correct decisions for individuals within groups” (Meehl & Rosen, 1955, p. 194). Back then, when the country was full of girls with poodle skirts and boys with ducktails, t-test results and probability values were commonly highlighted in test manuals and research publications in lieu of sensitivity and specificity values. Fortunately, things have improved somewhat. Even today, however, school psychologists sometimes look in vain for diagnostic utility statistics among the pages of test manuals. Perhaps this is why Watkins echoed Meehl and Rosen’s assertion in a chapter designed to hone 21st century school psychologists’ critical thinking, “…school psychologists should not confuse classical validity methods with diagnostic statistics…group separation is necessary but not sufficient for accurate decisions about individuals” (Watkins, 2009, p. 221). You will see plenty of examples in this book of school psychologists’ assessment procedures that do report and do not report diagnostic utility statistics

If you sense that things are not always what they seem to be in the world of assessment, you are correct. Observed scores are not the same as true scores, reports of statistical significance may fail to substantiate true significance, and using test manual cut-scores (e.g., T-score = 70) inevitably produces some misclassification. Intuition and common sense only go so far. In fact, there is a vast field of empirical research that addresses this topic—humans’ tendency to make errors of judgment and to construe the world as it “seems to be” rather than as it is. Because so much of assessment involves analysis and judgment, knowing about these universal tendencies to distort reality is essential. That is the topic you will read about in Chapter 2. Chapter 2 will finish with practical, tangible ways to minimize errors during your assessment practices. Specifically, you will learn about a worksheet that can be used in all of your social-emotional cases, a sophisticated method of estimating the likelihood of various conditions, plus an introduction to the use of practice friendly checklists.

Summary

This chapter covers several important considerations for conducting social-emotional assessments in school settings. Several of these comprise important distinctions or contrasts. One such contrast is between an assessment prospective concerned with an individual student’s uniqueness and an alternative perspective that concerns individuals as members of a group about whom much is already known from psychological research. The former approach is termed idiographic, the latter nomothetic. Another distinction is between types of labels, some of which are administrative in nature (and often concern special education gatekeeping) and others of which are clinical (designed to understand homogeneous groups of children, such as those with a particular mental health condition). Other distinctions concern interpretation of psychological instruments. For example, one interpretation approach addresses a continuum of test scores whereas another addresses discrete categories (i.e., those with a condition vs. those without that condition). The latter is particularly important because it lead us to the need for specialized statistics, such as sensitivity and specificity. Relatedly, if psychological tools are used to make categorical distinctions, then test publishers ought to report evidence of classification validity. As you will see in the chapters ahead, they sometimes fail to do so.