16 Projective Techniques: Even We Skeptics Should Know a Little

Key takeaways for this chapter…

- With their open-ended nature, projective techniques represent a stark contrast with standardized psychometric instruments

- The most common projective techniques include storytelling (e.g., the Thematic Apperception Test, the Roberts-2), inkblots (the Rorschach), sentence completion techniques and drawings (e.g., the Draw-A-Person test)

- In general, projective techniques hope to reveal the unique aspects of personality (they are idiographic)

- Projective techniques are only suited to some referral questions

- Training in some projective techniques (e.g., sentence completion and story techniques) may promote “psychological mindedness” even if practitioners never use the techniques at their schools

- As producers and consumers of psychological test results, all school psychologists should expect to sometimes encounter projective test results

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- Jane, psychodynamics revealed by projective techniques

- Anna, the Thematic Apperception Test

- Bethany, the Thematic Apperception Test

- Carlita, the Thematic Apperception Test

- Danielle, the Thematic Apperception Test

- Roberto, the TEMAS

- Karen, the Rorschach

- DM, the Rorschach

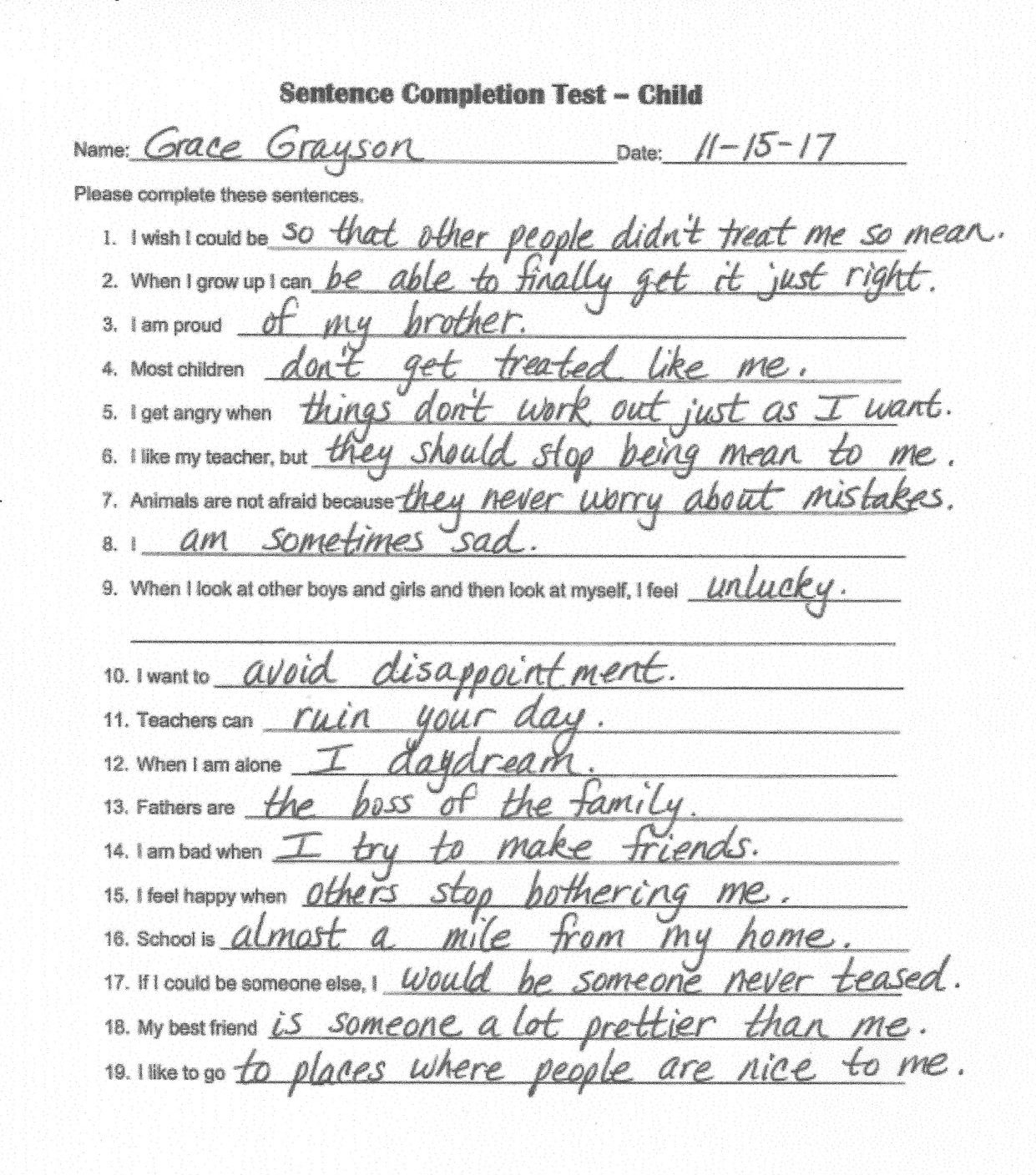

- Grace, the sentence completion

- Angelique LaRue, a school psychologist using projective drawings

Most school psychologists have at least heard about projective techniques. These involves things like storytelling (e.g., the Thematic Apperception Test; TAT), inkblots (i.e., the Rorschach), sentence completion techniques, and children’s drawings that are used to interpret aspect of social-emotional functioning. Furthermore, most school psychologists recognize that projective techniques are controversial and sometimes professionally polarizing. Many programs seem to reflect the widespread position that projective techniques are scientifically weak and out of step with today’s approaches to school psychology practice (Benson, Floyd, Kranzler, Eckert, Fefer & Morgan, 2020). A few school psychology programs emphasize them. In the former programs, if projective techniques are covered at all they may get mentioned for their historical significance as psychologists in the last century, including those working in schools, were discovering their professional identity and refining the tools that would ultimately define their practice. Although projective techniques were once overwhelmingly popular, by the mid-1980s there were already rumblings of discontent, exemplified by journal articles with titles like this: “School psychology and projective assessment: A growing incompatibility” (Peterson & Batsche, 1983). By the mid-1990s NASP members and faculty in school psychology programs confirmed dwindling interest. For example, a survey by Wilson and Reschly (1996) found that only about one-half of programs covered the TAT during supervision and just 35% did so in coursework per se. Today’s school psychologists probably can find colleagues residing in one of two contrasting camps: projective techniques are irrelevant (I never even consider them) vs. projective techniques are valuable (I use them routinely or at least sometimes when I want to understand unique aspects of a student’s personality). The second camp is decidedly smaller than the first. In light of this incongruence, this book provides enough coverage so that non-users understand the rationale, potential uses, and limitations of projective techniques. This level of familiarity is helpful when an outside report–one that includes projective techniques–arrives on campus. And, it provides those interested with a foundation should they later seek in-depth training.

Revisiting the Nomothetic and Idiographic Perspectives

Projective techniques often make more sense if they are contextualized in the nomothetic as contrasted with the idiographic perspective. Much of today’s practice world, and indeed the approach generally advocated in this book, can be characterized as objective, quantifiable, and behavioral. It is also largely nomothetic: concerned with general patterns and with categorization. To restate the obvious, typical rating scales use fixed, objective items that consist of identical questions and a common Likert system for item endorsement (i.e., not at all, occasionally, often, never). Items concern overt behavior (or at least overt actions that might or might not concern a covert problem [e.g., student seems anxious]). Item-level responses are converted to numbers (raw scores, T-scores) that compare a particular student with a representative group of other students. The dimensions on which students are compared (e.g., internalizing, externalizing problems) are derived from analysis of many, many students’ scores, not just a single student. Critically, one student is understood because they are contextualized within a group of other students. This permits fixed decision rules (cut-scores) and calculations of probabilities (e.g., probability nomogram and post-test probabilities). In fact, some aspects of school-based assessment might be viewed as akin to applied mathematics, human engineering, and organizational/industrial psychology. Even when standardized psychological measures per se are uninvolved, this approach still commonly undergirds psychologists’ thinking. After all, ADHD is defined by a set of universally adopted criteria; diagnosticians do not devise their own notion of ADHD based on personal understanding or clinical wisdom. These considerations are so intrinsic to contemporary school psychology practice, and so embedded in our daily language, that their presence may go unrecognized. If you followed most of the discussion found in this book’s earlier chapters, you understand this approach.

Consistent with the discussion above, Lilienfield, Wood, and Garb (2000) asked the big picture question: How much scientific evidence exists to support the applied use of projective techniques? Here is their conclusion, apparently unchanged during the ensuing years, “We conclude there is empirical support for the validity of a small number of indexes derived from the Rorschach and TAT. However, the substantial majority of Rorschach and TAT indexes are not empirically supported. Validity evidence for human figure drawings is even more limited” (Lilienfeld et al., 2000, p. 27). Thus, for school psychologists attempting to use the HR approach (see Chapter 2 for details), projective techniques are of limited nomothetic value. A TAT replete with themes of gloom and pessimism might suggest a nomothetic hypothesis like depression, but it does little to confirm it.

There is, however, a contrasting perspective for understanding students, the idiographic view. It concentrates on the uniqueness of every individual. As you will recall, users of the HR approach are urged to consider situational factors and the uniqueness of students’ experience as part of the assessment process. In other words, completing each stage of the HR Worksheet involves joint consideration of nomothetic as well as idiographic hypotheses. Although the idiographic approach encourages consideration of situational factors (how one school context might prompt a student to act out whereas another may not), it’s the internal not the external world that projective techniques address. Projective techniques are by their very nature less structured, more open-ended and more dependent on the judgement and insights of a highly-trained clinician.

When teamed with psychodynamics (Freudian interpretations of human behavior), the idiopathic perspective provides the historical foundation for projective techniques. Considering just a few psychodynamic principals illuminates their relationship with projective techniques. According to a simplified version of Freud, humans are understood by appreciating the complex interplay of three hypothetical psychological structures. These are Sigmund Freud’s famous id, ego, and superego (Storr, 1989). Mental life and overt behavior is largely the admixture among urges toward action (id = primitive and immediate), modulation of those urges (ego = testing reality and defenses against impulse control and threats to self-perception or positive self-esteem), and weighing the appropriateness of urges (superego = moral rights/wrongs and internalization of cultural values). Critically, each individual’s conflicts play out largely unconsciously (e.g., unrecognized struggles between acting out and controlling impulses or between submitting to parental authority or rebelling against it). This means fixed behavioral rating scales and structured behavioral observations may afford psychologists only a partial picture. That is, objective rating scales may be entirely too rigid to illuminate unique aspects underlying children’s perceptual and emotional world. Perhaps children themselves are unaware of the origins of their actions; they may fail to know why one course of action was selected over another. If this is true, child interviews might risk providing limited and (sometimes) inaccurate information. Asking an aggressive student why they hit a classmate makes no sense if the student is unaware of the genesis of their actions. Comparable, or more severe, limitations may plague objective self-report measures. Equally troubling, informant-completed checklists and questionnaires necessarily involve circumscribed inquiries about students’ actions. Informants are arguably in no position to reveal the perceptions, conflicts, coping styles, and values unique to just a single student.

The distinction between the nomothetic and idiopathic approach is reflected in a case contained in Blackham’s text The Deviant Child in the Classroom (1967). Garth Blackham was a practicing school psychologist who became a university professor, researcher and author. Like many of his contemporaries in the 1960s, Blackham was a clinical psychologist working in schools. His case of “Jane,” a girl with several physiological illnesses and poor adjustment, reveals the idiopathic approach in full bloom as practiced 50 years ago. After an interview, TAT and Draw-a-Person test were completed, Jane was summarized (in part) as follows. “The child seems to rely on denial, repression, and projection as psychological defenses. Impulses were carefully controlled and the child placed an extremely high premium on being obedient and ‘good;’ however, at a deeper level, she had a considerable amount of hostility which was carefully contained behind repressive defenses…besides her obvious withdrawal, inhibition, and physical problems, Jane was handicapped in other ways. For instance, she was unable to utilize her intellectual resources to perform acceptable academic pursuits…Her limited experience also contributed to these deficiencies. Feelings of inadequacy caused her to anticipate failure in most of the task she undertook; therefore, she could not respond to school work with confidence.” (Blackham, 1967, p. 160). This is all about Jane uniquely (i.e., it is idiopathic). The narrative is devoid of nomothetic hallmarks. There are no standardized scores to quantify or categorize Jane’s problems. Rather, the report is about one girl singularly, as seen through the lens of Dr. Blackham’s clinical wisdom.

Talk about the defense mechanisms of denial and repression strikes many 21st century school psychologists as arcane and archaic (and perhaps objectionable). But one can still find contemporary proponents psychodynamic explanations for aberrant behavior. For example, Luyten and colleagues (2015) outline assumptions concerning modern psychodynamic theory—a developmental perspective, unconscious motivation, transference, a person-oriented perspective, complexity of each person’s own developmental lines, focus on the inner world, continuity between normal and atypical development. This begs the question of whether today’s school psychologists really need to know the deep background behind projective techniques? Must they become artful and insightful at projective interpretations? The answer is, it depends. It depends on where you practice and where your sequence of training takes you. In fact, projective techniques do remain popular in some school districts, even in states where few other school districts employ projective techniques. What’s more, there are some states where psychodynamic (Freudian) formulations continue to be in style. Some lead school psychologists, some teachers, and some parents may expect (demand) that you use projective techniques. This implies that projective technique use may at some point become an unanticipated aspect of your practice.

For doctoral school psychologists, experience with projective techniques might actually be required. This pertains to competitive training sites listed by the American Professional Internship Consortium (APPIC). Doctoral-level school psychologists applying to APPIC programs compete with students coming from clinical and counseling psychology programs. This is consequential because knowledge of (or at least appreciation for) projective techniques may represent an entry ticket to some APPIC training sites. There is high endorsement (72%), for example, among APPIC programs for broad training in assessment, with 35% of the programs themselves offering training in “story techniques” (Stedman, Essery & McGeary, 2018). In another survey of APPIC directors, 28% offered TAT training (Ready, Santorelli, Lundquist & Romano, 2016). This seems to match word-of-mouth reports of students making applications to APPIC programs, some of whom are shocked when required to describe their training in use of the Rorschach, TAT, and sentence completion techniques (including the number of first-hand cases in which each was used). Consequently, if you envision your training ever landing you at an APPIC site, you may choose to learn more about projective techniques during graduate school. This chapter represents a start.

Before diving into projective techniques, however, there is one easily overlooked role that needs to be mentioned. It’s school psychologists in the position of consumer, not just producer, of psychological test results. Let’s assume for the sake of argument that you are no champion of projective techniques. In fact, you never use them yourself and you are content to know nothing about them. One day, however, a parent drops off a packet of information concerning her daughter. She asks you to review the contents and then to discuss them with her regarding possible services. You guessed it, the packet contains a clinic-based report replete with projective techniques. Even if you disdain projective techniques, you have an obligation to this student to make sense out of what has been already done, to meet with her parent, and chart a course of action. Ignorance of projective techniques will prove to be a barrier to these things. Everyone needs to know the basics of projective techniques. Let’s look at some of the popular examples to get started.

Story Techniques

A number of techniques require students to make up a story while they examine a series of cards containing pictures. The images may be consist of drawings, photos or artwork. Administration and stimulus material are typically standardized.

Thematic Apperception Test

Perhaps the most representative projective technique is the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT, Murray, 1943). It is the classic “story technique.” Respondents are provided a series of pictures and asked to compose a story about each. The TAT’s author, Henry Murray, had previously developed a theory of personality centered around two concepts: “needs” and “presses.” A list of human needs (e.g., affiliation, nurturance, dominance, autonomy, blame avoidance) were catalogued in this theory, as were presses. Presses were envisioned as environmental influences that provoke and alter expression of needs, culminating in overt behavior. Thus, person-to-person differences in the array and intensity of needs (which are unconscious) coupled with changing environmental presses were hypothesized to determine personality. The TAT was created, in part, to assess needs and presses.

However, psychodynamically-oriented (Freudian) practitioners soon recognized practical uses. The TAT was envisioned as a tool for plumbing the depths of personality of individuals currently undergoing, or poised to undergo, psychotherapy. Murray (1951) himself commented on this applied TAT use, “The psychiatrist—particularly the psychoanalytically trained psychiatrist—should learn the art of administering and interpreting the TAT. The use of this instrument is recommended at the start, in the middle and at the end course of therapy, first of all as an aid in identifying suppressed and repressed dispositions and conflicts and in defining the nature of the patient’s resistance to these dispositions…..” (Murray, 1951, p. 577. Things that are suppressed or repressed are not subject to conscious awareness. The TAT, however, was envisioned to reveal them even when the respondents does not know they were doing so. As an aside, if there is any doubt that the TAT was created with an idiopathic focus, notice that clinicians should learn the “art” of interpretation. As another aside, Murray’s comments reach back to the distant past when psychiatrists were primarily psychotherapists, not psychopharmacologists.

What about today and use of the TAT with children in schools? To use tools like the Behavior Assessment System for Children-3 or the Autism Spectrum Rating Scale, school psychologists need to read the not insubstantial manuals and (perhaps) receive hands-on supervision for at least a few cases. But there is no reasonable TAT manual (just a flimsy, 23-page, stapled set of sheets that appears unchanged from the one prepared at the Harvard Psychological Clinic way back in 1943). More importantly, the process of TAT interpretation (as well as for other storytelling techniques) is drastically more nuanced and more slowly mastered than the process of learning to use rating scales. This means that it is necessary to turn to classic sources, such as a system devised by Leo Bellak many years ago (the latest version is Bellak & Abrams, 1997). More is seen about the Bellak approach later in this chapter. Alternatively, practitioners might rely on texts more directly suited to school psychologists, such as Teglasi (2001). Teglasi’s work, for example, covers TAT administration as well as guidance about using the TAT to size up a student’s cognition, emotions, object relations, motivation and self-regulation. Her work also includes illustrative cases. If you wish to master use of the TAT, you will need to read one or more of these sources. You will also need to find a mentor or enroll in a projectives-specific graduate course.

Although by history and organization the TAT is idiopathic, in the hands of researchers and practitioners the TAT sometimes becomes associated with nomothetic notions and quantitative research methods. For example, David McClelland at Harvard University launched at vast research program in which TAT responses of college students represented his raw data (McClelland, 1961; 1985). His concerns were individual-to-individual (and society-to-society) differences in achievement motivation (i.e., need for achievement). Need for achievement was conceptualized as a true need (not a mere response to social pressure or an ephemeral strategy for secondary gains [money, prestige]). Rather, this was the drive toward achievement to satisfy an internal need for personal accomplishment. It turned out that not only were measurable differences present on this dimension, but these differences mattered in many spheres of school and scholarly life. This was empirical, quantitative, research that was unconcerned with the uniqueness of individuals. Instead, this research sought patterns present in some individuals and absent in others depending on research variables. In other words, not every psychologist was willing to leave the TAT in the realm of creative (and one-of-a-kind) insights.

The same is true regarding children with clinical designations. For example, TAT elements (objectively determined) have been found to distinguish a group of students with emotional disturbance from a group of control students (McGrew & Teglasi, 1990). In this study, boys with ED struggled to complete TAT stories (i.e., these boys’ stories failed to meet fixed criteria for completeness and logical consistency). Specifically, boys with ED failed to incorporate elements of “feeling” into their stories, as they had been told to do. Relevant to practice, however, there was no cross-validation and the researchers’ purpose was not to apply this methodology to ED identification per se. However, storytelling may entail aspects of personality not tapped by self-report and informant rating scales, as this research implies. Other studies using clinical designations and more homogenous groups reflect the same notion of nomothetic research applied to TAT results. For example, Wodrich and Thull (1997) used the TAT for group-level research in an attempt to locate differences between children with and without Tourette syndrome. Attempts at donning nomothetic lenses to examine the TAT’s validity with children, however, are rare. The TAT is almost always considered as a way to get to idiographic considerations.

So, what about frontline clinical use and the TAT—how does this work? Exactly how might sense be made of children’s responses? There are 30 TAT cards, some specific to men/boys and others specific to women/girls. Because only 10 cards are typically used, a selection process is needed. Most diagnosticians have a pre-determined set of cards for pre-teen boys, another for pre-teen girls with slight variations to these sets for adolescent males and females. That said, there really is no fixed set of cards; cards selected for use vary from practitioner to practitioner. Here are typical directions, which are often modified to suit the understanding and developmental level of children.

“I am going to show you some pictures, and I would like you to tell me a story for each one. In your story, please tell: What is happening in the picture? What happened before? What are people thinking and how are they feeling? How does it turn out in the end? So, I’d like you to tell a whole story with a beginning, middle, and ending. You can make up any story you want about the picture. Do you understand? I’ll write down your story. Here’s the first card.” (Murray, 1943, p. 2).

The diagnosticians record responses (pencil and paper or via audio recording [for later transcription]) card-by-card. They prompt when needed. After all cards are completed, interpretation commences. There is no set procedure. In fact, with no fixed set of stimulus material and no fixed interpretation process some say that use of the term “test” is misleading. “The TAT should never be called the Thematic Apperception Test [underline added] unless a quantified scoring system is used and appropriate normative data are publicly available. The contemporary TAT is more akin to a highly specialized projective interview technique than a psychometric test.” (Rossini & Moretti, 1997, p. 395). To these writers, test means something nomothetic and the TAT isn’t generally used in a nomothetic manner. At any rate, some diagnosticians scan responses and draw conclusions immediately after having done so. Other diagnosticians make margin notes as they search for recurring themes among the stories, or they flag for later review especially noteworthy singular phrases or sentences. Many, however, follow a semi-structured approach. They examine each card and attempt to characterize what is revealed according to several dimensions. They may do so meticulously working step-by-step and card-by-card. The Bellak approach (Bellak & Abrams, 1997), with its dimensions listed below, exemplifies a detailed, card-by-card analysis process.

- Main theme of story. A thumbnail sketch of each narrative.

- Main hero of story. His/her gender, age, job, interests, self-image.

- Main needs. The hero’s drives, impulses and wishes.

- Conception of the world.

- Figures seen as…Environmental stressors, basic trauma that influences world view.

- Conflicts. As expressed by the story’s hero.

- Nature of anxieties. As expressed by the story’s hero.

- Main defenses. How the hero uses ego defenses regarding his/her anxieties, fears or conflicts.

- Super-ego functioning. Delay gratification of impulses, how appropriate (lenient, severe) superego functions as appear in story.

- Integration of the ego. Includes the following ego functions: (a.) reality testing, (b.) judgment, (c.) sense of reality, (d.) regulation and control (e.) object relations, (f.) thought processes, (g.) adaptive regression in the service of the ego [ARISE], (h.) defense functioning, (i.) stimulus barrier, (j.) autonomous ego functioning, (k.) synthetic-integration functioning, and (l.) mastery-competence.

All of these dimensions are evaluated relative to each TAT card presented. Even novice TAT users recognize that the cards are not neutral, and one card does not function like another. Most cards depict a social situation. As such, those situations encourage an array of stories, but not an infinite array. Rather, each card tends to “pull” the respondent toward certain concerns. It is what each respondent does with these pulls that matters.

TAT Card 2, which your instructor can show you or which you can find online, reveals the phenomenon of pull. https://www.psychestudy.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/TAT-2_0.jpg. This card tends to pull for stories about school, with the girl in the foreground commonly the hero (this is true whether a boy or a girl makes up the story). Stories for Card 2 often concern teens’ emancipation from family, family values vs. one’s own emergent values, and perceptions of schooling (the girl carrying a book in the foreground is often seen to be on her way to school). Table 16.1 contains stories provided by four adolescent girls when they had been presented TAT Card 2. Table 16.2 provides a glimpse into TAT analysis, which consists of a diagnostician’s notes on just four of Bellak and Abram’s (1997) dimensions of analysis. Note in Table 16.2 that the hero of each story is the same, and that schooling is commonly referenced, but that vast differences otherwise appear in the four girls’ stories. To aid interpretation, popular sources (e.g., Teglasi, 2001; Groth-Marnat, 2003) offer guidance about the features of the card as a foundation for interpretation.

Consider the amount of time, effort and skill required to complete an entire worksheet on a single student, such as Anna. If she completed the standard 10 cards and each card is analyzed on 10 dimensions, then 100 cells need to be completed to kick-off interpretation. Then the cells are examined for patterns and consistencies as a prelude to preparing a written summary. These time requirements are on top of those needed to conduct the sit-down TAT administration with the student. These considerations, coupled with those about the TAT’s compatibility with school psychology’s largely nomothetic and behavioral worldview, would seem to help explain the limited popularity that this projective technique now experiences.

Table 16.1 Students’ Responses to TAT card #2 |

|

1. Adolescent girl-Anna: This is a story about a girl going to school. She has her books under her arm. Before this scene, she got up early. She wanted to make sure she had all of her school supplies. She stayed up late the night before practicing for a test and she got up early this morning to practice again. Her family is a farm family, but she does not want this lifestyle at all. Instead of this, she wants to move to a city and grow up to be a doctor or a lawyer. Her mother is in favor of this, but her father wishes that she would stay on the farm. Right now, she’s feeling a mixture of excitement to get to school and worry that she might not ace the test. There may be a tiny bit of guilt for leaving her family to do all the work while she is away at school. But she is feeling that the test is important and doing well on it matters to her a really lot. The outcome of the story is that she earns the highest score in class. Her anxiety gives way to a feeling of satisfaction. In the future, she will get committed to hard work and from that hard work will come success. 2. Adolescent girl-Bethany: It’s another school day. You can tell from the look on her face that she is not that excited about it. She will go and she will enjoy her friends but that’s really about it. The dad looks pretty busy and the mother is taking a break after working a bunch already. She is pregnant and she already has a whole bunch of kids to watch out for. The dad has the older boys working on the farm. That helps him out. The girl has a load of chores too. She has probably already done some this morning. She will do even more after school. [Examiner asks: How does she feel?]. A little mixed up. She wonders why she has to learn all this stuff in school that don’t really help her in her daily life. She has heard her parents say that school for a lot of kids doesn’t matter that much. [Examiner asks: What does she think?] She more or less agrees. What is the reasons exactly? That kind of thinking. [Examiner asks: What happens in the future?] She finishes the school year but doesn’t go back for her last year of high school. She becomes happier to be going on with her life. She gets married and has a family of her own that live happily on a farm close by her own parents. 3. Adolescent girl-Carlita: This is a really old picture. Is this out of a movie? It’s a farm with a farm family. There is a horse in fields that have already been plowed. [Examiner asks: Can you tell me a story?] Well, this girl has a very worried look on her face. I think she may have a sick feeling in the pit of her stomach as she thinks about going to school. I noticed that her mother to the side looks relaxed and comfortable. I think next the girl will turn and look at her mother and notice her mother’s relaxed expression. The look of her mom will make her even more bummed about school than she already was to start with. Even though she knows she can’t do it, I think she would like to just stay home. Not go to school today. Maybe something like homeschooling. [Examiner asks: Why do you think she would like that?] If it’s just a story then I would go ahead and say she’s scared about being bullied or nervous about getting teased. She’s never had much self-confidence. Now that she’s older she feels even more that same like pretty negative way. 4. Adolescent girl-Danielle. This picture seems to contain a lot of disagreement. The dad is the one with the temper of course. He’s been up since early this morning plowing the field and working hard. He’s the kind of guy who would like to turn his farm into a big giant success. Maybe buy up two or three other farms. His wife is to the right. She does not really think this way. She would take it a little more easy. You can see that she’s leaning against a tree relaxing and not really doing any work. You cannot see his face, but I think he probably is either angry or frustrated. That would be the look on this face if you could get to an angle to see. The daughter is a little bit in the middle. She loves her mother and is kind of like her. Sort of like her mom, deep down she’s a little bit afraid of her dad. She wants to go to school but she feels like there might be a lot of parent disagreement while she’s gone. She ends up going to school. She’s reluctant when she’s there though. She sometimes thinks about what’s happening at home and wonders whether there might be blow ups. [Examiner asks: Can you describe these blow ups?] Sometimes it’s an argument and once in a while it becomes physical. She becomes trapped at this point because she can’t really do anything to protect her mother. [Examiner asks: How does she adjust to this?] Probably not very well. She has trouble sleeping, sometimes she’s jittery. In certain ways she hopes her dad will go ahead and get other farms and spend so much time working there won’t be any time left over for conflict. This looks like it could be back in the Vietnam War era. Maybe another ending would be that her mom’s brother comes back from the war. He lives with them on the farm, but he is a skilled fighter and very macho. Not mean, but macho and strong and confident. In fact, he might even be the alpha male type guy. There’d be an advantage to that because the dad would behave himself a little bit better if there was a warrior in the home. He would have no choice. |

Table 16.2 Abbreviated Interpretation of Four Adolescents’ Response to a Single TAT Card (card #2) |

||||

| Sample of dimensions of interpretation§ | Anna | Bethany | Carlita | Danielle |

| Main theme | Aspiring student aces test prior to leaving farm for better life | Disinterested student leaves school early to support parents in their hard life as she starts her own | Bullied girl fantasizes about homeschooling | Home conflicts leave girl powerless and anxious, prompting rescue fantasy |

| Hero | Girl | Girl | Girl | Girl |

| Main needs | Achievement | Responsibility | Comfort, safety, acceptance | Protection, nurturance |

| Conception of the world | Rich with opportunities to achieve | Onerous and rife with obligations | Threatening; challenging to comfort and self-confidence | Striving, but punitive, father and mother with different values |

| §Modified from Bellak and Abrams (1997); see primary sources for many more dimensions | ||||

TAT Alternatives, TEMAS and the Roberts Apperception Test

There are many, many alternatives to the TAT, including cards just for children (Children’s Apperception Test-2nd edition, Bellak & Bellak, 1965), that comprise scenes with cartoon characters. This might circumvent a concern expressed by some potential users that the TAT cards look extremely dated (and some of their scenes are agrarian, ill-suited to today’s largely urban and suburban youth). In truth, even during much of their era of maximum popularity the TAT cards looked out-of-date, but they still seemed to work. New cards often seem to lack the subtle pull of the classic TAT cards. In fact, it is argued that the old-school TAT cards still pull respondents in the direction of certain topics while avoiding overly prescribing how those topics are managed (Wodrich, 1997).

Another concern of the TAT is less easily dismissed. The cards are mostly depictions of White individuals. This fact could easily subvert the intended purpose of the tool and undermine its validity. There may be better options. One proposed better option is a tool entitled “Tell-Me-A’Story” test (TEMAS; Constantino, 1987). The TEMAS offers two parallel sets of stimulus cards. One set comprises cards with mostly Hispanic-American and African-American characters set in urban environments. Another set has mostly European-American characters in urban environments. There are long (23 card) and short (9 card) administration options. Administration and interpretation parallel aspects of the TAT. But in contrast to the TAT (which itself exists without a credible manual), the TEMAS affords a structured scoring system and standard scores based on a normative sample. This starts to sound somewhat nomothetic. And, in fact, its psychometric properties have been investigated. In fact, the TEMAS tabulates responses according to many standard dimensions (see Table 16.3).

It is interesting that the TEMAS aims to tackle some of the culture-specific limitations inherent in many projective techniques (especially the cards found in tools like the TAT). Yet, conventional, off-the-shelf projective techniques received a surprising rate of endorsement by school psychologists conducting ED assessments of English Language Learners (Ochoa, Riccio, Jimenez, Garcia de Alba & Sines, 2004). This included use of children’s drawing and sentence completion techniques, with usage rates between 75% and 50% of those responding to a survey. Larger, more recent and more representative studies of school psychologist, however, confirms much less frequent use of the TAT, with only about 5% of school psychologists using it at all (Benson et al. 2019). The TEMAS is used so infrequently by school psychologists that it failed to appear among those listed by these researchers (Benson et al., 2019).

Table 16.3 Dimensions Covered by Formal Scoring of Two Alternative Storytelling Techniques |

|

|

Tell-Me-A-Story (TEMAS) |

Roberts Apperception Test-2 |

|

Cognitive Function

|

Theme Overview Scales |

|

|

|

Personality Function |

Available Resources |

|

|

|

Affective Function |

Problem Identification Scales |

|

|

|

Resolution Scales |

|

|

|

|

Emotional Scales |

|

|

|

|

Outcome Scales |

|

|

|

|

Unusual |

|

|

|

|

Atypical |

|

|

|

Table 16.4 Summary from a Psychological Report Using the TEMAS |

|

“….Roberto presented strengths in certain cognitive functions such as reaction time (average range), storytelling time, verbal fluency (above average range), and imagination (average range). He showed weaknesses in the recognition of psychological conflicts and in thematic perseveration from card to card. In the personality functions, he showed strength in the areas of interpersonal relations with peers; and relative strengths in the areas of interpersonal relations with parental figures and siblings, delay of gratification, control of aggressive impulses, coping with anxiety and depression, and reality testing. Roberto showed weaknesses in the areas of moral judgment and self-identity/body image. Emotional expression was restricted with an elevated score in ‘Sad.’ Emotional indicators fell within the low to adaptive level, indicating the need for individual and group psychotherapy in a clinical setting.“ |

| From: Costantino, G., & Malgady, R. G. (1996). “Development of TEMAS, A multicultural thematic apperception test: Psychometric properties and clinical utility”.

Multicultural Assessment in Counseling and Clinical Psychology.

|

Chances are that you will hear mention of another storytelling technique, the Roberts-2 (Roberts & Gruber, 2005), more often than the TEMAS (with nationwide use at around 8%; Benson et al., 2019). Interestingly, the Roberts-2 goes out of its way to disavow being a projective technique (i.e., the authors now say that it lacks an “apperceptive” nature). Indeed, the first version of this scale was entitled the Roberts Apperception Test; clearly “apperception” was dropped from the later version, presumably to distance the scale from the family of projective techniques. These protestations aside, the Roberts-2 does require responses to cards and the process presumably involves projection of an individual’s own personality and needs into the cards. What is being claimed might actually be affinity for a nomothetic (not an idiographic) style of interpretation. Like with the TEMAS, there are standardize cards and standardized administration procedures. Table 16.4 reveals the extensiveness of Roberts-2 interpretation. Also, like the TEMAS, the Roberts-2 affords users norms. Once again like the TEMAS, the Roberts-2 offers three sets of cards: Caucasian, African-American, and Hispanic. Critically for practicing school psychologists, however, the Roberts-2 fails to lend itself to casual or infrequent use. For example, its test manual has three chapters requiring study: Chapter 3 (Scoring Instructions), Chapter 4 (Review of Test Pictures), and Chapter 5 (Interpretation). This would prove to be a lot to read (and remember) for only an occasional use.

The link below hints at the appearance of the Roberts-2 cards.

https://www.mindresources.com/media/com_eshop/products/resized/053855-max-500×500.jpg

Inkblots-the Rorschach Test

The Rorschach is a set of 10 standard inkblots developed in Switzerland and published in 1921. Figure 16.1 presents a Rorschach facsimile. The Rorschach has been in continuous clinical use for almost 100 years, often relying on some of psychiatrist Hermann Rorschach’s original notions. There is no manual accompanying the cards. School psychologists wishing to acquire Rorschach competence need specialized training, and this training is necessarily extensive and time-consuming. In the heyday of Rorschach use, many graduate training programs offered semester-long courses exclusively concerning the Rorschach. The typical approach was to learn one of five separate scoring systems, each named after its author (Beck, Klopfer, Hertz, Piotrowski, and Rapaport). A single test associated with five diverse scoring systems is a poor way to do things. Consequently, in 1974, John Exner published a “Comprehensive System” that effectively supplanted the prior five Rorschach systems and afforded a degree of order. Exner provided a detailed system, including administration, scoring, norms, and analysis of example cases. Exner’s material is vast and mastering it constitutes a major training commitment. For example, there are three volumes: Basic Foundations and Principles of Interpretation; Advanced Interpretation, Assessment of Children and Adolescents. In their latest editions (Exner 2002, Exner & Erdberg, 2005; Exner & Weiner, 1994; respectively) they comprise 1,687 pages, rendering them (and perhaps the entire notion of Rorschach use) suited only to the most intrepid practitioners who foresees the Rorschach as center to their practice for years to come. Perhaps favorably, there are software programs that assist in interpretation. For example, the “Rorschach Interpretation Assistance Program”-5th version) is available from the publisher Psychological Assessment Resource. Exner is one of the authors of this software. https://www.parinc.com/Products/Pkey/376

The Rorschach can be used for children as young as five years. Administration of the 10 cards commences with verbatim recording of responses (one or more per card) in the initial “Free Association” stage. Once all responses are recorded, the Inquiry stage starts. In this stage each response is revisited to determine which part of the inkblot was being identified during Free Association and, critically, what prompted that response (e.g., shape, color, shading, etc.). After the child is dismissed, a Coding stage ensues. Coding involves evaluation of each response individually, with results for each item entered on a “Sequence of Scores” sheet (or into a software program). There are seven dimensions for coding each response.

- Location and Development (area or part of inkblot identified)

- Determinants (source of response, such as form, shading, color of inkblot)

- Form Quality (quality of response to that portion of inkblot used)

- Contents (name or class of object, such as animal or portion of a human)

- Popular Responses (concerns whether the response was a frequently used one)

- Organizational Activity (level of organization needed to integrate the form used)

- Special Scores (presence of unusual aspects of the response)

There are not just these seven dimensions available for coding and interpretation, however. Rather there are sub-elements within each dimension and ratios among them. This all becomes quite complex and at least mildly exotic. Witness two cases reported in the literature, both of which rely on Exner’s Comprehensive System. One case is a 15-year-old girl named Karen (Murray, 1994). She was seen for depressive symptoms and regressive behavior. Karen was an A student and president of her class. She completed the Rorschach twice, with an extended interval of psychotherapy separating the two administrations. A small portion of Murray’s analysis of Karen’s Rorschach responses indicates the involvedness of the process as well as the nature of inferences possible.

“The first item in this category is the Ambitent measure, and there is no problem here because she has developed a sophisticated and consistent coping style that is heavily weighted to the ideation side. Although the EB ratio of 12:1 in the second testing raises some concern about the affective constriction and possible defensive inflexibility, a close examination of both protocols reveals considerable emotional richness.”

“The second measure, Zd, is also not positive, indicating that she is not inattentive to her internal and external world. In fact, her positive HV1 in the first testing and her second testing Zd of +7.0 suggests that she is somewhat hyperattuned to the world. In addition, Measure 3, Lambda, is also not positive: She is clearly not a simplistic and concretely self-focused individual.” (Murray, 1993, p. 47). Obviously, Murray is seeking to uncover aspects of Karen’s personality that might illuminate the psychological processes behind her depressive symptoms and regressive behavior. Consider the use of esoteric vocabulary found in this description and then recall the imperative for written communication to inform all readers (see Chapter 14 in this book). The summary above is likely a comprehension headache for anyone not versed in Rorschach coding details and associated inference making. The abbreviations make little intuitive sense; how any of these score variables translates to personality or social-emotional characteristics is a mystery to the naïve reader. It’s true that this case appeared in a journal concerned exclusively with personality assessment whose readership is likely entirely familiar with the Rorschach. But the use of jargon, both regarding the Rorschach itself and psychoanalytic theory, is striking.

Let’s look at another illustrative case in the published literature. It involves a student named DM, who was administered the Rorschach on three occasions between age 11 and 15 years (Viglione, 1990). His history included an absent father as well as a mother with repeated suicidal attempts and recurrent hospitalizations. Sadly, DM was placed in a shelter where he appeared withdrawn and where he was repeatedly confronted by an aggressive peer. Evidently, straightforward interviewing techniques found DM unwilling or unable to talk about his situation. The referral question concerned the presence of a severe disturbance versus a reaction to trauma. The first two Rorschach administrations suggested significant psychopathology, including depressive symptoms and possible episodes of psychotic thinking. Interestingly, DM’s third administration was associated with more positive results. The following is a small portion of an analysis of DM’s Rorschach responses from the third administration (referred to as DM3 in the passage). “Form quality and special scores are greatly improved. The use of unusual detail (Dd) in the record, the attention to shading detail and the attempts at precision in the use of forms reveals that DM3 developed obsessive mechanisms to control, to defend himself, and to cope. Furthermore, I propose an alternative interpretation of the extreme elevation in reflections (r = 3) by suggesting that, in an adaptive fashion, DSM3 may now be self-absorbed and may supply self-soothing and parenting functions for himself. This interpretation of r differs with the typical Comprehensive System understanding of reflections as representing grandiosity or rationalization and places it in a reactive and resilient perspective…” (Viglione, 1990, p. 292).

Once again for most readers, this all sounds quite foreign. It is interesting and instructive, however, that Viglione did not examine DM’s Rorschach in isolation. Because it had become apparent that DM’s emotional status was improved, the hypothesis of adequate adjustment was considered from more than a single perspective. In fact, DM’s parents completed a rating scale (Child Behavior Checklist; CBLC), as was a self-report measure (ASEBA Youth Self-report). These were blended with facts about DM’s current functioning to reach conclusions. Thus, Viglione employed an HR-like approach. That said, the Rorschach was envisioned as adding important insights to help support or refute two competing hypotheses (i.e., severe psychopathology vs. [less severe] reaction to trauma).

Advantages of Exner’s Comprehensive System over its predecessors notwithstanding, major Rorschach shortcomings remained. Some of these were seemingly redressed in 2011 with the appearance of a simplified system entitled Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS; Meyer, Viglione, Mihura, Erard & Erdberg; 2011). Later, Joni Mihura and Gregory Meyer (2018) provided extensive information concerning the rationale and advantages of R-PAS over Exner’s Comprehensive System. Among potential pluses are said to be: better management of individual scores (variables), better norms, less variable number of responses, reduced examiner differences, more efficient and credible interpretation, and use of nongender international norms. One Achilles heel of the earlier Comprehensive System was the risk of over-pathologizing examinees. Research suggests that R-PAS reduces this unwanted prospect regarding: (a) thinking and perception, (b) the reserve of psychological, cognitive, and emotional abilities, and (c) conception of human relationships (Viglione & Giromini, 2016). What’s more, the developers of the R-PAS have created a wide-reaching website. For example, FAQ on “Understanding the Results of Output for Child and Adolescent Cases” is transparent and easy to follow. The site also houses a R-PAS library with a compilation of published articles in pdf form plus a search tool. Everything is available here: http://www.r-pas.org.

Although relatively simplified, R-PAS is still daunting. For instance, the R-PAS system involves 60 variables that summarize responses across cards. These, in turn, contribute to interpretation. Here is a sampling (of just three of those 60 variables):

- R: refers to Number of Responses. It is said to reflect both ability and personal motivation.

- FQ-%: refers to FQ minus Percent (percentage of all responses that are distorted). It is said to reflect mistaken perception, misinterpretation, and predisposition to odd behavior or poor adaptation.

- C: refers to color determining a response to the card when there is no mention of form. It is said to reflect cognitive passivity or even helplessness related to some experiences.

The other 57 variables have similar concise explanations that can be found in Mihura and Meyer’s (2018) text on Rorschach use. As can be imagined, R-PAS interpretation remains a complex process, requiring study and focused skill development. Still the R-PAS is probably a better bet for interested school psychologists than the Comprehensive System. At Duquesne University, where the school psychology training program teaches hands-on Rorschach skills, the R-PAS system, not Exner’s Comprehensive System, is used (personal communication, Ara Schmitt, November 26, 2018).

Readers may discern elements of both nomothetic and idiographic perspective in Rorschach use, setting it apart from most of the other projective techniques. And there are school psychology Rorschach proponents. For some of them, the Rorschach’s appeal is heightened if the test is not link too closely with psychodynamic (Freudian) interpretations (Hughes, Gacono & Owen, 2007). “Within a multimethod strategy, personality assessment in general (Gacono & Hughes, 2004), and the Rorschach in particular, provide important data for a thorough understanding of the child. The use of Rorschach data can clearly serve school psychologists effectively in their attempts to help children to become successful in school” (Hughes, Gacono & Owen, 2007, p. 288). That said, research indicates that fewer than 2% of school psychologists ever actually use the Rorshach (Benson et al., 2019).

The Rorschach certainly is sometimes used with children in clinical settings. Here, its proponents might deploy it to address questions about the presence or absent of psychopathology, to judge the presence of psychological resources available in psychotherapy, or to respond to forensic questions. But how might it be actually used in schools? Among the many potential referral questions found in Chapter 3 (Table 3.1), some conceivably fit the Rorschach, whereas others probably do not. For example, referral questions like #4 (personality characteristics) or question #5 (planning for counseling) might fit. But, questions about special education eligibility (#10 – 13) generally would not. One exception to this generalization, however, might even exist. Disturbed thinking, that may denote schizophrenia, can be hard to detect. Critically, however, schizophrenia is one “characteristic” of IDEA’s emotional disturbance definition (see Chapter 10). The Rorschach is touted as possessing sensitivity to psychotic thinking, and Rorschach supporters cite empirical studies documenting this assertion (Mihura & Meyer, 2018). Thus, the Rorschach might arguably help detect schizophrenia in a way not possible for other techniques. As you have already learned, assessment strategies need to match referral questions as well as emergent hypotheses.

Sentence Completion Techniques

Perhaps the most transparent projective tool involves the simple process of presenting a set of incomplete sentences. There are many available versions of the sentence completion technique. For example, Holaday, Smith and Sherry (2000) listed 15, although most lack commercial availability. All of these involve partially completed sentences (called “stems”), each stem being followed by a blank space where respondents write their conclusion. A generic version of sentence completion is provided in Figure 16.2. Students with sufficient literacy (and motivation) jot down their endings for themselves, perhaps while the school psychologists occupies themselves scoring other test instruments and completing unrelated paperwork. For some students, however, the reading and writing reverts to the school psychologist. Under these circumstances, the school psychologist would read the stems aloud and write the student’s words down on paper. Although research suggests that this assistance is typically unnecessary for students in the sixth grade and above (McCammon, 1981), the practice nonetheless appears to be widespread based on surveys of practitioners (Holaday, Smith & Sherry, 2000).

Some sentence completion techniques possess firmer methodological foundations than others. For example, the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank has roots extending back to the 1950s. Commercially available, this tool has remained one of the most popular sentence completion techniques over many decades, including with school psychologists (Hojnoski, Morrison, Brown & Matthews, 2006). From its outset, the Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank was the subject of research concerning interrater reliability, internal consistency, dimensional clustering of items. Also studied were convergent validity regarding socio-metric ratings, teacher interviews, and child interviews (Rotter, Rafferty & Lotsof, 1953). Rotter and colleagues, in their high school version, also took pains to indicate what the scale’s 40 items tapped, which looks like an effort to insure full construct representation. For example, items address the following three categories:

- Social (relationship to other students, activities, leadership ability, relationship to teachers)

- School (kind of student—grades; any difficulty with school activities)

- Family (relationship to siblings)

The empirical orientation of its authors is also evident by anchoring individual items via explicit examples of various teens’ responses (see Table 16.5). As evident in this table, responses to a particular stem (this one concerning father) can be rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from high conflict filled, through neutral, to high positive. Although the manual for the current version of this instrument (Rotter Incomplete Sentence Blank, second edition; Rotter, Lah & Rafferty, 1992), provides a method for generating scores, in the field this practice is probably routinely skipped. To this point, when Holaday, Smith and Sherry (2000) surveyed participants about following manual guidelines for scoring sentence completion techniques, a scant 7% said they actually used the practice. Most practitioners, obviously, use impressionistic techniques, such as jotting notes in the margin or using a highlighter to denote particularly noteworthy responses. Most users of the sentence completion technique are looking for insights into personality, not formal measurement of traits or dimensions of personality and certainly not diagnostic categorization (i.e., they are looking through idiographic lenses).

A skeptic may ask whether sentence completion techniques add anything over and above standard social-emotional tools. After all, isn’t the sentence completion technique just a minor variation of a clinical interview? In other words, if the stems provoke responses about school, friends, and family, wouldn’t an interview touching on these topics accomplish the same thing? In the same vain, how actually “projective” are incomplete sentence techniques? One might surmise that even uninsightful students have figured out that their incomplete responses are self-revealing. However, it has been argued that there is a subset of youngsters who are non-disclosing during a clinical interview only to open up when writing in an incomplete sentence booklet (Wodrich, 1997). For these individuals, the arm’s-length nature of the questions may prompt openness. After all, the questions do not involve direct inquiry about the individual but rather are general in nature (there are differences between answering the question ”How do you feel about your mother?” and completing a sentence that begins with “My mother…..”). Clinical interviews involve questions spoken aloud and answers said aloud. In contrast, sentence completion techniques can be completed in writing with nothing said aloud and with students’ answers left uninspected until they have returned to class. A sentence completion protocol may simply seem more comfortable for some students.

Because sentence completion techniques involve minimal time and effort, relatively little equipment, and are so appealingly straightforward, some school psychologists may choose to make them their idiographic add-on to an instrument-based objective assessment battery. This can be accomplished without need to shoulder the extensive training requirements incumbent in storytelling and inkblot techniques. For example, in Franklin’s case (Chapter 2) a sentence completion form might have been administered in lieu of interview or (more probably) as an interview warm up. Franklin’s school psychologist might have done so even if they rarely used the technique and lack in-depth training in it.

As is the case with projective techniques generally, use of sentence completion strategies has waned since at least 2003 (Piotrowski, 2018). Nonetheless, the sentence completion technique is still in use by up to one-quarter of school psychologists, making it the most popular projective technique used on campuses (Benson et al., 2019). That said, Piotrwoski’s survey findings suggest that psychologists who work with children, including school psychologists, continue to value the technique more than their adult-oriented counterparts. Furthermore, the same survey suggests that internship programs continue to value the technique.

Table 16.5 Anchors for a Sentence Completion Item Concerning Father |

|

| Stem: My father….. | |

| Conflict3 | I don’t care too much about him; is a person I don’t like too well; is very harsh |

| Conflict2 | is a very sick man; spanks me; is very strict |

| Conflict1 | isn’t very well; gives me what I want; is nice to me |

| Neutral | is dead; works hard; is letting me use the car occasionally |

| Positive1 | is good; is a great man; helps me with my homework when I need help |

| Positive2 | is a fine man; is a wonderful man; and I get along very well |

| Positive3 | is a great guy; is the best; is one the best |

| Abbreviated from Rotter, Rafferty and Lotsof (1953). | |

Projective Drawings

Projective drawings comprise a mixed group of assessment procedures, although they share some features. Specifically, all require the child to execute a drawing, usually on a blank (8.5 x 11 inch) sheet of white paper. In general, projective techniques are quickly executed with minimal equipment, and all are suited to children who may be unable (or unwilling) to talk about their lives. What’s more, all presumably rely on the projective hypothesis–drawings reflect the child’s internal states and personal perceptions.

Draw-A-Person

This is the simplest, and probably most popular, of the projective drawings. It might be used as one element of a multi-tool assessment battery. The child’s task is simply to draw an individual. The directions are intentionally left vague. (The reader should note that there is a parallel procedure that involves drawing an individual that is entitled “Draw-A-Man” or “Draw-A-Woman,” which is scored for developmental level, not social emotional status [see Harris, 1963]). Social-emotional interpretations of the Draw-A-Person date to at least 1949 when Karen Machover authored a volume entitled Personality Projection in the Drawing of Human Figure: A Method of Personality Investigation. Machover’s work relied on individual characteristics present in a child’s drawing, each of which was said to reflect the likelihood of a personality or emotional characteristic. For example, when a diminutive (small) human figure was drawn, the child may be revealing a regressed personality with depressive features. Machover’s original work was expanded by Elizabeth Koppitz whose 1968 volume listed 30 characteristics suggestive of maladjustment (see Table 16.6).

Table 16.6 Draw-A-Person: Koppitz’s emotional indicators and explanatory items |

|||

|

Quality signs |

Special features |

Omissions |

Explanatory items |

| Poor integration of parts | Tiny head | No eyes | Happy face |

| Shading of face | Crossed eyes | No nose | Sad face |

| Shading of body or limbs | Teeth | No mouth | Worried face |

| Shading of hands or neck | Short arms | No body | |

| Figure slant > 15 degrees | Long arms | No arms | |

| Tiny figure | Arms clinging to body | No legs | |

| Big figure | Big hands | No feet | |

| Transparencies | Hands cut off | No neck | |

| Legs pressed together | |||

| Genitals | |||

| 3 or more figures drawn | |||

| Clouds | |||

As you have already learned (i.e., Chapter 9 regarding interviewing), school psychologists must be especially circumspect when they think they may have detected possible physical or sexual abuse. Angelique LaRue is a first-year school psychologist. Well versed in standard observation procedures and behavioral rating scale, Angelique was never trained in projective techniques. Nonetheless, she noticed that school district colleagues often used the Draw-A-Person test as a supplement to their otherwise largely objective social-emotional test batteries. Angelique started to do the same. Her first several cases turned up nothing interesting—each student seemed to have created an unremarkable depiction of a child, although the level of detail and overall quality of execution clearly varied. The occasion of her fifth Draw-A-Person technique, however, was striking. An eight-year-old girl depicted a young female form with large eyes and enormous hands each of which covered the entire lower abdomen including an area that would have included genitals. This struck Angelique as frankly odd. She immediately thought that the rendering might convey a vigilant, perhaps traumatized, girl who was guarding herself against the prospect of sexual assault. She wondered, might this girl be revealing (perhaps unconsciously) a history of sexual abuse? Many readers would be thinking that Angelique needs to proceed cautiously. A logical step for Angelique would be to determine if there is any empirical evidence for interpretations like the one she is contemplating. Consider Allen and Tussey’s (2012) succinctly stated research question on this very topic (which is also the title of their article): “Can projective drawings detect if a child experienced sexual or physical abuse?” Their answer was “no.” To arrive at this conclusion, these researchers combed the published literature on projective drawings of children who had been sexually abused. Specifically, they looked for the presence of “graphic indicators” (e.g., drawings that included depictions of genitalia or that left out some body parts). The logic was that these indicators might distinguish children with a history of abuse from their non-abused counterparts. The empirical literature indeed failed to support this hypothesis. Although group differences were sometimes found on a few characteristics, the differences were judged to be dubious because of methodological weaknesses (e.g., isolated findings, no cross validation).

Regarding element-by-element analysis, other disappointing research findings abound. These include lack of evidence that various details indicate gender preference in boys (Bovan & Craig, 2002) or that Draw-A-Person characteristics denote depression in boys and girls (Gordon, Lefkowitz, & Tesiny, 1980). Even when some specific characteristics of children’s drawings differ between clinical and control samples the differences may not be large. Furthermore, these studies do not include clinical utility statistics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity). Just this was found, for example, when level of pencil pressure exerted while drawing was used to predict anxiety (LaRoque & Obzrut, 2006). There is a correlation between pencil pressure and some, not all, indicators of anxiety but there is no clear way to use this information in field-based practice.

Lack of support notwithstanding, clinicians, even those seasoned professionals who have received specific training in projective techniques, sometimes come up with misinterpretation of individual aspects of a Draw-A-Person protocol. Smith and Dumont (1995) cite three examples that illustrate misinterpretation. Listed below are verbatim comments spoken by clinicians as they explained their inferences about drawings they were judging:

- “The only thing to me that’s curious is how broad the shoulders are, which indicates that he feels he’s carrying a terrible and heavy load.”

- “Well it’s a rather big man with a lot of anxiety. Short hands that are stiffly held down, I would say an inadequate, anxiously depressed person with identity problems.”

- “There are indications for dependency, lots of buttons and buckles” (Smith & Dumont, 1995, p. 301).

Perhaps the standard Draw-A-Person interpretative approach, rather than the tool itself, is at fault. Some researchers have questioned the validity of individual characteristic-by-characteristic interpretation. To this end, Tharinger and Stark (1990) conducted a study using both item level (Koppitz system) and holistic approaches to predict youngsters’ internalizing psychopathology. They found that individual item analysis failed to discriminate among anxious youth, depressed youth, and controls, whereas holistic approaches did. Specifically, four general characteristics were judged by these researchers to help them reach a summary opinion about the “Psychological Functioning of the Individual.” The four general characteristics indicating problems were:

- Inhumaneness of the drawing (animalistic, grotesque, or monstrous; if humans were depicted, they might be missing essential body parts or appear disconnected)

- Lack of agency (a drawing that appears incapable of interacting with the world or seems powerless)

- Lack of well-being (negative facial expression, including anger, fear, or sadness)

- Hollow, vacant, or stilted depictions (figures perhaps depicted as frozen or unable to move)

Figure 16.3 includes a set of children’s Draw-A-Person responses. It’s potentially worthwhile to examine each of these figures by looking at Koppitz’s various item-level considerations (Table 16.6) and the contrasting holistic approach as outlined by Tharinger and Stark (1-4 immediately above).

There is one more consideration regarding the Draw-A-Person technique—this concerns screening. Screening is the idea behind a commercially available option entitled Draw-A-Person: Screening Procedure for Emotional Disturbance (Nagileri, McNeish & Bardos, 1991). This tool is designed for youth 6 to 17 years. Items are scored for three drawings: a man, a woman, and self. T-scores are available as are cut-scores concerning suggestions about further assessment (more detailed assessment is not indicated, indicated, strongly indicated). Unlike the other Draw-A-Person options, this one includes a quite large national normative sample. Follow-up research (Nagileri & Pfeiffer, 1992) found statistically significant differences between a control and a clinical sample, although effect sizes in this study were rather modest. No sensitivity or specificity data were reported.

Kinetic Family Drawings

Much like the Draw-A-Person test, the Kinetic Family Drawings involves depicting human forms. There is a published manual, which is quite dated (Burns & Kaufman, 1970). The difference between the Draw-A-Person test and the Kinetic Family Drawings, however, is that an entire family is depicted in the latter, with the request that each member is portrayed doing something. As one might speculate, this opens vast interpretive possibilities. Because many child clinicians work in outpatient settings where the entire family is involved in treatment and decision making, adding family content to drawings would seem to make sense. School-based practice is another matter. In schools, interactions with, and perceptions of, classmates or teachers, not parents or siblings, are likely to hold more importance. And, of course, questions about special education eligibility are unlikely to be informed by family dynamics, no matter their salience in children’s drawings. Still, there are interpretive manuals and supporting documents to facilitate the process. The study cited above by Tharinger and Stark (1990) offer support for holistic interpretation of the Kinetic Family Drawings.

House-Tree-Person Drawings

Here the child’s task is to depict a house, tree, and a person, which in turn is subject to interpretation. Once again, there is concern that claims of the technique’s value exceed supporting evidence. For example, one House-Tree-Person drawings manual is little more than a set of cases (Burns, 1987). Another dated manual (Wenck, 1970), apparently is an update of work from 1948 by an early proponent of the House-Tree-Person Drawings (Buck). Researchers too have offered organizational schemes for House-Tree-Person drawings. Concerning the house element, for example, several dimensions can be rated on a Likert scale (Groth-Marnat & Roberts, 1998):

- Essential details present

- Firm lines quality

- Groundedness of the house

- Moderate proximity of the house, tree and person

- Integration of the house, tree and person

- Accessibility of the house

- Openness and accessibility of the person

- Presence of homelike objects

- Healthiness of the tree

Yet another House-Tree-Person manual exists, but this one concerns a circumscribed purpose– detecting child abuse (Van Hutton, 1994). Recall from Angelique’s situation the risks incumbent in this consideration. As reflected in the manual, Van Hutton collected House-Tree-Person drawings (as well as Draw-A-Person) for 20 sexually abused children and compared them with drawings of 145 children collected from public schools and summer day camps. This permitted development of themes for examining drawings (see below) and cut-scores for her system.

Van Hutton’s process to produce scores in this system concerned the following:

- Preoccupation with sexually relevant concepts

- Aggression and hostility

- Withdrawal and guarded accessibility

- Alertness for danger, suspiciousness and lack of trust

All of this is logical, but the question is how well it works in practice. Just this topic was addressed by Palmer and colleagues (2000) who compared House-Tree-Person drawings of 47 children with a history of sexual abuse and 82 matched counterparts with a history free of abuse. When a sophisticated statistical procedure was used (discriminant analysis) group membership could not be determined. In fact, many House-Tree-Person drawing items suffered from poor inter-rater reliability when the standard, published Van Hutton (1994) system was used.

Why are you reading so much about drawing techniques? It’s because they are used by school psychologists. Roughly 16% of school psychologists reported using the Draw-A-Person technique; the same 16% was found regarding the House-Tree-Person technique (Benson et al., 2019). Even if you never use projective drawings, expect to see their appearance from time to time among the array of tools used by colleagues when you run across a report prepared by another school psychologist.

What Might the Future Hold for Projective Techniques?

As the nomothetic worldview has gained ascendency, the popularity of projective techniques has waned. It now seems that some projective techniques even disavow their idiographic roots. For example, consider the wording of authors of the R-PAS approach, “The Rorschach offers both nomothetic and idiographic techniques for evaluating test takers’ performance” (Meyer, Viglione, Mihura, Erard & Erdberg, 2011, p. 1). Rorschach proponents even debate which Rorschach system affords better norms! This is not a proper debate for citizens of an idiographic world. Similarly, the Roberts-2 no longer self-identifies as a projective technique. The Roberts-2 proposes that practitioners calculate raw scores, convert them to standard scores and follow formulaic interpretations. The nuanced internal life of the storyteller would seem to become lost in a host of numbers and standard scores. With changes like this occurring, what then will become of projective techniques? Maybe they will disappear. Or maybe elements inherent in their stimulus materials (indistinct blots of ink, blank pages beckoning a child to draw) will ultimately prove sufficiently persuasive that today’s projective tools will live in some form during the decades ahead.

Alternatively, perhaps projective techniques will only survive as norm-referenced, standardized tools intent on finding recurrent patterns rather than the uniqueness of each human’s experience. Perhaps they will remain part of the training of some school psychologists because of their potential to promote psychological mindedness (see Illustration 16.1). But of course, school psychologists possess no crystal ball capable of glimpsing the future. For now, it seems wise for school psychologists to become a bit familiar with this array of techniques, no matter what the future holds.

Illustration 16.1 Is it too far fetched to think that projectives may impart an unintended benefit of promoting psychological mindedness? A number of years ago, I (DLW) worked in a children’s hospital that was adding a child psychiatry fellowship program. Physicians who had already completed a general psychiatry residency program could apply for two additional years of training in child and adolescent psychiatry. The new program’s training director asked some of us psychologists to sit in on the interview process. Happily, he had prepared a multi-item checklist on which each applicant was to be rated by each interview-team member. Most of the items were straightforward. They involved quality of prior training, strength of letters of recommendation, ability to communicate clearly during their candidate interview, etc. But one item was less clear-cut. It was entitled “psychological mindedness.” When asked about this item, the training director was as clear as he was emphatic. His concern was that some otherwise-qualified applicants may fail as a child psychiatrist because of limited psychological mindedness. In other words, a child psychiatrist risks encountering limited success without the ability to recognize what children and parents are thinking, what factors are important in their lives, what current stresses are operating, and their motivation for change. Without the capability to pose and answer questions like these, the psychiatrist might over-rely on the mechanics of diagnostic interviews, blindly use the criteria found in DSM, and rotely prescribe medications. He wanted no such trainees.

Might not similar considerations exist for school psychologists? Psychological mindedness could prove valuable for understanding the perceptions, needs, conflicts, and aspirations of all stakeholders encountered in helping children? Learning to interpret projective techniques might promote just these kinds of considerations. Of course, they do so in a focused manner, considering only children undergoing assessment. Maybe school psychologists should familiarize themselves with common projective rubrics for general purposes, not just concerning students undergoing assessment. Accordingly, the particulars of these rubrics may sensitize them to the internal world of everyone that they encounter. In other words, training in projective techniques might help them become more psychologically minded school psychologists. Even if projective techniques offer nothing to nomothetic conceptualizations and prove too unreliable to provide much for idiographic considerations, it’s possible that they still help psychologists learn to think like psychologists. It’s possible. On the other hand, today’s training programs are already so packed with content as to seemingly leave no room for training in something so archaic as last century’s projective techniques.

Summary