4 Background Information

Key takeaways for this chapter…

- There are many potential sources of background information

- Some background information comes from existing school records, making school psychologists uniquely positioned to conduct thorough assessments

- Face-to-face interview(s) with teachers may help clarify existing school records and promote diagnostic insights

- Some background information comes from parents, often in pre-evaluation questionnaires

- Face-to-face (or phone) interviews often illuminates information contained in parents’ pre-evaluation questionnaires

- A second parent interview is sometimes needed to confirm one or more hypotheses

- Background information is indispensable in hypothesis formulation and verification, such as used in the HR approach

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- Brian Baxter, revelations derived from background information

- Martha Yazzie, practice within a familiar culture

- Savannah Smith, practice within an unfamiliar culture

After establishing the referral question, school psychologists typically turn to the topic of background information. Although locating and scrutinizing background information sometimes requires time and effort, the payoff can be substantial. You got a glimpse of this already when the HR approach was introduced in Chapter 2. The same is true in those instances when you might use a probability nomogram (as you progressively update the chances that a particular condition is present). Perhaps more importantly, background information is indispensable for completing checklists, such as those advised for many special education eligibility decisions. In this chapter, you will learn about the varied sources of background information. Depending on local circumstances, school psychologists’ preferences, and referral questions, any or all of the following might be tapped:

- Anecdotal information, comments left behind by prior teachers

- Background (and current) information from existing classroom teacher(s)

- Official cumulative educational records

- Record of special services (often kept in a separate confidential file)

- Review of parent-completed pre-evaluation questionnaire or “Social-Developmental History” forms

- Interview of parent(s) face-to-face or by telephone

- Review of reports prepared by out-of-school professionals

- Review of permanent work products

Anecdotes Left behind by Prior Teachers

All kinds of psychological tidbits can be discovered when school psychologists look over existing documents. For example, prior teachers, social workers, or administrators may have written about a specific event with emotional or behavioral implications. Alternatively, they sometimes write down their general concerns that prove germane at the time a student eventually comes to professional attention. Likewise, prior correspondence with a parent might occasionally be found. School psychologists learn to take information where they find it without too many preconceptions. Consider the note (Illustration 4.1) left by last year’s first-grade teacher concerning a current second-grade student named Brian Baxter.

Illustration 4.1 Note from Brian Baxter’s first grade teacher (Ms. Ross)

To whom it may concern (regarding Brian Baxter):

I have been Brian’s teacher throughout his entire first grade. He was a reluctant student right from the beginning of the year. It took a lot of cajoling to get him to participate in activities. He had a hard time transitioning. He appeared extremely shy and self-conscious all year long, although that got better as the year went along. Even though Brian scored satisfactorily on end-of-the-year reading and arithmetic testing, he did not meet standards regarding writing. Also, he did have trouble completing work. This was almost entirely when he was asked to write. He seemed embarrassed and couldn’t start.

As the year went along, I think Brian sensed that I was his friend and that he could confide in me. I discovered he’s a worrier. He asked me several times about what his mother was doing at that particular moment in time. He said that he had heard about car wrecks on the news and was worried that his mother might be in a wreck. When the wind blew too strongly, he said that he was worried that his school bus would turn over on the way home. I needed to reassure him several times that I would not make him give an oral report in front of classmates if he was too worried about doing so. He is such a cute, kind, and sweet boy that it concerns me he might be suffering. This was the reason I persuaded the Child Study Team to go forward with an evaluation. It seems like a behavior plan or counseling at school might really help him. I’m sorry that we’re so stretched for resources that only students with IEP’s can usually get this type of help.

I regret that I’m leaving Dancing Dolphins Elementary for my new job in Philadelphia. But I would be happy to talk about Brian with the evaluation team next fall if that would help (I’ll leave my cell phone number with the office staff). By the way, I shared my concerns with Brian’s parents. They’re on the same page—eager to do whatever to better understand and get their kid the best school experience possible.

Sincerely, Betsy Ross, May 22, 2021

Now is a good time to revisit what you learned about referral questions in Chapter 3. For starters, Ms. Ross’s absentee referral might be considered beside the list of potential referral concerns seen in Table 3.1. First consider if Ms. Ross’s referral question fits among any of the options 10-13 (those highlighted in blue). If so, which might be the best match? If options 10-13 provide no match, which of options 1-9 would work? In the context of your school, and given time constraints on psychological services, would Brian’s referral question actually get accepted?

Teacher Interview in Search of Background Information

It’s not surprising that Ms. Ross’s note prompted the school psychologist to gather additional information, assuming that she decides to go forward with Brian’s case. Before looking into his school folder, she talks with Brian’s current (2nd grade) teacher, Ms. Madison (see Illustration 4.2).

Illustration 4.2 Interview of Brian Baxter’s Second-grade Teacher (Ms. Madison)

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Thank you for taking a few minutes to discuss Brian’s situation with me.

TEACHER: No problem.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: This is a busy time of year for you, right?

TEACHER: Yes. Kind of like always.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Just to be clear. We have signed paperwork from parents to conduct a special education evaluation, if warranted. You should anticipate that what you tell me might show up in a report. Also, just to be clear, what I might tell you regarding information I collected on Brian needs to remain confidential.

TEACHER: Sounds good.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: In a general sense, are you concerned about Brian’s behavior or emotions?

TEACHER: Yes, I certainly am.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So, what is your main concern, actually?

TEACHER: Well, I’m concerned about how he feels. That’s for sure. But I’m also really worried about him falling behind because of his performance in class. It seems like for anything novel or unfamiliar he freezes. If you pay attention to him and try to encourage him, he seems to become even more embarrassed and even less likely to respond. That raises my concern for him as another human being. It breaks my heart.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I know, we all empathize when someone seems to be in distress. You mentioned falling behind, so, has he actually been falling behind academic expectations for a second grader?

TEACHER: That seems to be the case regarding written assignments. He doesn’t complete some of them so he’s missing out on some things like simple punctuation and capitalization. These are important because they are part of a foundation for later writing. I mean, I think he’s not learning these things, but I can’t really be sure because there are so few work products for me to use to verify.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: How often do you see this?

TEACHER: Pretty much daily, but it does vary based on the nature of what’s expected of him. I would say any time something is uncertain or if attention is called to him there’s a strong chance that he will simply not respond.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Is there any discernible pattern? In other words, is there a time of day or something based on other children being present, differences from one day of the week to another associated with this?

TEACHER: I don’t think so. Again, it seems to be fairly consistently tied with a chance of embarrassment.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So, you’re saying it seems like he’s frightened or uneasy, right?

TEACHER: Yes, absolutely.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Do you see any other signs that might suggest nervousness or anxiety?

TEACHER: I guess so, yes. He bites his nails, he sometimes seems preoccupied, and at times he taps his leg nervously.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Does Brian seem like a perfectionist?

TEACHER: No.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Are there particular things he’s afraid of?

TEACHER: What do you mean?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Examples might be heights, the dark, bugs, things like that.

TEACHER: Oh, I see. I would say he’s afraid of public speaking.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Is there much of a reaction?

TEACHER: Big time. Looks flushed and ready to faint if it’s anything formal at all. If he had his way, he would never speak up in class even with the informal stuff.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: How does he do with other children?

TEACHER: Not too bad in class but we don’t expect much in the way of interaction during class itself. My philosophy involves students working independently rather than in groups. But on the playground, he sometimes isolates himself and really only plays with one other boy.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGISTs: What does his mood seem like?

TEACHER: Well, he can be happy at times but at other times he seems preoccupied. He does have a sense of humor that comes through when he’s relaxed. He does not seem depressed to me, if that’s what you’re asking.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Back to academics, does it seem like he’s up to reasonable standards regarding reading and understanding plus computational arithmetic?

TEACHER: In general, I’d say yes, he is. But we have had sometimes where he’s been reluctant to read and his voice volume was sometimes quite low. I’ve seen this of other nervous or shy kids in the past. He can read fluently and he does understand what he reads at grade level. He seems most relaxed during arithmetic and he has memorized his facts and can get through worksheets pretty well.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’m going to guess that based on what you’re saying, he’s not really a management problem or behavior problem.

TEACHER: No [chuckling], not really unless you count refusing to write when he’s asked to as an example of a behavior problem. That’s not what I think of when I think of a behavior problem.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: What about preoccupations, strong interests, peculiarities?

TEACHER: No, I haven’t seen any of that.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Have you ever thought he was acting strangely? Such as poor reality contact, responding to internal hallucinations?

TEACHER: No, not at all.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Has he ever expressed strange ideas? These might be like belief that things that cannot really be true are true; in other words, delusions.

TEACHER: Certainly not.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Have you ever thought that you were close to issuing a discipline referral for Brian?

TEACHER: No.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Do you have concern about his attention and focus?

TEACHER: Do you mean like ADD?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes, not necessarily hyperactivity though.

TEACHER: No, not really. He is if anything hyper-focused. But he seems to scan the world for things that might be scary or worrisome. When he is relaxed, he certainly seems attentive enough for a second-grade boy.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: While we’re on the topic, any concern about hyperactive behavior, thinking without acting, motor restlessness.

TEACHER: No, that is not Brian.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Is there anything else that concerns you about Brian?

TEACHER: Early in the year he had a number of trips to the nurse’s office complaining of bellyache. I think this might’ve been avoiding things he didn’t want to do in class.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: What do you think that was about?

TEACHER: I don’t know. Maybe nerves. Maybe avoidance. Maybe he feels like the nurse creates a safe space. She is very kind and welcoming. I think that is good, but sometimes I wonder if too much kindness creates a counter-productive sanctuary. You know, feel a little queasy and you are out of class. I don’t know. Just thinking aloud. I’m sorry I need to get back to my classroom now. I would be happy to talk with you later in the day. Just let me know.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I appreciate your input, were going to try and figure out what’s going on with Brian. For now, it sounds like you do have concerns and that they center around his nervousness and potential falling behind in writing. So, how does 3:10 after the final bell work for you to chat further?

TEACHER: That would work. Back here [meaning in her classroom] to meet?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes. I’ll see you back here. Thanks much.

The interview seemed to unfold spontaneously and intuitively. You might notice, however, that the school psychologists started generally (“What is your main concern..?”). More pointed inquiries ensued after the teacher had confirmed that she indeed harbored concern about Brian. You might also notice that the school psychologist engaged wide ranging topics. Plus, some of her questions were idiographic in nature, some nomothetic. For example, there were many probes concerning mental health conditions (“Do you see any other signs that suggest nervousness or anxiety?”). But other questions focused on situational factors (“…is there a time of day or something based on other children being present…?”) or might concern factors specific to Brian and his life (“What do you think might be causing this?). At all stages in the unfolding assessment process it is wise to consider both nomothetic and idiographic hypotheses, as you learned when you were introduced to the HR Worksheet. Because teacher interviews typically occur early in the assessment process, however, fine-grained questions (e.g., attempts to operationalize behavior and nail down antecedent and consequences) generally do not occur here (unless the referral question concerns development of an FBA; see Table 3.1). You may notice that this school psychologist also exercises good interpersonal skills. She sensitively verifies Ms. Madison’s heartfelt regard for Brian, and she shows herself to be a good listener by faithfully following the teacher’s narrative thread (e.g., Ms. Madison mentions offhand that Brian is “falling behind” and the school psychologist soon seeks confirmation and elaboration on this very topic).

You might surmise that the interview of Ms. Madison was conducted by a seasoned school psychologist. But how might a less experienced practitioner proceed? Is there a general template available to be follow when information needs to be coaxed from teachers? The answer is, more or less, yes. Table 4.1 lists a few commonly covered topics. There are, of course, other outlines for teacher interviews (e.g., McConaughy, 2013; Shapiro, 2010). The idea, however, is to adopt an approach to teacher interviews that remains congruent with your assessment style, the immediate referral question, as well as each case’s presenting problem.

Table 4.1 Possible Teacher Social-Emotional (Brief) Interview Topics |

|

|

Topic |

Example |

| 1. Build rapport/engage in small talk | We’re back at it again. I wonder if this one will be like the student from last year. |

| 2. Explain purpose of interview | As you know, I’m here to follow up with your referral about Brian. |

| 3. Explain boundary of confidentiality | The usual rules of confidentiality apply.

Information shared with me might show up in print in my report. |

| 4. Make general inquiry about overall level of concern | Overall, is it true that you have concern about Brian’s behavior or emotions? |

| 4a. Ask for elaboration | Can you explain the nature of your concerns? |

| 5. Ask for a description of all behaviors of concern | Could you describe anything that concerns you about Brian? |

| 6. Make specific inquiry about relations with classmates | How does he get along with other students? |

| 6a. Ask for elaboration if #6 is remarkable | How big of a problem does this seem like?

Why do you think this problem exists? |

| 7. Make specific inquiry about relations with teachers and staff | How does he get along with you [and your aide]? |

| 7a. Ask for elaboration if #7 is remarkable | How big of a problem does this seem like?

Why do you think this problem exists? |

| 8. Make specific inquiry about conduct and rule following | Any problems with behavior?

Any problem with following classroom rules? Is he disruptive? What do you think is causing the problem? |

| 8a. Ask for elaboration if #8 is remarkable | How big of a problem does this seem like?

Why do you think this problem exists? |

| 9.Make a specific inquiry about mood and anxiety | What’s his mood seem like?

Does he seem anxious or worried? |

| 9a. Ask for elaboration if #9 is remarkable | How big of a problem does this seem like?

Why do you think this problem exists? |

| 10.Make a specific inquiry about atypical actions or thoughts | Notice anything unusual about him? |

| 10a. Ask for elaboration if #10 is remarkable | How big of a problem does this seem like?

Why do you think this problem exists? |

| 11.Double back for a reconsideration of a social-emotional problem | Now that we talked awhile, other thoughts about Brian status or his situation? |

| 12. Summarize what you have been told to assure there is no misunderstanding | Correct me if I’m wrong, but it sounds like you are describing a student who might have an anxiety problem. |

| 13.Thank the teacher and indicate how to convey any additional thoughts or novel observations. | Thanks. We can’t make sense out of things like this without expert teacher input.

Shoot me an email if anything else comes to mind. |

Here’s something you might do your skill development. Look at the HR Worksheet you learned about in Chapter 2. How might a new worksheet look for Brian as contrasted with the one completed for Franklin (the Chapter 2 case)? Much was learned from these two teachers in Brian’s case….probably enough to permit you to entertain working hypotheses. This should not be surprising. After all, teachers are child-oriented professionals versed in social-emotional development. They are also experts in instruction. After just a few years in the classroom, most teachers have seen students with every imaginable combination and permutation of success, failure, interest, disinterest, cooperation, resistance, attention, distractibility, worry, comfort, regulation, and dysregulation. What’s more, teachers are frontline; they can address student concerns as contemporaneous witnesses of fact. They observe students within a peer-group context where typical age-related behavior can be distinguished from problems (DiStefano, Kamphaus & Mindrila, 2010).

What’s more—and this point is far from trivial–teachers’ observations possess ecological validity. When Ms. Madison witnessed a behavior of concern, she would have done so in the real world of a school campus, not the artificial world of a professional’s office. Her observations, thus, may help nail down a particular school-centered hypothesis. In contrast, she may confirm that other behaviors (matching a competing hypothesis) have been seen. Back-and-forth discussion can enable nuanced considerations; maybe Brian’s problem appears only in certain campus situations but never in others. When teachers are initially unsure about the presence of certain behaviors they may need to watch closely for a few more days in advance of another face-to-face discussion with the school psychologist. It’s easy to see that school psychologists are uniquely located to capitalize on ecologically valid information provided by school personnel. Clinic-based practitioners struggle to access classroom information like this.

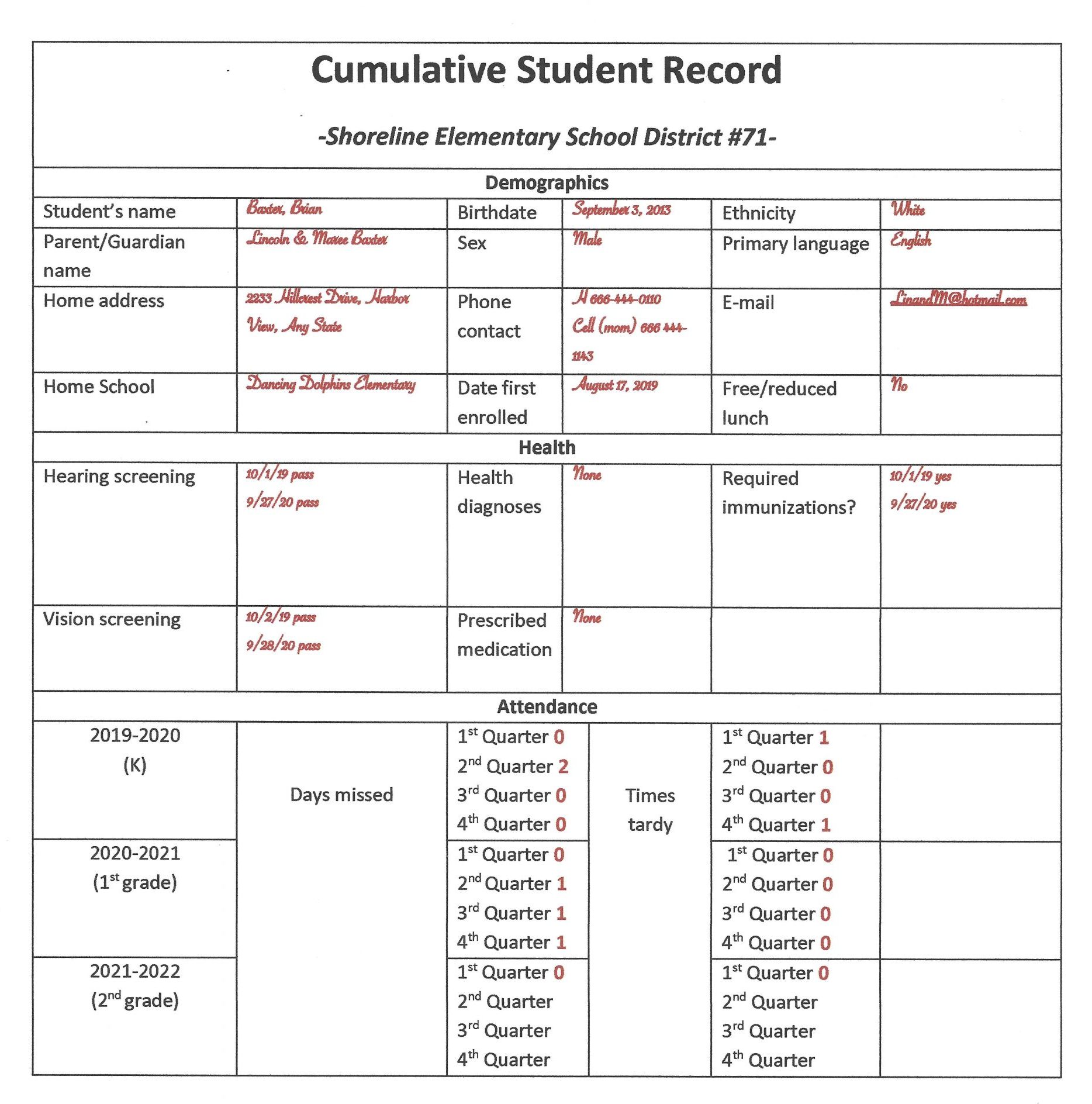

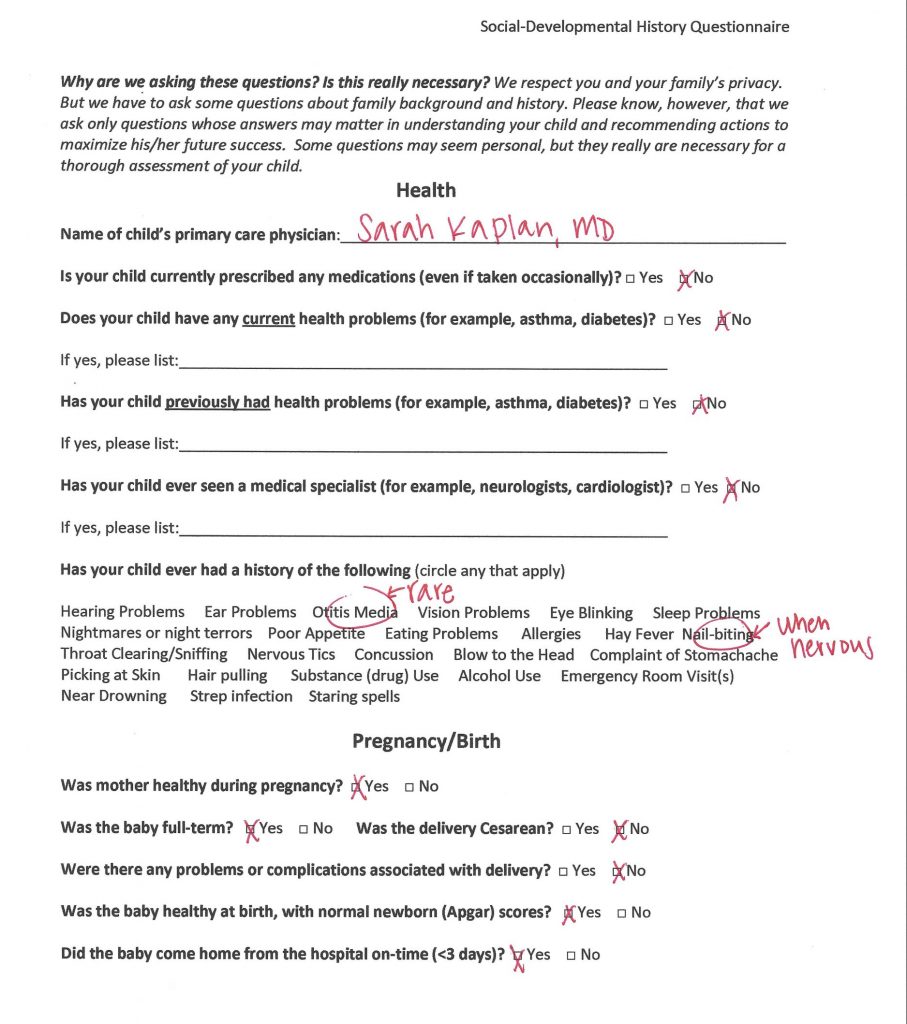

Cumulative File (Folder)

At one time, cumulative folders were literally folders (often manila in color). One existed for virtually every pupil enrolled in a United States school. Now, of course, many are electronic. As Figures 4.2 and 4.3 indicate, diverse information can be housed here. Typically included are the following: demographic information, general health information, results from vision and hearing screening, attendance information, group achievement tests scores, report card marks and indication if a separate special education file exists. Among all of this, sometimes you will find something to help generate new hypotheses, to assist in dismissing incorrect hypotheses, or to help confirm an already-strong hypothesis. Sometimes, unhappily, information found here is not particularly helpful. One never knows; you are encouraged to examine, reflect, and assume little a priori regarding prospective value.

Consider further Brian’s case. His school career has been so brief that two teachers (i.e., Ross and Madison) can describe much of its trajectory simply from memory, perhaps diminishing a need to seek much from the cumulative folder itself. But for older students whose school history extends over years, folder-derived information may prove more enlightening. This is true in part because potential informants (e.g., parents, former teachers) may remember only vaguely about earlier academic struggles, failed vision screenings, semesters characterized by poor attendance or many tardy arrivals. In contrast to often spotty recollections, a cumulative record might verify that parents remembered (or misremembered) their son’s grades, his attendance patterns, etc. Certainly, any time there is deteriorating academics, social functioning or attendance, school psychologists should consider going directly to the student’s records to check out the objective information placed there. Similarly, cumulative records can prove invaluable for documenting adverse educational impact, a routine requirement for special education eligibility. For example, when confirming adverse educational impact, school psychologists typically look at report card marks, attendance patterns, and high stakes test performances. How to use each of these three sources of information in special education decisions is discussed in Chapter 10.

Note that for now Brian shows only a slight problem on high stakes tests. But Brian is just a second grader whose history includes hardly any such assessments. A word of caution is in order about group-level test scores. Consider just why school psychologists invest more trust in individually-administered academic achievement test scores. Scores from individual achievement tests are apt to be quite valid. In contrast, group tests scores are sometimes marginally valid (or even frankly invalid). This is especially true for students with compromised attention, limited motivation, or poor listening skills. It is precisely these students who may fail to understand directions, give up too easily, and lose their place on an answer sheet (and hence bubble in responses in the wrong row). They may also become overwhelmed with test anxiety. In other words, threats to validity are common when students with social-emotional problems sit down for group-level testing. Perhaps it’s best for school psychologists to consider this old maxim: “High group achievement test scores confirm that the student either possesses skills or sat next to someone who did. Low group achievement test scores say relatively little.” All of this proves relevant because group achievement testing is a vast national enterprise. In fact, nearly all students now take routine group tests or those deemed high stakes (students’ personal progress or the status of their school riding on the resulting scores). The following website provides information about each state http://www.time4learning.com/testprep/

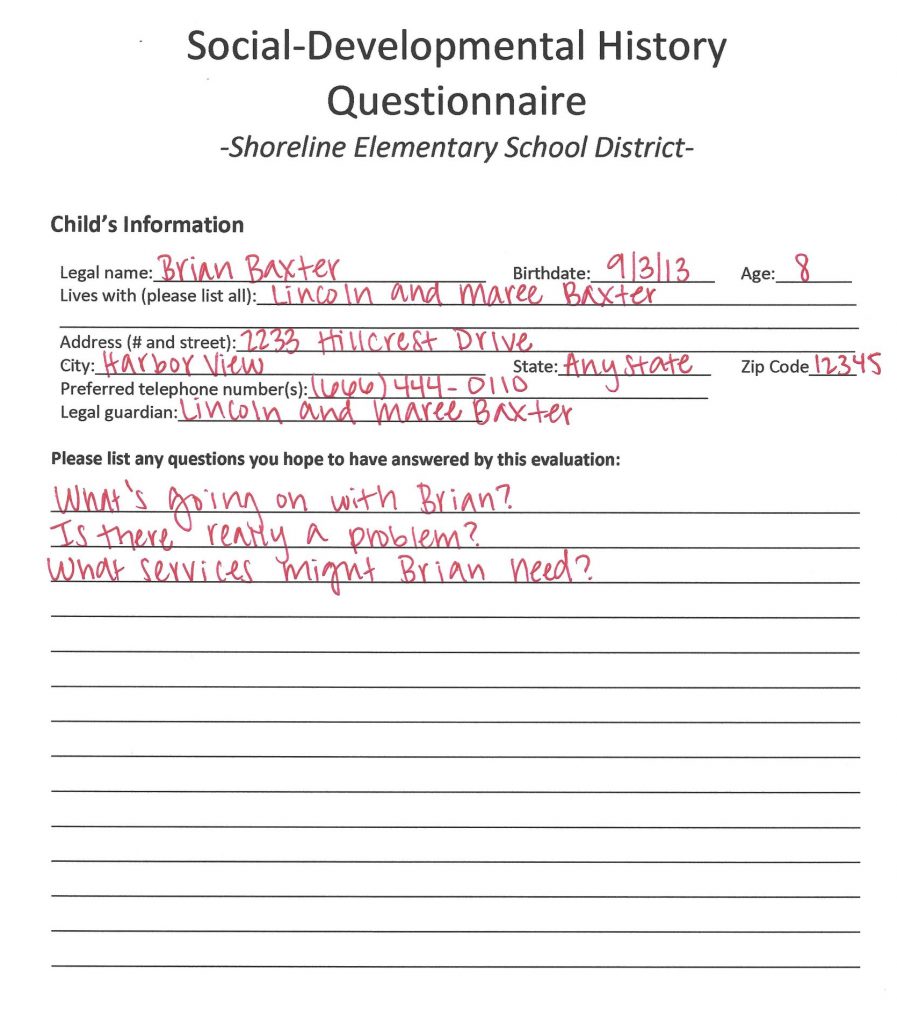

Health information is also routinely found in school records, either the cumulative file or a separate file held by the school nurse. Back to Brian’s case. What about the prospect of a health problem that might explain the behaviors seen at school? There are no listed health problems, and Brian has no prescribed medicine (at least none taken during school hours). Thus, his teachers’ concerns are probably unrelated to health. Health problems, however, are common, they can impact schooling, and teachers may not even know that they exist. Critically, there is evidence that when educators are kept in the dark about the existence of a health condition that they tend to conjure up common school explanations or those from folk sources. For example, Wodrich (2005) found that “poor parenting” and “laziness” were sometimes blamed for classroom productivity problems among students with epilepsy or type 1 diabetes mellitus, two conditions associated with variable classroom attention and work incompletion (see Wodrich, Hasan & Parent, 2011). Research confirms that there is often scant awareness among teachers, even special education teachers, that epilepsy is associated with mental health problems (Wodrich, Jarrar, Buchhalter, Levy & Gay, 2011). It is important to recognize that chronic health problems can engender emotional difficulties and undermine effective behavior, especially when the brain is directly or indirectly affected (Wodrich, Jarrar & Etzl, 2020). Among common chronic health conditions that impose educational risk are the following: asthma, diabetes, cancer, epilepsy, sickle-cell disease, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and a host of others.

Consider just one of these educationally relevant pediatric conditions that might be documented in a student’s file, epilepsy. Now reflect back on what you learned in Chapter 2 about quantifying risk of a discrete condition (e.g., depression, ADHD). In other words, how might a school psychologist estimate whether epilepsy actually matters to a student’s schooling? As you saw in Chapter 2, if two facts are available, the rate of a problem (e.g., ADHD) in the general childhood population and the rate of the same problem among children with epilepsy, then relative risk (expressed as a ratio) can be calculated. In fact, children with epilepsy have been found to experience depression at four times the rate of healthy peers and anxiety at 5.7 times their rate; so too for externalizing psychopathology (e.g., 5.3 times the risk for conduct disorder; Russ, Larson, & Halfon, 2012). Nearly one-quarter of children with epilepsy have been found to experience ADHD, about a four-fold increase over population prevalence rates (Cohen, Senecky, Shuper, Inbar, Chodick, Shalev & Raz, 2012; Russ, Larson & Halfon, 2012).

These numbers convey two important points. The first is that categorical risk can be quantified, not just thought about qualitatively. School psychologists’ phrases like, “Maybe there is a chance of depression being associated with this student’s epilepsy,” can be supplanted with “I was already thinking about depression, but that hypothesis now seems about four times more likely in light of the presence of epilepsy.” Of course, this is the Bayesian approach (updating probabilities with new information) you learned about in Chapter 2. Consequently, a probability nomogram can accommodate health information like this. The second is that several ratios conveying relative risk can be considered side by side. Epilepsy is associated with ADHD, anxiety, and depression. Intuitively, depression may seem a more plausible risk (i.e., recurrent seizures might foster discouragement and pessimism). But data show ADHD to be just as over-represented as depression among those with epilepsy. Anxiety, in turn, is even more over-represented. There’s more on this later in the chapter.

Although these numbers may be easily grasp, their genesis remains elusive. Some illnesses themselves mimic a mental health problem and some mental health problems are simply comorbid with, but separate from, particular illnesses (Wodrich, 2020). At other times the burden of the child and her family coping with a health problem causes compromised adjustment. Of course, in some instances several factors coalesce to produce social-emotional problems among students with a diagnosed health problem. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover health problems at school, but school psychologists may want to consider authoritative websites such as from the National Institutes of Health https://www.nih.gov and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control http://www.cdc.gov. Also, worth considering are books prepared with a school emphasis: Ronald Brown’s 2004 Handbook of Pediatric Psychology in School Settings and Allison Dempsey’s 2020 edited volume entitled Pediatric Health Conditions in Schools: A Clinician’s Guide for Working with Children, Families, and Educators.

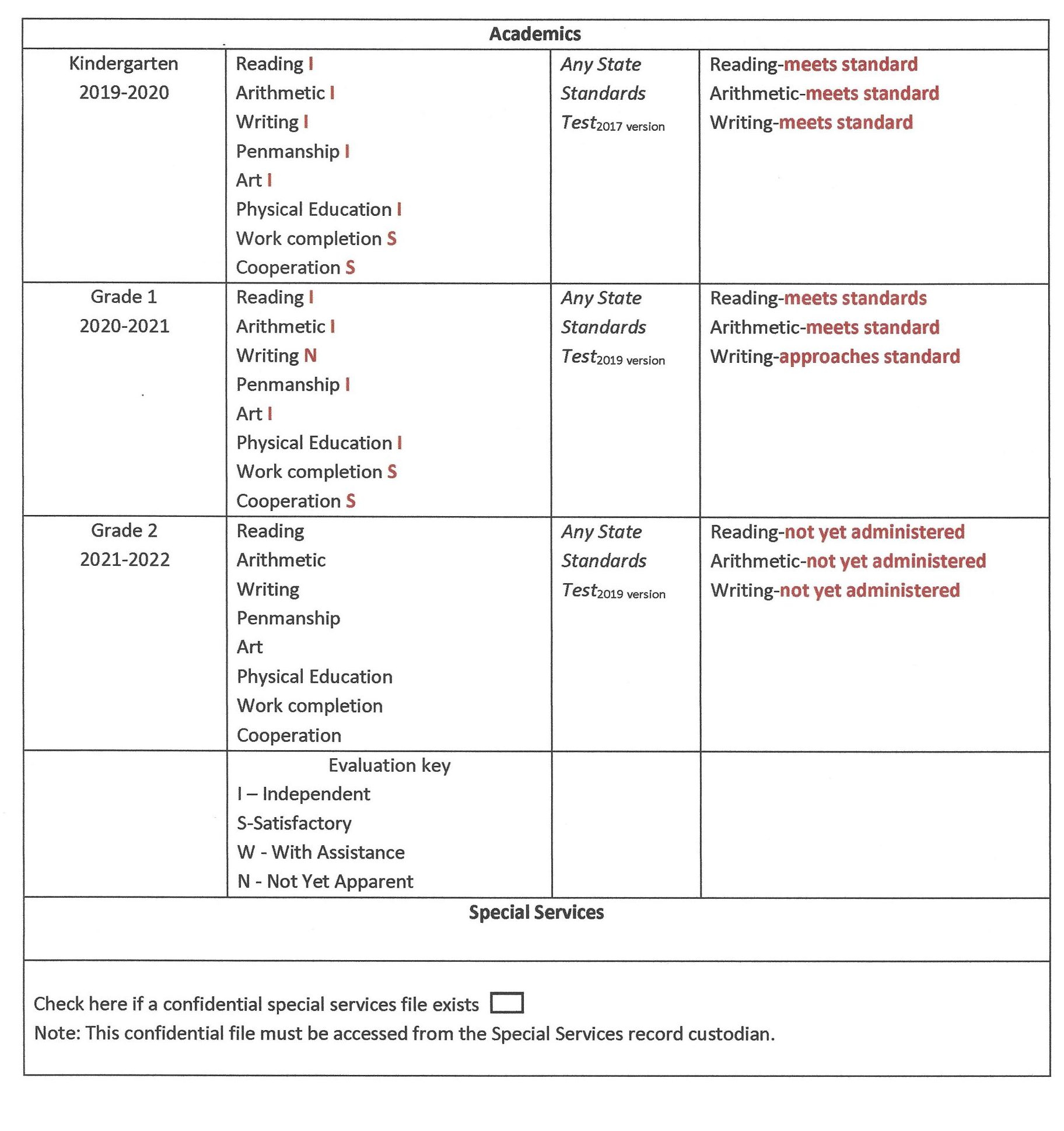

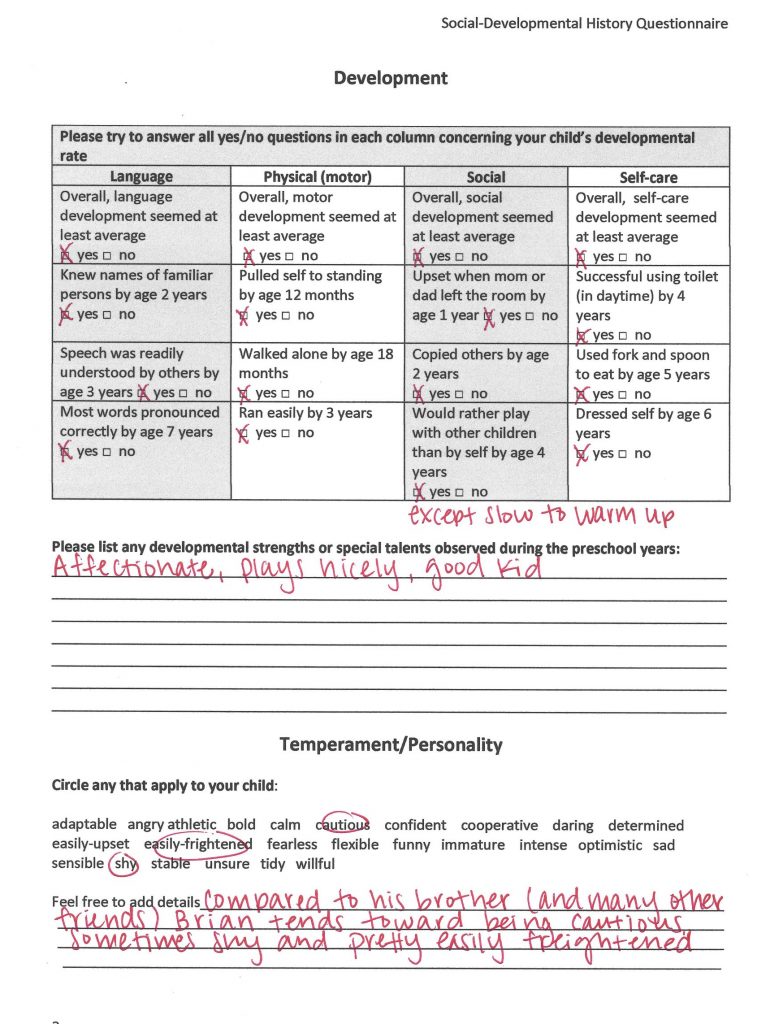

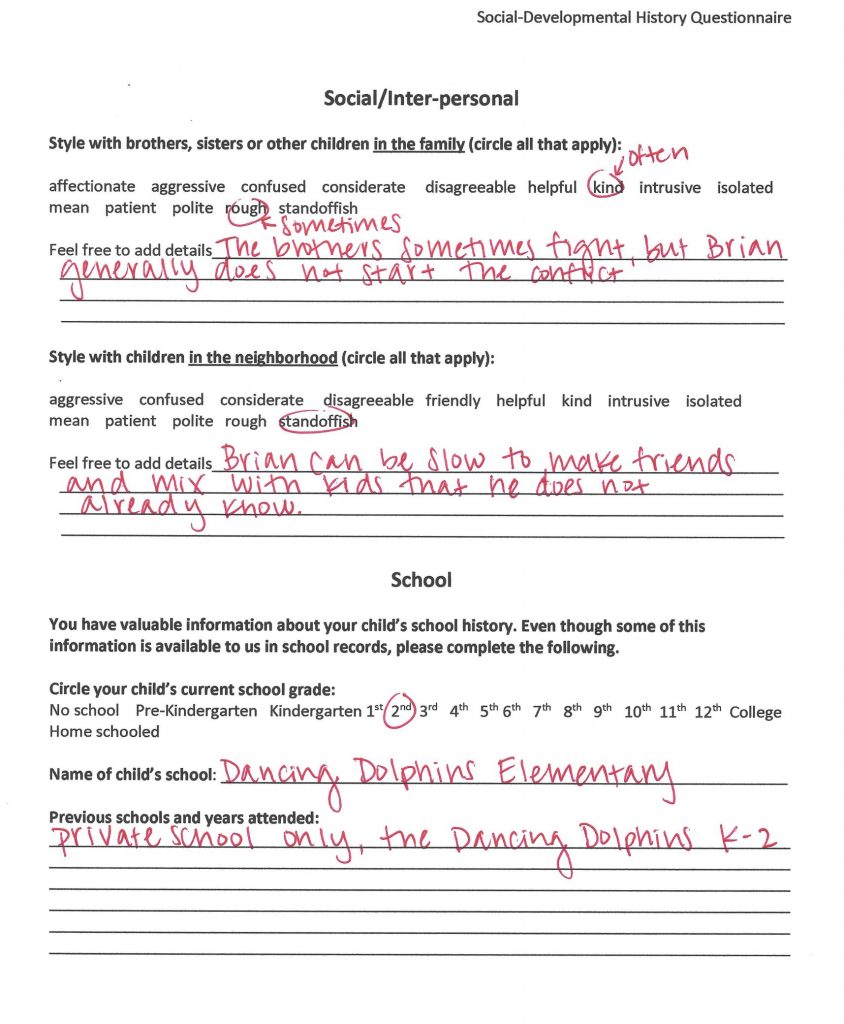

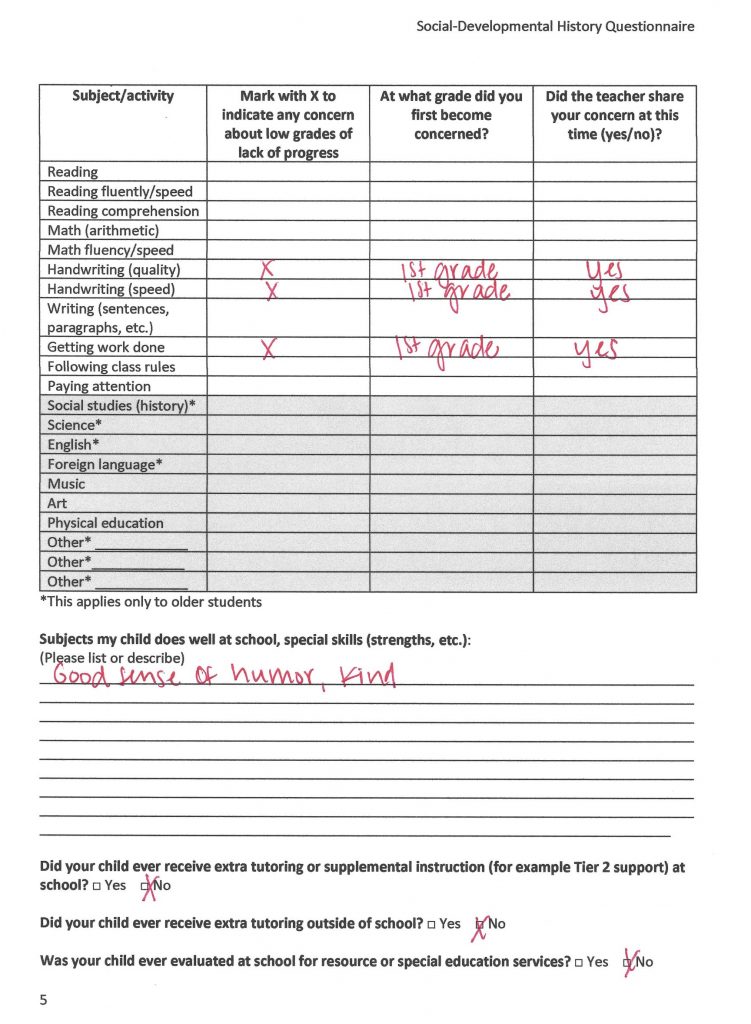

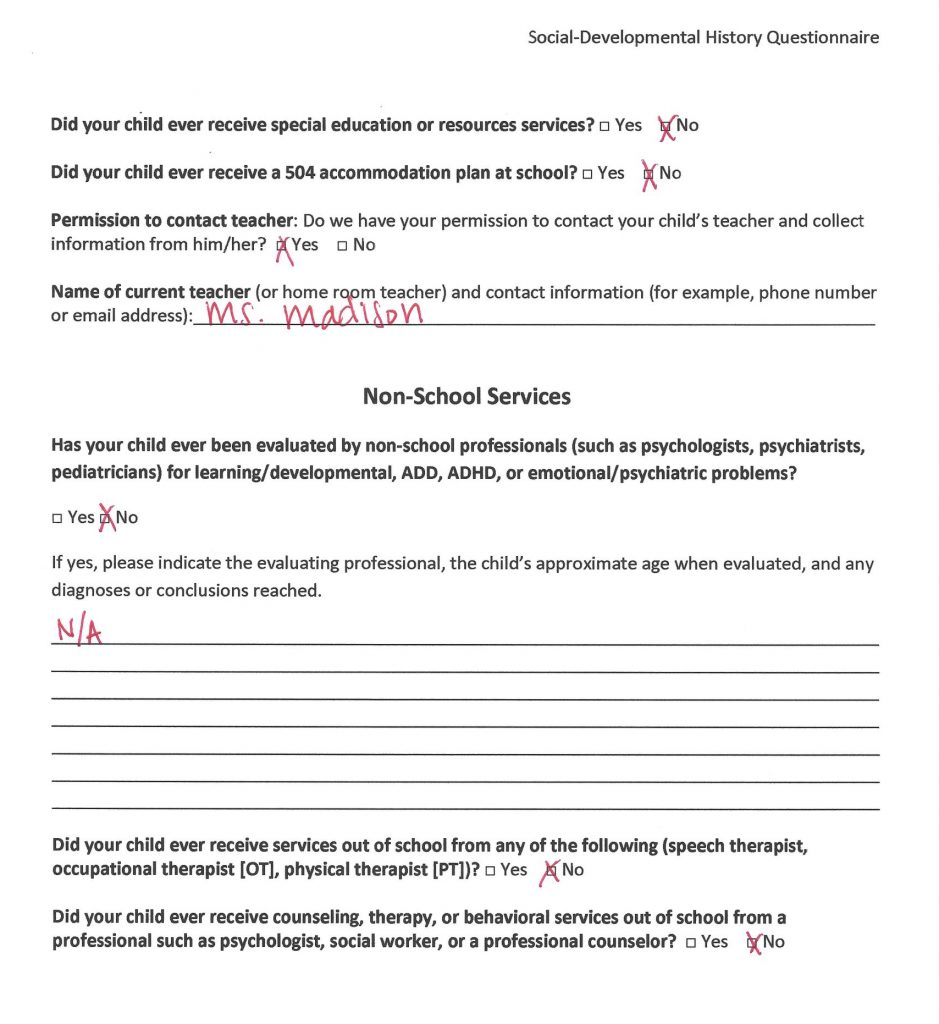

Parent-Completed Pre-Evaluation Social-Developmental History Forms

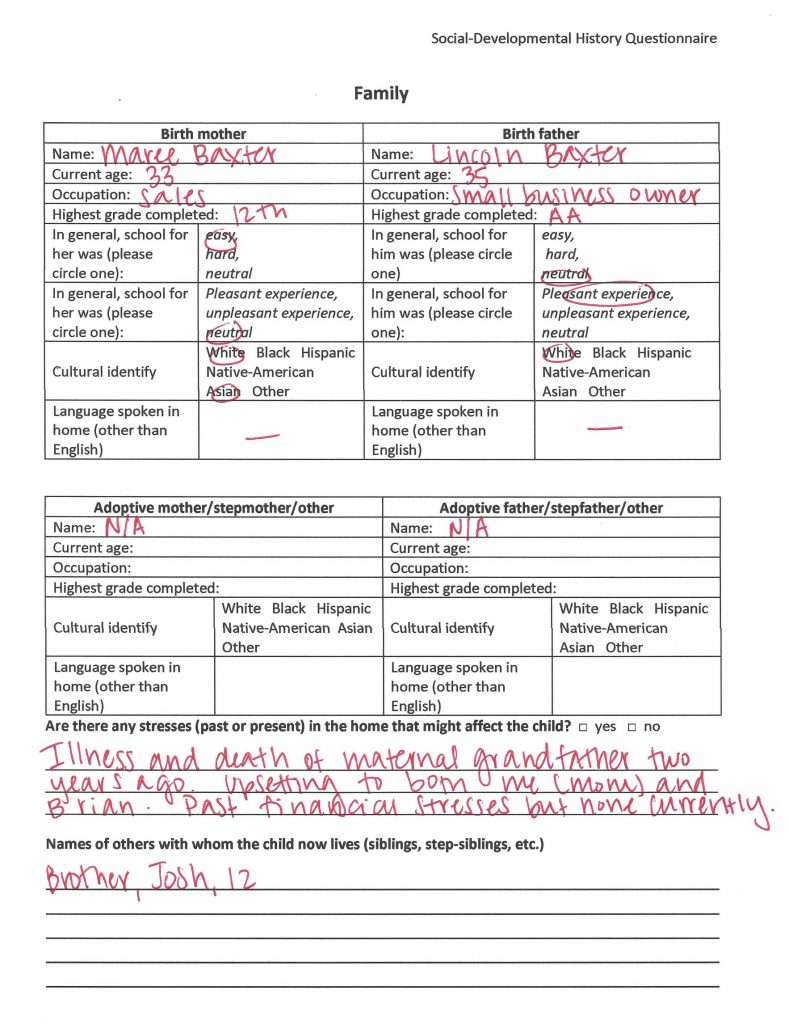

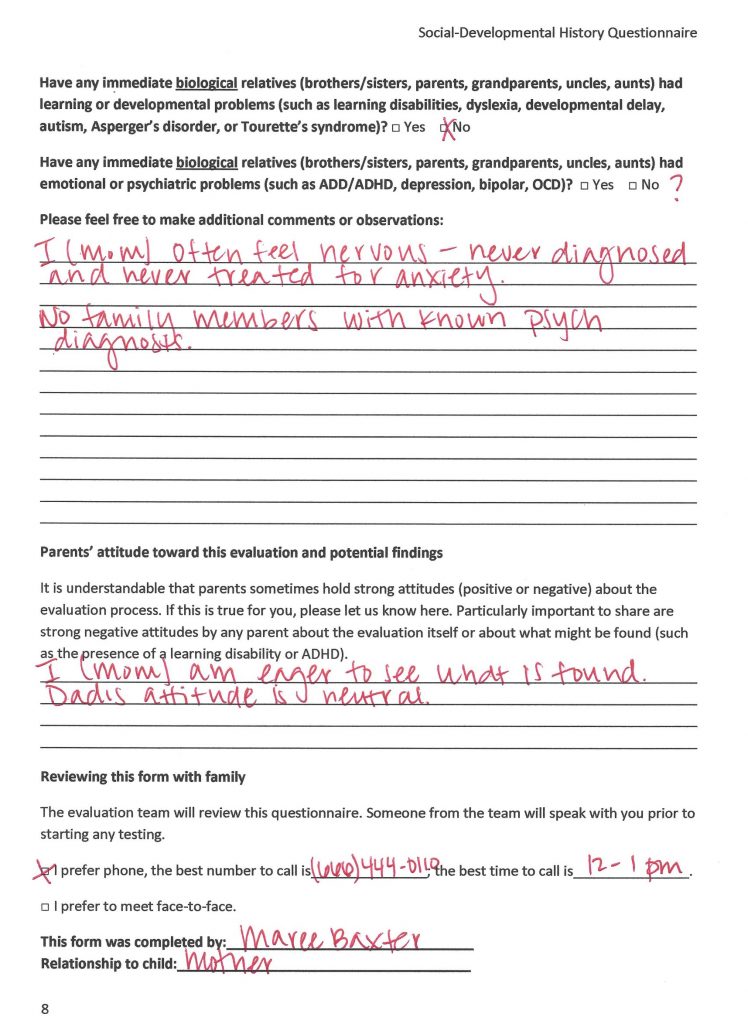

At some point, often after customary school sources are exhausted, school psychologists turn to information from parents and guardians. It’s no surprise that like teachers, parents possess a wealth of information. But how do you get it? One method is by use of a standard form containing questions about health, development, family, socialization, interests, conduct, and daily functioning. Some schools opt for commercial versions (e.g., the BASC-3 Structured Developmental History; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015). Other schools devise their own versions (see Figure 4.4 to 4.11 for information about Brian Baxter). For some school psychologists, forms like these stand alone. They are read, information is gleaned, and that is it. For other school psychologists, the forms are read and follow up parent/guardian interviews (via phone or in person) are routinely conducted. For now, simply read what is written on Brian’s form.

Parent Interviews (for Background Information)

A review of Brian’s parent questionnaire (Figures 4.4 through 4.11) indicates that his parents have already conveyed a lot in writing. This is often true. Unfortunately, it is not always true. Sometimes parents withhold information, sometimes they don’t understand questions, and sometimes they are simply incapable of writing well enough to impart intended disclosures. Thus, face-to-face (or telephone) discussions with parents can often clarify. It’s true that a conversation, even a brief one, can sometimes confirm, disconfirm, augment, contextualize, and nuance the contents of a pencil-and-paper form.

Also, when it comes to the value of speaking with parents, school psychologists are encouraged to slow down and think about the big picture. There can be substantial (sometimes life-altering) implications associated with some referral questions. This is obvious when there are questions about special education eligibility. This determination might, on the one hand, permit special services that rescue a floundering school career or, on the other hand, brand a student as “disabled,” changing how his teachers and family henceforth conceptualize him. Referral questions like this boil down to quasi-legal determinations of whether the student has a disability and whether that disability mandates services. In light of that reality, is it reasonable to make judgments about a “disability” without working closely with the student’s primary stakeholder, his parents? Maybe special education is not at issue, but the presence of a significant mental health problem may be. Is it reasonable to make judgments about the presence or absence of clinical depression, for instance, without speaking to someone who has known the child and interacted with him every day since his birth? Many psychologists, especially with clinic-based experience, are puzzled why school-based evaluations sometimes marginalize parents. If questions about a mental health disorder were posed in a clinic, minimizing parental input would be considered nonsensical. Should professionals in schools do less than their clinic-based counterparts? Thus, please consider making parents full partners in the social-emotional assessment of their child.

Now is a good time to read through Brian’s Social-Developmental History Questionnaire. As you do so, you might note in Figure 4.6 that parents describe their son as “slow to warm up” and as “cautious.” What did parents mean by this? For example, how often may parents see Brian acting cautiously? How long have parents observed cautiousness? How concerned are parents about this behavior? Is it seen as debilitating or a merely inconsequential observation? The same type of questions also apply regarding parents’ comment that Brian engages “nailbiting when nervous” (Figure 4.5). Parents, perhaps uniquely, can fill in details and provide context.

Family history merits special consideration. Many school psychologists seem to find inquiries on this topic uncomfortable. As a result, they pose skittish questions or avoid the topic entirely. A tangible rationale might help. That is to remember from what you saw in Chapter 2 regarding a severe mental illness, schizophrenia. To reemphasize the topic’s importance, recall that an affected sibling represents an eight-fold increased risk of schizophrenia. In fact, positive family history represents a risk for most mental health diagnosis found in DSM-5 (Knopik, Neiderhiser, DeFries & Plomin 2016). And, it is easy to envision the practical advantages of facts about family history entered into the middle column of of a probability nomogram. But in 2021, most school psychologists do not use nomograms. Similarly, most won’t access precise ratios related to family history. Even though this may be true, thinking carefully, slowly, and logically about the value of family history is advised whenever diagnosticians think categorically.

In truth, questions about their a family’s history of mental or developmental disorders puzzle some parents and, seemingly, annoy others. Happily, other parents see questions about family history as a welcomed chance to share information. Unfortunately, school psychologists never know which type of parent they will confront. Well then, how might this delicate topic be handled? It’s often smart to first carefully establish rapport, and then somewhat later remind parents that the process is intended to understand and help their child. For example, in light of the material provided by Ms. Baxter in Figure 4.11, some school psychologists might say something like: “I know the questions like this can seem intrusive, but science has learned that much like stature and eye color, tendencies in our behavior can be inherited. This is the reason for asking about ‘learning problems’ and ‘nervousness’ among family members as part of Brian’s evaluation. Could you share a few details about your comments that you often feel ‘nervous’ but have never been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder?”

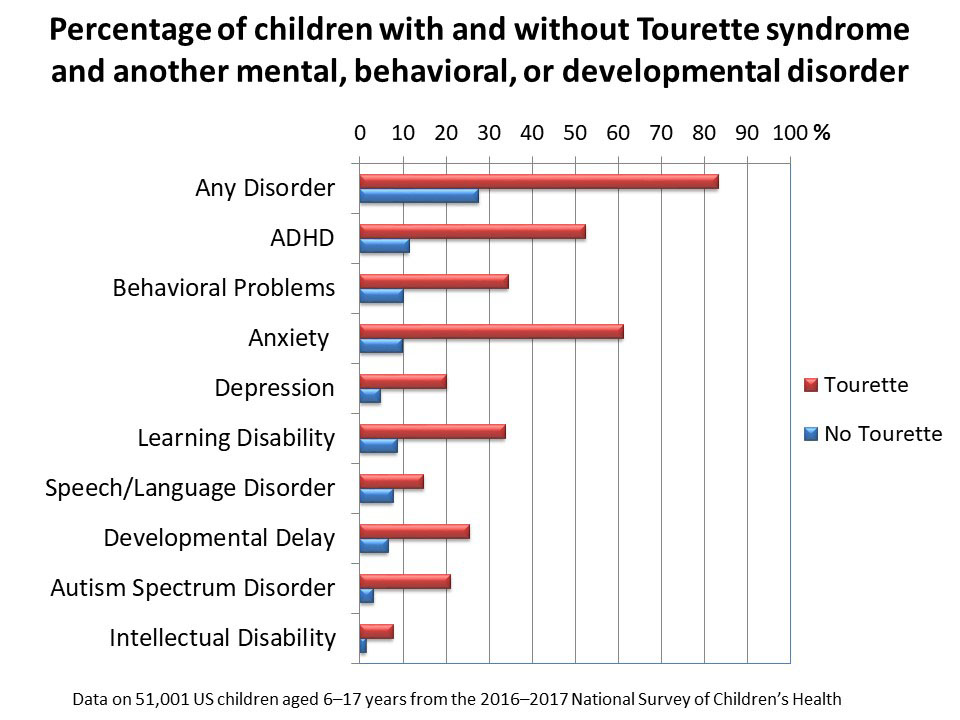

A prior diagnosis, such as found while collecting background information from parents, affords similar possibilities to think quantitatively. In other words, a fixed (first) diagnosis can help you consider whether or not another (second) diagnosis is more or less probable. This is fortunate because sometimes a diagnosis is already known (such as from an outside evaluation), as is information about the rate of comorbidity. At other times, a specific diagnosis is self-evident to the school psychologist as a student is observed and interviewed. Tourette syndrome is a case in point. The vocal and motor tics that define it are readily recognized by school psychologists with just a bit of focused training. Interview of parents can substantiate the presence of tics, document their history and speak to any tic-associated impairments or distress. But it is relative risk associated with Tourette syndrome that may matter the most. In other words, even when school psychologists forego formalizing a diagnosis of tics (or Tourette syndrome), their observations of these phenomena can help guide their thinking about the presence of other conditions that they may acutally diagnose. Examine the extensive list of learning and psychiatric problems comorbid with Tourette syndrome in a research study whose results appear in Figure 4.2 (you saw this figure earlier in the Skills Workbook). Examining the rate of various conditions, such as ADHD or anxiety, proves instructive. First, determine the rate of each of these conditions (ADHD, anxiety) in Figure 4.2’s non-Tourette’s group. Second, determine the rate of each of these conditions for the Tourette’s syndrome group. The ratio of these two values indicates the relative risk. Simply put, the presence of Tourette syndrome is associated with relative risk of ADHD greater than 5.0; greater than 6.0 of anxiety. As you will discover in later chapters, these risk ratios are often higher than DLRs derived for some popular ADHD or anxiety scales! This implies that we need to be careful to avoid overvaluing rating scale scores while undervaluing information pertaining to comorbidity.

Continuing to learn from parents’ comments, there are considerations associated with important events in the child’s life (i.e., critical things that transpired in the past or contemporaneously). For example, a history of trauma or noteworthy stress can sometimes be learned while collecting background information. Examples of questions from the Structured Developmental History (Figures 4.4-4.11) might provide information about stress or trauma. These include those related to: a history of serious illness or chronic health conditions (e.g., seizures), current or prior language problems (e.g., stuttering) or peer problems (e.g., being bullied), and so on. None of these was present with Brian, but they often are. That said, theoretical formulations coupled with empirical research suggests that a history of exposure to stress and/or a history of exposure to trauma may be more common and more consequential than envisioned earlier. For these reasons, experts (Grant, Carter, Adam & Jackson, 2020) advocate routine inquiries with parents about stressors that may exist now in their child’s life or may have been present in the past. Included would be those related to major events (death or separation from a major attachment figure, a previously-confirmed history of physical or sexual abuse), minor (microaggression related to a stereotype; death or separation from a peripheral figure) as well as systemic stressors (e.g., community violence). The rationale is that the presence of such stressors strongly predicts both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology (Grant et al., 2020). Chronicity and intensity of any stressors would also logically matter. Recognizing when stress exists may also inform treatment. Simply put, when a child’s problem is stress induced, treatment logically involves stress reduction or stress management (or both).

Related, but distinct, is the topic of trauma. The same authors (Grant et al., 2020) propose that a history of trauma be routinely addressed when speaking with parents (as well as with youth). You will see how to do this in Chapter 9 when the topic of student interviews is covered. Research suggests that it is insufficient to merely check on the presence of formal PTSD symptoms (such as some of those that you will see in Chapter 7 when narrowband tools are covered). Instead, it is exposure to trauma rather than the presence of formal PTSD symptoms that best predicts negative outcomes, such as the student later participating in risky behavior (Grant et al., 2020).

Cultural and Linguistic Considerations Regarding Background Information from Parents

Collecting background information is one of the first places where school psychologists confront important linguistic and cultural considerations. A few are mentioned here: (1.) linguistic factors that might constrain collecting information from parents, (2.) cultural values, concepts, and practices that may limit communication and constrain understanding, and (3.) in-group vs. outgroup implicit bias that may affect trust.

Linguistic Barriers

Envisioned two school psychologists plying their trade on the vast, sparsely populated Navajo Nation of Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. The first school psychologist is Martha Yazzie, a Diné (Navajo), who grew up on the reservation and is both proficient in the Navajo language and deeply cognizant of its complex culture, beliefs, and traditions. The second school psychologist is Savannah Smith, a European American, who grew up in Chicago and who is only this year starting to provide services on the Navajo reservation. Now let’s engage in a thought experiment. Assume that both women meet a family in Chinle, AZ, the Navajo Nation’s largest city (population 4,819). Each of the young parents had attended college off the Navajo Reservation, and each grew up in households were English was spoken almost exclusively. Still, both understand a bit of Navajo. Now assume that each school psychologist in this thought experiment conducted a face-to-face parental interview concerning this young couple’s Diné child. The chief complaint is disruptive classroom behavior. How easy is it for each school psychologist to communicate with parents? Do the two professionals enjoy equivalent (or near equivalent) ability to garner information via inquiry when one speaks Navajo and one does not? Maybe yes, maybe no.

Now envision the same two school psychologists with a different Diné family but with identical concerns about disruptive classroom behavior. This time the family lives in remote Nazlini (31 miles from Chinle) where the last census tallied a mere 489 inhabitants. Also, in contrast to Chinle, which is routinely teeming with non-Navajo tourists visiting the famous Canyon de Chelley National Park, Nazlini’s residents encounter fewer outsiders. This time care and custody of the student rests with grandparents, both primarily Navajo speakers and both strong adherents to traditional ways. Reflect on these realities for a moment. Even if the Nazlini grandparents (assume that they are L1 = Navajo; L2 = English) were entirely committed to tell Savannah Smith everything they knew about their disruptive grandchild, they may sometimes lack the English words and phrases to do so.

In linguistic situations like the latter, or when parents speak Navajo exclusively, interpreters might be needed to learn about the student’s development, her health and her behavior at home. Importantly, interpreters solve some problems (i.e., permit otherwise entirely blocked conversations) while introducing other problems (e.g., changing the level of rapport and slowing the pace of information exchange; Lopez, 2000). Parents might be able to disclose, but the addition of a third party might either facilitate or inhibit genuine information sharing. In light of realities like this, detailed guidelines have been formulated for the ethical and effective use of interpreters (Nahari, Martines & Wang, 2017). School psychologists should familiarize themselves with these guidelines if they find themselves in Ms. Smith’s situation, or comparable situations involving hundreds of languages. The following are advocated for interpreters: (1.) genuine proficiency in the non-English language being employed (including at the level of dialect), (2.) training and experience in actual interpretation in the field, (3.) knowledge of the role of an interpreter plus sensitivity to the interactions between service providers and non-English-speaking parents, (4.) competence in both the culture of the non-English-speaking family and the school, (5.) capability to remain neutral and maintain confidentiality so as to promote effective information collection (Lynch, 2011). Interestingly, a recent survey of practitioners suggests that use of interpreters is indeed common but their preparation is not held in high regard (i.e., just 21.1% of school psychologists judged interpreters to be either “well” trained or “very well” trained; Vega, Lasser & Afifi, 2016).

This is all fine, but many readers say to themselves that they are unlikely to ever practice on the Navajo Nation. Given that this is true, it remains nonetheless wise for everyone to consider the sheer number of non-English-speaking families that comprise the 21st century United States. A convenient case in point is the city of Los Angeles and its slightly more than four million residents. A 2006-2010 survey found many individuals who described their ability to speak English as “less than very well.” https://www.laalmanac.com/LA/la10.php. For illustrative purposes consider the following list, each of which has more than 1,000 non-proficient-English-language speakers residing in L.A.

- Arabic

- Armenian

- Chinese

- French

- German

- Hindi

- Hungarian

- Italian

- Japanese

- Korean

- Non-Khmer

- Other African languages

- Other Asian languages

- Other Slavic languages

- Persian

- Portuguese

- Russian

- Spanish

- Tagalog

- Thai

- Urdu

- Vietnamese

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, this list would grow to at least 185 if less-common languages (i.e., those numbering from just a few to several hundred speakers) were added https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2015/cb15-185.html[retrieved December 9, 2019]. Clearly, school psychologists practicing in the city of Los Angeles can expect to encounter real challenges accessing even basic information from some parents (indeed, nearly 57% of homes in Los Angeles have a non-English language spoken within its walls; Rumbaut & Massey, 2013). The numbers tell just part of the story because sometimes neither an interpreter nor a bilingual school psychologist is involved. Indeed, how much trust should one assign to information disclosed by a parent who speaks English “less than very well?” How do school psychologists (and other assessment team members) discern which parents are sufficiently proficient to describe their child for themselves? What trust should be assigned to information glean via interpreters? Answers are elusive. Minimally, however, school psychologists should be cognizant of linguistic factors when collecting background information from parents in general and when an interpreter in particular is involved (National Association of School Psychologists, 2015). This is the reason the HR Worksheet includes a prompt for you to attend to cultural and linguistic factors as you consider background information.

Cultural Barriers

Language proficiency and interpreter usage, of course, is just one consideration. Culture also unmistakably matters. And cultures, such as found on the Navajo Nation, can constitute dramatic departures from the routine cultural world inhabited by most European Americans. Interestingly, this reality sometimes makes its way into popular culture, such as via the bestselling fictional works of Tony Hillerman (e.g., The Shape Shifter, A Thief of Time, Skinwalkers). Hillerman’s protagonists, Navajo police officers Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee, convey to the public the richness of Navajo traditions and the distinctiveness of Navajo beliefs as they themselves struggle to bridge cultural divides in the practice of law enforcement.

More to our point, the cultural divide is also substantial for European American mental health professionals who come to the reservation. A psychiatry resident, Suzanna Kitten, conveyed how difficult it is to come from outside to provide services on the Navajo reservation (Kitten & Erlich, 2011). Dr. Kitten was struck by surprising notions of what is historically sacred (e.g., corn); styles of interpersonal interaction (e.g., minimization of eye contact, use of extended warm-up intervals during which things like the status of the family’s livestock herd is discussed); influences on behavior (e.g., spirits of deceased relatives may be influential) and even historically-important interventions, including for mental health problems (e.g., a purifying sweat-lodge ritual might help resolve prior traumatic episodes). Moreover, Navajo clan membership is vitally important. Clans, however, are traditionally organized matrilineally (Willging, 2002). In distinction to European American culture, it has been the identity of one’s mother and grandmother that proves most significant. Now think again about Ms. Yazzie and Ms. Smith. How might cultural considerations handicap their practices? Are prospective handicaps likely equivalent when speaking with a young Chinle family compared to speaking with a more senior Nazlini family?

There’s more. Cultural beliefs and native language sometimes coalesce at the level of individual terms used to describe mental health symptoms. This suggests that culturally-tailored terms may be needed whether a psychologist is speaking with a rural Navajo family, an urban Chilean immigrant family, or a suburban traditional Cameron family. For example, Kohrt, Luitel, Acharya and Jordans (2016) reasoned that there is a need for culturally appropriate idioms that are “locally salient” rather than standard psychiatric nomenclature when assessing mental health problems. In fact, working in Nepal these researchers found strong sensitivity and specificity statistics when depression related items (e.g., regarding anhedonia, depressed mood, self-blame) were translated into familiar Nepali idioms. Even so, cultural barriers sometimes remained despite the best efforts at locating native idioms.

Is there an easy way around these barriers in places like the Navajo Nation? Perhaps. Social-emotional assessments conducted by a Native American school psychologist might seem to solve all of these problems. But first-hand accounts from such professionals suggest otherwise. Consider the words of a practitioner. “Being a Native American psychologist is confusing and stressful at times. Being a Native American school psychologist practicing in a Native American community, I question my professional background” (Dauphinais, Robinson-Zañartu, Charley, Melroe & Bass, 2018, p. 1 & p. 24). Nonetheless, it is unescapable that Ms. Yazzie would hold advantages over Ms. Smith with virtually every Navajo family. This is likely to be especially true with traditional families, like the example of the Nazlini grandparents. Still, Dauphinais and colleagues point out that a Native American psychologist cognizant of the local milieu is prepared to parse genuine, cross-cultural behavior problems from those that merely reflect local socialization practices.

Implicit Bias

Bias is a risk whenever you interview parents. In fact, bias toward those from other racial/ethnic groups is common (perhaps universal) among humans (Clark, Liu, Winegard & Ditto, 2019). Our collective evolutionary history has predisposed us to engage in some activities (e.g., affiliation, trust) more readily and more fully with our own family than with others. This is sometimes referred to as the “kinship premium” (Curry, Roberts & Dunbar, 2013), which over the millennia conferred an adaptive advantage and consequently permitted the tendency to remain strongly represented in the human genome. Ethnic group membership can be envisioned as an extension of kinship. It’s easy for Navajos to consider themselves part of the same group (in some ways a very large extended family), but to see European Americans as being outside this group. As such, an outside professional (despite earnest desire to serve and without conscious awareness) may hold biased attitudes about Navajo clients and Navajo parents. These attitudes need not be explicit nor available to conscious awareness, they may instead operate implicitly. This is a situation of ethnic incongruence, a phenomenon reported in the school psychology literature (e.g., Loe & Miranda, 2005). The critical point is as follows: “people in ethnically incongruent relationships may have less positive views of their relationship partners” (Thijs, Westhof & Koomen, 2012, p. 259). With limited awareness, Ms. Smith might harbor such views of Navajo parents and Navajo parents might harbor comparable views of her.

Bias (although not necessarily implicit bias) has been documented when White professionals provide health services to Black patients. Indeed, health care providers routinely hold mild to moderate levels of bias in favor of Whites over persons of color (e.g., see Hall et al., 2015, for a review). Again, this is presumed to happen without conscious awareness. The findings from this study represent just one more factor added to the two cited above, that might impede school psychologists’ information collection from families. But in-group and out-group status, bias, and interpersonal trust factors probably operate in all directions, not just when members of a dominant culture consider those who are not a member of that culture. It would be only natural for a Black family living in a relatively homogenous Black community to experience less comfort with and trust of a White provider than a Black one. Navajo families might have just the same hardwired tendency regarding European Americans. Germane to the current discussion, ethnic incongruence (i.e., a school psychologist from one ethnic group juxtaposed with a student and her family from another group) has been documented to be widespread in assessment situations. Loe and Miranda (2005) confirmed this reality fifteen years ago. The same is likely true today, perhaps even more dramatically as the country grows in diversity.

Of course, there is far more than evolutionary predispositions involved here. Anyone with even the most passing knowledge of American history must be cognizant of the centuries of broken agreements, land grabbing, systematic annihilation of language and culture, and even frank ethnic cleansing that Native Americans have suffered at the hands of European Americans. Even if less dramatic, parallel considerations exist for Latinos/Latinas. And even more obvious are the facts concerning African Americans. There are unescapable truths: nearly all of the ancestors of today’s Black U.S. population were brought to America as mere chattel, and even after emancipation endured harsh Jim Crow laws, voter suppression, economic discrimination, and (persisting far into the middle of the last century) barriers to interracial marriage and vigilante-style public lynching. In light of our shared human nature couple with our long-unbalanced racial group interactions, would a Navajo parent be expected to disclose as much to Ms. Smith as Ms. Yazzie? Might a Hispanic parent be expected to share the same information with a Hispanic school psychologist as her Anglo counterpart? Would a Black parent be expected to invest as much trust in a White school psychologist as a Black one? Answer for yourself.

Managing Cultural and Linguistic Challenges

Perhaps in an idealized world ethnic incongruence in assessment would be rare (even non-existent). This is utter fantasy. Consider the current realities. National survey data indicate that nearly half of U.S. students are non-White (nearly one-quarter are Hispanic and roughly one in eight are Black; Musu-Gillette, Robinson, McFarland, KewalRamani, Zhang, & Wilkinson-Flicker, 2016). Especially relevant linguistically, one study found that 27% of entering kindergarten students came from immigrant families (Sullivan, Houri & Sadeh, 2016). Critically, these numbers stand in stark contrast to survey data, which indicate that fewer than 10% of school psychologists are from racial/ethnic minority groups (Castillo, Curtis & Gelley, 2013). Setting aside ethnicity for a moment, consider the availability of bilingual school psychologists. The NASP website maintains a “Directory of Bilingual School Psychologists.” Looking at just a few of the languages listed above in the Los Angeles example, the paucity of targeted bilingual school psychologists is apparent from nationwide numbers. There are just three Armenian proficient school psychologists in the United States, two Hungarian speaking, five Urdu speaking, and four Tagalog speaking. https://apps.nasponline.org/membership-and-community/bilingual-directory/directory.aspx. This suggests that there may be too few Martha Yazzies on the Navajo reservation, resulting in the recurring need to count on some Susan Smiths. Use parallel logic to envision realistic rates of ethnic incongruity at diverse school sites across the United States. Pick whatever racial and linguistic minority you like. The conclusion is likely to be just the same; ethnic incongruities of all manner are bound to be abundant. What should be done?

A first suggestion is to achieve practice-related cultural familiarity, to the extent practical. In other words, anyone practicing in homogenous settings is obliged to learn at least the basics of the relevant culture. No less so than Ms. Smith in Arizona, a practitioner in a Somali dominated school in St. Paul, Minnesota, or a school psychologist assessing many Haitian students in Tampa, Florida, has work to do. Her job requires it in what is now termed “cultural competence.” Cultural competence is advocated in all spheres of school psychology practice by NASP. The same is true regarding the American Psychological Association via the following practice imperatives: (1). practice cultural humility, (2.) seek out resources, (3.) ask for help, (4.) engage with the community (Clay, 2019). https://www.apaservices.org/practice/business/ecp-column/cultural-competence?_ga=2.18313727.77529825.1575657866-1038729653.1405496452. [retrieved December 5, 2019]

A second suggestion for school psychologists is to consider detailed information about the cultural perspective of families as well as about themselves. This can go beyond simple ethnic incongruity. Pamela Hays (2016) offers a helpful rubric for characterizing a parent (or student) with whom you are speaking. The model is entitled ADDRESSING, the letters of which provide a helpful mnemonic for 9 critical dimensions:

- Age and generational influences

- Developmental or other Disability

- Religion and spirituality

- Ethnic and racial identity

- Socioeconomic status

- Sexual orientation

- Indigenous heritage

- National origin

- Gender

Examining each of these dimensions might help mental health professionals think reflectively about culture. Specifically, by carefully examining their status in each area they may gain perspective on their personal characteristics and better appreciate gaps in their own life experiences. In addition, examining parents (and students) on these dimensions might help them “consider the salience of multiple cultural influences and identities with their clients” (Hays, 1996, p. 332). For example, you might envision the points at which either Ms. Yazzie or Ms. Smith might match (or fail to match) families from whom information might be sought in Chinle or in Nazlini.

A third suggestion concerns before-the-fact acquisition and preparation of interpreters. In other words, interpreters should be secured, vetted, and taught the ropes long before you need them. This can prove difficult. Someone (probably at the level of the school district central office) needs to assume responsibility for determining high-frequency, venue-specific translation needs (i.e., document the most common languages found in each community) as well as devise a plan when a low-frequency language situation arises. Thus, in Portland, Oregon, Russian interpreters should be located in advance (Russian is the most common language spoken after English and Spanish in Portland). But a school psychologist in Portland also needs her school district to possess a plan of action that can be triggered rapidly when a rare Indonesian family is encountered. There’s more. If school districts recruit a general cadre of interpreters, special vetting is still needed to assure preparedness to help during the special circumstances inherent in psychological assessment. Sufficient Thai proficiency to help a parent enroll a student in school or explain a bus schedule is not necessarily evidence of preparedness to ask delicate questions about family functioning or to maintain strict confidentiality. Consequently, interpreters probably need in-service training. Given the importance of the interpreter’s role, school psychologists should be prepared to insist on such training. Effective and ethical practice depends on it.

A final simple suggestion may also help facilitate open communication (and thus valid information collection). Anyone who has practiced for any time in the Southwest, Texas or California has probably witnessed a Spanish interpreter in action speaking with a Latino family. In meetings where this takes place, it’s striking how much more approachable a Spanish-speaking parent becomes if he or she utters something simple in English (e.g., “Nice to meet you.” at the outset of a meeting or “Thank you for your help.” at a meeting’s conclusion). Yet the same tendency to humanize oneself may never occur to school psychologists. That is, they may fail to utter even the simplest genuine greeting to a Spanish-speaking parent. It’s easy to learn to say a two-word Spanish greeting (buenas tardes) or a one-word Navajo greeting (yá’át’ééh). In instances of ethnic incongruence and reliance on an interpreter, something simple like this might also be advisable. Anyone practicing in Los Angeles might prepare herself to try the former, Susan Smith the latter. This represents just another chance to be “psychologically minded.”

Outside Professionals’ Reports

Not infrequently, background information sources include other written reports. In-house, these may consist of prior psychological reports or multidisciplinary assessments prepared as part of the special education process. These are easy to locate, often in a separate, confidential special education file. The usefulness of prior evaluations, however, varies. For example, a prior SLD-focused evaluation sometimes proves remarkable thorough and thus enlightens a current social-emotional assessment. Often, however, if SLD is the category of concern, school psychologists are apt to find a written report that is long on legalistic terminology, packed with test scores, but short on social-emotional substance. Nonetheless, reading in-house documents is mandatory.

Prior out-of-school reports prepared by psychologists also vary in usefulness. Their value often hinges on the referral question. For example, if an outpatient clinic shares a document compiled simply as a prelude to treatment, its contents may be scant. Perhaps there’s just an interview and scores from a broadband rating scale. Still, there may be some value for a school psychologist, such as looking for matches between the clinic’s conclusions and your emerging hypotheses. A clinic’s full-blown evaluation may be even more helpful. There is one caution for school-based readers of extra-school documents: don’t be too quick to judge the quality and style of what you read. When an outsider’s report looks dissimilar from your own report this does not imply that someone working in a clinic failed to do her job. To do so would be equivalent to someone working in a clinic abitrarily knocking your work. She may wonder, for example, why you generate so many pages, use so much legalistic jargon, and fail to even list a DSM-5 diagnosis. Her report may look alien (and inadequate) to you just as yours may look alien (and inadequate) to her.

Outside, or second opinion, evaluations about special education eligibility are a different matter. Independent educational evaluations (IEEs) fall into this category. IEEs are conducted when parents contest the findings of a school team’s special education evaluation. Often IEEs communicate no useful information able to assist you in answering your referral question. In fact, it is argued that these reports represent forensic or legal documents as much as they do psychological or educational documents (Breiger, Bishop & Benjamin, 2014). During the written report preparation process (see Chapter 14) school psychologists need to document outside reports (i.e., summarize them very, very concisely). But school psychologists are cautioned against counting on out-of-school workups to truly answer school-based referral questions.

Similarly, IEPs found in students’ files are often of limited value. Although these need to be investigated, one often gets the sense of examining mere documentation, service guarantees and a list of hoped-for outcomes, but not something that reveals much about a student’s behaviors or emotions. These are quasi-legal, administrative documents. In other words, it seems rare that reading an IEP prompts a hypothesis, diminishes one, or imparts a sense of the student.

Permanent Products

Permanent products are physical products associated with school tasks. In contrast to ephemeral observations or interviews, these student-generated artifacts endure until lost or discarded (thus, they are “permanent”). The tangible material ranges widely from arithmetic or writing worksheets of elementary students to home-work assignment logs and term papers of high schoolers. They are often used to exemplify student’s hands-on work, perhaps capturing a student’s best, worst, or routine work. Although review of permanent products is advocated as part of a classroom-based intervention plan (Sanetti & Collier-Meek, 2014), their application need not be confined to intervention. Rather, school psychology diagnosticians can tap these physical products to infer current skill levels, judge attention to detail and organization, and deduce a student’s consistency over time. Some parents even save permanent products spanning years.

In the case of Brian, for example, a school psychologist might seek writing samples. Evidence of labored penmanship, poor pencil control, and limited legibility might suggest graphomotor control problems. Logically, this hypothesis might lead to inquiries about Brian’s rate of written work completion compared to his classmates and/or his routine time requirements for writing task completion. Following this line of inquiry might suggest, in turn, questioning about either anxiety-related slowness on the one hand or written-work-associated frustration on the other hand (Wodrich & Schmitt, 2006).

The long view is sometimes enabled by examining permanent produces (especially when parents save work from earlier years). Work samples that demonstrate quality in middle school, for example, but show deterioration during high school provide grist for the hypothesis-generation mill. That is, academic problems that emerge early in school and persist might be deduced to be related to either enduring cognitive and information-processing problems or to chronic social-emotional difficulties. In contrast, late-onset academic problems are logically more related to mental health problems.

Background Information, Playing Second Fiddle

Contrast the esteem afforded background information with that of psychometric test instruments (which you will hear a lot more about starting in the next chapter). As you may already know, it’s common to find love affairs between school psychologists and their favorite psychometric instrument. School psychologists’ blogs, for example, are replete with requests for the professional community to clarify a puzzling test profile. If readers of these blogs reflect for just a moment, it is striking how rare it is to see any background information mentioned. Often, bloggers seem only concerned about the test scores found in their confusing case, as if test scores should stand alone. Maybe the preeminence of test scores starts with a BASC-3, the most popular of all psychological tests used by school psychologists. The BASC-3 is indeed impressive. Its various options include numerous subtest and composite scores, many graphic profiles and a lot of color found on its online (electronic summary) as well as in its paper, printed summary. But it goes beyond mere flashy printouts. Most test publishers are wise enough to package their products attractively, to advertise them widely, and to declare their merits in polished workshops. Virtually all publishers maintain websites coupled with 1-800 phone numbers to assure easy access to their products and to champion their virtues. But as you have already seen in Chapter 2, love affairs with psychometrics can lead one to overlook troubling flaws.

Realistically, collecting and using background information is far more prosaic, and sometimes more time-intensive, than simply deferring to rating scale scores. And, most publishers are reluctant to develop tools for background information collection; there simply is only a limited market (one exception is the BASC-3’s Structured Developmental History, Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015). Similarly, you won’t find workshops featuring the use of background information. These realities aside, background information often represents a veritable treasure trove. Background information can spawn some hypotheses, aid the dismissal or strengthening of others, and suggest that still others merit contemplation.

An Avalanche of Paper. What to Do?

As this chapter demonstrates, performing a social-emotional evaluation can trigger a paperwork avalanche. One wonders how to keep things straight as the HR process, for example, is followed. Unfortunately, there is no universal answer. Some school psychologists highlight critical information with one or more colors of highlighter (used either electronically or in hardcopies). Others use tabs. Still others make notes to themselves on a scratchpad. Some may adopt the HR Worksheet and make notes directly on it during the background information stage. It’s often helpful to see how things are done by more experienced colleagues. As you might suspect, after background information is collected, a second or third avalanche may be on the way following the use of broadband, narrowband, and self-report measures. Organization can become a real challenge. You are encouraged to devise, and recurrently tweak, your own organization plan.

Summary

School psychologists tap quite diverse sources of information to answer referral questions. Practicing on a school campus enables this. Working here affords access to student’s records, their permanent products, and teachers able to report first-hand observations and contextualize other information. In contemporary practice, there are abundant linguistic and cultural considerations that arise when background information is collected, especially those aspects that involve students’ parents and guardians. For most referral questions, no one piece of information stands alone. Instead background information dovetails with observations, interviews, and rating scales (all topics covered in upcoming chapters) to permit answers.