10 Emotional Disturbance and Section 504

Key takeaways for this chapter…

- It is essential to recognize referral questions that are administrative (quasi-legal) in nature and distinguish them from those that are not

- School districts are mandated to identify all students with IDEA-specified disabilities, plus all conditions requiring 504 plans, although school psychologists are not necessarily obligated

- The most commonly used categories related to social-emotional assessment are emotional disturbance (ED), autism, and other health impairment (OHI, when ADHD is present)

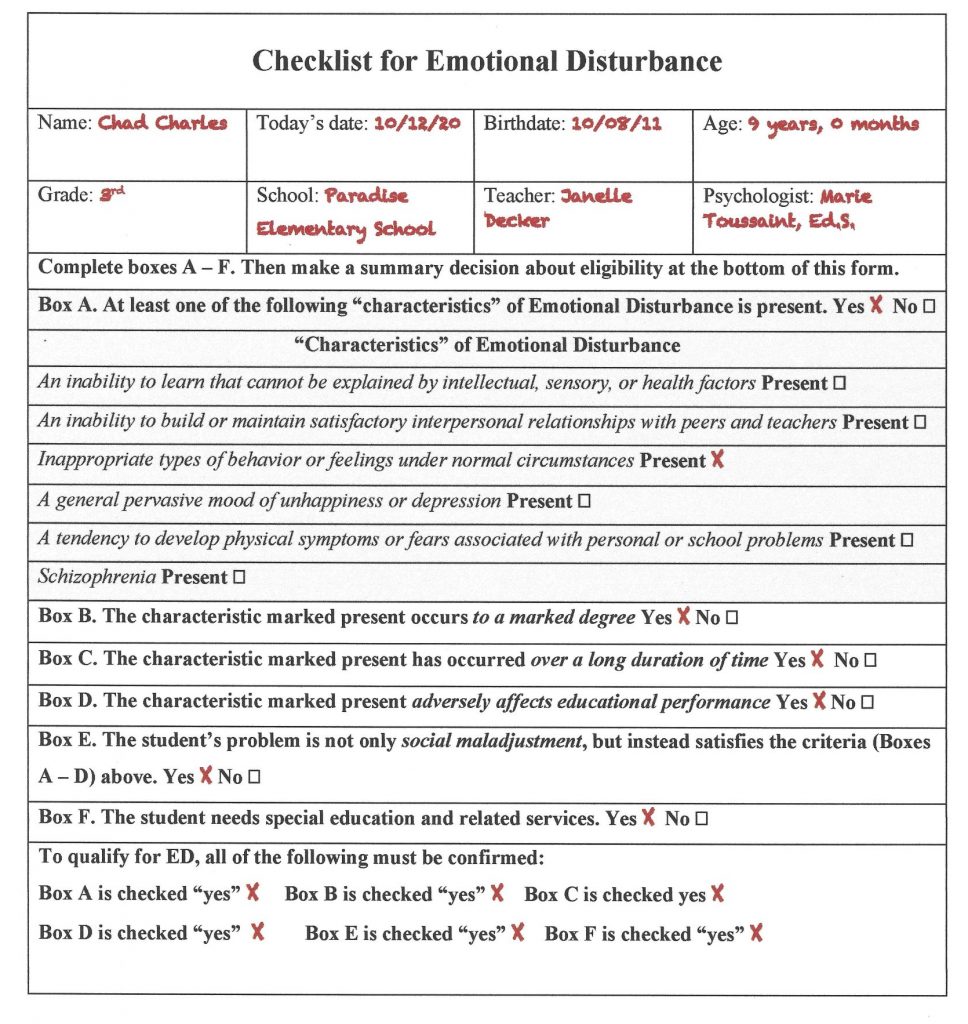

- Checklists can help school psychologists reflectively determine the presence of ED (as well as autism and OHI, covered in other chapters)

- The ED definition indicates that social maladjustment alone is insufficient evidence of a disability

- School psychologists are well positioned to influence eligibility judgments and to help guide post-evaluation educational planning

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- Franklin, no ED consideration

- Lauren, ED with low achievement test scores

- Mary, ED with suspended academic progress

- Robert, ED with school absenteeism

- Eloise, special education related services

Most school psychologists wear at least two hats. When they don the first hat, their role is much like their applied brothers and sisters in clinical psychology and counseling psychology. As such, they seek to understand the causes and progression of individuals’ problems, as well as how to alleviate suffering and improve quality of life. When they don the second hat, however, their role is quasi-administrative and quasi-legal. In the first instance, assessment is necessary to assist others with whom they consult. Clinicians figure out the nature of problems, the context in which problems occur, students’ strengths, and they make recommendations. Working in their clinician role, school psychologists also discover the dynamics of social-emotional situations and elucidate students’ personality characteristics. At times, they must also consider mental health diagnoses. Indeed, establishing a diagnosis is not trivial. This is so because a confirmed mental health diagnosis can clarify the etiology of a problem, its likely course (and whether it might spontaneously resolve), as well as proven, disorder-specific interventions. ADHD, for instance, is associated with brain dysfunction (characterize by impulsivity and executive dysfunction), its course is chronic, and it is treatable with established educational, behavioral, and psychopharmacological interventions. With their first (clinician) hat firmly in place, school psychologists are thus prepared to fulfill their ethical obligation, “the application of their professional expertise for the purpose of promoting improvement in the quality of life of students, families, and school communities (NASP, 2020, p. 39).

In contrast, with their second hat in place, school psychologists (and the multidisciplinary teams [MDT] with whom they work) fulfill legal responsibilities. They are protectors of students’ rights and they are guarantors of promised services. They need to be aware of relevant laws, policies, and rules to fulfill their provider role (Mire, Schoger & Ramclam, 2020). To be clear, however, the provision of mandated services is a responsibility of the Local Educational Agency (LEA), not necessarily a school psychologist. Nonetheless, Zirkel (2018) addresses the possibility that LEAs might delegate authority to school psychologists regarding implementation of parts of IDEA. Most important for this discussion is LEAs’ universal obligation to identify each student with an IDEA-defined disability and to provide them a free appropriate public education (FAPE).

The obligation to search for and identify eligible students is entitled Child Find. As a matter of practice, however, LEAs often invest MDTs and school psychologists with the responsibility for identifying students. Identification consists of documenting each student who falls into a disability category and offering appropriate services (in the form of an Individualized Educational Program; IEP). Emotional disturbance (ED) is one such IDEA category. Critically, however, ED in contrast to ADHD, as one mental health example, are conceptually and practically dissimilar from one another. For example, ADHD is a diagnosis with important scientific and clinical advantages lacking ED. As seen in the preceding paragraph, ADHD is a condition with a relatively homogeneous cause(s), natural history, and effective treatment. This is not true of ED. Unlike ADHD, ED arises from a multitude of causes, students with ED have no common natural history, and effective ED treatments are almost as diverse as the ED students themselves. ED is an administrative label, ADHD a clinical one.

The scientific notion of causation is also dissimilar for administrative labels and clinical diagnoses. Diagnoses, more or less, seem causative; not so for administrative labels. For example, elementary students with depression may be identified as ED. The logic is that depression causes educational problems sufficient to satisfy the criteria for ED. Students with ADHD, similarly, may confront educational problems sufficient to satisfy criteria for the OHI special education category. In these instances, either a diagnosis of depression or a diagnosis of ADHD would help explain a host of student behaviors (plus, coincidentally, the student’s eligibility for special education services). Conversely, the presence of ED fails to elucidate students’ behavior. Academic disengagement and withdrawal from classmates may spring from depression. This makes logical sense. It makes no sense, however, to describe a student as disengaged academically and interpersonally withdrawn because of her ED.

At the risk of oversimplification, the first school psychology role is one of a clinician. The second role is one of a gatekeeper. Try to remember, moment-to-moment, which is your current role. Regarding labels, try to remember just which type (administrative or clinical diagnosis) is the current topic of debate. As you will see in Chapter 14 (How to Prepare Written Reports) some psychoeducational reports (MDT reports) list two sets of labels: one administrative, another clinical. For example, for the same student there might be two categorical conclusions:

- IDEA categorization: Emotional Disturbance

- Clinical categorization: Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder-combined type

Likewise, school psychologists’ role clarification is best made explicit. This is often accomplished at the referral question stage (see Chapter 3). At the time of referral is when administrative-eligibility missions are distinguished from various clinical missions. The current chapter is all about duties associated with wearing the second hat. It’s about how to be a competent, conscientious, and equitable gatekeeper. The chapter covers the special education category of ED. Also addressed is section 504 of the Americans with Disabilities Act (simply referred to as section 504 in this chapter). Special education considerations pertaining to autism are covered in their own chapter (Chapter 11). The same is true regarding the special education considerations pertaining to ADHD (Chapter 12).

Emotional Disturbance

In this section, we conduct an in-depth analysis of the special education category of ED. The first goal is to promote a conceptual grasp of the category. The second goal is to introduce an algorithm for making sound case-by-case judgments about the presence of ED.

ED is Rarely Used Category

Let’s start with a basic question. How successful are schools in locating students with ED? After all, ED is a special education category for which LEAs must participate in special education-related Child Find. That is, school districts are obliged to locate and serve students with ED. Although there is no easy answer to the “are they being found” question, two sets of numbers suggest potential failings. The first is the rate at which U.S. schools actually identify students with ED. The second is the population prevalence of childhood mental health problems. Regarding the first, every year the U.S. Department of Education reports to Congress on the execution of the law that they passed, IDEA. This massive document is entitled, appropriately enough, the Annual Report to Congress on Implementation of IDEA. For many years, the Annual Report has confirmed the rate of ED students nationwide to be around 1%.

Although the ED rate seems slight, a logical question is how it stacks up against childhood mental health prevalence rates. In other words, when researchers use modern epidemiological techniques what do they find? A meta-analytic study (synthesizing findings from 12 large studies that used DSM and ICD criteria) helps provide an answer. Cross-study results indicate that 10.06% of youth experience a significant mental health condition (and accompanying impairment in one or more functional domains; Williams, Scott & Aarons, 2018). Now let’s juxtapose these two sets of numbers. Doing so seems to suggest the following: diagnosable childhood mental health problems occur among 10 times as many youngsters as receive special education services for emotional problems!

These stark facts beg the question, why are so few students identified? One possibility is that research findings, like those cited above, represent inflated population prevalence rates. This explanation, however, seems improbable. Epidemiology is an exceptionally refined scientific discipline that rests on rigorous methodology (see, for example, Das-Munshi, Ford, Hotopf, Prince & Stewart, 2020). And it is worth noting that empirical studies like those used in this meta-analysis are subject to painstaking critique and impartial peer review before publication. Thus, the 10% population rate is probably quite trustworthy.

A second possibility concerns educational impact. This line of thinking would reason that childhood emotional problems are indeed widespread, but they prove educationally trivial. In other words, there are a lot of students with emotional problems that amount to little at school.

A third possibility is that emotional problems are common and are educationally consequential, but that ED is so stigmatizing that schools avoid the category. Thus, school psychologists (and MDTs) find labels to use other than ED when special education services and an IEP are unescapable. This line of thinking would imply widespread default to the SLD category coupled with only infrequent ED label use, such as when there is no other viable means to secure needed services. Indeed, year after year, the Annual Report reveals that six times as many students are identified with SLD as ED.

A fourth possibility is that school psychologists lack diagnostic expertise regarding ED (whether real or perceived). According to this line of thinking, school teams might simple be ineffective at locating students with emotional problems (or unwilling to designate as ED those they do locate). Provocative research findings from practicing school psychologists hint at reluctance to identify. In an analogue study, 215 Pennsylvania school psychologists were given hypothetical cases that either met or did not meet ED eligibility criteria (Della Toffalo & Pederson, 2005). Among the 111 school psychologists who were given ED-eligible cases, 59 (53%) rated the objectively-eligible student has having little or no eligibility for ED services. This is troubling—ostensibly eligible students often might go unidentified.

There is still more. Like with other IDEA categories, ED is a category whose use requires parental consent. Perhaps some parents decline services even when a LEA (school psychologist and MDT) deems their child to be eligible. Furthermore, parents have the right to withdraw a student from services at their discretion. Parental rights are outlined in the following link from the U.S. Department of Education: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/d/300.300/b. Whether parental reluctance, a fifth possible explanation, contributes to the low rate of ED use is unknown. That said, there is no way to know which of the five possibilities covered above (or some other possibility) is most correct. In fact, there may be several factors working in concert. Nonetheless, there is one clear message–school psychologists and MDTs need to know how to accurately identify ED.

Racial, Linguistic, and Gender Considerations regarding ED Identification

Despite ED identification rates that are low overall, some groups are nonetheless disproportionately identified. This is most striking for African-American students, who when compared to students in general endure essentially a two-fold risk of ED identification. Conversely, Asian students have only approximately 1/5th risk of ED identification compared to children in the general population (see Table 10.1 for these and other groups). At first blush, these numbers might imply frank racial discrimination. The dominant culture may anchor behavioral expectations and tolerance for deviations from them. This line of thinking suggests that labeling takes place “viewed through a lens in which ‘inappropriate’ or ‘troubling behavior’ is defined by White, middle-class, mainstream normative conventions…” (Hanchon & Allen, 2017, p. 186). But it isn’t only racial/ethnic group membership, it is also students’ sex. Data show that many as 80% of students identified with ED are males (Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of IDEA, 2016), whereas these boys are mostly identified by school psychologists and MDT’s comprised of women. For example, a survey of NASP members indicates that 83% are women (Walcott & Hyson, 2018) and everyone is aware that in most elementary schools in the United States teachers are predominately women. Could this imply feminine intolerance for male behavior, some of which may actually be normative? There is no easy answer to these questions.

Chances are, however, that the genesis of disproportionality is more complicated than simple gender- or racial-associated intolerance (Hanchon & Allen, 2017). For example, a thoughtful analysis of the problem should include several considerations (see Sullivan, 2017). One consideration is whether ED-related special education services are themselves advantageous (i.e., services tangibly improve students’ learning and enhances their quality of life) or disadvantageous (i.e., services stigmatize without providing offsetting educational advantages). Another consideration is the origin of disproportionality. This line of thinking concerns whether various groups encounter different life experiences (e.g., greater exposure to trauma, lack of access to health and social services) that engender actual ED-related problems. For these reasons, it could be argued that rather than schools’ discriminatory identification practices alone, some groups encounter disproportionately high rates of ED identification reflecting real disabilities. Genuine gender differences may also arise from evolutionary factors. For example, much of the field of evolutionary psychology concerns adaptive pressures that operate differently on males and females (Buss, 2009). Perhaps biological-based, gender-specific behavioral predispositions, not just bias against boys per se, contribute to the high rates of boys in ED programs.

Whatever the origin, ED disproportionality compels sensitivity to one’s personal values as well as avoiding diagnostic practices that result in unwarranted disproportionality. Not the least of these potential threats to equitable practice is implicit bias. Stereotypes, such as concerning race or gender, operate to distort perceptions and alter actions (e.g. the nature of teacher-student interactions; Scott, Gage, Hirn & Han, 2018), even without conscious awareness. An antidote is to gain conscious awareness of one’s personal biases (which operate in the Automatic System) and rely on reflective practice and objective facts (the Reflective System). It is also to recognize that some groups are more apt to advocate for their children than others. Immigrant families, for example, may fail to understand the nature of special services or avoid requesting such services. This might be true, for example, of recent immigrants who would like to stay away from any actions that could be perceived by school personnel as demanding or “pushy.” Families here without legal status might avoid excess school contact (including questions about the child’s birth, development, and educational history that could inadvertently lead to inquiries about the family’s arrival in the United States).

Implicit racial bias may also exist. Consider two identical cases, one involving an African-American student, the other a European-American student. Let’s assume that both cases involve a male who is struggling to learn to read and who evidences periodic angry outbursts during academic work. Working hypotheses in the two cases might diverge fueled by stereotypes, including those outside of conscious awareness. The African-American student might be seen as dysregulated, angry, or out of control. Although a reading problem may exist, his behavioral excesses risk being most salient in the school psychologist’s formulation. An identical European-American student, however, might be envisioned to exemplify a reading problem as first and foremost. His reading problem, in turn, might have been expected to engender frustration at school. Both reading and behavior are recognized to be present but reading dominates the school psychologist’s mental construction of the European-American student’s case. In this contrived example, it’s easy to envision one student headed toward an ED designation, whereas a fact-equivalent counterpart might be headed toward an SLD designation (or no disability designation at all).

Table 10.1 Risk Associated with ED by Racial/Ethnic Group |

||||||

| Group | American Indian | Asia | African American | Latino | Pacific Islander | White |

|

Relative Risk (expressed as ratio)

|

1.68 |

0.18 |

2.08 |

0.61 |

2.35 |

0.96 |

| Source: Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of IDEA (2016) | ||||||

ED in the Eye-of-the-Beholder

An additional consideration is that ED evaluations routinely rely on informants (e.g., teachers). Algozzine (2017) argued that there are two distinct uses of teacher rating scales: (1.) in general clinical (extra-school) assessments, and (2.) in ED evaluations. When a child is seen in a clinic, for example, his teachers’ ratings of conduct or anxiety, whether high or low, may alter nothing about his school life. Sure, a teacher’s endorsement of psychopathology may convince a clinician to launch outpatient psychotherapy but there is little chance ratings will move that student to a different classroom. Things are different, potentially, when informants rate students who are candidates for ED identification. This time, characterizing a student with significant conduct or anxiety problems might reward a teacher with classroom supports or even removal of the student to another classroom. This sequence of events is argued to be particularly true when a teacher finds a student’s behavior personally bothersome.

Considerations like this prompted Algozzine to distinguish between ED’s stated purpose—”identification of disturbed behavior” and ED’s actual purpose—”identification of behavior that teachers find disturbing” (to themselves). Algozzine contends that current ED identification practices often make it too easy to reconceptualize teacher-student interaction dilemmas as intra-child emotional disturbance. The teacher beholds the child singularly as the problem. This is referred to as “the eye of the beholder” conundrum (Algozzine, 2017, p. 141). Furthermore, if you recall the fundamental attribution error (FAE) from Chapter 2, you might sense that teachers’ perceptions and associated actions in completing rating scales may occur without conscious awareness. It’s simply hard to recognize that troublesome student behavior might arise from complex interpersonal dynamics and environmental variables, not just psychopathology of a student.

Let’s turn back to the original contention—too much trust in rating scales. Is there actual evidence that informant-completed ratings are heavily emphasized when making ED determinations? The answer appears to be yes. For example, Allen and Hansen (2013) surveyed school psychologists to see if they used best ED-identification practices. Specifically, practitioners were asked about their routine use of the following evaluation components: (1.) teacher interview, (2.) parent interview, (3.) child interview, (4.) classroom observation, and (5.) behavioral rating scales (completed by two informants). ED assessments that used all five of these were deemed best practice compliant. The researchers were interested in each school psychologist’s routine practice (i.e., how many of the five evaluation components were used in at least 75% of their cases). Disappointingly, only 30% of school psychologists consistently used best ED practices. Equally troubling, 18% of school psychologists habitually used only one (or even none) of the listed procedures. Critically, when just one technique was used, that technique was always a behavioral rating scale.

Thinking back to the case of Franklin in Chapter 2, it is easy to envision rating scale scores from the two teachers with whom classroom conflicts had taken place. These two educators may have rated Franklin’s behavior as abnormal–rating scales could have pathologized Franklin. Teachers’ reactions to Franklin, not just Franklin’s personal characteristics, would presumably contribute to his ratings. Recall that in Franklin’s case, however, the school psychologist skipped the use of rating scales, relying instead on extensive interviewing and analysis of background information. It is noteworthy that Franklin’s school problems were ultimately attributed to teacher-student interactions, temperamental characteristics, and developmental changes (i.e., they were idiographic in nature). There was no need to resort to a mental health diagnosis (i.e., nomothetic considerations) or ED considerations.

The IDEA Definition of ED

The federal (IDEA) definition of ED follows (Table 10.2). Although each state is free to choose its own language and its own rules to help guide practice, the definition in Table 10.2 is similar to that found in most states.

Table 10.2 IDEA Emotional Disturbance Definition |

| Emotional disturbance means a condition exhibiting one or more of the following characteristics over a long period of time and to a marked degree that adversely affects a child’s educational performance:

(A) An inability to learn that cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors.

(C.) Inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstance. (D) A general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression.

Emotional disturbance includes Schizophrenia. The term does not apply to children who are socially maladjusted, unless it is determined that they have an emotional disturbance under paragraph (c)(4)(i) of this section. |

| Source: U.S. Government, 2004, Code of Federal Regulation, Title 34, Sec 300.8(c)(4)(i) and (ii) |

This definition has suffered harsh criticism. For example, Hanchon and Allen (2017) point out that today’s definition remains completely unchanged since 1975. Consequently, it is archaic and now out-of-step with more than 40 years of empirical research on behavioral disturbances and their impact on youth. As a case in point, there have been five DSM updates since initial construction of the ED definition, and each update incorporated public input, practitioners’ concerns, literature reviews, and field trials. Although scholars have critiqued some fine-points regarding school application of recent DSM updates, each new version is arguably better for school psychologists than its predecessor (Wodrich, Pfeiffer & Landau, 2008).

Now outmoded, the ED definition was not particularly strong to begin with. For example, its wording has been criticized as “imprecise, and at times inscrutable” (Sullivan, 2017, p. 249). According to Hanchon and Allen ED’s listed criteria “are insufficiently clear for systematic, fair, and unbiased implementation, essentially guaranteeing that high levels of inference, subjectivity, and supposition will enter into practitioners’ and teams’ decision-making processes” (2017, p. 179). In light of these criticisms, what are the exact requirements of the ED definition and where are its shortcomings? Let’s now take a look at the provisions of the ED definition, one by one.

Considering each ED Requirement

There are four obvious requirements included in the ED definition: (1.) presence of an ED characteristic (or a diagnosis of schizophrenia), (2.) evidence that the ED characteristic has been long present, (3.) evidence that the ED characteristic exists to a marked degree, and (4.) confirmation of adverse educational impact. Each must be satisfied before it can be judged that a student qualifies for special education and related services in the ED category. There is also a fifth element, the controversial social maladjustment clause, that some writers insist must be considered; if present, this element is said to contraindicate ED. We return later to consider social maladjustment. For now, the essential requirements are each considered.

Five “Characteristics” + One Diagnosis

There are five listed social-emotional descriptors (the ED definition refers to them as “characteristics”) that are the heart of ED identification. Practitioners often focus directly on these five as the central demand of ED identification. Thus, attention goes first to the middle of the federal definition. If you look at Table 10.2, this concerns the A – E. These five descriptors are comprised of everyday-language placed along side one technically-defined psychiatric diagnosis (i.e., schizophrenia). It is important to recognize that in 1975, when the ED definition was formulated, that there was no mental health classification system even remotely comparable to today’s large and detailed DSM-5. Instead only a few childhood mental disorders were enumerated in a slim manual entitled DSM-II (American Psychiatric Association, 1968). Specifically, childhood disorders included: withdrawing reaction, overanxious reaction, runaway reactions, unsocialized aggressive reaction, group delinquent reaction, and hyperkinetic reaction of childhood (a category later to become ADHD). Critically, however, DSM-II lacked diagnostic criteria, as well as information on prevalence, etiology, comorbidities, and natural history, all features now familiar to readers of subsequent DSM editions.

Perhaps for these reasons, federal officials authoring the ED definition failed to include DSM-II terminology (except for schizophrenia). Instead, the 1975 framers of the federal ED definition turned to the even earlier work of Eli Bower (1960). In fact, Bower’s earlier description of emotional problems, in a book he authored about mental health problems at school (including their prevention), ended up closely matching the ED’s definition five characteristics. Bower, years later (1982), complained that his research-based criteria had been corrupted by legislative and administrative attempts to placate various mental health and political constituencies. He argued that his work concerned mental health at school, not a template for administrators to define emotional disturbance. This fact highlights, once again, that ED is an administrative category, not a clinical (or scientific) concept.

In fact, the 1975 federal ED definition’s five characteristics (+ one diagnosis) as written prove to be logically inconsistent. Several of the listed “characteristics” seem to represent attempts to describe mental health diagnoses. In this sense they represent, more or less, students’ attributes (maybe even approximations of formal mental health diagnoses). But other characteristics listed in the ED definition are not characteristics at all (or approximations of diagnoses). Instead they describe functional impairments.

Let’s take a more detailed look. Two of the five characteristics of Table 10.2 appear to be DSM-related. Characteristic “D” describes (generally) depression. Thus, the following DSM-5 diagnoses would seem to satisfy characteristic D: persistent depressive disorder, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder 1 and 2, as well as cyclothymia. Characteristic “E” describes (generally) anxiety and psychosomatic disorders. Using contemporary terms (DSM-5), this would encompass conditions like following: separation anxiety disorder, selective mutism, specific phobia; social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, and generalized anxiety disorder as well as somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder. Remember, however, that many mental health professionals think broadly and concern themselves with general categories, not specific DSM-5 diagnoses (as you saw in Chapter 1). The same is true regarding the most common dimensions found in popular rating scales (e.g., BASC-3) and diagnostic interview techniques (the MINI-KID). Both of these assessment techniques, for example, enable detection of anxiety without mandating fine-grained determination of which exact type of anxiety is present.

But the IDEA’s ED characteristic “C” of Table 10.2 seems indistinct, whereas D and E seem at least somewhat distinctive. In fact, characteristic C does not encompass just a few DSM-5 diagnoses; it might be argued to match them all. Realistically, which DSM-5 diagnosis is not characterized by either “inappropriate types of behavior” or “inappropriate types of feelings?” The answer is probably none. Minimally, all of the childhood externalizing disorders of ADHD, ODD, CD involve inappropriate behavior. Similarly, at a minimum, all of the childhood internalizing disorders involve inappropriate feelings. Thus, for school psychologists who use the HR approach and find a probable DSM-5-related condition at the final stage on their HR Worksheet, systematically using DSM-5 criteria may be an excellent ED evaluation step. If the D characteristic could be confirmed by the diagnoses listed above; the same is true for E characteristic with the diagnoses associated with it. Characteristic C could be confirmed by virtually any DSM-5 diagnosis (backed by other assessment information).

But what about the sole mental health diagnosis specified in the wording of the ED definition, schizophrenia? As seen in Table 10.2, the ED definition is silent on the distinguishing features of schizophrenia or how to identify it. Schizophrenia is defined in DSM-5 (and ICD-10), but not elsewhere and certainly not in the ED definition. Consequently, school psychologists faithfully conducting ED identifications must be prepared to use DSM-5, at least in those rare instances when schizophrenia is a viable possibility. To do due diligence, school psychologists should arguably rule out schizophrenia when any of the following are found: a positive score on the MMPI-A schizophrenia scale, a strongly positive family history of schizophrenia, prodromal behavioral indicators during adolescence, and/or social, or marked functional deterioration. And, it might make sense to finally nail down ED characteristics C, D, or E by scrupulous use of DSM-5 criteria. Thus, for school psychologists considering characteristics C, D, or E (or the condition schizophrenia), supplanting vague ED definitional terminology with far-clearer DSM-5 criteria may be wise. Relying more on DSM-5 criteria is just the solution advocated by some critics of the ED definition’s dated and nebulous requirements (e.g., Hanchon & Allen, 2017).

Now consider two ED characteristics, A and B, that are logically dissimilar from the ED characteristics covered so far. Return to Table 10.2 and read characteristics A and B. Now ask yourself exactly where among DSM-5 diagnoses you will find these disorders. The answer is nowhere. That is because the ED definition has perplexingly interspersed diagnosis-equivalent characteristics (C, D, E plus schizophrenia) with characteristics (A and B) that describe adaptive impairments. For example, characteristic A is a generic description of academic failure. It is akin to one of the historic markers of SLD, inability to learn in the absence of obvious cognitive, sensory, health (or presumably) other factors (see Wodrich, Spencer & Daley, 2006). In this sense, ED characteristic A concerns a definition by exclusion. In other words, a school psychologist conducts an evaluation and finds a cognitively average student (e.g., one with composite IQ > 90). This student has no evidence of hearing or vision problems. He is free of chronic illnesses. He thus seems a strong candidate for either ED (criterion A) or SLD. There are criteria (and general descriptors) for SLD, but thinking of the identification of SLD and ED, one can see that the boundaries between the two IDEA categories are far thinner than envisioned by most diagnosticians. An emotional disturbance relying on the ED A characteristic is nothing more profound than saying “we don’t know why there is school failure, but the cause must be something emotional in nature.” Talk about vague.

ED characteristic “B” also concerns failure of adaptive functioning, rather than a social-emotional characteristic or a mental health diagnosis per se. Inability to build interpersonal relationships can be thought of as a consequence of a mental health condition, not its conceptual equivalent. In other words, it is an adaptive failure that might arise from conditions like depression, conduct problems, ADHD or autism. But there is no way to search DSM-5 to ultimately find a category called interpersonal failure. In fact, the very same interpersonal deficits can arise from sources unrelated to emotional or behavioral factors. Specific language impairments, for example, often provoke problems building interpersonal relationships (Crouteau, McMahon-Morin, Morin, Jutras, Trudeau, Le Dorze, 2015). Placing deficient interpersonal relationship in a definition of ED and assigning it equivalent status to anxiety or depression symptomology is logically deficient. Similarly, applying either ED characteristic A or B in clinical practice risks false positives. That is, using unexplained academic failure (characteristic A) or interpersonal problems (characteristic B) as the crux of an ED identification risks ED misattribution. This degree of imprecision represents a fundamental flaw in the ED definition.

This means that school psychologists must use all their tools (e.g., observation, interview, rating scales), coupled with their own good judgment, to confirm at least one of the listed characteristics. This is the best that can be done with this one set of requirements given the imprecision of the historical definition of five ED characteristics, plus one diagnosis.

“Over a Long Period of Time”

Critically for school psychologists and MDTs, confirming the presence of any one of the five (+ one) ED characteristics is necessary but insufficient for ED identification. The documented characteristic (or schizophrenia) must have been present for a long period of time, as seen in Table 10.2. The obvious intent is to prevent misidentification of students who are experiencing merely transient problems. In other words, assessing, documenting, and starting to serve a student makes little sense if her problem might soon resolve on its own. There is evidence that many childhood problems are not stable across time. For example, a Canadian study (Ghazan-Shahi, Roberts & Parker, 2009) found that many times initial diagnoses were absent on re-examination, and as time between initial and follow-up assessments grew there was progressively diminishing agreement. For example, a one-year (or shorter) gap between assessment one and assessment two had a .41 kappa (interpreted like a correlation coefficient), but a gap of two to three years had a very modest kappa of .19.

So, in light of the ED definition’s imprecise wording on this point coupled with the facts about stability immediately above, what actually constitutes “a long period of time?” No doubt opinions vary. One concrete way to add context, however, is to look at formal mental health disorders’ published duration requirements. In fact, the DSM-5 offers the advantage of explicitness and clarity on this matter. Table 10.3 includes timelines for several disorders that might affect school-age children. Of course, this information is only generally instructive. Still, it might suggest that durations of approximately three to six months could be applied logically for ED identifications.

Table 10.3 Information about Duration as Used in DSM-5 |

||||

| Minimum duration requirement for diagnosis | ||||

| 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |

| Separation anxiety disorder | X | |||

| Selective mutism | X | |||

| Intermittent explosive disorder | X | |||

| ADHD | X | |||

| Specific learning disability | X | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | X | |||

| Specific phobia | X | |||

| Oppositional defiant disorder | X | |||

| Schizophrenia | X | |||

| Tourette syndrome | X | |||

| Persistent depressive disorder | X | |||

| Disruptive Mood Disorder | X | |||

| Cyclothymia | X | |||

“To a Marked Degree”

A third requirement, as seen in Table 10.2, is that ED characteristics are present to a marked degree. Fortunately, school psychologists possess great ways to confirm the degree of a problem. They use standardized rating scales and look at standard scores (and associated percentile ranks). In other words, they use their nomothetic perspective to examine whether one student is an outlier by virtue of what is known about many students (i.e., those in a standardization sample). For example, characteristic ED D concerns depression. BASC-3 (teacher, parent, self) all contain a scale to measure depression. As you already saw, cut-scores (T-score > 60 = at risk; T-score > 70 = clinical range) are also available. Should they choose to do so, school psychologists can conduct diagnostic interviews with algorithms for establishing the presence of depression (e.g., Sheehan et al., 2010). Confirmation of a diagnosis via interview is ipso facto evidence of to a marked degree. That is, a child cannot be said to have a diagnosis of generalized anxiety disorder, for example, without also having anxiety “to a marked degree.” School psychologists are also blessed with comparable methods to establish adaptive problems. That is, ED characteristic A “inability to learn,” or ED characteristic B “inability to establish relationships” can also be established as present to a marked degree. For example, the BASC-3 Learning Problems scale taps various learning problems as evident to a teacher; the BASC-3 Social Skills may indicate behavioral deficits that preclude adequate relationships.

What’s more regarding ED determinations, school psychologists can use the HR Worksheet to assure comprehensiveness and to promote deliberate thinking. Whether the question is about the prospect of ED or something else, this approach prevents premature confirmation of any one hypothesis. It also compels the school psychologist to consider all sources of information and weigh each regarding her existing and emerging hypotheses. Of course, ED determinations are high stakes. They should only be made with multiple sources of information. And, because they are administrative, it’s advisable to use a checklist. You will see more about this later in the chapter.

“Adversely Affects a Child’s Educational Performance”

The final ED requirement, as seen in Table 10.2, is verification of adverse impact on educational performance. This requirement also causes confusion. The annoyingly inexact nature of the ED definition was just as troubling five decades ago as it is today. But the stipulation for adverse educational impact can be seen in a different light in today’s world. Then, as now, SLD represented the most-used special education category. ED took a backseat. Critically, however, SLD then was often established via ability/achievement discrepancy. Adequate IQ scores coupled with deficient achievement test scores were the SLD hallmark. This fact matters because many diagnosticians in the 1980s and 1990s implicitly envisioned adverse educational performance for ED to be established only one way–by low achievement test scores. In other words, ED educational problems were envisioned to appear just like SLD educational problems. Arguing against that narrow conceptualization, Wodrich, Stobo and Trca (1998) suggested that there were three ways to established ED-related adverse impact. Each was illustrated in a case. The three ways to consider educational performance may be just as compelling now as in 1998. They are: (1.) ability/achievement discrepancy, (2.) failure to continue to master the curriculum, and (3.) chronic absence from school. Let’s look at each. They hold importance because you may choose to use them in your practice to confirm adverse educational impact.

The first method may seem familiar because of its alignment with SLD methodology. Sometimes emotional problems interfere with educational achievement much like underlying information processing problems might. That is, emotional dysfunction represents ongoing and cumulative barriers to reading, math, and written expression skills. In cases like this, ability/achievement discrepancy is a straightforward method for documenting ED-related adverse impact on educational performance. This is illustrated in the case of Loren, an eight-year old with a four-year history of ADHD and ODD.

Despite Loren’s family being involved in an outpatient behavior management training program and his use of psychotropic medication, he evidenced persistent behavioral and interpersonal problems at home. When he entered kindergarten, his problems followed him. He seldom completed work, ignored his teacher and disrupted classmates. He had few friends and was often teased by classmates. Behavioral consultation with the school psychologist helped, but problems persisted. When finally evaluated at the start of fourth grade, Loren was found to have a WISC-5 full scale IQ of 101, no sensory or health problems, but low achievement test scores (KTEA-3) Basic Reading 79, Reading Comprehension 80 and Computations 77. Loren was judged to express ED characteristic B (inability to build or maintain satisfactory relationships with peers and teachers, one of the characteristics seen in Table 10.2), his problems were longstanding, severe (to a marked degree), and they were adversely affecting his performance in a most conventional manner (poor skill development). Loren’s case is easy to understand; his emotional problem led to uniform educational problems. He was concluded to meet the requirements for ED.

A second type of case, one lacking uniform academic skill impact, is a bit more complicated. Some mental health conditions are non-existent (or perhaps simply dormant) before they appear progressively more evident over months or even acutely over weeks (sometimes even days). Accordingly, academic skills may develop normally only to plateau with the onset of emotional problems.

This is exemplified by the case of Mary, a typically-developing fifth grader. For illustrative purposes assume that baseline psychometric scores existed even before any expression of emotional problems. Mary’s baseline scores consisted of a full scale IQ of 100 and standard scores of 100 on each achievement subtest. Now assume that Mary suffered an acute onset affective disorder characterized by extreme social isolation, dysphoria, flagging energy, declining appetite, and—most important to the current discussion—halting accumulation of academic skills. Three-months after onset of Mary’s emotional problems, an ED evaluation could readily establish the presence of ED characteristic D (a general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression, one of the characteristics seen in Table 10.2). This was accomplished with interviews, observations, plus broadband and narrowband rating scales). Similarly, it was simple to document that the problem existed to a marked degree (e.g., using the same assessment procedures). Three months’ duration might be considered sufficient to satisfy the ED duration requirement (i.e., for a long period of time). But what about the ED requirement of adverse impact on educational performance?

Let’s start by assuming that Mary did not lose any academic skills. But what if her previously unremarkable academic skill development came to a sudden halt? As Wodrich, Stobo and Trca (1998) showed, an 8-year-old whose previously average academic skill development ceased completely would need to wait between 16 and 24 months before her achievement test scores would become discrepant from her average full scale IQ. Worse, a 12-year-old with suspended academic skill acquisition would have to wait between 36 and 60 months before the appearance of an ability/achievement discrepant from her IQ score. Even worse, a 15-year-old with average IQ and frozen skill development would never produce achievement test scores discrepant from her IQ. Clearly the singular reliance on an ability/achievement discrepancy would prove decidedly unfair to some children in need of ED designation. There has be more than one way to document ED-related adverse impact. Practically, this consideration is important because acute onset characterizes some mental health conditions (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, body dysmorphology disorder). Rigid requirements for low achievement test scores are likely to create mounting insensitivity (the rate of true positives would suffer). Thus, Wodrich et al. suggested that using report card marks, scores on high stakes tests, or criterion referenced academic measures would create better sensitivity for Mary and students like her. According to this approach, Mary was concluded to meet each of the ED eligibility requirements. The final requirement, educational impact, was established by evidence of failure to continue to master the curriculum.

A third type of case, an absence student, is also indicative of adverse effect on educational performance. This is true regardless of the academic skills that might be possessed. Consider the case of Robert, a seventh-grade student with a favorable history of grades and acceptable high stakes achievement test scores. These facts notwithstanding, Robert was always viewed by his teachers as nervous, high-strung, intense, and shy. A crisis arose with a mandatory oral book report. The night before his scheduled report, Robert complained of overwhelming fear, feelings of nausea, shortness of breath, and numbness in hands and feet. Health problems were ruled out; a panic attack was confirmed. Unfortunately, Robert refused to return to school. This persisted even with various informal attempts to bring him back to campus. He was eventually dropped from the school register for excessive absences. Then his parents requested an evaluation under IDEAs Child Find proviso. The school psychologist (and her MDT team) confirmed ED characteristic E (a tendency to develop physical symptoms or fears associated with personal or school problems, as seen in Table 10.2). They also judged the symptoms (in their chronic, pre-crisis form) to have been longstanding and present to a marked degree. But what about adverse effect on performance? Wodrich et al. (1998) point out that even though Robert has neither low achievement test scores nor failure to master the curriculum he nonetheless suffers impacted educational performance. He was no longer participating in schooling. In some ways, this constitutes the most severe form of adverse impact on performance. In light of these facts, and following careful consideration, Robert’s MDT ultimately verified his eligibility for ED services.

There is a key point here. Adverse impact on educational performance is one thing regarding SLD and another thing regarding ED. Skill deficits fit with SLD, but many and varied manifestations of adverse impact are to be expected in cases of potential ED.

The Bewildering “Social Maladjustment” Clause

Read the following and see if it makes sense to you: “The term [emotional disturbance] does not apply to children who are socially maladjusted, unless it is determined that they have an emotional disturbance under paragraph (c)(4)(i) of this section. This muddled phrasing, embedded in the larger IDEA ED definition, represents the famous (infamous) social maladjustment clause. But it is hard to know for sure what its anonymous authors, writing nearly 50 years ago, meant to say. Your interpretation, however, matters. Read one way, and the door to special education services might be slammed shut for many potentially-eligible students (i.e., those with externalizing behavior that brings them into conflict with authority). Specifically at issue are students with Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder. This position was championed especially by attorney Jane Slenkovich, whose writings and workshops for school psychologists and educators proved influential in prior decades. Here is her blunt assertion, “students with social maladjustment are expressly excluded from the definition of SED [Emotional Disability]” (Slenkovich, 1992, p. 22). By the way, this attorney reveals just what type of conduct might keep a student out of special education, it’s…“conduct-disordered behavior (cutting class, lots of sex, drugs, abusive language, etc.)” (Slenkovich, 1992, p.21). Critically, however, if the social maladjustment clause were read an alternative way, the same door would seem to remain ajar to students who otherwise satisfy criteria for ED, notwithstanding any affinity for sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll. Special education and related services might then follow. Important protections would also ensue. This means, for example, that identified students would enjoy protection from unilateral changes to their educational placement based on conduct problems at school (see Wodrich, 2021 regarding “manifest determination”).

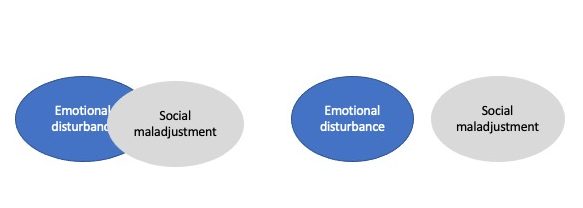

Perhaps the rationale for including the social maladjustment clause was sound back in 1975. There was fear then that special education programs, if rife with ED students, might supersede existing juvenile justice programs. The social maladjustment clause, thus, might have been envisioned as an off ramp to keep hordes of delinquent youth out of the special education system. Whatever the motives behind adding the social maladjustment wording years ago, it has a contentious and confusing subsequent history (Skiba & Grizzle, 2019). A host of problems surround the distinction and its application. Some authors, for example, write as if there are two discrete entities: (1.) ED and (2.) social maladjustment. Logically then, school psychologists’ (and MDTs’) task is to determine if a student has one condition (i.e., ED) or the other (i.e., social maladjustment), or neither. Figure 10.1 depicts these two views. But there are many problems inherent in the proposed ED vs. social maladjustment distinction and its actual application in schools.

First, social maladjustment has no definition within the law, and it lacks a consensus definition outside the law. Logically then, how is it possible to locate students with a condition devoid of a definition? Second, when the lens of logic is focused on the notion of social maladjustment, several commonsense problems crop up. In other words, assumptions about social maladjustment hold up poorly when exposed to the light of day. Olympia and colleagues (2004) listed seven underlying assumptions. Then, one by one, they refuted each:

- Social maladjustment is equivalent to the diagnostic categories of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder.

- Students with social maladjustment act via a conscious decision-making process whereas students with ED act without foresight.

- Students with social maladjustment understand the consequences of their action, whereas students with ED do not.

- Students with social maladjustment have the ability to control their behavior, whereas students with ED do not.

- Students with social maladjustment experience no guilt or remorse.

- Students with social maladjustment are characterized by externalizing problems, whereas those with ED are characterized by internalizing problems.

- Students with social maladjustment are “nondisabled,” whereas those with ED are “disabled.”

There is a third problem with the ED vs. social maladjustment distinction. Practical efforts to discriminate the two don’t seem to work. Costenbader and Buntaine (1999) used a test crafted to separate students (age 12 to 15 years) into ED and social maladjustment groups. In other words, they used a test that envisioned ED and social maladjustment as two distinct entities, like the right image in Figure 10.1. Despite its intent to distinguish the two groups, the Differential Test of Conduct and Emotional Problems; Emotional and Behavior Problem Scale failed to result in “separate, distinguishable behavioral syndromes.” In fact, the true positive rate for students with ED was a mere 21%. Furthermore, this specially designed test miscategorized 14% of students with social maladjustment as having ED. If a test comprised of items expressly designed to distinguish ED and social maladjustment fails to do so, how plausible is it to assume that the less structured judgments of individual school psychologists or MDTs would fare any better?

Fourth, there may be no genuine problem. Instead, everyone merely needs to read more carefully. Consider the simple wording found in the State of Connecticut’s (1997) guidelines about how to interpret ED’s definition: “this definition requires that educators identify as eligible for special education under IDEA only those students with emotionally based disturbance rather than just a social maladjustment” (p. 5). In other words, the task is to satisfy the elements of the ED definition while making sure not to inadvertently include students with just social maladjustment (who fail to meet ED criteria). Much the same was said by McConaughy and Ritter (2008). They too suggest that MDTs concentrate on the ED criteria’s required elements. If these criteria are met, then the student qualifies: “Once ED criteria are met, any evidence of social maladjustment is irrelevant for purposes of determining eligibility for special education” (p. 710). Cloth and colleagues (2014, p. 222) appear to echo this position, “If one reads the clause carefully, … if they [students] meet criteria for ED, it does not matter whether they meet any definition of SM or not.” Now look again at Figure 10.1’s two depictions of ED and social maladjustment. Both ED and social maladjustment (whatever that term might mean) can coexist in the same student. Social maladjustment would seem to be no reasonable grounds for excluding students from services once they meet ED criteria.

For all ED Identifications, Use a Checklist

As you have seen, ED confirmations involve simultaneous consideration of several distinct requirements. Some are simple, others are complex, and still others are annoyingly confusing. Regardless of their nature, all need to be considered judiciously, deliberately, and thoroughly. This is just the kind of situation that invites unwanted errors of decision making—the array of mistakes you read about in Chapter 2. And rest assured that various mistakes can indeed arise during ED decisions. As a case in point, you might want read the interesting work by Della Toffalo and Pedersen (2005). It showed how the presence of something as simple as an outside professional’s DSM diagnosis can supersede objective and case-relevant facts. An antidote is a simple checklist, just as you learned in Chapter 2 (Kahneman, 2011; Watkins, 2009). Figure 10.2 is one example. Your instructor can provide you copies, or you can make your own. Consider using something like this in every prospective ED case.

School Psychologists, IEPs, and Related Services

Even when wearing the gatekeeper hat school psychologists can help guide treatment. Every ED-eligible student must have her own Individualized Education Program (IEP). The IEP will help assure that each student receives a free appropriate public education (FAPE). In cases of ED, who is better prepared than a school psychologist to speak intelligently to FAPE and the proper elements in an IEP? Arguably no one. Given all of the information collected during assessment, is this student best placed in a restrictive setting such as a self-contained highly structured classroom? Alternatively, might she best remain in the educational mainstream with an individualized behavioral program, plus academic supports? Will direct academic instruction, such as from a resource teacher, be required? If the student is depressed (or oppositional and non-compliant), what special instructional considerations might be advised? Are there evidence-based programs that fit the student’s needs. These are all questions suitable for school psychologists. You will see more about matching students and fixed interventions in Chapter 15.

Some students need “related services” as the cornerstone of their IEP. IDEA defines related services broadly. The definition encompasses much that is potentially relevant to school psychologists after their gatekeeping role is completed. “Related services means transportation and such developmental, corrective, and other supportive services as are required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education, and includes speech-language pathology and audiology services, interpreting services, psychological services [further defined below], physical and occupational therapy, recreation, including therapeutic recreation, early identification and assessment of disabilities in children, counseling services, including rehabilitation counseling, orientation and mobility services, and medical services for diagnostic or evaluation purposes. Related services also include school health services and school nurse services, social work services in schools, and parent counseling and training.” [underline added] https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.34

Particularly relevant to the practice of school psychologists is the scope of psychological services, which are indicated below.

“Psychological services includes:

- Administering psychological and educational tests, and other assessment procedures;

- Interpreting assessment results;

- Obtaining, integrating, and interpreting information about child behavior and conditions relating to learning;

- Consulting with other staff members in planning school programs to meet the special educational needs of children as indicated by psychological tests, interviews, direct observation, and behavioral evaluations;

- Planning and managing a program of psychological services, including psychological counseling for children and parents; and

- Assisting in developing positive behavioral intervention strategies.” [underline added] https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.34

In this passage several elements are highlighted (underlined) because of their relevance to the discussion that follows. Consider the case of a high school student named Eloise. She was diagnosed by a psychiatrist with bipolar disorder and started on mood stabilizing medication. Later, outpatient psychotherapy was started. When her grades began to slip, she was identified as ED eligible. But her erratic behavior proved perplexing to her teachers, some of whom threaten to drop her from class because of missed assignments. Looking at the federal definition’s list of related services, Eloise’s MDT and her parents recommended a plan to have the school psychologist, the campus-based professional most knowledgeable about bipolar disorder, “consulting with other staff members.” This would seem to fit the definition of “related services,” as the underlined text above indicates. Moreover, because Eloise’s symptoms wax and wane in severity and character, routine (not just one-shot) consultation was deemed necessary to assure a FAPE was provided. The MDT also recommended on-site, emergency counseling when needed. This might be used during a crisis or when Eloise confronts a particularly anger-engendering school situation. One of the high school counselors was tabbed to provide “counseling,” as a related service. This represented a potential problem, however. Eloise already had an outpatient psychotherapist. Once again, the MDT recommended that the school psychologist liaison with the off-campus psychotherapist, school counselor, as well as Eloise’s treating psychiatrist. Liaison with the professional prescribing medication was deemed especially important “to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education.” This was because frequent medication adjustments characterize Eloise’s treatment, and these were often prompted by second-hand reports from parents about Eloise’s current status at school. A school psychologist-psychiatrist conduit was judged to be a much more effective means of communication. This latter set of responsibilities was considered an aspect of related services under the broad definition of “planning and managing a program of psychological services,” as contained in the federal definition of a “related” psychological service.

Section 504

Section 504 of the Americans with Disabilities Act is now commonly used in schools. Its educational application is designed to prevent discrimination against students with disabilities. According to the U.S. Office of Civil Rights, Section 504 covers students who:

- (1) have a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities;

- (2) have a record of such an impairment;

- (3) be regarded as having such an impairment. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/504faq.html

Section 504 defines major life activities quite broadly. Critical to the current discussion, this includes educational considerations like speaking, learning, reading, concentrating, thinking, and communicating. There is no exhaustive list, so local MDTs have latitude. For example, it is asserted that Section 504 includes students with reading problems not otherwise identified under IDEA (see Brady, 2004). If reading problems not captured by IDEA’s SLD definition are 504 eligible, might those with emotional problems not captured by IDEA’s ED definition be similarly 504 eligible? The answer is probably affirmative. In other words, students meeting DSM-5 criteria likely meet the 504 definition above (regardless of whether they meet ED criteria). In fact, a careful reading of the 2016 Dear Colleague Letter concerning ADHD (found in addressed in Chapter 12) implies just this.

Practically speaking, there is a group of students with 504 Plans but not IDEA-related IEPs. These are sometimes called “504-only students” (Zirkel & Weathers, 2016). A recent national survey found about 1.5% rate of 504-only students. Perhaps it is no surprise that these 504-only students campus wide are disproportionally found in higher income and predominately White schools. The reasons for underutilization of 504 by Black and Hispanic students is probably complex, with racial, cultural, and poverty factors involved. Social justice is also a consideration (Zirkel & Weathers, 2016). As seen below, parents rather than school professionals are often instrumental in the acquisition of Section 504 designations. This means that more financially well off and system-knowledgeable parents may disproportionally advocate for their children to received 504 plans. Most notorious are parents who secure Section 504 plans for their high school-age offspring in order to gain relaxed time requirements for college entrance examinations.

Objectively, Section 504 evaluation processes parallel those for special education. Like for IDEA, LEAs are obliged to identify students with disabilities. Unlike for special education, however, school psychologists seem less intimately involved in Section 504 determinations. In fact, in some school districts, specially designated 504 coordinators are used exclusively. This may be a social worker, counselor or even a paraprofessional. Consequently, in many school districts the processing of Section 504 plans depends on parents bringing an outside document and seeking a 504 plan for their child. As seen in Chapter 12 (regarding ADHD), however, the onus for identification is inappropriately placed on parents. LEAs, not parents, are obligated to locate and protect the civil rights of their students.

There also seems to be confusion about the scope of services rendered under Section 504. You may have heard this said, “This student just needs an accommodation plan, not an IEP.” Technically, students with IDEA and Section 504 eligibility merit indistinguishable guarantees of FAPE. Although this is not always understood, students with 504 Plans can receives services in regular or special education classroom; they may have IEPs or accommodation plans configured in other ways (depending on what the LEA prefers). This is true regardless of the type of disability or its severity. You will hear much more about this topic, including from authoritative sources within the Office of Civil Rights, in Chapter 12 when the topic of serving students with ADHD is addressed.

What about Section 504 plans in actual practice? Research suggests that it is not the type but rather the amount of services that often distinguish Section 504 accommodations from special educational services (Spiel, Evans & Langberg, 2014). This is what was discovered among a group of 97 middle school students with ADHD distributed across 9 schools. When student’s actual plans, both Section 504 and special education-related IEP, were scrutinized, the following services were found to have been provided:

- Extended time (e.g., quizzes, projects)

- Small group instruction

- Prompting (to keep on task)

- Test aids (e.g., allow use of a calculator)

- Read-aloud (to self or another reads for the student)

- Breaks (more frequent than for classmates)

- Study support (e.g., guided worksheets)

- Reduction (number or length of assignments)

- Behavior modification plans

- One-on-one (pull out for 1:1 instruction)

- Modeling skills (model target skills or concepts)

- Preferential seating

- Material organization

- Planner organization (increase student’s temporal organization)

- Adapted grading

- Copy of notes

- Divided tasks (decompose tasks into component parts)

- Parent-teacher contact (increase home-school communication)

Positively, at least one student with an IDEA designation and at least one with a Section 504 designation was receiving each of the services listed above (except modeling skills occurred in no Section 504 plans). The difference was that IDEA-eligible students were promised to receive more items on the list as well as more of the items that required teacher time to implement. “Thus, school psychologists and school-based teams may be making decisions about….an [IDEA-related] IEP or a 504 Plan based upon the amount of services required to meet the student’s needs rather than the type of services that may be required to meet the student’s needs” (Spiel, Evans & Langberg, 2014, p. 261). Even though FAPE is called for regarding both IDEA and Section 504, the former seems used to give students more intensive services, at least in this one study.

As with IDEA-related identifications, Section 504 determinations are best accomplished by following a checklist. Unlike IDEA categories (e.g., ED), however, the school psychologist is only rarely the LEA’s lead professional for identification. For example, many 504 plans involve health-related disabilities. Consequently, school nurses may take the lead in devising checklists to identify students. At other times, as stated above, 504 plans are handled as if purely administrative (without routine school psychologist involvement).

Unfortunately, when social-emotional elements are present, excluding the school psychologist from planning is a potential problem. This is for the same reasons stated regarding development of IEPs. What’s more, if they hope to fulfill their ethical commitment to improve the quality of students’ lives (NASP, 2020) and if they aspire to extend their role into the mental health domain, school psychologists’ self-advocacy for participation in 504 plans seems worth considering. Even when tasks are mostly administrative, school psychologists may sometimes push for permission to don their clinician’s hat.

Summary

School psychologists sometimes act on behalf of their employers in quasi-administrative capacities. This is because LEAs are required to identify all students with a disability defined in IDEA. By virtue of their background and training school psychologists are especially adept at helping identify students with ED. Indeed, their ability to review records, observe, interview, and apply sophisticated rating scales is unmatched by other school professionals. When these techniques are paired with school psychologists’ knowledge of the diagnostic process (e.g., the importance of base rate, the reliability and validity of their techniques) they can help faithfully identify students. Moreover, their knowledge of psychopathology, school systems, and intervention techniques enables school psychologists to contribute to planning. This is true whether students are identified for services via educational (i.e., IDEA) or civil rights (i.e., Section 504) laws