13 How to Prepare Oral Reports

Key takeaways for this chapter…

- School psychologists have an ethical obligation to share assessment results, which is often done orally

- Regarding parents, results are routinely shared during an oral feedback session that might occur simultaneous with, or independent of, a specialized eligibility team meeting

- Oral reporting, such as at an IEP meeting, is most effective if it follows a plan, is sensitive to attendees’ knowledge level and their emotional needs, and adheres to an established timeline

- Because there are many types of referral questions, a single approach to oral feedback sessions is impossible

- Checklists, viewed before an oral session and completed after it, can help with skill development

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- Zach, illustrating the bottom-up and top-down approaches

- Josh, direct student feedback

- Constance, direct student feedback

- Jamal, direct student feedback

Among school psychologists’ most important tasks is conveying assessment findings. In large part, school psychologists make their living by way of communication, including communication of assessment findings. It’s sometimes easy to forget the obvious. School psychologists do not manufacture a product like an industrial worker, they do not systematically engender reading or math skills in pupils like a teacher, they do not avert or correct illness like a healthcare worker, and they do not devise plans to build something valuable like an engineer. Instead, they often size up and make sense out of students’ problems. This is an important undertaking because it assists teachers and parents in understanding, supporting, and correcting difficulties. Meaningful assistance happens, however, only with clear communication.

There are also unavoidable obligations when students are assessed. At the conclusion of the process, school psychologists are obligated to share findings with parents. This is true regarding ethical guidance from both NASP and APA. According to NASP Principles of Professional Ethics (2020) Standard II.3.11 “School psychologists adequately interpret findings and present results in clear terms. They ensure that recipients understand assessment results so they can make informed choices.” Similarly, according to the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (APA, 2016). 9.09 “Psychologists retain responsibility for the appropriate application, interpretation, and use of assessment instruments, whether they score and interpret such tests themselves or use automated or other services.” The same Principles in section 9.10 indicate that “…. psychologists take reasonable steps to ensure that explanations of results are given to the individual or designated representative….”

Verbal feedback satisfies these ethical requirements. But if there is a written report (which almost always exists) parents will also be able to access it. Broadly speaking, the two principal vehicles for communication are orally and in writing. We cover post-assessment oral communication in this chapter. Preparation of written reports is covered in the next (Chapter 14).

The Parent only Feedback Session

There are several ways in which oral feedback can happen. Let’s start by looking at the simplest variant, the feedback session. In its standard form, as routinely practiced by clinical psychologists, neuropsychologists, and counseling psychologists, it involves sharing information directly with parents (and potentially the student). A typical scenario involves a child with a potential social-emotional problem seen in a clinic or private office. As you learned in Chapter 3, a referral question would have been mutually agreed upon before assessment commences. Logically then, that same referral question is unequivocally answered during a face-to-face feedback session. In other words, the assessment process is launched by a question and wrapped up with (oral) answers to that very question. Although this sounds simple, often it is not.

These feedback sessions are inherently complicated and fraught with potential missteps. There are many considerations for post-assessment sessions as practiced in clinics (and sometimes) in schools. Regarding potential problems and ways to avoid them, Tharinger and colleagues (2008) presented detailed considerations that they gleaned from the professional literature. Happily, these comprise a list of ideas psychologists might keep in mind to enable an ethical and effective feedback session. Included are the following:

- restate the purpose for assessment at the outset of the feedback session

- convey only the most pertinent assessment findings

- balance unpleasant findings with information about the child’s strengths

- speak in clear, common language (not jargon, not with too many numbers)

- be concise

- adapt to parents’ cognitive level

- attend to parents’ mental health

- attend to potential parental feelings of guilt and responsibility

- avoid recommendations that may prove too demanding of parents

- evaluate the parents’ understanding during the session

Others have referenced similar themes, including encouraging parents to openly voice their own concerns and to freely pose questions (Pruett, 2013). Similarly, parents often want to hear a review of the assessment process and hope that diagnosticians recognize that an assessment of their son or daughter often comes with an emotional reaction (and an accompanying need for support). This is apt to be particularly true when a diagnosis like autism is made (Abbott, Bernard & Forge, 2012).

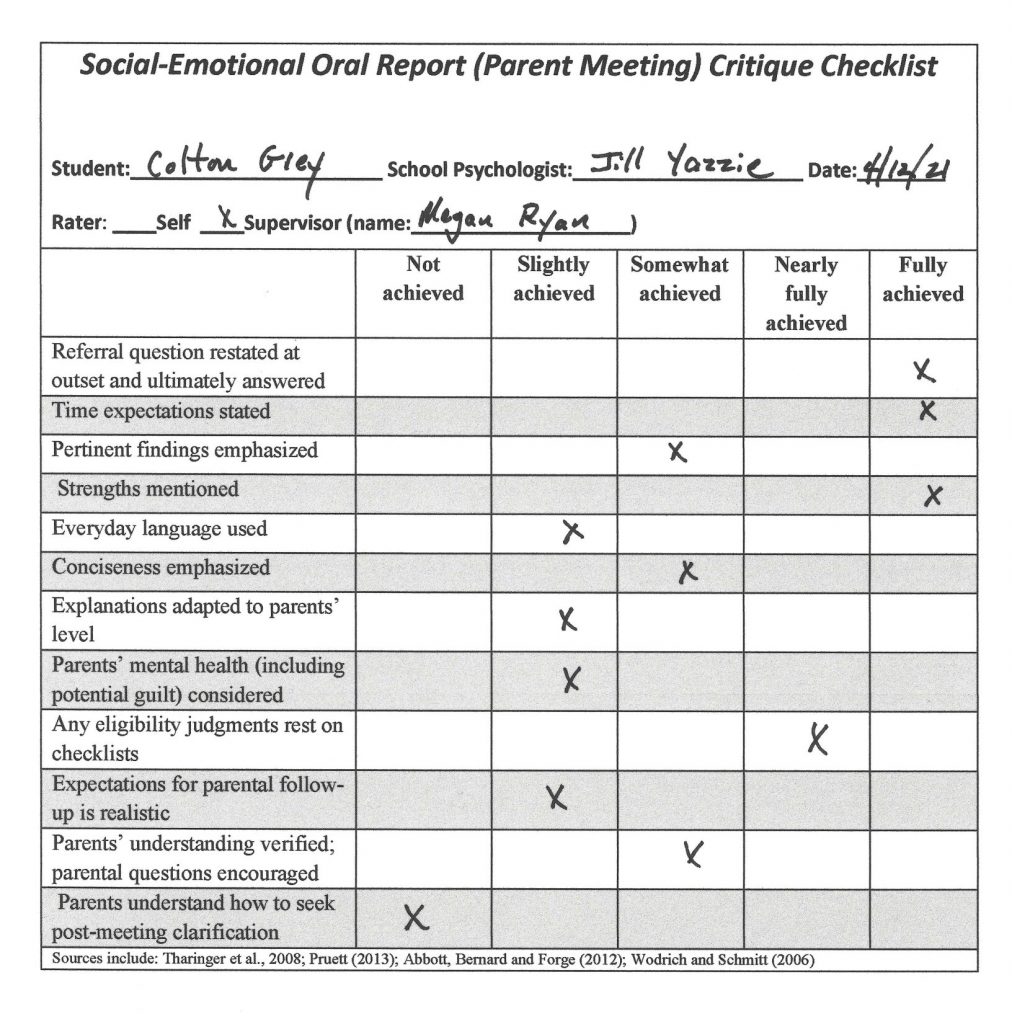

It is easy to see that parental feedback is not only important, its delivery is also daunting. Consequently, novice psychologists often feel anxious about their capabilities and uncertain about how to proceed. These are skills that are hard to learn. Some of the barriers to learning might arise from the nature of feedback sessions themselves—executed in private and without a detailed, reviewable record. In other words, psychologists meet with parents face-to-face, provide feedback, and then go on to the next case. Consequently, their precise words and even their preferred style is rarely available for colleagues to critique. Equally constraining, one psychologist has no access to what other psychologists do during their feedback sessions. In some ways, they are flying blind. Contrast oral reporting with written reporting. In reality, most practicing psychologists have read many, many of their colleagues’ written reports. The relatively public nature of written documents permits school psychologists to mirror others’ writing style, replicate their format and parallel their insights. If you are a student, your supervisor may sit in on one or two feedback sessions before you are on your own. This is too little guidance to advance the skills needed for a good feedback session. As you will see in Figure 13.1, a checklist created from some of the points raised above may assist you in bending the arc of your oral skill development in an upward direction.

But when might school psychologists conduct feedback sessions akin to those of a clinic-based counterpart? For some school psychologists, such as those restricted to a gatekeeping role, the answer may be quite rarely (or even never). For others, such as those who engage mental health questions and provide mental health services rather than just gatekeeping, the answer may be somewhat frequently. Returning again to Table 3.1, referral questions #1, 2, 7, and 8 might involve traditional post-assessment feedback sessions. In contrast, other referral questions, such as those that involve special education eligibility (i.e., #10-13), may not.

The Parent only Feedback Session as a Prelude to a Full Eligibility Meeting

Often, of course, school psychologists’ referral questions concern special education eligibility or Section 504 entitlement (referral questions #10-13 in Table 3.1). Many times, but not always, there is a single on-campus eligibility meeting encompassing assorted individuals, not just one psychologist, sharing assessment information with parents. Because this meeting is charged with establishing formal eligibility it is inherently different than a clinic-style feedback session. It is quasi-legal, and it concerns satisfying eligibility criteria (as covered extensively in Chapter 10). The trouble is that parents may need to be told sensitive assessment results and confronted with potentially disquieting conclusions during a rather public meeting. School psychologists often have a lot of information to convey during a team eligibility meeting. The same might be true of other diagnosticians (e.g., occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists).

Thus, some school psychologists conclude that there is simply too much psychological information to share during a compressed eligibility meeting. Furthermore, some school psychologists anticipate that touchy subjects will arise, and these will prove too sensitive to handle adequately with a large group present. Consequently, some school psychologists schedule pre-team eligibility meetings during which only parents are present. Under these circumstances, the school psychologist later attends a formal eligibility meeting with her professional colleagues and the student’s parents. Envision a situation, for example, where assessment findings point toward autism or intellectual disability (ID). The volume of information shared to confirm eligibility for either autism or ID, coupled with the delicate nature of this information, prompts many school psychologists toward a preliminary meeting. In fact, researchers found that approximately three-quarters of school psychologists would hold a one-on-one preliminary meeting (i.e., about the presence of a developmental disability) in advance of a group meeting (Wodrich, Tarbox, Balles & Gorin, 2010). This same practice might also be true of various social-emotional assessment findings. For example, a situation with the same need for a “pre-meeting” might concern a student with severe OCD who is ultimately destined for ED designation.

What is the nature of a parent-only feedback meeting? Although variability is likely common, a meeting like this might represent a hybrid of the traditional, clinic-based approach covered above and the quasi-legal, eligibility determination meeting described in the next section below. The points made by Tharinger and colleagues likely still apply, but rules for special education eligibility warrant attention (as do programming options if eligibility is later established formally). Many school psychologists seem to learn that a preliminary meeting allows them latitude lacking in a team eligibility meeting. This is particularly true for parents who are easily confused, those that require convincing, or those that seek details. For these parents, a so-called “bottom-up” explanatory approach might be advisable (see Wodrich & Schmitt, 2006).

The bottom-up approach comprises feedback presented one detail at a time. It involves a presentation characterized by: fact, fact, fact, fact, finally followed by a fact-congruent conclusion. This approach allows a central conclusion (e.g., a particular diagnosis, a special explanation for a presenting problem) to become progressively clearer so that it is ultimately grasped and accepted as credible. Correspondingly, the bottom-up approach represents an antidote to prospective parental confusion on the one hand and parental disagreement on the other hand. In other words, when parents are confused about the nature of your assessment process or doubt your conscientiousness, thoroughness or impartiality, then your findings are in jeopardy. The rationale is that the bottom-up approach often solves these problems. Its essence is details presented patiently and clearly. This approach helps parents understand the psychologists’ assessment process; it coincidentally teaches them about the nature of the diagnosis or explanation under consideration. The school psychologist checks at each stage to make sure parents understand. Typically, bottom-up explanations concern a discrete diagnosis (e.g., like Breanna’s depression in Chapter 7). Although sometimes well suited to parents’ needs, the bottom-up approach is generally too tedious, too time consuming, and too psychologically-focused for the type of group (team) meetings that concern special education eligibility. Illustration 13.1 demonstrates the bottom-up approach as it unspools when parents of an elementary student named Zach Long meet alone with a school psychologist to hear about their son’s possible ADHD. This meeting, as we will soon see, can occur when special education issues are destined to be discussed in a later meeting. Incidentally, Zach’s case could realistically occur in a state like Arizona, which now authorizes certified school psychologist to confirm the presence of ADHD when OHI services are at issue. As you read Illustration 13.1, you might ask yourself how well the bottom-up approach might work if this were a meeting with an entire team, not just Zach’s parents.

Of course, there is a counterpart and contrasting approach that has been entitled the top-down approach (Wodrich & Schmitt, 2006). As seen in Illustration 13.2, illustrative of the top-down approach Zach’s parents receive the big picture first, followed by some details coupled with plenty of time for clarification and planning. As you might suspect, in reality, most meetings reflect their own unique blend of bottom-up and top-down elements. That said, it is helpful to contemplate the best style that would match the particulars of each meeting you conduct. Sometimes school psychologists (provided they are versed in both contrasting approaches) even offer parents the choice of styles at the outset of parent-only feedback sessions. Accordingly, a school psychologist might say something like this: “As you know, we are meeting to talk about your daughter’s evaluation results. I want to be responsive to your needs. There are a couple options for you to consider. First option: I can offer you the big picture followed by details that led me to my conclusions. A second option is more or less the opposite approach. I could offer you details of the assessment and things like scores, one at a time. At the end, I would give you my conclusion and recommendations. Either way, we’ll save time at the end of our hour together to talk things over, for me to answer questions, and for us to discuss what this all means.” A warning, especially to beginning school psychologists, is in order. If you offer parents options, be certain in advance that you can live with either style that they might select.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’m glad we can meet this morning. I know it’s inconvenient to come in early, but I wanted to share this information with you personally. As you know, we all meet as a group next week.

FATHER: I think it’s a good idea.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Just to be clear, we have about an hour. In my experience, I can go through my material with you point by point in an hour. Please interrupt if you have questions. We’ll have time to talk at the end, also. Does that sound okay?

FATHER: Works for me.

MOTHER: Yes, thanks.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Just to be clear, today is a chance for me to share my findings. As you know, I collected a lot of information about Zach. But this is not an eligibility meeting. That happens in a group next week. But today I want to share what I found so that the additional information next week makes sense. We’ll hear from his teacher and the nurse at that point.

MOTHER: Yes. I understand this. Does that mean next week we’ll talk about OHI?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes. But OHI is determined by the team. As a school psychologist, I can give input about ADHD, but the team must decide eligibility, including OHI eligibility. As you remember, OHI was the question that got the process started.

MOTHER: I think this is what we talked about during the first meeting, correct?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes, that’s right. I know that you had suspicion about ADHD.

FATHER: Yeah, but I also had doubt. There’s a lot of kids being diagnosed with that condition. There’s a lot of medication. Some of this is just boys being boys.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well, I would like to share my information with you and see if we come up with a reasonable conclusion about ADHD because that’s the big question. If it’s okay with you, I would like to give you details and let you see how we go about figuring out if ADHD is present or not. Okay?

FATHER: Absolutely.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Our goal is to be thorough and logical. We don’t want to over-identify and we don’t want to under-identify. That’s why we use an entire process. We don’t count on impressions.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: We start the process by asking how common is ADHD. Large research studies say about 6% of elementary students in general. But we know that the percentages are much higher with kids who are referred. In our setting, about one in five elementary students referred for evaluation has ADHD. This helps us know it’s pretty common but it’s also not every student we evaluate.

MOTHER: Makes sense.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Our next step is to look at health and development. I read Zach’s folder at the nurse’s office. I also read, page by page, the 11-page History & Development Questionnaire you completed for us as part of the evaluation process. It’s this one (she shows parent the actual form).

I couldn’t find information about health problems that would cause him trouble in the classroom. For example, there is no diabetes or epilepsy or anything like that. Plus, Zach has had good school attendance. Missed school is not a reasonable explanation for school problems. And he has not had hearing or vision problems. If it was just a hearing or a vision problem, we wouldn’t want to miss that. Correct me if any of these facts are wrong.

MOTHER: No, you are correct.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: One important thing you did share on your History & Development Questionnaire is that several cousins have already been diagnosed with ADHD. We know that ADHD is caused by genes. When biological relatives have ADHD, that raises the risk of you having ADHD. Research results tell us that Zach’s risk goes up somewhat based on the information from his cousins.

FATHER: But he doesn’t spend time with the cousins.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Good point. But it’s this, research shows it’s genes not experience. His cousins shared genes with him. This is what bumps up his risk.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: We next had Zach’s classroom teacher complete a very long rating scale. It’s this one (she shows parents a BASC-3 response booklet). You completed the same thing for parents (she shows parents the BASC-3 response booklet that they completed).

FATHER: We debated doing two forms. I was going to photocopy the original. We finally decided that his mom and me would work together. We did just one.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Good. We’ll go through that in just a minute. But first let’s look at his teacher’s ratings. Here’s the logic for the rating scale. There’s lots and lots of questions. Some of them cover mood, some of them cover behavior, some of them cover attention, some cover other specific problems. The teacher bubbles-in her answers to each question. We put her answers in a computer program. The computer groups her answers into scales. The scale measures just one thing, like anxiety or attention. This allows Zach’s individual ratings to be compared to teachers’ ratings with hundreds of elementary students. This lets us see if high scores turn up on any of the scales. If high scores are present, we want to see where they are. This is a fair and objective way to do things. Might there be any questions that I can answer?

FATHER: So, will we see the teacher ratings?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes. I will show you Zach’s scores on each one of them. In fact, let’s look at this printout (shows BASC-3 printout page with figure entitled “Clinical and Adaptive T-score Profile). See the dots? Those are the many points at which Zach’s scores appear. Again, this is based on his teacher’s ratings. The lines connecting them are not especially important. As the dots move into the light gray area there are potential problems. Dots into the dark gray area mean greater risk of problems. You can see right away some scores are in the gray area. This, for starters, tells us the overall teacher rating looks more like a student with a significant problem than a student without a problem (points to Behavior Symptoms Index). That score is clearly in the dark gray area. So, do some of the others, which we will look at closer in just a minute. Okay so far?

MOTHER: Yes, we’re fine.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Let’s work left to right (she places a pencil tip on each dot as she speaks). The first scale is Hyperactivity. You can see it’s in the darker gray area. This means the teacher checked many more items than average about restlessness, out of seat, interrupting, and acting without thinking. The next scale, Aggression, is a little bit elevated. But it does not fall into the gray. The one after that, Conduct Problem, is back in the gray area. This concerns following rules, cooperating, and not causing a management problem. Again, Zach’s teacher is rating this as a problem.

FATHER: So, this just says that the teacher sees him as hyper and causing trouble.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes, but she does not get to offer just her overall opinion. She must consider and mark one question at a time. Each item is on a continuum from “never happens” to “happens almost always.” We assume she answers honestly. In fact, the scales designed to catch problems with exaggerating or minimizing problems do not have red flags.

FATHER: Okay. I do think she is honest.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Because hyperactivity and conduct problems are both elevated the next score (points to Externalizing Problems in the printout) is also elevated. But it doesn’t tell us anything new.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: We don’t want to think just about ADHD. It’s a popular explanation. Everyone has heard about it. There’s a risk that that could be our pet explanation. The good thing about this system (points to printout) is Zach gets ratings on lots of potential problems. The next three are Anxiety, Depression, and Somatization (points to dots on the profile). We were not thinking any of these were true of Zach beforehand. But it could be. The teacher ratings say no, probably not, for all three of these. By the way, these three go together because they’re often experienced by a child but not seen by observers. Kids can worry, feel sad, or have concern about their body (somatic concerns) and nobody else knows. Fortunately, this does not appear to be the case with Zach.

MOTHER: This makes sense to me; he’s basically a happy kid.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Now let’s look at the next three (she directs parents back to the BASC-3 printout). One of these is in the gray area. Let’s look down and see what it concerns. It turns out to concern Attention Problems. This is inattention, distractibility, forgetfulness, and disorganization. We see this score is in the dark gray area. This elevation points toward a problem as rated by his teacher. But the next two (points with pencil tip), atypical or unusual behavior and being socially withdrawn are not in the gray area.

So, if we ask ourselves which symptoms is Zach’s teacher seeing in the classroom it appears to be two. One is hyperactivity. The other is inattention. She sees a little bit of problem following rules and struggling to cooperate. The rest of her ratings here (the school psychologist points across the entire array of clinical scales in the printout) are not elevated.

MOTHER: This seems to fit with what we were thinking, right?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: This only adds a little bit of new information but so far, yes.

The other scales to the right here (the school psychologist points to adaptive score profile on the right of the printout page) concerned adapting, functioning effectively, and getting along with others. Low scores here are problems, not high scores. In some ways, this asks if any of the symptoms seen here (points to the clinical scales in the profile) are causing problems in daily life or with functioning. And you see that social skills, study skills, and functional communication are in the gray area (points with pencil tip). Incidentally, this pattern shows up pretty often. It says that maybe the hyperactivity and inattention are actually causing real-life problems.

FATHER: Having the problem is this (points to adaptive scores in the printout)? How low are these?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well his scores are pretty low. Around the fifth or 6th percentile for these adaptive skills. This means only about one in 20 kids his age would be having this much trouble, at least according to ratings from his classroom teacher.

FATHER: Oh, I see.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Let me summarize so far. We already had some suspicion about ADHD (she pauses for eye contact with each parent). We know that ADHD is pretty common among kids referred for evaluation at our elementary school (she pauses for eye contact). Zach has an elevated risk because ADHD characteristics are in the family (pauses once again for eye contact). And so far, the objective items marked by his teacher seem to match with ADHD (pauses once again for eye contact). This doesn’t prove anything. It just makes it increasingly likely that ADHD is present. I would like to stop for just a second. Do you have any questions for me so far?

MOTHER: So how will we know for sure?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Let’s keep going and I think you’ll see.

[The exact same process is repeated regarding the printout BASC-3 Parent Rating Scale, details are skipped here for the sake of brevity].

LATER IN THE MEETING

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: We have two sets of ratings. One is from home and one from school. They look pretty similar. Both are strongly suggestive of ADHD. So is Zach’s background information. But let’s be thorough.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I next observed Zach twice in his classroom. I used an objective system to get percentages for time paying attention. At 30 points during class Zach gets rated by me as either on task or off task. I have to follow a set of rules for making on-task or off-task ratings. I did the same for some of his classmates, so we’d have a fair comparison about paying attention. The first time I did this, Zach was off task 2½ times the rate of his classmates. The second time, he was off task almost twice as much as his classmates. This doesn’t prove anything, but it’s another piece of information pointing toward ADHD. There is an advantage to this approach. It does not depend on people’s impressions. It’s direct observation of his behavior itself. By the way, during this observation I didn’t really see other problems. Zach didn’t look anxious, he didn’t look depressed, I saw nothing unusual about his behavior. He just didn’t pay attention. By the way, he was very friendly with the other boys in the class. They seemed to like him.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I don’t know whether you guys look on the internet about this stuff or not. But some material on the internet talks about using actual tests for ADHD. Not rating scales but performance tests. One of them is a kind of pay attention test. It’s called the continuous performance test. Some clinics use this and claim it detects ADHD. In our school district we considered using this. But research says it leads to too many over-identifications. It picks out kids as having ADHD who don’t actually have it. It’s also too often under-identifies. It misses kids who actually do have ADHD. We choose not to use this.

MOTHER: Is the TOVA an example of this?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes.

MOTHER: There’s a clinic that uses this. Evaluations costs $1,400. But they say they’re almost 100% accurate in ADHD diagnosis.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Again, we chose not to use it for the reasons I already mentioned.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: To be extremely thorough, we ask both you and his teacher to do a little bit more detailed rating about ADHD. This is the scale here (points to an ADHD-5 Rating Scale completed by parents as well as another one completed by teacher). Let’s take a look. This is actually a rating scale based on the formal diagnosis of ADHD. I see that the two of you, mom and dad, working together checked seven symptoms of Inattention. These are: poor attention to detail, difficulty sustaining attention, fails to listen, poor follow through, loses things, easily distracted, forgetful (the school psychologist pauses for eye contact after each symptom is mentioned). And I see that you two working together checked seven symptoms of Hyperactivity-Impulsivity. These are: restlessness, excessive running and climbing, too loud in leisure activities, on the go, interrupts/intrudes (she again pauses for eye contact after each symptom is mentioned). To be thorough, we had Zach’s teacher complete the same ADHD form. She checked eight symptoms of Inattention: poor attention to detail, difficulty sustaining attention, fails to listen, poor follow through, doesn’t finish school work, poor organization, loses things, easily distracted, plus six symptoms of Hyperactivity-Impulsivity: restlessness, excessive running and climbing, leaves seat too often, on the go, interrupts/intrudes. You also both checked that symptoms of ADHD are causing impairments. In other words, real-world impact. For you, it involves family/teacher relationships, relationships with other kids, and homework. For his teacher, this included family/teacher relations, relationships with classmates, academics, and behavior problems.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Let me pause for questions.

MOTHER: Is the last checklist we did the same as part of the BASC-3 (she points to the printout reviewed earlier)?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Do you mean that the questions are the same?

Mother: Yes.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Good question. No, the last scale has questions that are exactly like the formal requirements for ADHD. The BASC-3 has similar questions but not exactly the same. The reason we use the ADHD-5 Rating Scale is that it helps us see whether were at the point of a formal diagnosis. Also, we know that when either parents or teachers have a high overall rating on the ADHD-5 Rating Scale, it really raises the true probability of having ADHD a lot over not having high ratings. Zach has exactly those high ratings that strongly suggest ADHD.

MOTHER: Looking more and more like ADHD?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Let’s review. The starting concern was suspicion about ADHD. We see a lot of kids at this elementary school for evaluation who have ADHD. Zach’s chances are boosted further because there are biological relatives with ADHD. Objective rating scales completed by his teacher have a pattern that looks like ADHD. That rating also showed probable behavior problems. Your objective rating scales also look like ADHD, also with behavior problems. Behavior problems are quite common among boys with ADHD. Classroom observation done twice showed greater problems with inattention than classmates. And finally, out-of-the-textbook formal requirements for ADHD are met according to his teacher and you, his parents (the school psychologist counts on her finger as each of these points is made; she also pauses for frequent eye contact to assure that parents are following).

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: But ADHD is only present if all of the set of listed requirements are satisfied. That’s what I have listed on this simple checklist. Let’s take a look (she shows parents a checklist with each DSM-5 criterion listed in simple terms). The first question is, Are there symptoms of either Inattention or Hyperactivity-Impulsivity? Yes (she pauses for emphasis and makes eye contact). Did the symptoms show up before age 12? Yes. Are the symptoms causing impairment? Your information and that from his teacher say yes. Are there problems in two or more settings? Again, your information and that from his teacher say yes. A final requirement is that another problem is not mimicking ADHD. In other words, could the problem really be anxiety, depression, something like that? We want to be thorough and make sure this is not the case.

Rating scales seem to say no. Anxiety and depression are not elevated. As you know, I interviewed Zach. When I did so, I could not find other symptoms such as anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, reaction to stress, or similar explanations. Incidentally, he was fun to interview. He has a good sense of humor.

Because all of these boxes are checked off (the school psychologist points to her personal worksheet for confirming the DSM-5 ADHD requirements), it’s my opinion he has ADHD. In fact, if we moved piece by piece through the information every piece seems to raise his ADHD probability. We have a technique to consider probability (the school psychologist had earlier calculated a set of probability nomograms) which would place him above 90%.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Let me stop at this point. I want to make sure you understand all the steps that we went through. I want to make sure that there no questions about the various pieces of information that I failed to make clear. And that you see each piece contributes to a final conclusion. We want to stay away from opinion and snap judgment.

FATHER: That’s a lot. I did not understand how the process works. I agree with your evaluation.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well, this is the psychology style. Not everyone uses this much information.

FATHER: I appreciate what you did for Zach.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: This can be a little unsettling for some parents. They may feel bad about the conclusion.

FATHER: His cousins have ADHD. But, truth told, I might also have ADHD.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Suspicious, not diagnosed?

FATHER: Exactly.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: We hear this a lot. We can talk more about this if you like. I can send you some interesting links if you are curious. [Note the school psychologist will not assess the presence of any ADHD characteristics of Zach’s father; she will merely share links, like those from the National Institutes of Health].

FATHER: Let’s talk later. Maybe after we talk next week about the OHI thing.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’d be happy to do so.

Now you will see a contrasting approach (one that is top-down) in Illustration 13.2. This approach kicks off with a big picture conclusion and then fills in, as needed, with assessment-related details. Note the distribution of time within this meeting and the relatively brief time deployed to explain assessment findings per se.

Illustration 13.2 Top-down Feedback Meeting with the Parents of Zach Long

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’m glad we can meet this morning. I know it’s inconvenient to come in early, but I wanted to share this information with you personally. As you know, we all meet as a group next week.

FATHER: I think it’s a good idea.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Just to be clear, we have about an hour. In my experience, I can share with you my overall conclusion right at the start. Then we’ll have plenty of time to go over as many details as you are interested in hearing. This can include how the assessment was done plus what it means for services. Does that sound okay?

FATHER: Works for me.

MOTHER: Yes, thanks.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Taken together, the information indicates that Zach does have ADHD. When we meet next week, I think the team will conclude that he is eligible for OHI services.

MOTHER: Okay. I’m not at all surprised. This make sense.

FATHER: I have a number of questions about treatment and services. But first I would like to hear about the various things you did in Zach’s case to get to that conclusion. I’m not disagreeing with your professional opinion.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Basically, I followed all the steps necessary for a complete evaluation. I wanted to make sure that Zach actually had ADHD and he did not have some other problem that might mimic ADHD. To be sure, I carefully reviewed his history, questioned his teacher, questioned you both, used general rating scales with both his teacher and with you, observed him twice in his classroom, used specialized ADHD rating scales, and had a chance to interview him. Incidentally, he seemed to enjoy this, and so did I. He has a nice sense of humor. Would you like to hear the names of the rating scales and details about scores?

FATHER: No. Just how they turned out generally.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: In general, the rating scales, both teachers and yours, had a pattern matching ADHD and not really much else (except for the kinds of problems with behavior that often go along with ADHD). In other words, scales that measure hyperactivity and inattention had scores indicating problems. Scales tapping things like anxiety or depression resulted in average range scores. The same big picture was true for the other sources of information, like Zach’s history and my interview with him.

MOTHER: Would you say he has a severe or mild case?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: That’s a good question. In psychology, and especially in schools where we use psychology, severity usually isn’t the way we think about this. Instead, it is how much impact is happening. And, also, how much service is needed.

FATHER: Should we asked his pediatrician about severity?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Sure, if you wish. If you sign a release, I can send a copy of my report to her. But let me go back to my earlier comment. For Zach, there is moderate impact at this point. His record shows that his report card marks are a little below average. More importantly, over time his teachers had said that he often fails to complete work and he can distract classmates who are working.

FATHER: Yes, we know all about this.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: The rating scales that you and his teacher completed can also help answer your question. They also suggest some degree of impact. For example, his teacher’s rating show that compared to elementary students generally, Zach appears to have problems with things social skills and knowing the ways to get along with other, study skills and work completion, as well the way to communicate clearly in everyday life. Would you like to see the printout of his scores on these things?

FATHER: No, I don’t need to see that.

MOTHER: I’m eager to hear about services.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Before we do that, part of my conclusion about ADHD depends on just what you are asking. It’s about true problems based on ADHD symptoms. Regarding life out of school, you both indicated potential problems with relationships and getting homework done.

FATHER: For sure.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: His teacher said he can have trouble sometimes getting along with classmates, academic problems as well as difficulty controlling his behavior. By the way, despite this Zach seems to have many friends in class.

MOTHER: He’s actually pretty funny, but we are concerned about where we go from here. What do you recommend?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Thinking back to your earlier question, let me say this. If there is a moderate level of school impact, which I think there is, then this suggests services will probably be needed. The sort of things that are required for him at school probably can’t be done without an individual plan. The plan, if it is part of special education, can be given with a guarantee. Are you familiar with the term IEP?

MOTHER: Yes.

FATHER: Yes.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: If Zach gets an IEP, it would be created to respond to the ADHD-related impact he is experiencing in school.

FATHER: What form would it take, if we decide to go forward?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Your question is a great one. I need to be careful, however, to not overstep my responsibilities. As I said at the start, I think that the team will conclude that Zach needs an IEP related to OHI. He most likely needs services in the regular classroom with oversight by a resource special education teacher. He may also need to be involved with the school counselor to oversee some of the things I’ll mention in just a minute. Next week, the team will get together with you to consider OHI services. I included a number of recommendations in my written report. You will receive a copy of the report. For now, and remember, exact details, are for the team to determine, I can say this. His needs are probably going to require a classroom behavior plan. Included would be elements like clear behavior targets and fixed consequences, positive and negative, based on behavior.

FATHER: We started doing this at home based on a book from his pediatrician.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: The more that home and school do things the same way, the better. This may be one reason to have his school counselor involved. The counselor might help keep you at home and us here in school on the same page.

MOTHER: That was actually in the book that we got at his pediatrician’s suggestion.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: There are some other suggestions concerning Zach’s classroom that you will see in my report. They involve teaching style and classroom organization. With the help of his counselor he might also benefit from some self-monitoring strategies. Again, these will be included in his report in a general way.

MOTHER: What about details? Does his teacher know how to do these things?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGISTs: You are asking reasonable questions that are best held for next week’s meeting. But I can say this regarding details, I know that the special education department at Zach’s school has prepared very special ways to put some of these educational practices in place for students with ADHD. The details appear in a “how to” type documents that teachers printout for their use. Again, however, some of this rightfully falls in the realm of the educators, not me as the SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST on the team.

MOTHER: Okay.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: A key part of today is to make sure that you understood my conclusions about Zach. It’s also to address any lingering questions. If we take care of these things today, next week’s meeting will have more time for planning.

FATHER: I agree with your conclusions. I don’t have a problem. I think I understand what you did and why you reached your conclusion. But I do have one more question. What about medication? What is your professional opinion? I hear a lot of opinions out there.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I can answer in just a minute, but first I want to say that neither of you seem either confused or especially upset about the conclusion. Am I correct?

FATHER: I may not show it, but I’m probably worse than she is in being bothered by stuff like you just said. I’m not really upset. Maybe it’s harder form me because I suspect I might have ADHD myself. Not diagnosed but I’m suspicious about myself.

[The same discussion found in the bottom-up approach would follow here].

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Back to the Zach-and-medication question. It’s a good question, but it really is a medical question. You might want to talk to his pediatrician. I would say this, personal opinion and personal experience are one thing. Research and facts are often another. I encourage parents who want more information to visit recognized sites. Those are sites based on research and consensus of those who specialize. You will see links in my reports to the U.S. government’s sites at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). These are unbiased sites that are paid for by tax dollars. Each of these contains facts about the treatment you mentioned plus many others.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’ll planning on seeing you at next week’s meeting.

MOTHER: Thanks, I’ll be there but Zach’s dad will have to miss because of work.

The Special Education Team Eligibility Meeting

Some ideas well suited to parent-only meetings (except the bottom-up approach) might also fit group eligibility meetings. But the latter type of meetings have a crucial purpose that is distinct from (or sometimes complementary to) a parent-only feedback conference. This is because team eligibility meetings are necessarily quasi-legal. They are mandated before students access entitled services (or protection from discrimination, in the case of 504 Plans). These considerations are not true of generic feedback meetings. Anyone who doubts the quasi-legal nature of eligibility meetings should consider their extensive paperwork. Associated with eligibility meetings, parents are given advanced notice, they are told about their rights to contest findings, they are required to sign extensive paperwork enrolling a student in services and sanctifying those services in the form of an IEP.

What’s more, these meetings involved several individuals besides the evaluating school psychologist themself (i.e., they are “team” meetings). Minimally, the student’s current teacher, a special educator in the area of potential disability, an administrator, the school psychologist and parent/ guardian attend. When evaluations are conducted by allied professionals (e.g., speech-language pathologist, occupational therapist) the numbers can swell. Add a school nurse if there are prospective health considerations and potentially even an outside advocate if parents anticipate a dispute, and the count grows still further. Under these circumstances, the risk is that team eligibility meetings become lengthy, drift off topic, or devolve into contentiousness.

It also seems true that parents are apt to become bewildered by the arcane rules surrounding eligibility and by eligibility meetings’ ritualized nature. At least this is implied by findings from small-scale studies of parents’ perceptions of the eligibility process. For example, parents in a study conducted by Zeitlin and Curic (2014) felt that meetings were depersonalized, excessively focused on paperwork, and short on cooperation between themselves as parents and the school’s eligibility team members. In another study on the same topic, parents’ expectations failed to match the quasi-legal nature of the actual meeting (Canary & Cantu, 2012). It was as if two distinct cultural perspectives were clashing. This study also found an emphasis on the technical (e.g., recounting of test findings), too little time to cover procedures in depth, and extensive paperwork (i.e., obligation to process forms). Anyone who has attended more than a few eligibility team meetings is likely to recognize these themes. Most witnesses to the process can recount at least one “horror story” concerning a meeting that seemed to go on without end. The meeting might have witnessed the same topic visited and then revisited again and again, only to adjourn without ever achieving a resolution. What can school psychologists do to make the eligibility meeting process more humane and more effective?

Managing Eligibility Meetings

Here are some suggestions especially pertinent when a meeting’s topic is special education eligibility. They assume that school psychologists lead the meeting, although in some districts that role routinely goes to an administrator.

Set Expectations at the Outset

Simply put, a school psychologist say something like the following to all of those present: “We are here to get feedback on the evaluation that was just completed. With that feedback, we can decide if Maria is eligible for special education. If she is eligible, we can also decide what services to provide. As we move toward a decision, we have a checklist to guide us about eligibility. We have one hour in which to finish the meeting.”

Reset Expectations

If the team begins to spend too much time on topics tangential to eligibility, redirection may be needed. The following might be said, for example, to a parent who dwelling on past grievances: “Even though it was unfortunate that Maria’s second grade teacher might not have managed her behavior in the way that you wished, we need to go back to our task. Maria is now in the fifth grade and is encountering significant school problems. I’d like to get us all back to the topic of judging eligibility and making a plan for special education services. To do that we must determine if Maria has an educational disability.”

Watch Out for the Substitution Heuristic

At their core, eligibility questions involve satisfying a set of objective criteria (as you saw in Chapter 10). Each eligibility question, for each individual student, is a multi-faceted consideration that requires deliberate analysis and reflection. None should be made via snap judgements, subjective impressions, or wobbly logic. Unfortunately, humans are prone to decision making errors. Some of these are heuristics, mental shortcuts that lead to faulty conclusions as you saw in Chapter 2 (Kahneman, 2011). A prime example concerning eligibility determinations is the substitution heuristic. As you may recall, the substitution heuristic occurs when we unconsciously substitute a simple question for a complex one; answering the first question (the simple one), we may mistakenly conclude that we have answered the second question (the complex one). In an eligibility team meeting the substitution heuristic might take this form. A simple question before the team: “Would Maria benefit from resource help?” (i.e., a simple question that lends itself to intuition) gets substituted for a complex question that requires reflection and analysis, which is “Does Maria meet all necessary emotional disability criteria?” Once again, keeping eligibility criteria handy or working off of a checklist of eligibility criteria can prevent emergence of this troublesome heuristic (see the Checklist for Emotional Disturbance Qualification, Chapter 10).

Set and Adhere to Reasonable Timelines

It is interesting, and instructive, that the U.S. Supreme Court strictly limits oral arguments. Each Supreme Court case permits just 60 minutes of oral argument in total, 30 minutes for each side. And, of course, the Supreme Court renders the most consequential imaginable decisions. Should special education deliberations require more discussion than that afforded in our nation’s highest court? It’s hard to imagine they should. Consider notifying all attendees at the outset how much meeting time is available. Then be prepared to summarily wrap up the meeting (including eligibility judgments) before the sands of your hourglass have disappeared.

Write a One-page Summary to Prepare for an Oral Presentation

Regardless of your audience, your oral explanation needs to be clear and concise. Consider the following recommendation: write a single page document for parents that “includes a very brief summary of findings, bullet-points, diagnoses, and recommendations…it is also an excellent way…to clarify and organize thinking prior to sitting down with families (Postal & Armstrong, 2013, p. 269). Parents might read this in advance of an eligibility meeting (in concert with, or in lieu of, a parent-only feedback session). A drastically brief document forces its author to prepare a written variant of the 3-minute elevator speech (i.e., the type of speech in which the essence of a business proposal or a dissertation must be delivered simply and rapidly). There is room for nothing more than key points. If you prepare a letter, you might hold onto if during a feedback session with parents, when meeting with the students personally as well as during an eligibility meetings. Preparation of a one-page letter can promote clarity and conciseness, whether you glance at it during a meeting or recall its gist from memory as you speak with your audience. That said, it may prove utterly impractical to prepare a separate written summary for each parent. Most school psychologists are already overwhelmingly busy. However, the practice of doing so, even if only mentally, can prove to be an aid to concise thinking.

What about Oral Feedback for the Student?

All of the types of meetings mentioned above (e.g., parent-only feedback, eligibility meetings) concern primarily adult stakeholders. But what should you do to address the needs of the students themselves? Clinic-based psychologists seem at least somewhat equivocal about sharing assessment findings with children/teens. Logistical considerations may prompt questions about how to proceed. Is another clinic appointment needed to speak with the child? Should some of the office time allocated for parental feedback go to the youngster? Might it be best to have the children sit in for an entire feedback session if they have accompanied parents to their appointment? Fortunately, fewer logistical challenges exist in schools. Moreover, NASP professional standards (2020) imply that students should hear about findings (i.e., there is a requirement that students participate in decision-making). Sometimes, however, students themselves may be less interested than parents in hearing about assessment results. In addition, pre-teens may need especially simplified explanations. Even many adolescents will require quite uncomplicated explanations for the rationale behind their assessment, its essential findings, and what it means for short-term interventions and long-term potential needs. For these reasons, it is often helpful to meet with each student individually. Such meetings can be calibrated to a student’s personal level of understanding and interest. Meeting face-to-face with just the student can sometimes also help to debunk myths while simultaneously setting the stage for interventions (e.g., special services). With relatively unfettered on-campus accessibility, students might also be encouraged to return to the school psychologist if new assessment-related questions or concerns arise.

This topic begs the question about potential disclosure-related harm. In other words, might sharing findings cause the student psychological distress or set in motion counterproductive changes in self-perception? Perhaps. Josh, a 17-year-old high school student, had long thought that his problems in high school were due to test anxiety. He complained to his guidance counselor and his parents of seeming to go blank when confronted with school exams and especially in the face of high-stakes tests. A comprehensive psychoeducational evaluation produced findings that altered Josh’s self-conception. Measures of general cognitive ability placed him only slightly above average while revealing mild problems with long-term memory. In contrast to Josh’s preconceptions, there were only mild indications of anxiety generally (determined via rating scales and self-report measures). Even more critically, a detailed clinical interview suggested that anxiety reactions during testing were probably a consequence, rather than a cause, of poor test performance. Josh was indeed pained when he learned about the level of his cognitive scores. More broadly, he was left with a different conception of himself as a student, one that was arguably more negative.

Constance is a petite 7-year-old girl who has routinely been described by her family as “marching to the beat of her own drummer.” Her educational history includes strong academics but weak interpersonal skills and mild quirks (e.g., wearing exactly the same style and color of cotton dress every school day). Her parents fully embrace Constance’s uniqueness while recognizing that it imposes long-term challenges for her personal adjustment and ultimate happiness. Thus, they were only mildly surprised when they heard that their daughter met criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Constance herself seemed indifferent when she met with the school psychologist to hear about the results of her evaluation. In the weeks the followed, she rarely (if ever) thought about what her diagnostician had told her.

Jamal’s grades have cratered now that he is a high school freshman. He presently completes little schoolwork. Even more obvious, and more troubling, are a series of emotional outbursts during and between classes. Jamal comes from a military family, and both of his parents have attributed his always turbulent temperament to frequent moves and recurrent demands to adjust to a novel school and make another set of friends. Now his father is convinced that Josh’s “new attitude” represents blatant defiance of parental authority aggravated by poor sleep habits and selection of a band of friends best described as shady. A detailed evaluation, however, determined that Jamal is, like three close relatives, an individual with bipolar disorder. Learning that there are treatment options available outside of school plus educational options within it, Jamal’s parents relaxed and for the first time in many years thought optimistically about their son’s future. More importantly, Jamal’s sense of himself had changed. He was no longer puzzled by his mood swings (especially irritability) and he had stopped blaming himself over and over for poor emotional regulation. In addition, he is now better able to understand why sleep often proves so elusive and why he is sometimes plagued by racing thoughts.

Let’s think about these three thumbnail examples. Josh’s case seems to exemplify an unfavorable consequence of providing a student with post-assessment feedback. Constance’s case, however, seems to imply that sometimes feedback is largely inconsequential. But Jamal’s case brings up another possibility. It can be argued that going through an assessment process and receiving feedback about its findings (including a label) was beneficial. Consistent with the gist of Jamal’s case, trainers in child psychiatry sometimes contend that social-emotional assessments themselves (even before the launch of any interventions) turn out to be surprisingly therapeutic (Pruett, 2013). The very same contention is sometimes made by psychologists who champion detailed post-assessment information sharing. In their book describing the relevance and the particular methodology for providing assessment results, Postal and Armstrong (2013) include a chapter provocatively entitled “Providing the Correct Label Can be Therapeutic.”

It doesn’t take much imagination to envision optimism and relief among Jamal and his family after learning about his diagnosis and processing what it means for making sense of his disconcerting and perplexing array of behaviors. Such a meeting might reasonably be expected to remove the mystery surrounding Josh’s longstanding (and recently deteriorating) emotional state. Labels, although clearly capable of harm, can also promulgate good (see Chapter 1 for more discussion on labels in the assessment process). But once again, it’s not just about the potential utility of information sharing with stakeholders (including minors). Regardless of whether feedback with a student might be harmful (Josh), inconsequential (Constance), or potentially beneficial (Jamal), students still possess a right to know within the scope of their developmental level. For these reasons, psychologists often propose every child, or nearly every child, receive direct feedback (Dombrowki, 2020; Frick, Barry & Kamphaus, 2020).

Summary

The successful practice of school psychology rests nearly entirely on effective communication. And, there is no more vital information to communicate than assessment findings. When teachers and parents pose questions about behavior, adjustment and social-emotional functioning, school psychologists strive to answer clearly, concisely, and compassionately. They may do so orally or in writing. Among important considerations for oral communication with parents are the following: concentration on pertinent details only, use of everyday language, plus recognition that parents may harbor feelings of guilt or struggle with their own findings-related emotions. When special education is at issue, and meetings involve a team, oral communication must take on a quasi-legal focus. Checklists can help school psychologists to make correct judgments about eligibility as they avoid troublesome heuristics.