5 Broadband Rating Scales

Key takeaways for this chapter…

- There are now many parent- and teacher-completed rating scales (e.g., Behavior Assessment System for Children-3; Conners Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scale)

- Each of these offers scores on many social-emotional dimensions (e.g. anxiety, inattention) plus composite scores, all with the expenditure of minimal professional time and effort

- Favorably, most of these scales have large, representative standardization samples as well as evidence of acceptable reliability (and at least some validity research)

- Less favorably, not every individual dimension (e.g., social communication) has been researched, and some test manuals fail to provide sensitivity and specificity statistics

- Although manuals generally describe how to interpret their scores, most fail to indicate how to synthesize scores with background facts or with other assessment information (e.g., narrowband scales, interviews)

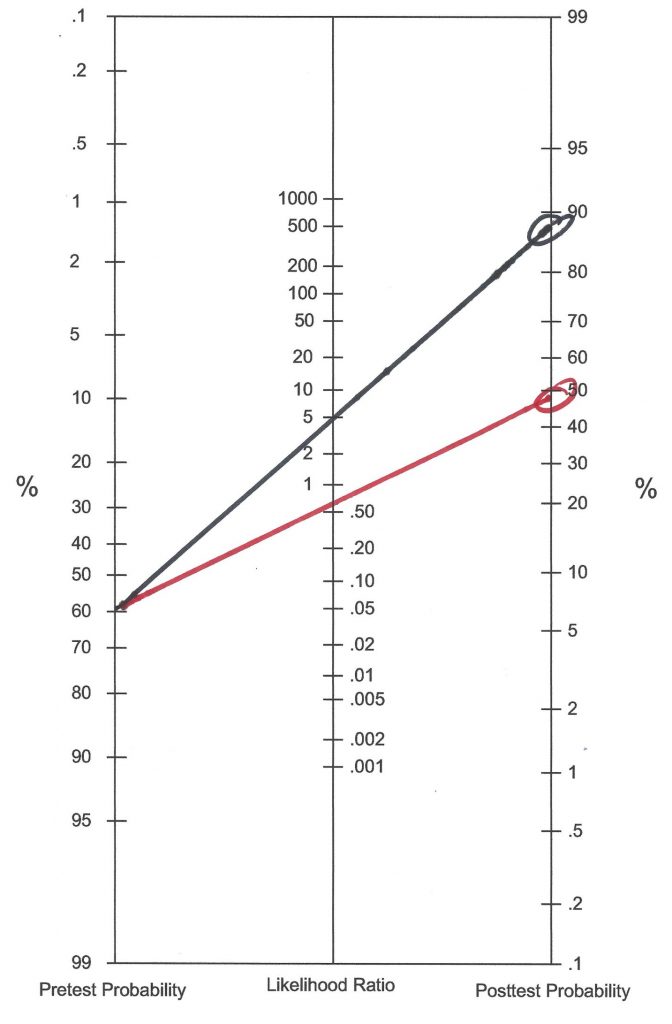

- For many referral questions, broadband rating scales help facilitate use of the HR approach, probability nomograms, and checklists

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- Clayton, questions about the validity of ratings

- Dr. Maritza, forced to used broadband scales

- Patrick, selecting broadband scales to round out an assessment

- Novella, remembering to follow the steps in interpretation

Now comes a critically important chapter. It is necessarily a bit longer. Please read and reflect. Broadband rating scales have achieved the highest usage rates of among all of school psychology’s assessment techniques used. To be specific, the BASC-3 parent version and teacher version, respectively, garnered the very highest ranking and nearly the highest among 150 assessment techniques (Benson, Floyd, Kranzler, Ekert, Fefer & Morgan, 2019). It’s hard to envision a contemporary school psychologist who finds no use for the broadband scales. In reality, most school psychologists’ offices include one or more popular scales resting on a desk or in a file cabinet. Broadband scales prove integral to many school-based social-emotional assessments, and they are often applied even when a referral question is initially unrelated to social-emotional concerns (e.g., routine SLD-oriented evaluations). But this book’s coverage of broadband scales requires a warning–you are cautioned against using these tools without first accessing their technical manuals. There are things you need to study among the 372 pages of the Conners Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scale (Conners, 2010). The same is true regarding the BASC-3’s 442-page manual (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015).

Similarly, this chapter is a mere introduction to broadband rating scales. And, to be clear, the chapter is not about selecting the best rating scale. Its pages are not designed to offer a scholarly review of the pluses and minuses of popular scales. If you wish to examine candidate rating scales side-by-side before selecting the best you should find reviews at online sources such as the Buros Center for Testing (https://buros.org) or texts such as Frick, Barry and Kamphaus (2020). These sources include important facts about topics like: age range, reading level, administration time, quality of norm sample, quality of reliability, and quality of conventional validity evidence. As you have already seen, conventional reliability and validity are necessary but not sufficient for some inferences that school psychologists make, especially about classification. Each of these scales provides vast information about its reliability and validity characteristics. Thus, those considering adoption of the BASC-3 should review the 55 pages concerning reliability and validity of the BASC-3 teacher version as well as the 50 pages concerning reliability and validity of the BASC-3 parent version. In these sections of the BASC-3 manual, one can find information about reliability (i.e., internal consistency, test-retest, inter-rater) as well as validity related to factor structure (factor analysis) and criterion (e.g., correlations with Conners CBRS, Autism Spectrum Rating Scale, Delis Ratings of Executive Functions, etc.). Similar, but not identical, reliability and validity information is available in the manuals of other broadband rating scales. In this chapter, we concentrate on application. Consequently, the topic of classification validity receives special attention, as you will see below.

With that notification out of the way, just what is the nature and make-up of this class of assessment tools? And how are they used in practice? These scales are called broadband because they assess many dimensions of social-emotional functioning. They are lengthy, with up to 500 objective items. Each item is read and rated by an informant, such as a teacher or a parent. For example, an item found on a scale for teachers might read as follows: “Student fails to pay attention.” Concerning this item, a teacher would select from four choices on a Likert-type scale: “always true,” “usually true,” “sometimes true,” “never true.” Raw score values would then be assigned to items, perhaps as follows:

- Always true = 3 points

- Often true = 2 points

- Sometimes true = 1 point

- Never true = 0 points

When many other items are included in the same scale (perhaps a scale entitled “Inattention”), then raw scores are tallied across items. For example, the Inattention scale, as part of a broadband rating instrument, might comprise 15 items, each scored on this zero-to-three continuum. The result would be raw scores ranging from 0 to 45 on the Inattention scale. By accessing age-specific and gender-specific norm tables found in the test manual, an Inattention standard score could be generated from the aggregated raw score.

Critically, broadband scales are generally organized hierarchically: relatively few composite scores (e.g., concerning internalizing problems or externalizing problems) are made up of constituent, fine-grained scales tapping dimensions like anxiety and depression or conduct problems and hyperactivity. The broadband scales also do more than just measure dimensions related to classic psychopathology; they can screen for delays in adaptive functioning or communication problems. As you may suspect, broadband scales also garner popularity for their ability to collect a lot of information with little effort. Importantly, they sometimes capture low-frequency behavior that may otherwise elude an observer whose classroom visits are necessarily time limited (Volpe, Briesch & Gadow, 2011). Given these facts, one can begin to envision the practical uses of broadband rating scales.

Other reasons also contribute to the appeal of these instruments. In their contemporary versions, many broadband instruments boast outstanding normative bases (large and highly-refined national samples), sophisticated factor analytic evidence, clearly-reported findings regarding reliability and validity (especially correlations showing convergence with other social-emotional scales). You will find some of these considerations are covered briefly at an instrument-specific level in this chapter. The same is true when narrowband scales are covered in Chapter 7, as well as for ADHD-related tools in Chapter 11 and autism-related tools in Chapter 12. Critically, however, this book concerns the process of social-emotional assessment. As such, it is not a text on social-emotional psychometric instruments.

Because this is the first chapter that includes psychometric tests, it’s important to put their use in context. Tests are used to answer questions. They help resolve unresolved hypotheses. They are not (or should not be) administered in evaluations merely pro forma, with no clear purpose in mind. The Reflective System of thinking should be in place before broadband scale use. Regarding the potential purpose for broadband use, sometimes it is clear, such as when the referral agent and the school psychologist agree on one of the questions found in Table 3.1. Please return to that table now and follow along with the points discussed below. It is obvious that one or more rating scales can help address several of the listed referral questions. Tests, supported by norms and concerned with classic test theory notions like reliability, are inherently nomothetic (McLeod, Jensen-Doss & Ollendick, 2013). They compare one student’s score(s) with many other students’ scores, hence enlightening the status of the one student by virtue of what is already known about many students. By the end of this chapter you will see that broadband scales are often helpful regarding referral questions 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, and 13, which are essentially nomothetic (and sometimes categorical). That is, popular broadband scales are especially qualified to speak to the prospect of recognizable social-emotional conditions (and mental health diagnoses) and to help establish severity. This information can also aid in establishing eligibility for special education services by helping you complete a checklist concerning necessary criteria. Importantly, because they systematically measure students across multiple domains of social-emotional functioning, broadband scales may be able to help establish which among many possible problems is most compelling. Broadband scales, of course, can also help confirm that no problems exist. And, because social-emotional problems often appear across multiple domains in the same individual, broadband scales can also address the issue of comorbidity. For example, scales like the BASC-3 can estimate whether any noteworthy social-emotional problem exists, its general nature (perhaps more internalizing than externalizing), and its fine-grained appearance (perhaps more indicative of anxiety than depression). You will see later that referral questions 3 and 9 in Table 3.1, universal screening (Renshaw et al., 2009) and progress monitoring (Busse, McGill & Kennedy, 2015), may also benefit from the use of broadband scales (or tailored variations of them). These topics are covered in Chapter 15. But if you think about the requirements associated with referral questions 1, 2, 4, and 5, rating scales may not be especially helpful. These are largely idiographic, not nomothetic, questions that concern the particulars of an individual’s life and her personality (Phillips, 2005). Consequently, other techniques are needed to adequately address these questions (e.g., clinical interview, behavioral observation, review of background information). This discussion reminds you to stop and think as you plan each student’s assessment. Similarly, don’t expect that broadband rating scales satisfy every requirement concerning social-emotional assessment.

A Few Things to Remember about All Behavioral Rating Scales

School psychologists are blessed with access to an array of rating scales. Few would quibble with the contributions of commercially available broadband rating scales to school-based practice. That said, this entire class of instruments needs to be considered in the light of harsh reality. Here are a few general things to consider before we look individually at several popular broadband instruments. Most of these pluses and minuses are equally applicable to narrow-band measures, the topic in the next chapter. For students who have not enrolled in a course on measurement principles, some of this information is likely to be especially relevant. There are also several helpful texts on mental measurement and psychological testing generally that you might want to access (e.g., Bandalos, 2018; Cohen & Swerdlik, 2018).

Objective, But Only up to a Point

Rating scales, of course, are comprised of perfectly uniform items. Importantly, every informant reads exactly the same items, in precisely the same order, following just the same directions. Items are forced choice; respondents select from among finite (objective) choices. These impressive objective hallmarks, however, should not disguise the inescapable subjectivity inherent in each item’s completion. Informants’ worldviews, their prior personal experiences, and the subjective meaning that they ascribe to items’ wording help drive which response options they ultimately select. This topic was addressed for school psychologists more than 25 years ago in an article with a wonderful title, “How many fidgets in a pretty much: A critique of behavior rating scales for identifying students with ADHD” (Reid & Maag, 1994). The essence of their argument is captured in the following passage. “The problems ….can be depicted by the example of ‘fidgets.’ Many instruments require a teacher or other adult to rate the extent to which the target child fidgets. Behavior rating scales, however, fail to operationally define what behaviors constitute a fidget, lack information indicating that fidget behaviors can be accurately captured, and, most importantly, provide no common metric for the scaling of the magnitude or intensity of fidget behavior. Thus, two separate raters could observe the same behavior and produce ratings that differ as to the presence or absence and frequency or intensity with the difference between ratings being due to factors internal to the raters rather than the child’s actual behavior” (Reid & Maag, 1994, p. 347). According to classical test theory, subjectivity-related differences due to the rater rather than the child being rated represent sources of measurement “error.” They help to contribute to low scale reliability. In the nomothetic world, and in the realm of classical test theory, low reliability is a problem. And indeed, the scores that arise from many behavior rating scales possess poor inter-rater reliability. These facts suggest caution regarding broadband scores. The cold, hard numbers you witness on a student’s broadband profile necessarily originated in the subjective world of a human rater.

Norm-referenced

Why are behavioral rating scales so enormously popular? One reason almost certainly is their norm-referenced feature. Norms permit a single individual’s score to be compared to scores of many individuals. This is the essence of the nomothetic perspective. The key is to access a representative sample so that score interpretations are accurate (Bandalos, 2018). For example, a 9-year-old student seems to be aggressive, and it would be possible to examine what an informant, such as a teacher, indicates about this possibility. Of course, this student’s level of aggressiveness might be scrutinized with or without accessing information about other 9-year-olds. Questions about aggressive actions might be posed orally or prepared in written form. Examples might include “bullies others,” “hits or pushes when angry,” and “shouts at classmates.” Even without norms to contextualize teachers’ responses, it is possible for a diagnostician to offer an estimate about this youngster’s level of aggressiveness, but there is no escaping the imprecision inherent in the process. As even novice school psychology students recognize, however, norms with which individual’s scores can be compared offer advantages. With norms, it becomes possible to judge whether a teacher’s level of item endorsement for a boy this age is common or uncommon, and to quantify the rarity of any outlier score. As you will see, with norm-referenced scores (such as T-scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10) diagnosticians find themselves armed with context enriched numbers.

Like popular counterparts that measure cognitive ability and achievement (e.g., WISC-5; Wechsler, Railford & Holdnack, 2014; Kaufman Tests of Educational Achievement-3, Kaufman & Kaufman, 2014), many broadband rating scales possess sophisticated norms. The Conners CBRS Teacher, as one example, was standardized on 2,364 representative youth (Conners, 2010). Both males and females were recruited across the age spectrum from 6 to 18 years. Besides gender and age, the dimensions of race/ethnicity, parental education level, and geographic location were analyzed to assure representativeness. Other rating scales boast comparable norm groups (see Table 5.1).

Sometimes, however, publishing companies intentionally seek non-representative samples, such as those comprised of youth with various recognizable conditions. These resulting so-called “clinical norms” offer a complement to standard (representative) norms. For example, BASC-3 users can access norms for students with ADHD, emotional/behavior disorders (EBD), ASD, Developmental Delay/Disorders, and SLD. School psychologists, of course, must carefully distinguish between general scores (i.e., those associated with a representative sample) from clinical-sample scores (i.e., those associated with specialized groups, such as youth with ADHD). A clinical group T-score of 50 (such as from a sample of students with EBD) indicates something quite different from a T-score of 50 associated with a general representative sample. The former, especially when coupled with a clinical range score derived from standard norms, suggests that the student’s score is both elevated and similar to a typical student with EBD. The latter, in contrast, suggests an unremarkable score.

Table 5.1 Broadband (Parent) Rating Scales and Their Standardization Samples |

|||

|

Rating scale name |

Standardization sample size |

Stratified with multiple census dimensions |

Additional clinical samples collected |

| Conners CBRS |

2,364 |

Yes |

Yes |

| BASC-3 |

1,800 |

Yes |

Yes |

| CBCL |

1,753 |

Yes |

No |

| Devereux |

3,152 |

Yes |

Yes |

Automated Scoring and Computer Printouts

The old days of hand-scoring broadband rating scales have largely disappeared. Nonetheless, some school psychology trainers still insist that their graduate students hand-score at least a few rating scales to gain a sense of the process and to see which items funnel into which scales. After graduate school, however, most school psychologists routinely use online scoring of BASC-3 and Conners CBRS, for example. Alternatively, scoring software can be purchased and downloaded on to one or a group of linked PCs, providing users the same technical advantages as online services. Besides time savings, automated scoring enables vast printouts (or online reading) of scores, interpretation and even explanatory/descriptive narratives. For example, a recently reviewed BASC-3 TRS printout comprised 37 pages, a Conners CBRS parent printout 41 pages. Included in printouts are things like scores, tables, symptom checklists, lists of items (including the exact wording of each), plus narratives for professionals to use (in report preparation) and even feedback handouts for parents. This degree of complexity represents a game changer when set against a mere page or two of scores (plus one or two graphic profiles) routinely available to broadband users 30 years ago. Every contemporary school psychologist will need to familiarize herself with the organization and content of the automated material associated with her preferred rating scales.

Informants Sometimes Produce Invalid Ratings

An individual’s rating scale scores may prove untrustworthy. For practicing school psychologists it does not matter whether this is considered a threat to “validity” (i.e., a test fails to measure what it says it measures; Frick, Barry & Kamphaus, 2020) or to “credibility” (i.e., reflecting a particular respondent’s bias or distortion; Youngstrom, Youngstrom, Freeman, de los Reyes, Feeny & Findling, 2011). Either conceptualization means that sometimes straightforward rating scale interpretation is rendered impossible. Favorably, both the BASC-3 and Conners CBRS are geared up to deal with distorted responses. Distortions may be conscious or unconscious, intended or unintended. They sometimes operate to exaggerate the severity of a child’s problems, whereas at other times to minimize them. As Table 5.2 illustrates, the BASC-3 contains five methods for ascertaining validity and response set. Validity scales like these were originally developed as part of personality inventories (e.g., the renown Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory) rather than those of an informant.

In the broadband scales you will see in this chapter, validity scales rely more on logic than empirical research. This means that it is not entirely clear how well they actually detect parents’ or teachers’ careless responding or their distortions. Furthermore, the validity scales may not possess sufficient reliability to accomplish their intended purpose. For example, parents’ validity scale scores reported in the Conners CBRS manual are not particularly favorable. In fact, the standard error of measurement (SEM) for the Conners CBRS Positive Impression T-score is a sizable 6.32; 6.00 for Negative Impression (averaged across age levels). Confidence intervals associated with values this large would create very substantial ranges of uncertainty surrounding a validity scale (approaching 12 T-score points). Thus, an observed Conners CBRS T-score of 59, on its face an average range score, could be associated with a true score in the elevated range (T-score > 70) if a 95% confidence interval were adopted. This leaves school psychologists with challenges in interpreting validity scale scores. If the concept of SEM is unfamiliar to you, then you need to examine the texts cited above (Bandalos, 2018; Cohen & Swerdlik, 2018) or find a credible online source.

Table 5.2 BASC-3 Validity and Response Set Indexes |

|

|

Name of Scale |

Intent |

| F index | To detect excessive negative ratings: “fake bad” |

| L index (self-report versions only) | To detect excessive positive ratings: “fake good” |

| V index (self-report versions only) | To detect basic validity—to check for endorsement of non-sensical items |

| Consistency index (Q-global scoring option only) | Check on reliability of responses (do similar items receive similar endorsement?) |

| Response Pattern index | Check on careless responding (a rated item agrees with immediately preceding item) |

Let’s see in the real world how “fake good” tendencies and “fake bad” tendencies might come into play. Consider the situation with Clayton. Clayton is now in the third grade, and the preceding three school years have been difficult for him. He has consistently struggled to complete work and to follow classroom rules. Clayton has three brothers, two of whom have diagnoses of ADHD and are treated with stimulant medications. His father was diagnosed with ADHD as a child; he is now bitterly opposed to the use of psychoactive medication and dubious of the entire notion of ADHD. Clayton had a psychoeducational evaluation completed in second grade that documented the presence of a specific learning disability in reading. But social-emotional issues were largely ignored. The local school district’s philosophy is one of PBIS and RTI. In fact, Clayton’s second-grade evaluation consisted of just academic testing (no cognitive or social-emotional measures). By midway through second grade, Clayton was receiving resource special education services. Now, as a third grader, he is undergoing an additional assessment at the insistence of his mother who wonders if her son may have a social-emotional disorder, especially ADHD. Although Clayton’s mother seeks an evaluation, she already suspects that he has ADHD. Moreover, she’s convinced that stimulant medications would improve his behavior and propel school success. Interestingly, Clayton’s third grade teacher is a notorious naysayer regarding all things mental health in general, and regarding ADHD in particular. Both parents completed their own Conners CBRS independently. As did Clayton’s classroom teacher. The profile coming from mother’s Conners CBRS was compatible with ADHD. But there was no evidence of ADHD from either father’s or teacher’s rating scales. Even without scrutinizing the Conners CBRS’s validity indicators, there is reason to question these scores. Perhaps, with or without conscious awareness, Clayton’s father and his teacher have slanted their responses toward the positive on every item that seemed ADHD related. The exact opposite might have been true of Clayton’s mother. School psychologists, of course, should look at validity scale scores for all three informants. But they should also use common sense to help them place these three sets of ratings in the context of trustworthiness.

Parents’ personal mental health problems may also matter. A depressed mother or father may be incapable of rendering a fully accurate (valid) rating of a child. For example, research demonstrates that parents with depression disproportionately engage in “disrupted parenting,” such as neglecting to attend to their children’s behavior or remaining ignorant of events in their lives (Reising et al, 2013). How could a parent fairly rate his child about whom he may know relatively little? Similarly, there are a few parents who experience pathologically obsessive preoccupation with their child’s perceived flaws. This is confirmed to be true among some parents themselves suffering from OCD (Doron, Derby & Szepsenwol, 2017). This phenomenon has been described as “relationship OCD,” a consideration likely to contribute to distorted parental ratings. Professional circumspection is clearly in order. The foregoing nothwithstanding, Youngstrom and colleagues (2011) argue that diagnosticians should be cognizant of all informants’ credibility on the one hand and slow to simply summarily dismiss such ratings on the other hand. This is because research by these authors implies outright elimination of ratings from potentially inaccurate sources may actually constitute an overcorrection that decreases, rather than boosts, diagnostic accuracy.

Rating scale scores might also be invalidated because of cultural and linguistic factors, especially those related to parent informants. It is certainly helpful that both the BASC-3 and Conners CBRS scales offer Spanish language versions of their parent forms. And the ASEBA Child Behavior Checklist has been translated into more than 100 languages, everything from Afrikaans to Zulu. But considering just Spanish, it is impossible to assume equivalence of concepts and vocabulary between the base English and subsequently-developed Spanish versions. This is true even when standard forward and backward translation are used. What’s more, even if a Spanish translation were perfectly executed, the problem of valid parent ratings would hardly be solved. For example, are psychological concepts (e.g., sad mood, behavioral noncompliance) equivalent across diverse immigrant communities (or subsequent generations holding comparable values)? Research shows that practitioners approaching emotional disability assessments among English Language Learners paid scant attention to parents’ level of acculturation as part of the evaluation process (Ochoa, Riccio, Jimenez, Garcia de Alba & Sines, 2004). Unfortunately, questions about equitable and clinically-reasonable management of cultural and linguistic considerations, like those concerning the general risk of invalid ratings, appear to lack simple answers. Again, circumspection and caution seem to be needed.

Situational Demands Influence Ratings

Recall the case of Franklin from Chapter 2. This young man appeared to be suffering distress during two classes but not during several others. The problems appeared to be superimposed on a shy temperamental style. Franklin’s case was pulled together without the use of rating scales, although scales could have been easily used. How might stakeholders’ rating scales looked if they had been used? It’s probable that social-emotional scores coming from those classrooms that Franklin avoided (where he was distressed) would look different from those classrooms he never avoided (where he apparently was not distressed). Similarly, is it plausible that ratings coming from Franklin’s parents would match those coming from school? Probably not. This is so because parents had long seen their son as temperamentally shy but apparently had never seen him as frankly unhappy.

This illustrates an important potential consideration—behavioral ratings can diverge simply because students’ behavior sometimes differs from one setting to another. This is wholly expected when an idiographic perspective is adopted. From this perspective, scores need not be about a fixed trait alone (as they are from the nomothetic perspective and according to classical test theory) but also about a student’s unique set of school situations and the vast ways that they may influence his presentation (Frick, Barry & Kamphaus, 2020). Such a view of score differences is particularly relevant when ADHD is a possibility. For example, classrooms, which typically require focus and persistence to complete work, are often inherently more demanding than relatively free-play environments that sometimes exist at home, which may demand little focus and no task completion (Hartman, Rhee, Wilcutt & Pennington, 2007). Few school psychologists should be surprised, then, when informants in the first setting rate a child as evidencing greater attention problems than informants in the second setting.

In fact, the intuitive idea of less-than-perfect concordance among raters is documented in actual data sets. For two teachers rating the very same student on the Conners CBRS Conduct Disorder scale, for example, the inter-rater correlation was just .40 (Conners, 2010); the inter-rater correlation between two parents’ ratings regarding Conduct Disorders was .53 (Conners, 2010, see p. 159 and p. 160). Similarly, two teachers rating a child on the BASC-3 produced these representative correlation values: Anxiety r = .35; Aggression r = .56 (for school-age children; see Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015, p. 127). Correlations between school-based and home-based informants are, of course, more modest (e.g., BASC-3 child, Anxiety r = .29, Aggression r= .37; Reynolds & Kamphaus, p. 228). When scores disagree across raters, the source may reflect legitimate differences in expectations and demands. But some of the disagreement may also reflect lack of reliability on the part of each independent rater.

Whatever the source, unfortunately, divergent scores represent a challenge for interpretation. Fortunately, sometimes discrepant scores represent important diagnostic clues. In Franklin’s case, for example, had clinical range scores from certain teachers appeared in the presence of average-range scores from other teachers then some hypotheses would have been strengthened, others weakened. Specifically, hypotheses regarding situational explanations (rather than invariant student characteristics) would have seemed more compelling. At any rate, readers are encouraged to examine the manuals of the instruments that they intend to use. This includes checking for themselves inter-rater reliability values. They are also cautioned about taking any rating scale score as an indication of a static trait that ought to appear identically (or nearly-identically) across situations.

Critical Items Serve as Red Flags

Most broadband scales offer diagnosticians a few especially relevant (critical) items to consider. The BASC-3, for example, specifies that endorsement of any of its critical items “suggest(s) danger to the well-being of the child or others” (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015, p. 62). Practically speaking, unusual endorsement of any critical item warrants follow-up inquiry. It’s easy to recognize why threats to hurt others or expressions of a wish to be dead are critically important. Consequently, regardless of a particular case’s referral question, it makes sense to conduct a check to make sure no critical items were endorsed (Note that the HR Worksheet [see Chapter 2] includes a requirement that you checkoff having examined critical items). The BASC-3 printout facilitates the process—critical items that are strongly endorsed appear in bold font. In parallel, critical items with unusual endorsement on the Conners CBRS are literally denoted by a red flag on the printout, easily grabbing school psychologists’ attention.

Linkage to DSM-5 Symptoms

When school psychologists view a student relative to DSM-5 criteria, broadband scales can help. That is, for school psychologists approaching a formal DSM-5 diagnosis, popular tools (e.g., BASC-3 and Conner CBRS) provide several DSM-related symptom scales. Relatedly, there are printouts that list teachers’ and parents’ level of endorsement of each DSM symptom concerning several child-specific diagnoses (e.g., ADHD, autism spectrum disorder). Caution is required, however. This is because the precise wording of rating scale items and that of DSM-5 rarely match. This fact means that parents and teachers would need to be interviewed before all criteria necessary for a DSM-5 diagnosis could be satisfied. Still, a printout might speed the symptom confirmation process. The topic of categorical decisions, including use of broadband scales to support the process, will be revisited in Chapters 11 (regarding autism) and 12 (regarding ADHD).

Just What is Being Measured?

One challenge is common to every rating scale seen in this book. That is the critical question of whether test descriptions match test content (i.e., content validity). Take anxiety as an example. Anxiety is obviously multifaceted–it might encompass several things: some subjective and covert (e.g., worry and apprehension) and some objective and overt (e.g., physical signs such as sweaty palms and a racing heart). Consequently, when broadband rating scales include an anxiety index, that index should be comprised of items concerning both of these aspects of anxiety. When a test does this (i.e., when it captures all aspects of a construct) it is said to enjoy full construct representation (American Educational Research Association [AERA] et al., 2014). When it fails to do so, it is guilty of construct underrepresentation. To achieve full construct representation, it is only logical that one should know precisely what the construct is made up of. This would depend on a definition of the construct and a sense of boundaries of that construct (e.g., what is included in the notion of anxiety and what is excluded, according to the authors notion [theory] of anxiety). Thus, a good definition is essential, even if only sometimes provided explicitly. Deborah Bandalos, in her text on measurement, warns “many researchers [or test developers] gloss over this step, feeling, perhaps, that the definition of the construct being measured is self-evident. Nothing could be further from the truth, however” (Bandalos, 2018, p. 43).

When you examine test manuals of broadband rating scales ask yourself whether the tests’ authors defined their constructs. Also, ask if there are a sufficient number of items available to fully represent each construct. Sometimes the answers to one or both of these questions will be no. This bears on the confidence you can afford scores in your practice. Behavioral rating scales like the BASC-3, for example, certainly list the items that make up each of their clinical scales. And there are descriptions of scales to aid score interpretation, but the BASC-3 manual seems to fall short of a precise definition of its constructs. Furthermore, relatively few items make up some BASC-3 clinical scales. For example, the BASC-3 includes an adaptive scale entitled Leadership. This scale is made up of just 9 items. When school psychologists interpret the Leadership scale, they are encouraged to ask themselves whether these 9 items adequately capture the notion of leadership.

There is a problem related to, but distinct from, construct underrepresentation. This problem concerns construct irrelevant variance (AERA et al., 2014). Construct irrelevant variance concerns inadvertently measuring aspects unrelated to the construct under consideration. In other words, construct irrelevant variance has to do with including items that don’t belong rather than insufficient items that do belong. Again, consider the BASC-3 Leadership scale. Of the 9 items in this scale, one item asks the rater if the child is creative. Is creativity part of Leadership? Your intuition may say no. Again, a solid definition of leadership would help. Of course, there is more to the process than examining individual items and their congruence to stated definitions. Statistical methods can help answer this question. Decrements in the correlation between a scale (e.g., BASC-3 Leadership) and other (well-established) measures of leadership upon introduction of a new (dubious) item signal psychometric evidence of construct irrelevant variance.

In part, the items that make-up various scales and indexes are guided statistically, not by mere human judgment. For example, test authors sometimes look at item placement via correlations between each individual item and an entire scale where they might fit (part-whole correlations). Relatedly, item placement can be guided by intercorrelations among various scales so as to find the best statistical matches between items and scales (factor analysis; DeVellis, 2012). Again, school psychologists are obliged to familiarize themselves with test manuals, including some general knowledge about the method and rationale for item formulation, placement and final item-level retention.

Stand-alone Test Interpretation Versus Comprehensive Assessments

It’s essential that the manuals of broadband rating scales indicate precisely how to use them in practice. Indeed, manuals often include an description for multi-step interpretation. Test users, for example, might be prompted to start by examining validity scores, then to consider one or two global mental health-scale scores before turning to a dozen or so finer-grained mental health-scale scores. High scores, of course, imply social-emotional problems, either categorically or dimensionally. Critically, however, manuals sometimes read as if diagnosticians are informed only test scores. In reality, this should never be the case. Stand-alone interpretation guided solely by a test manual’s script risks the WYSIATI heuristic (see Chapter 2). In other words, what you see about the child is what is found only (mostly) in her rating scale results—that’s all there is. But, in reality, as you have already learned, broadband scales are seldom used in isolation. As the cases you have seen so far reveal, these instruments are used to answer referral questions within the context of a school concern, rather than to describe a child in a vacuum. Depending on the question, the process of assessment evolves over time. It is not one of administering a test, looking at a profile, considering cut-scores, and then blindly describing a child. In other words, these tests are typically employed as part of a process like the one described as HR. Fortunately, in reading test manuals, you’ll see that there is at least implicit recognition of this reality. This book’s approach advocates (usually) employing test scores as part of a comprehensive process. You are obliged to read the manuals, but you were also obliged to practice in the best interest of the child. Remember the advice you heard earlier in this book: interpret the child, not the test. Accordingly, be cautious of stand-alone test interpretation.

Cultural-Linguistic Considerations and Broadband Scales

In Chapter 4 we addressed the importance of cultural and linguistic considerations when collecting background information. Thus, it’s hardly a surprise that these factors are also relevant in the current chapter regarding broadband rating scales. Two considerations merit attention: (1.) linguistic barriers to using broadband rating scales, and (2.) cultural barriers to using broadband rating scales.

Linguistic Barriers and Broadband Rating Scales

You were already urged (in Chapter 4) to routinely consider linguistic barriers while talking with parents. Specifically, it was argued that parents lacking English oral proficiency should prompt use of a trained interpreter. Following just the same logic, parents who cannot read English well (but who possess literacy in a foreign language) probably require a translated broadband rating scale. Happily, most popular scales provide Spanish language translations. Interestingly, scales used less often in schools, specifically the ASEBA Child Behavior Checklist (CBLC) and the Teacher Rating Form (TRF), both detailed later in this chapter, offer far more than just a singular Spanish option. In fact, the CBLC’s publisher (Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment; ASEBA) provides translations for more than 100 languages and dialects. This reality represents a bit of a paradox. The BASC-3’s teacher and parent completed options are the most popular of all rating scales. Yet the far less popular TRF and CBCL (16th and 17th most popular rating scales among school psychologists; Benson, Kranzler, Floyd, Eckert. Fifer & Morgan, 2018) afford many more options for practice in a rapidly evolving multicultural country.

The challenges associated with producing a credible translation are worth brief contemplation. One challenge is to create a version that matches the content of the standard English version. In other words, each item in a standard English version rating scale must be faithfully translated into another language, such as Spanish. As many readers know, there is an accepted methodology for such translations. The first step is to translate each item into the target language. Although this straightforward first step might be intuited to render a trustworthy alternative version, things are not so simple. Each item in the translated version may or may not be construed by readers differently than the standard English items that spawned it. If items in a new (non-English) version are matched well, then there is said to be high translation fidelity (Bontempo, 1993). The conventional method to improve translation fidelity is back translation. The new (non-English) version is retranslated into English. This permits the original and back translated versions to be compared side-by-side. Faulty aspects of the translation can then be corrected, ultimately producing a non-English version with strong translation fidelity. Fortunately for our purposes, most popular broadband scales perform such a back-translation procedure for their parent-completed versions.

Another translation-related challenge involves language within the context of culture. Translators must possess expertise and knowledge about child development, behavior, and family life within the culture in question. This is true because translating rating scale items is not the same as translating a poem or a diplomatic document. Regarding the Conners CBRS, three Spanish speaking staff members at MHS (the publisher of this instrument) created three preliminary Spanish versions. MHS then used the services of an expert bilingual school psychologist, Dr. Sam Ortiz. Dr. Ortiz reviewed preliminary items for their readability, content, and cultural sensitivity regarding use in the United States. Two other Spanish-speaking school psychologists then back translated items into English. This permitted scrutiny and ultimate item revision via repeated iterations. This process rendered a final version of the Spanish Conners CBRS. Roughly comparable procedures were used regarding the BASC-3’s Spanish version for parents. In the case of the Spanish-version BASC-3, however, 10 bilingual professionals (from psychology and education) employed by Pearson (the publisher of this instrument) conducted the analysis for accuracy and bias. Like the Conners CBRS, the BASC-3 analysis sought to create a Spanish version for use with parents in the United States.

Cultural Barriers and Broadband Rating Scales

As you also saw in Chapter 4, language is one consideration, cultural attitudes and practices another. Sometimes parental language and culture overlap, but sometimes they dissociate. Thus, although it is true that French (or a French variant) is used many places (e.g., France, Belgium, Haiti, Canada, Congo), it is also true that inhabitants (and immigrants) from these countries harbor meaningful cultural distinctions. This implies that a French-language version of a rating scales (e.g., ASEBA-CBCL) maybe a good starting place, but it may represents a poor stopping place. This is so because it would be impossible for just one English-to-French translation to capture the array of nuanced culture and language considerations found in various French-speaking locations. The same is arguably true of any English-to-Spanish translation. As you will see below, the CBCL and Teacher Report Form (TRF) offer alternative norms enabled by samples collected in many countries using translated versions of the CBCL or TRF. The ASEBA website section entitled “Societies with Multicultural Norms” lists more than 50 such instances. https://aseba.org/societies/. Just a few are listed here.

- Brazil

- China

- Croatia

- Hong Kong

- Iran

- Israel

- Jamaica

- Kosovo

- Puerto Rico

- Taiwan

- Thailand

The idea is that a school psychologist might offer parents a foreign language CBLC that simultaneously provides her with multicultural norms to aid her interpretation. Of course, this would be applied to parents now residing in the United States who presumably once matched the demographics of these various non-U.S. norms. But the parents now reside in the United States and are consequently assumed to be reflected in the norms of the English CBLC. This constitutes a conundrum. A solution is to do two things. First, use both the standard U.S. as well as the specific multicultural norm. Resulting student profiles can be compared for agreement and disagreement, with priority of one profile over another judged against other information (such as found in the HR Worksheet). Moreover, multiple informants can rate the same youngster. Item level analysis is also positive. In an ideal world, an interpreter with detailed cultural knowledge might finally scrutinize the process for misunderstanding. Clearly caution is in order. Simply finding a rating scale whose items match the primary language of an informant may not suffice. Sensitivity to language and culture are required any time a student from the non-dominant culture is assessed.

A Few Popular Scales, Briefly Considered

We cover the organization and general features of four broadband teacher and parent scales. You have already seen that all such scales share features. Thus, individual comparisons of these universal dimensions are not included here. That said, for practical reasons we do address the topic of diagnostic utility statistics for each of the four scales. This coverage is important because diagnostic utility statistics provide a sense of how well the measures work for classification purposes (and the nomothetic perspective). Equally important, values indicated here might set the stage for applications in probability nomograms (see Chapter 2 for details on this methodology). Even without an in-depth review of broadband scales, the chapter offers some sobering facts. Some manuals are missing important information and/or seem to mischaracterize some of their capabilities. By the end of the chapter, your continued admiration for broadband rating scales should be tempered by the reality of what they can actually accomplish. You will see a similar perspective regarding personality inventories and self-report measures in Chapter 6 as well as regarding narrowband scales in Chapter 7.

Behavioral Assessment System for Children-Third Edition (BASC-3)

The BASC-3 is described by its authors as “a multimethod, multidimensional system used to evaluate the behavior and self-perceptions of children and young adults ages 2 through 25 years” (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015, p. 1). In this chapter, only the teacher (Teacher Rating Scale; TRS) and parent rating (Parent Rating Scale; PRS) for school-age children are covered. Self-report scales, developmental questionnaires, and observational techniques are also available in the BASC-3 suite. So too are rating scale versions devised for pre-school age children and college-age students, although these are not covered here. You will need to read the manual if you choose to use the BASC-3. In this chapter you will receive an overview, information on some studies using the BASC-3 (or an earlier version, the BASC-2), plus introduction to its use in practice. The Skills Workbook provides more detailed information on application.

BASC-3 Organization and Characteristics

Table 5.3 is a summary of the clinical scales found in the BASC-3 (i.e., TRS and PRS) and an overview of its organization. This table is worth studying because it conveys some of the logic behind the BASC-3. The table also begins to reveal how the BASC-3 might be used in practice (and hints at the source of its vast popularity).

Let’s start with the BASC-3’s Behavioral Symptoms Index (BSI) and see what the manual advises about interpretation. The BSI is examined clinically only after any validity concerns have been resolved (as covered earlier in this chapter [Table 5.2] and detailed in the manual). BSI represents an important composite derived from six narrow clinical scales (i.e., Hyperactivity, Aggression, Depression, Attention Problems, Atypicality, Withdrawal). As such, it enjoys both reliability and breath of content sufficient to help address a summary question—are ratings generally compatible or generally incompatible with a mental health problem (irrespective of type)? The BSI thus affords diagnosticians something more or less akin to a global social-emotional disturbance index. Examination of more fine-grained scales can follow, based in part on what the BSI conveys.

Next consider composite scores, some of which rest on long-established empirical foundations. For example, groundbreaking factor analytic studies conducted more than 50 years ago discovered that some symptoms cluster consistently across many, many raters. Specifically, ratings of children’s symptoms often group into two clusters that came to be described as “externalizing” as distinct from “internalizing” (Quay & Quay, 1964a; Quay, 1964b). As seen in Table 5.3, on the BASC-3 TRS and PRS each of the Externalizing and Internalizing composite scores derives from three narrower clinical scales. Contemporary studies continue to document the externalizing-internalizing distinction (Kendler, Prescott, Myers & Neal, 2003; Wright, Kreuger, Hobbs, Markon, Eaton & Slade, 2013). And, most school psychologists are familiar with both presentations. Children scoring high on the former largely represent problems to others (e.g., teachers, parents), whereas those with elevations on the latter largely represent problems to themselves. Accordingly, the BASC-3 reports Externalizing and Internalizing composites scores.

Other BASC-3 composites concern School Problems and Adaptive Skills. In some ways, these latter composites seem to logically reflect the distinction between social-emotional symptoms and signs on the one hand and impact on the life of the child on the other hand. For example, assume that a student’s BASC-3 profile reflects externalizing problems (signs of a mental health condition) coupled with diminished social skills and poor adaptability (adaptive impairments). These kinds of distinctions are practically important for school psychologists in general as well as specifically concerning the BASC-3. In fact, the notions of “disability” and “disorder” require documentation of real-world impact. An intellectual disability, for example, is not just low IQ. It is low IQ and concurrent impairments in adaptive behavior (American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, http://www.aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition. In parallel, IDEA (a disability law) imposes requirements such as “adverse educational impact” in order to designate a student as disabled https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.8. In much the same vein, DSM-5 requires impairment (sometimes across several settings) for confirmation of many of its diagnoses (symptoms alone are insufficient to indicate the presence of a mental health disorder). All of this means that evidence of low adaptive functioning on the BASC-3, quantified by standard scores and resting on a large standardization sample, might prove quite helpful.

Table 5.3 BASC-3 Teacher Rating Scale and Parent Rating Scale Clinical Scales & Composites |

|||

|

Teacher |

Parent |

Self |

|

| EXTERNALIZING + Composite Score | |||

| HyperactivityBSI | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AggressionBSI | Yes | Yes | No |

| Conduct Problems | Yes | Yes | No |

| INTERNALIZING + Composite Score | |||

| Anxiety | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| DepressionBSI | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Somatization | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

OTHER + Composite Score (School Problems) |

|||

| Attention ProblemsBSI | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| AtypicalityBSI | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| WithdrawalBSI | Yes | Yes | No |

| Learning Problems | Yes | Yes | No |

| ADAPTIVE + Composite Score | |||

| Adaptability | Yes | Yes | No |

| Social Skills | Yes | Yes | No |

| Leadership | Yes | Yes | No |

| Study Skills | Yes | No | No |

| Functional Communication | Yes | Yes | No |

| Activities of Daily Living | No | Yes | No |

| BSIItems on this scale contribute to the Behavioral Symptoms Index | |||

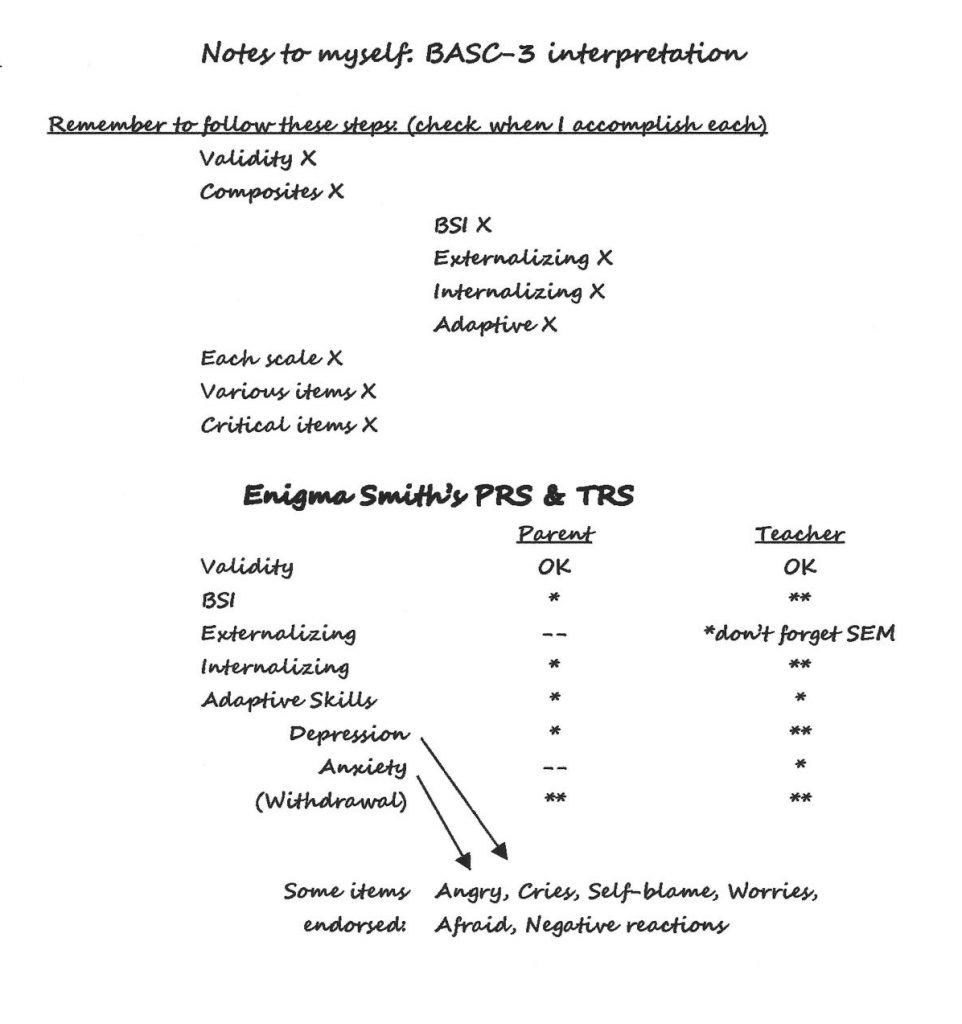

Next consider the BASC-3’s narrower clinical scales as seen in Table 5.3. It’s apparent that many match, at least in name, common mental health conditions described in Chapter 1 (e.g., depression, anxiety, conduct problems). Importantly, however, the manual offers advice, and at least a modicum of caution, about interpreting clinical scales. For example, before school psychologists look at fine-grained scales, they should scrutinize over-arching composite scores. This method of analysis helps school psychologists remain cautious about inferring specific problems (those related to inattention, hyperactivity, depression, anxiety) without first confirming the presence of a general problem. This method of sequential interpretation may remind school psychologists of interpreting the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-5th ed. (WISC-V; Wechsler, Railford & Holdnack, 2014). On the WISC-V, full scale IQ is typically examined before one scrutinizes narrower index scores (e.g., Verbal Comprehension Index, Perceptual Reasoning Index) or subtest scores (e.g., Block Design, Vocabulary; Kaufman, 2016).

It may be already apparent that top-down interpretation can help constrain false positives. Imagine a school psychologist who skips over composite scores and then uncritically scrutinizes many narrow rating scale scores, each of which is imperfectly reliable. Because of reliability considerations alone, one or two scores may be elevated owing to chance. To conclude that you have found something important based on a single elevation like this is akin to a researcher who runs the same experimental versus control comparison on one dependent variable, then another dependent variable, then yet another…until she eventually finds a dimension on which the experimental group outperforms the control group. This is a cardinal research sin. It involves making a Type 1 error (equivalent to finding a false positive in clinical settings). Following the BASC-3 manual (i.e., start with the BSI and composites and move extremely cautiously if they are not elevated) may help reduce such errors.

Individual items (e.g., those asking a teacher or parent to rate a child’s activity level or his level of nervousness) might be examined next. Item level analysis requires even more caution. For example, if the BSI, Internalizing Problems, and Anxiety scales were all elevated, then the school psychologist might zero in on each of the BASC-3’s Anxiety items (i.e., 9 items rated by teachers and 14 items rated by parents). But it is dubious to scrutinize a single (unreliable) item absent composite elevations. When item level analysis does occur, diagnosticians can find all individual items in a printout. This makes it easy to see how a teacher or a parent rated each (e.g., perhaps strongly endorsed the presence of fear but not of pervasive nervousness). It is true that broadband scales are inherently nomothetic (they compare one student to many). Nonetheless, an idiographic purpose can also sometimes be served (knowing a student uniquely) via inspection of item-level responses. Of course, for some referral questions it is interesting to discover which items a teacher strongly endorses and which items they may not endorse at all. Detailed analysis like this might help add clarity to a particular scale elevation. Planning an intervention may also be easier if quite specific symptoms are recognized (a topic covered in Chapter 15). Novella Smith’s case management, covered later in this chapter, shows how item level information might inform the student interview process.

What about the critical item (red flag) feature? There are 13 “critical items” contained in the teacher and 23 “critical items” found in the parent BASC-3. Specifically, strongly-endorsed BASC-3 critical items show up in printouts with a bold font. Thus, it’s easy to see if a teacher or a parent has noticed a health problem (e.g., seizures), destructive behavior (e.g., fire setting), or tendencies for self-harm (e.g., a desire to be dead). These can help the school psychologist perform due diligence. If a teacher or a parent endorsed any of these, follow up would required. In fact, inclusion of critical items in printed form might speed parent or teacher interviews. The same is true regarding student interviews. You will see in Chapter 9 that the Generic Child Clinical Interview form requires diagnosticians to examine critical items every time a behavioral rating scale is used in conjunction with a student interview.

BASC-3 and Classification Validity

You learned about the importance of classification validity in Chapter 2. Recall that when binary diagnostic decisions are made (e.g., autism is present vs. autism is absent), then some simple computations can result in practice friendly statistics. These are sensitivity (rate of correct classifications of those with a condition) and specificity (rate of correct classifications of those without a condition). Like broadband scales generally, the BASC-3 is designed to assist in categorical decisions, including mental health diagnoses. This is not the only thing that these tools purport to do, but it is one thing that is intensively important. And to be fair to the BASC-3 authors, use of information from social and developmental history and from observation, both enabled by elements of the BASC-3 family, are advocated in the manual. But BASC-3 scores (i.e., from the TRS and PRS) are often central to those in the field. In fact, scores above the clinical level cut-score of T-score = 70 may get prime consideration in making diagnoses. And, indeed, diagnosis is at issue. In the words of the authors, “…the BASC-3 components aid in the clinical diagnosis of disorders that usually first appear in childhood or adolescents” (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015, p. 8, underline added). Clinical diagnoses relevant to school psychologists are, of course, those like ADHD, anxiety, depression, and autism.

Here’s an essential point: the BASC-3 manual provides nothing at all on the topic of sensitivity and specificity. Consequently, BASC-3 users are unable to go to the test manual for information necessary to create Diagnostic Likelihood Ratios (DLRs); see Chapter 2 for details. Among other limitations, this means that the manual does not enable use of probability nomograms. More broadly, school psychologists must operate lacking a key effect size indicator concerning classification validity (i.e., DLRs). We’ll see if the BASC-3 might address classification evidence a bit later. But for now, absent information from the manual, we’ll consider the post-publication peer reviewed literature and diagnostic utility statistics for the BASC-3 (and BASC-2).

Three published studies-concerning autism (autism spectrum disorder [ASD]) and ADHD–provide a sense of what has been done. In the first study, the 13-item Developmental Social Disorders scale from the BASC-2 was shown to distinguish youth with and without ASD (see Table 5.4; Bradstreet, Juechter, Kamphaus, Kerns, & Robins, 2016). The study implies that an elevated Developmental Social Disorders score probably contributes to correct ASD classification but effect sizes are rather modest. That said, added to other information DLRpositive values as high as nearly 3.0 and DLRnegative values as low as .33 might make meaningful contributions to probability nomograms. In a second study, two values from the BASC-3 PRS and TRS as well as the Autism Probability Index were documented to classify youth with ASD (see Table 5.5 Zhou, Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2021). Note that positive DLRs were associated with rather modest effect sizes, whereas negative DLRs were associated with larger effect sizes. This implies that negative scores (those below the cut-point) worked relatively better in this study (and perhaps in practice). In a third study, several BASC-3 scales in concert, not just the obvious Attention Problems and Hyperactivity clinical scales, were used to classify those with ADHD (see Table 5.6; Zhou, Reynolds, Zhu, Kamphaus & Zhang, 2018). Except for DLRnegative from parents, the effect sizes are not particularly impressive.

These three post-publication studies seem to concern the capability of BASC-3 scores to classify but they do so in a broad (research) sense. Thus, they may offer limited applied use. Indeed, researchers used cut-scores honed to their studies rather than the traditional T-score of 70. For example, Bradstreet and colleagues used cut-scores as low as 60; Zhou and co-researchers found that extremely low-cut scores were required to maximize correct detections and minimize incorrect diagnoses (e.g., 57 for Attention Problems; 54 for Hyperactivity). Also, researchers sometimes used sophisticated score combinations that practitioners may never themselves calculate. Also, each of these three studies represent stand-alone efforts without replication. This means that the sensitivity and specificity values (as well as resulting DLRs) reported would be unlikely to appear the same in a second, independent study. Cross-validation of the values seen in the preceding tables would need to occur via follow up studies if practitioners are to truly trust DLR values (such as for use in their own probability nomograms). Again, it is post-publication resources, not the test manual, that provides BASC-3’s users with diagnostic utility statistics (C. R. Reynolds, personal communication, May 9, 2022).

Table 5.4 Effect Sizes and DLR values for BASC-2 Developmental Social Disorders scale concerning Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) |

||||

| Comparison | Effect size associated with positive score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Positive | Effect size associated with negative score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Negative |

| 1ASD vs. non-ASD | Minimal |

1.9 |

Minimal |

.44 |

| 2ASD vs. no diagnosis | Small |

2.8 |

Small |

.33 |

| 3ASD vs. other diagnosis | Minimal |

1.7 |

Minimal |

.60 |

|

1Cut-score T-score = 61;2Cut-score T-score = 60;3Cut-score = T-score = 63. Adapted from Bradstreet, et al. (2016)

|

||||

Table 5.5 Effect Sizes and DLR Values for the BASC-3 concerning ASD |

||||

| Source of Rating | Effect size associated with positive score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Positive | Effect size associated with negative score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Negative |

| Parent 3 scales | Small | 4.75 | Large | .06 |

| Parent Autism Probability Index | Small | 4.61 | Large | .04 |

| Teacher 3 scales | Small | 4.10 | Moderate | .18 |

| Teacher Autism Probability Index | Small | 2.97 | Moderate | .12 |

| Source: Zhou, Reynolds and Kamphaus (2021) | ||||

Table 5.6 Effect Sizes and DLR Values for BASC-3 Concerning ADHD |

||||

| Source of Rating | Effect size associated with positive score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Positive | Effect size associated with negative score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Negative |

| BASC-3 Teacher Report Form, several scores combined | Small | 2.6 | Small | .31 |

| BASC-3 Parent Report Form, several scores combined | Minimal | 1.9 | Moderate | .12 |

| Adapted from Zhou, Reynolds, Zhu, Kamphaus & Zhang (2018) | ||||

Skeptical readers might ask why there is a need to consider diagnostic utility statistics and the BASC-3. After all, this topic may have been foreign to them before reading this book’s Chapter 1. Moreover, topics like sensitivity, specificity and DLRs are rarely on the lips of their colleagues and supervisors. Maybe the BASC-3 manual is simply giving users what they want, and they don’t really care about sensitivity and specificity. Regarding the BASC-3, its manual gives readers average values for various clinical samples, perhaps to demonstrate that scores work for classification. You can see a few of these in Table 5.7. By the way, the manual does not appear to include statistical differences between clinical and control groups (a shortcoming you were warned about in Chapter 2 via the example of men’s and women’s heights). Check out the Table 5.7 (also consider visiting pages 161 and 213 in the manual for many, many more mean values). It should be obvious from Table 5.7 that BASC-3 scores cannot classify perfectly. In fact, mean values for many clinical groups fall into the “at risk” range (short of the “clinical range”). Plus, for some clinical groups, means for scales that should seem to, intuitively, be elevated are found to actually fall in the “average range”. Logically, school psychologists using cut-scores of T = 70 would seem to miss many students (but without diagnostic utility statistics the rate of correct classification remains unknown). You are warned, including by the BASC-3’s authors themselves, not to use scores alone to conclude a particular problem is either non-existent or that it is present.

Table 5.7 BASC-3 Parent Rating Scale Means and Standard Deviations for Selected Clinical Groups |

|||||

| All clinical groups | ADHD group only | ASD only | EBD only | Speech- language only | |

|

Selected BASC-3 PRS composites

|

|||||

| Externalizing | 58.1 (13.8) | 60.2 (12.7) | 55.4 (13.4) | 66.6 (16.1) | 50.7 (11.3) |

| Internalizing | 55.5 (12.3) | 55.1 (11.3) | 55.5 (12.6) | 64.0 (14.3) | 50.0 (10.7) |

| BSI | 60.5 (12.8) | 61.3 (11.6) | 63.3 (12.5) | 67.7 (13.8) | 51.9 (11.2) |

| Selected BASC-3 TRS composites (p. 161) | |||||

| Hyperactivity | 55.1 (12.3) | 56.5 (12.6) | 56.3 (11.5) | 58.4 (13.3) | 49.3 (10.5) |

| Attention Problems | 57.7 (10.3) | 59.3 (9.9) | 59.9 (9.3) | 57.6 (10.9) | 50.8 (10.3) |

| Anxiety | 56.9 (13.4) | 53.6 (12.8) | 59.4 (13.2) | 62.5 (14.2) | 52.6 (12.6) |

| Depression | 56.4 (13.4) | 53.8 (11.8) | 60.2 (14.1) | 63.9 (15.0) | 48.9 (8.5) |

| Bold indicates mean values falling in the “at risk” range (i.e., T-scores > 60). Source: BASC-3 manual p. 161 and p. 213. | |||||

You have heard a lot of talk in Chapter 2 about “probability” and the probability nomogram. Thus, it’s important to mention the term probability as used in the BASC-3 (e.g., the BASC-3 “Autism Probability Index).” This is a specialized scale whose scores are reported as T-scores. For reasons you learned about in Chapter 2 (e.g., base rate considerations), a score on this scale cannot indicate the probability that autism is present in your particular setting. The same is true for the “ADHD Probability Index” and the “EDB Probability Index.” As you saw above, the manual provides mean values for clinical groups on these scales, but it does not provide diagnostic utility statistics (and certainly not probability statements-how likely a particular student is to have a given condition). You are encouraged to examine Table 5.8 and to reflect on the numbers seen there.

| Table 5.8 BASC-3, various probability index scores and values for clinical sample | |||||

| All clinical groups | ADHD group only |

ASD only |

EBD only |

Speech- language only |

|

|

Teacher Report Scale (p. 161) |

|||||

| ADHD Probability Index | 57.8 (10.4) | 58.8 (10.3) | 60.6 (9.2) | 58.5 (11.5) | 50.9 (10.0) |

| EBD Probability Index | 56.2 (12.4) | 54.7 (11.3) | 58.6 (12.1) | 63.0 (15.0) | 50.0 (9.9) |

| Autism Probability Index | 58.0 (11.9) | 55.6 (10.0) | 66.7 (11.7) | 59.3 (11.1) | 50.6 (8.6) |

|

Parent Report Scale (p. 213) |

|||||

| ADHD Probability Index | 61.0 (10.8) | 64.4 (9.4) | 61.5 (10.0) | 62.7 (11.4) | 51.2 (10.1) |

| EDB Probability Index | 58.7 (13.1) | 59.5 (12.8) | 58.3 (11.4) | 68.2 (14.2) | 51.9 (10.8) |

| Autism Probability Index | 59.0 (13.2) | 56.8 (11.2) | 69.5 (14.6) | 61.1 (12.4) | 52.7 (11.0) |

|

Bold font denotes mean values that fall into the “at risk” range (i.e., T > 60).

ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; EDB = Emotional Behavior Disorder. Adapted from the BASC-3 manual (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015)

|

|||||

Additional Thoughts about Using the BASC-3’s

Scant evidence of classification validity notwithstanding, the BASC-3 enjoys diverse school psychology uses. This includes helping to decide if a mental health condition is present. Later in this chapter, Patrick O’Connor uses it routinely to avoid missing emotional problems as he conducts SLD-oriented evaluations. Novella Jones employs it as a center piece when she is referred a student with potential social-emotional problems. You will see other applications of the BASC-3 in Chapter 11 (concerning a student with potential autism) and Chapter 12 (concerning a student with potential ADHD). The case of Breanna in Chapter 7 demonstrates how BASC-3 results can help inform other assessment practices, in this instance a student interview. Skills Workbook exercises will also help you think about BASC-3 applications.

Conners Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scale (Conners CBRS)

The Conners CBRS (Conners, 2010) is one of several tools developed by a clinical psychologist named C. Keith Conners. His lengthy and influential career involved many aspects of assessment and intervention, including seminal research on ADHD (Stein & Newcorn, 2018). The Conners CBRS is described as “a comprehensive assessment tool that assesses a wide range of behavioral, emotional, social, and academic concerns and disorders in children and adolescents” (Conners, 2010, p. 1). It comprises options for teachers and parents to complete (discussed in this chapter) as well as for a youngster to complete himself (discussed in Chapter 6). Its age range is from 6 to 18 years. Thus, the Conners CBRS is applicable for most school referrals, but not those arising in early childhood education programs or sometimes in kindergarten. There is a separate version for preschoolers (the Conners Early Childhood, Conners, 2009). There is also the Conners-3 (Conners, 2009) for ADHD and related disorders, which is covered in Chapter 11. The nearly identical titles can prove confusing. In this chapter, however, it is just the teacher and parent report versions of the Conners CBRS (with the green manual cover) that are addressed. Research suggests that the Conners CBRS enjoys some use by school psychologists, but dramatically less than the BASC-3 (Benson, Floyd, Kranzler, Ekert, Fefer & Morgan, 2019). Still, some school psychologists adopt routine Conners CBRS use and consistently employ it over the BASC-3 and other competitors.

Like other broadband scales, the Conners CBRS requires little school psychologist time. The prime burden is scoring, and of course interpretation. Like most contemporary psychometric tools, however, automated scoring makes score generation quite easy and fast. Those wishing to use this instrument should first read its manual. A simplified guide prepared by Elizabeth Sparrow (2010) might also prove helpful. This chapter’s information is simply an orientation.

Conners CBRS Organization and Characteristics

The Conners CBRS (parent or teacher versions) comprises 203 or 204 items. These items provide information on more than 50 dimensions, addressing the following superordinate categories:

- Content scales

- DSM-IV-TR symptom scales

- Validity scales

- Index

- Other clinical scales

- Impairment items

- Critical items

- Additional questions

Table 5.9 summarizes details within a few of these broad categories. Some of the dimensions seem similar to those found on the BASC-3. And it is easy to envision how this array of scores might support those confronting a host of assessment situations. Like the BASC-3, the Conners CBRS includes validity scales and content scales, which are rather straightforward. There is also a global indicator (the 24-item Conners Clinical Index; Conners CI), which aims to categorize an individual child as more like a member of the general population than a child with a clinical diagnosis. In this sense, the Conners CI calls to mind the BASC-3’s BSI, but as you will read below that the two are actually quite distinct. We take a critical look at the Conners CI a few paragraphs below.

Table 5.9 Conners Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scale Content, DSM, Validity, Index, and Impairment Scales |

|

| Content scales | Emotional distress (upsetting thoughts, worrying, upsetting, thought/physical symptoms, social anxiety) |

| Defiant/aggressive behaviors | |

| Academic difficulties (language, math) | |

| Hyperactivity | |

| Hyperactivity/impulsivity | |

| Social problems | |

| Separation fears | |

| Perfectionism and compulsive behaviors | |

| Violence potential indicator | |

| Physical symptoms | |

|

DSM-IV-TR symptoms scales†

|

ADHD, predominately inattentive type |

| ADHD, predominately hyperactive-impulsive type | |

| Conduct disorder | |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | |

| Major depressive episode | |

| Manic episode | |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | |

| Separation anxiety disorder | |

| Social phobia | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | |

| Autism disorder | |

| Asperger’s disorder | |

| Validity scales | Positive impression |

| Negative impression | |

| Inconsistency index | |

| Impairment items | School work/grades |

| Friendship/relationship | |

| Home life | |

| †Allows both symptom count pertaining to DSM and calculation of T-score values (see p. 46) | |

The Conners CBRS manual helps guide score interpretation. Diagnosticians are advised to first check validity scales, then interpret scale scores (regarding content and DSM), then examine all indexes, such as those pertaining to impairment, as well as the Conners CI. They ultimately scrutinize fine-grained details, such as individual general items or those designated to be critical. As with the BASC-3, the first level of interpretation is largely nomothetic in nature. In contrast, latter item-level scrutiny (if it is used) might serve idiographic purposes.

The manual advises users to consult several sources of information rather than investing all of their trust in rating scale scores. And there are cases (e.g., Monty B. found in Chapter 8 of the Conners CBRS manual) that provide a bit a guidance about how this might be done. These include the familiar sources you saw in Chapter 1, review of school records, interview with family/caregivers, and student observation. Thus, one might logically conclude that the manual, at least implicitly, harmonizes with this book’s HR approach, as well as the sometimes-used probability nomogram.

The Conners CBRS and Classification Validity

Unlike the BASC-3, the Conner’s CBRS provides plenty of information about classification validity (referred to by the publisher as “discriminant validity”). Specifically, Chapter 12 of the manual provides extensive coverage of familiar diagnostic utility statistics. As is typical among broadband rating scales, a number of clinical samples were assessed to help establish evidence of validity. These include groups comprised of individuals with the following conditions:

- ADHD Inattentive

- ADHD Hyperactive-Impulsive

- ADHD Combined

- Disruptive Behavior Disorders

- Major Depressive Disorders

- Bipolar Disorder

- Anxiety Disorders

- Pervasive Developmental Disorders

The resulting data enable calculation of diagnostic utility statistics. For illustrative purposes, we look only at several Conners CBRS DSM-related symptom scales (see Table 5.10). But many other Conner’s CBRS scales were subject to analysis, and scores associated with those analyses are available in the manual. Information in Table 5.10 includes DLRs, which were calculated for our purposes and which might be plugged into the center column in a probability nomogram in practice. Although DSM-5 has now replaced DSM-IV-TR, the findings reported in the manual presumably still hold true.

Table 5.10 Effect Sizes and DLR Values for Conner CBRS DSM-related Scales Predicting Categorization in Clinical vs. Representative Samples |

||||

| Source of Rating | Effect size associated with positive score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Positive | Effect size associated with negative score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Negative |

| Teacher | ||||

| ADHD Hyperactivity-Impulsivity | Small | 2.9 | Minimal | .57 |

| ADHD Inattentive | Small | 3.0 | Small | .42 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Small | 4.8 | Small | .38 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | Moderate | 6.8 | Moderate | .20 |

| Autism | Moderate | 6.8 | Small | .28 |

| Parent | ||||

| ADHD Hyperactivity-Impulsivity | Moderate | 5.2 | Minimal | .53 |

| ADHD Inattentive | Small | 3.4 | Small | .41 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | Moderate | 5.0 | Minimal | .62 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | Moderate | 5.0 | Small | .35 |

| Autism | Moderate | 7.8 | Moderate | .16 |