8 Student Observations

Key takeaways for this chapter…

- Because school psychologists have access to students’ natural environment, they are afforded unique opportunities to observe

- In general, classroom and in-office observations support use of the HR process

- Classroom observations can be summarized numerically via commercially-produced tools (e.g., the BASC-3’s Behavior Observation System of Students) as well as many non-commercial options

- Classroom and in-office observations also can be accomplished with standardized, norm-referenced tools (e.g., the ASEBA’s Test Observation Form and Direct Observation Form)

- Their desirable ecological validity notwithstanding, direct observation procedures often lack evidence confirming their reliability and general validity

- Most observation procedures lack rules for making clinical decisions

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- Alex, disheveled

- Blair, meticulously groomed

- Caleb, scratched and scraped

- Destinee, thin with baggy clothing

- Shannon, out of her seat

- Romulus, ambiguous classroom anecdotes

- Remus, classroom anecdotes suggestive of ASD

- Justin Melrose, the substitution heuristic

- Sierra Snowden, a school psychologist who prefers her observation system

History’s very first psychological assessment technique probably consisted of a direct behavioral observation. This makes sense. After all, we humans have observed one another throughout our collective history, every single day, many, many times. We are finely honed to perceive person-to-person variations in body types, facial configurations, transitory facial expressions, mannerisms, linguistic habits, attire, and grooming, often entirely free of conscious awareness. Our perceptions of one another helped to quickly characterize co-inhabitants of our social world and in turn guide our own plans and actions. Among other things, social perceptions inform us about whom to trust, whom to avoid, and who might be a potential collaborator or even a potential mate. They spontaneously suggest to us who is typical and who is not. In this chapter, however, the process of observation is considered more deliberately, logically and scientifically. This chapter addresses various purposes and methods of observation that can be applied during the intentional practice of school-based social-emotional assessment.

Direct observations are enormously popular. Too frequently, however, school-based practitioners seem to end up conducting low-yield observations. Often, busy schedules afford only the briefest moment to plan an observation. There may not even be time for the school psychologist to familiarize herself with each classroom’s rules, an essential consideration in judging the meaning of a student’s behavior (Shapiro, 2010a). Similarly, school psychologists’ to-do lists, looming administrative timelines, and classroom calendars may preclude anything more than a single, brief observational interlude. What’s more, some school psychologists view observations as merely another box to be checked off in a long list of mandatory assessment elements. For example, a school psychologist is nearly finished with an SLD evaluation. In spite of this, she is obligated to visit the classroom during ongoing instruction and make note of the student’s behavior (see Table 8.1). In this school district, the IDEA observation requirement is delegated to the school psychologist. Note that she must do this even when her mind is largely made up about the nature and severity of a student’s problem (perhaps based on cognitive and achievement test scores).

One might logically ask what is to be gained under these circumstances by a perfunctory classroom observation? Probably quite little. Similarly, a school psychologist receives a referral about a student with adjustment problems (but not necessarily special education candidacy). Accordingly, she proceeds by watching the student at work in his classroom or observing him at leisure on the playground. But one might ask what is the purpose of these observations? What might be accomplished? And, more broadly, do first-hand observations actually add anything to an assessment process that might already be rich with information derived from rating scales and other sources?

Table 8.1 IDEA Stipulation Regarding Student “Observation” |

| (a) The public agency must ensure that the child is observed in the child’s learning environment (including the regular classroom setting) to document the child’s academic performance and behavior in the areas of difficulty.

(b) The group described in §300.306(a)(1), in determining whether a child has a specific learning disability, must decide to— (1) Use information from an observation in routine classroom instruction and monitoring of the child’s performance that was done before the child was referred for an evaluation; or (2) Have at least one member of the group described in §300.306(a)(1) conduct an observation of the child’s academic performance in the regular classroom after the child has been referred for an evaluation and parental consent, consistent with §300.300(a), is obtained. (c) In the case of a child of less than school age or out of school, a group member must observe the child in an environment appropriate for a child of that age. See the following link: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/d/300.310 |

Answers to these crucial questions would seem to hinge on the school psychologist’s approach. And, almost always, this book’s preferred approach is one that embraces logic and thoughtfulness, not mere intuition or blind habit. As you might suspect, observations can both help formulate hypotheses where none have previously existed or help confirm (or disconfirm) already existing hypotheses. Thus, observations discussed here are one element of a multi-step process aimed to answer referral questions (the HR approach you already learned about).

Not covered in this chapter are several other uses of observations appearing in the school psychology literature. Specifically, you will hear nothing here about observations to judge the quality of teacher-student interactions, although this is an important general topic for pedagogy (e.g., see Downer, Stuhlman, Schweig, Martinez & Ruzek, 2015). Likewise, you will not learn about observation techniques that might concern teachers’ instructional style (and perhaps, indirectly, teacher competence). In fact, school psychologists should be especially mindful of role boundaries when they observe a student receiving classroom instruction. For example, when viewing a student with classroom behavior problems, school psychologists should scrupulously avoid the role of school administrator. That is, they should never characterize a student’s problem as the result of teacher ineffectiveness. School administrators judge teacher competence; school psychologists do not. One of the beauties of school psychology practice is the opportunity to work collaboratively with teachers. The reality is, however, if teachers sense that you are present in their classroom to judge their instructional competence, then you risk violating the trust and subverting the openness on which collaboration inevitably depends. Don’t do it.

It is also worth mentioning here that observations are a central part of conducting functional behavioral analyses (FBAs). But FBAs constitute a specific set of procedures and a distinctive set of practitioner skills. FBA’s start with detailed observation procedures as a prelude to behaviorally-based intervention. It is essential to know when an FBA is the referral concern and to respond appropriately. FBA-related skills are extremely important. FBAs, however, are not covered in this book. Readers are strongly encouraged to visit more detailed sources regarding FBAs (e.g., Matson, 2012; Steege, Pratt, Wickerd, Guare & Watson, 2019).

Categories of Student Observations

This chapter reviews ways in which various categories of observation help answer standard social-emotional referral questions. In this chapter, you will learn more about:

- The child’s physical appearance as a clue to his genetic status

- The child’s physical appearance as a clue to his personality and mental health status

- Observations of the child during face-to-face testing

- Observations of the child in the natural environment (e.g., in classroom, on playground)

The rationale, advantages, and disadvantages of each observation endeavor are covered.

Physical Appearance as a Clue to Genetic Status

School psychologists generally conceive of themselves as either: (1.) behavioral scientists or (2.) as educators who possess specialized psychological knowledge and skills. Our discipline is not a biological or medical one. There are times, however, when every school psychologist’s practice inexorably brushes up against aspects of biology (and potentially medicine). One of these times takes place when school psychologists observe the physical appearance of students they are evaluating. In these instances, a prime concern is whether a student’s appearance is typical (unremarkable) or atypical (remarkable). This summary judgment depends principally on the presence or absence of signs of dysmorphology—observable congenital malformations. Most relevant malformations appear on the child’s head and face—improperly proportioned, over-or undersized heads, asymmetrical faces. And this is where school psychologists should direct their scrutiny.

Let’s take a step back to consider dysmorphology and why it might matter to all diagnosticians, including school psychologists. A well-accepted tenet of evolutionary psychology is that some facial configurations are universally viewed as attractive (i.e., across cultures and across millennia). A prime example is facial symmetry, which is an important marker of physical and reproductive health (Buss, 2009). In simple terms, faces that seem subjectively attractive to us are known to be objectively symmetrical; they can be documented to be relatively devoid of misshaped or misaligned features (e.g., eyes, ears). Using the same logic, the presence of conspicuous anomalies may denote prenatal problems (exposure to toxins, genetic errors) with the potential for wide reaching impact on health and development. What’s more, obvious anomalies of appearance are readily detected. For example, educators (even without any medical training) can reliably distinguish students who are outliers in terms of physical appearance (Salvia, Algozzine & Seare, 1977). For reasons like these, the field of medical genetics now routinely employs the notion of “dysmorphology.” Critically, the presence of dysmorphology is used to denote risk of underlying genetic conditions (e.g., single gene conditions like Down syndrome) or exposure to toxins (e.g., fetal alcohol spectrum disorder [FASD]).

One may wonder about the relevance to school psychology. Interestingly, Orme and Trapane (2013) prepared an journal article whose title poses this very question, “Dysmorphology: Why is it important to practicing psychologists?” These authors contend that dysmorphology’s importance lies in its ability to hint at the presence of a disorder with accompanying social-emotional and/or developmental risks (see Table 8.2 for examples). Consider the example of students with Williams syndrome, an autosomal dominant disorder. These individuals have high rates of social-emotional problems, with objective ratings surpassing, for example, children with Down syndrome (Cornish, Steele, Monterio, Karmiloff-Smith & Scerif, 2012). Critically for this argument, individuals with Williams syndrome also express recognizable characteristics of dysmorphology: broad forehead, short nose, full cheeks, and wide mouths. Considerations like this prompted the authors to assert: “just as psychologists routinely observe….dress and manner, they should also scan for minor anomalies” (Orme & Trapane, 2013, p. 401). This practice is already widespread in medicine. For those interested, the National Institutes of Health has a link that concerns the terminology related to human malformations (and many, many photos depicting dysmorphology). School psychologists themselves, however, would not generally be expected to describe any features in such fine detail as found on the website. https://elementsofmorphology.nih.gov/index.cgi.

As you already probably know, children with Down syndrome, for example, are quite readily recognized. Children with other syndromes and other dysmorphic appearances may turn out to be far less obvious. Children with two recognizable syndromes are depicted in Figure 8.1 and 8.2. Readers should ask themselves whether they might not view each of these youngsters as appearing atypical, even if it would be difficult to describe the exact characteristic-by-characteristic departure from typical appearance. Not surprisingly, clinical applications of dysmorphology have been empirically investigated. For example, Flor, Ballando, Lopez and Shui (2017) devised an Autism Dysmorphology Measure (ADM) to help make predictions about underlying problems among some children with autism. They tapped the physical attributes of head size as well as several body regions (i.e., stature, hair growth pattern, ears, nose, face size and its structure, philthrum [the vertical indentation in the center of the upper lip], mouth and lips, teeth, hands, fingers, as well as nails and teeth). ADM scores were found to possess good sensitivity and specificity in distinguishing “complex” from “essential” cases of ASD. The former group of children might require referral on to a medical geneticist or require treatment not warranted for an “essential” autism counterpart.

To be clear, however, this was a study possessing relevance primarily for physicians. And also to be clear, no one is telling school psychologists to conduct detailed physical evaluations (comparable to a physician using the ADM). Nonetheless, it is argued that school psychologists ought to scan every student for blatant indications of unusual physical presentation. To this point, in an article prepared expressly for school psychologists, Wodrich and Kaplan (2006) listed dysmorphology as one of five “red flags” that ought to prompt consideration of a referral to a medical specialist. According to Wodrich (a psychologist) and Kaplan (a neurologist) the goal is not to articulate any exact physical anomaly nor to guess about any particular syndrome. Rather, the school psychologist’s task is simply to notice and report the obvious. You will see more about dysmorphology in Chapter 12, where observations of dysmorphology are shown to matter in cases of potential autism.

Table 8.2 Syndromes, Physical Features and Social-Emotional Risk |

||

|

Condition |

Physical signs |

Social-emotional risks |

| Angelman syndrome | Small head, poor muscle tone, coarse facial features | Excitable demeanor, hand flapping, hyperactivity, language impairment and developmental delay |

| Fragile X syndrome | Narrow face, large head, large ears | Anxiety, ADHD, autism spectrum |

| Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder | Small eyes, smooth philtrum and thin upper lip, early growth delays | Hyperactivity, cognitive and language delays |

| Klinefelter syndrome | Tall, missing secondary male sex characteristics (males only) | Language problems, social difficulties, anxiety |

| Neurofibromatosis-1 | Skin lesions, changes in skin coloration, unusual iris | ADHD, learning disabilities |

| Prader-Willi syndrome | Narrow forehead, almond-shaped eyes, triangular mouth, obesity | Ravenous appetite, developmental delay, temper outbursts, stubbornness |

| Turner syndrome | Short stature, webbed neck, lack of secondary female sex characteristics (females only) | Learning problems (in math) and visual-spatial deficits |

| Tuberous sclerosis complex | Skin lesions | Hyperactivity, aggression, developmental delay |

| Williams syndrome | broad forehead, short nose, full cheeks, and wide mouths | ADHD, anxiety disorders |

| Source: NIH, Genetics Home Reference; NIH, Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center | ||

But what about those instances when a syndrome has already been established before contact with a school psychologist (e.g., via workup at a genetics clinic)? As you might suspect, there are important syndrome-to-syndrome variations in social-emotional risk, and these are sometimes documented by researchers using familiar rating scales. Children with Down syndrome as one example, were found to have no mean Conners CBRS (parent) DSM symptom score above T = 70. But children with fetal alcohol exposure (FAE), as another example, had much different Conners CBRS (parent) mean scores. This latter clinical group was found to have nearly every DSM-related score (from ADHD to Major Depression to Autism) elevated above T-score = 70 (Way & Rojahn, 2012). In other words, psychologically and educationally, syndrome membership often matters. In fact, in this study the presence of FAE might be thought of as changing the base rate of psychiatric problems. You can see how important this information might prove for school psychologists seeking to establish a student’s probability of a mental health disorder.

Physical Appearance as a Clue to Personality and Mental Health Status

Physical appearance can hint at aspects of personality and mental health status, not just potential genetic syndromes. Face-to-face encounters (such as while testing or during a child interview) afford the simplest method of observation. The rationale here is that hypotheses (such as covered in Chapter 2) are sometimes formulated, at other times strengthened, and at still other times weakened, by nothing more sophisticated than various aspects of a student’s appearance. Consider some of the following observations and, in parentheses, what each might imply:

- Alex is a disheveled third-grader with soiled clothing and body odor (perhaps he resides in a home characterized by limited resources and insufficient parental attention).

- Blair is a sixth-grade student with meticulous grooming and attire (perhaps she harbors obsessive-compulsive tendencies).

- Caleb is a six-year-old student with scabs and scratches on his face as well as his hands (he might be a daredevil who loves rough play and taking risks).

- Destinee is an extremely thin high school student wearing particularly baggy clothing (this might suggest an eating disorder).

Straightforward observations like these may prompt instant inferences. Some of these appear virtually unbidden, especially among veteran school psychologists. But even novice school psychologists might sense possibilities embedded in each of these observational vignettes. To assure thoroughness, however, it is generally wise to work systematically and invoke use of the Reflective System of thinking. For example, instead of noting one or two salient aspects of the child’s appearance and ignoring other dimensions, school psychologists might routinely scrutinize several important dimensions. They might, as seen in Chapter 2, follow a simple checklist to guarantee that each dimension was actually considered. The school psychologist would ultimately summarize any area deemed important, but only after considering all dimensions. Suhr (2015) lists 10 dimensions potentially worth consideration in every case.

- Clothing

- Grooming/hygiene

- Posture

- Gait (i.e., walking)

- Motor movements

- Speech

- Facial expression

- Eye contact

- Level of attention/alertness/arousal

- Need for repetition

If you are just starting to learn how to make and report observations, a checklist is advised. Although potentially helpful, observations of these dimensions (and making inferences about what was seen) is not a risk-free process. As you might suspect, observation-based inferences are best treated as possibilities that are unavoidably speculative. This is true, in part, because research to buttress the validity of such inferences is generally lacking. Consequently, there would seem to be a distinct risk of false positives any time diagnosticians attempt to draw conclusions from scant observations.

You might infer that Desiree’s presentations signals an eating disorder but inferences like this one will often prove to be wrong. In fact, even the reliability of direct observations (e.g., of things like attire and grooming) might also be questioned. Perhaps disheveled-appearing Alex is generally well-groomed, but you caught him on a day when a family emergency disrupted routine parental supervision of activities of daily living (e.g., shower, change of clothing). To the same point, Caleb’s customary style of play might actually be moderately cautious, but you saw him after an uncustomary skateboard ride left him battered. Snapshot observations may actually represent extremely unreliable indicators of any aspect of personalities of either Alex or Caleb. Then again, observations like the four mentioned above should probably not be summarily disregarded. Maybe Caleb’s facial scrapes are sufficient to prompt questions about emergency room visits. If his mother indicates that Caleb has needed three trips to the ER for play-related injuries, then mandatory questions about poor appreciation of danger, specifically, and impulsivity, generally, would make sense. School psychologists are urged to stop and think (use the Reflective System) about the evidence before them and reason about how to treat it in their ongoing conceptualization of each student.

Observation During Psychometric Testing

When routine psychoeducational evaluations are conducted, school psychologists nearly always report on the student’s behavior. One reason for doing so is to verify that cooperation and effort during testing were sufficient to infer valid test administration. Another reason, however, is to enable elementary inferences about the child’s social-emotional status. As you may already know, the IDEA definition of specific learning disability (SLD) indicates that SLD is ruled in only when emotional disturbance (ED) is ruled out. Thus, observations during cognitive and achievement testing are important for quasi-legal reasons; if something is witnessed that might imply the presence of an emotional disturbance, rather than an SLD, this fact should be reported. Conversely, if nothing indicative of social-emotional problems is witnessed, that fact too should be reported (see Table 8.3 for a summary of a student’s behavior during a psychoeducational evaluation). This makes observations during testing the equivalent of a social-emotional screening process. Beyond special education considerations, however, behavior during testing should be reported for professional reasons. School psychologists should not miss any indication of a potential emotional problem (or of emotional health), even if the referral question concerns academics, not behavior or adjustment.

Table 8.3 Informal Observations Made during a Student’s Psychoeducational Evaluation |

|

| Adapted from Sattler (2014) |

School psychologists’ observations made during testing are often described informally. For example, a student can be described according to common terms, such as found in Sattler’s classic text (2014). Adjectives such as enthusiastic, cooperative, hardworking, conscientious, focused or disinterested, uncooperative, lackadaisical, indifferent, inattentive all convey personality elements able to generate (or help to strengthen or weaken) hypotheses. Helpful sources include Braaten’s (2007) book on report writing, which is loaded with adjectives that psychologists might use to describe students. Even more helpful, Braaten’s list of adjectives is organized on a continuum, which helps psychologists consider and then write clearly about students.

The prospect of errors of diagnostic decision making (e.g., springing from confirmation bias or the availability heuristic) is a recurrent theme of this book. So is the idea that structure surrounding decision making, such as using checklists, can help ameliorate these risks by slowing thinking. Happily, there is a powerful objective complement (or alternative) to informal test-related observation practices. This is the Test Observation Form (TOF; McConaughy & Achenbach, 2004). The TOF is a checklist completed by examiners after they have finished their testing session(s) with a student. The TOFs 125 Likert-scale items correspond to those on the Child Behavior Checklist. In other words, the TOF is in some ways an examiner-completed variant of the Child Behavior Checklist; both are part of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) that you read about in Chapter 5. Accordingly, there are TOF standard scores available for children 2 to 18 years. There is also research. For example, observation-related scores derived from the TOF after students completed IQ and achievement testing were successful in helping to correctly classify students. Specifically, 177 6- to 11-year-olds with ADHD predominately combined type; ADHD predominately inattentive type; a clinical sample without ADHD, and normal controls were largely correctly classified based on TOF scores (McConaughy, Ivanova, Antschel & Eiraldi, 2009).

Interestingly, the TOF was developed largely for use by school psychologists for routine completion after they had finished cognitive and achievement testing (personal communication, T. M Achenbach, January 8, 2020). It’s obvious positives and its authors hope for its use aside, the TOF seems to have garnered relatively little use in schools. Many practicing school psychologists, as well as university-based school psychology trainers, express surprise to learn that there is a ASEBA Child Behavior Checklist alternative suited to tapping students’ social-emotional during psychometric testing. At present, there is only a hand-scoring option of the TOF, although the relatively few steps needed to exercise this option seem easy to accomplish and fairly quick to complete.

Observation in the Classroom (Natural Setting)

School psychologists are blessed with opportunities to observe students in their natural environment. In contrast, our clinic-based colleagues (psychologists, psychiatrists, pediatricians) must depend on what stakeholders (and the children themselves) tell them, buttressed only by their own observations in the artificial environment of an office or clinic. Observations of students in their real world are said to enjoy “ecological validity.” If there is a concern, for example, that a student fails to follow classroom rules, then a good test of that assertion is to observe him during class and find out if rule breaking is actually witnessed. The ecology of each class is unique; observing without that ecology is fraught with potential error. In fact, when school psychologists skip on-campus observations, they encounter the very same limitations of their clinic-based counterparts.

Before school psychologists engage in classroom observations, however, they are urged to reflect on their role. As a school psychologist, you are not there to observe and comment on the effectiveness of a teacher. This is true although teachers’ positive actions and the frequency of those actions are known to affect student performance and alter student behavior (Reddy, Fabiano, Dudek & Hsu, 2013; Reinke, Herman & Newcomer, 2016). School psychologists are also advised to reflect on each case’s specific observational need. For example, although classroom observations might determine whether a student is improving with implementation of a classroom behavioral plan, this type of observation addresses a quite specialized concern (i.e., monitoring a student’s progress). Chapter 15 concerns just this delimited reason for making classroom observations. Critically, however, measuring progress reflects a mission different from observation intended to draw general conclusions about the presence, intensity, and nature of a social-emotional problem (Ferguson, Briesch, Volpe & Daniels, 2012). Some school psychologists, especially those who practice behavioral consultation, routinely observe for the former purpose (i.e., to monitor progress). Be sure to reread your referral question before you observe and remain fully cognizant of your purpose. Your observational technique should follow logically from your purpose.

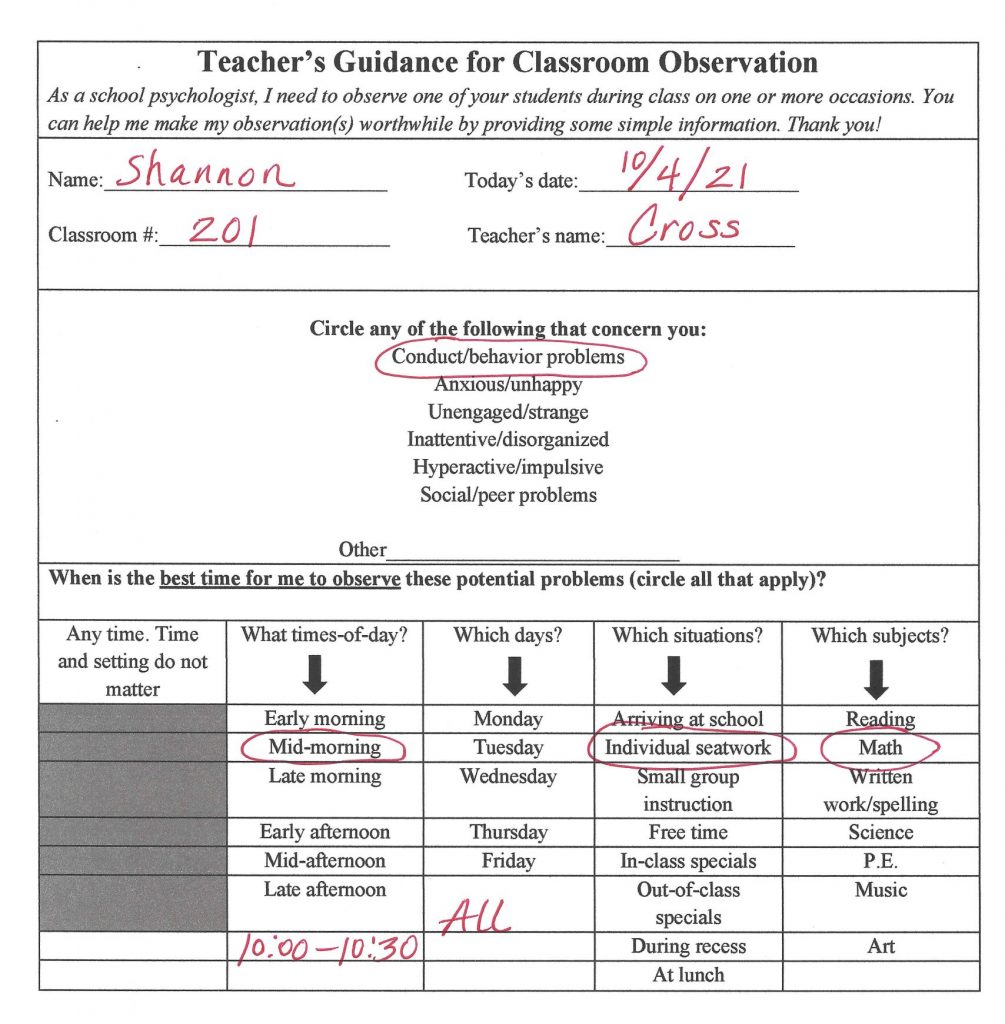

Once the requirement for a natural-setting observation is apparent, you confront some challenges. A first challenge is developing a plan that maximizes your prospect of actually seeing pertinent behavior. For example, a teacher expresses concern that one of her students, Shannon, is non-compliant and argumentative. You already possess some ways (e.g., interview, rating scales) to determine the veracity of the teacher’s contention and to judge whether it is the prime (or singular) problem or just one aspect of more pervasive social-emotional difficulties. But you want to see the behavior for yourself. Observing non-compliance or argumentativeness can help judge its intensity (nomothetic) and the contextual variables surrounding its expression (idiographic). Observations can also help assure that informants are not mischaracterizing a student’s actions. Perhaps her teacher describes Shannon’s actions as defiant and confrontational, whereas your observations might suggest something more benign and less uncommon. Consider the following exchange.

- School psychologist: “So, I noticed Shannon left her seat during arithmetic to get a tissue. I saw that she was pretty slow to go back to her desk. When you told her to get back to her work, she replied ‘Just a minute.’ Is that what you are talking about when you describe her as defiant and confrontational?”

- Teacher: “Yes. That’s pretty typical. Sometimes she has an angry tone, she didn’t today, but sometimes she does.”

You might hypothesize even from this singular observation/dialogue snippet that this teacher’s description of Shannon’s actions (and similarly her representations of Shannon on rating scales) is slanted toward the negative. Classroom observations sometimes enable this kind of discovery that might never arise from teacher interviewing or rating scales.

But practically, when should you visit class (or somewhere else on campus) so that you have a realistic chance of seeing Shannon’s problematic behavior? Figure 8.3 is designed to help you manage this challenge. Eliciting information like this (i.e., when to observe, what to look for) from a teacher simply allows a school psychologist to narrow down when and where problem behavior might be seen. Alternatively, you might just talk with the teacher to get his sense about a good time to catch the behavior of concern.

A second, related challenge, is observing often enough (and long enough) to view the behavior of concern. Many school psychologists are so busy that they can schedule just a single observation session, perhaps lasting only 10 minutes. There is a distinct danger that a single 10-minute observation session fails to capture behavior that is representative of the student over time. Consider the reality that many students attend class for 750 minutes during just one week. A 10-minute observation samples a mere 1% of the student’s school behavior for that week. In one of the sections that follows, you will read about empirical research concerning the requisite number of observations to make decisions about students.

A third, somewhat related, challenge to natural-setting observations is avoiding so-called “reactive effects” (sometimes simply referred to as “reactivity;” Briesch, Volpe & Floyd, 2018). Reactive effects concern alterations in a student’s actions because she is being observed. For example, Shannon’s routine acting out during free time might be curtailed (or exaggerated) simply because she recognizes that an outsider is now present in class (and is seemingly there to look at her). Thus, it is often helpful to select an inconspicuous location near the back of the classroom, to avoid staring at the target student, and to conduct observation(s) early in the sequence of assessments (so the student is less cognizant of your role). School psychologists and teachers must also decide what to tell the student. Some school psychologists (or classroom teachers) inform students beforehand that they will be observed. Others do not, fearing that advanced notice will inflate the risk of reactive effects.

A fourth challenge is the threat of confirmation bias. Working hypotheses, such as Shannon has oppositional defiant disorder, are appropriate and helpful (as argued in Chapter 2). Hypotheses arise automatically when school psychologists engage a step-by-step assessment process (e.g., use the HR approach). But hypotheses can also encourage blinders, directing observers toward students’ actions that confirm extant hypotheses and away from actions compatible with other (potentially equally plausible) hypotheses. For example, Shannon’s school psychologist might be especially vigilant of any deed that implies non-compliance while disregarding instances of cooperation and rule following. Focused solely on Shannon, the school psychologist might fail to notice that many other (non-referred) students express comparable levels of non-compliance. Confirmation bias may also promote disregard for signs of anxiety. Perhaps Shannon bites her nails, struggles to speak when called on, or avoids anxiety-provoking novelty, all of which risk being overlooked in a world where an observer has a nose for compliance problems but little else. To remind you, the threat of confirmation bias is mitigated by structured procedures and checklists. Structure helps insure that Reflective Thinking supersedes humans’ hardwired preference for Automatic Thinking.

Types of Observation Strategies

Anecdotal Observations in Class

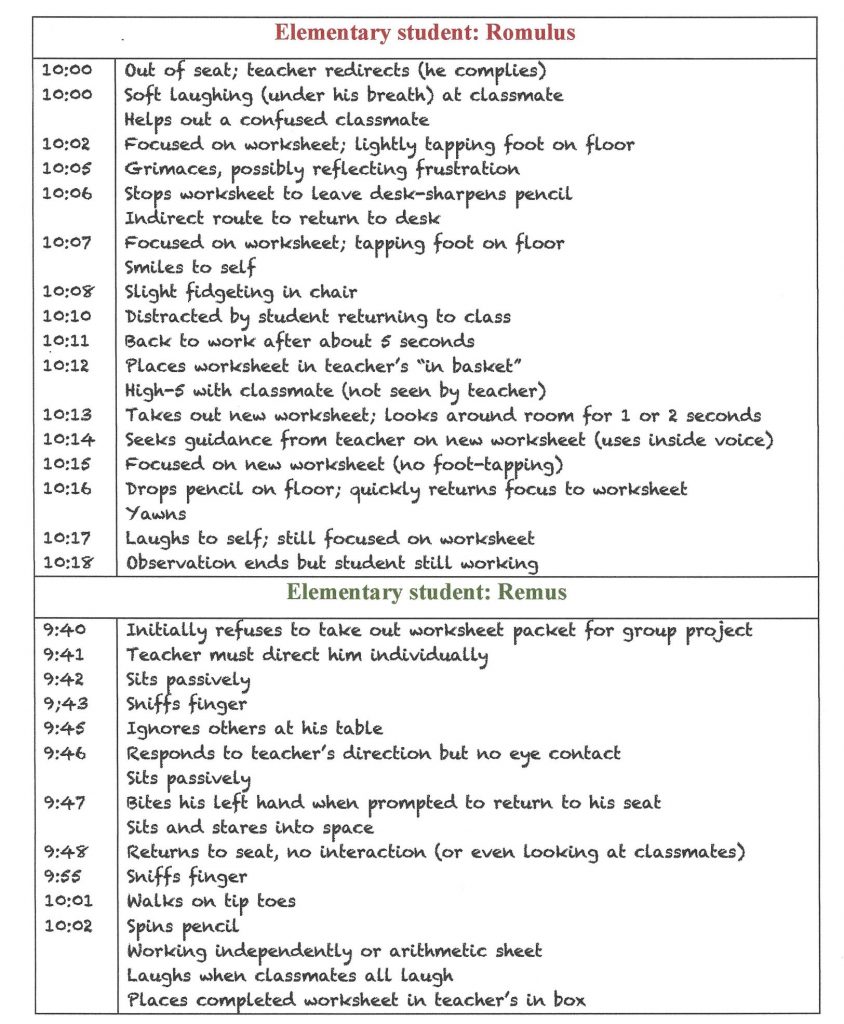

Anecdotal observations (or more accurately, observations that result in anecdotes) consist simply of watching and recording. Snippets of behavior are recorded, usually without the observer attempting to infer the child’s motives. Written anecdotes in turn fuel inference making. Figure 8.4 illustrates notes from an anecdotal observation of two elementary students made during seatwork. If you read the notes concerning Romulus, the first example, conjecture and conclusions may come to mind, or they may not. Are the notes about Romulus describing a problem-free student? One with attention problems. A moody-unhappy child? A non-compliant one? A disengaged student who doesn’t care about school or academics? It’s not entirely clear which of these inferences is most plausible, although some interpretations seem much less credible than others. The anecdotes recorded for Romulus are like those recorded for a great many students. They are arguably a bit of a Rorschach. The observer risks projecting her own prior beliefs and expectations into her recordings as well as into her subsequent analysis of her notes. This is true because none of the behaviors witnessed for Romulus is likely to have particularly strong diagnostic value. For example, how diagnostic is an observation of “out-of-seat behavior” for conditions like ADHD? Witnessing one or two out-of-seat instances per 15-minute observation session so as to infer the presence of ADHD would seemingly lead to many false positives. The informal, unstandardized, non-normative bases of anecdotal observations can represent a troubling limitation.

Even though this is true concerning Romulus, now consider the second set of observations found in Figure 8.4, which concern Remus. Are these describing a problem-free student? They probably are not. Whereas being out-of-seat a couple times in Romulus’s case may not be indicative of anything, biting one’s self, repetitive finger sniffing, toe walking, hand flapping, and potential social disengagement suggest something noteworthy. To many diagnosticians, Remus’s actions imply low-frequency (rare) occurrences signaling the possibility of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Thus, the yield from direct observation seems far greater for Remus than Romulus. Even in the example of Remus, however, the drawbacks inherent in anecdotal observations are unescapable. The sensitivity of observation-derived instances of hand flapping and toe walking (% of times present in young children with ASD) and specificity (% of times absent in young children without ASD) are simply unknown. Lack of norms and no objective criteria to operationalize the behaviors observed makes drawing inferences from anecdotes a seat-of-the-pants enterprise.

As with most aspects of practice, planning can improve quality. Unfortunately, however, it seems that too often anecdotal observations occur without much prior planning. The school psychologist simply sits in during a class session and then watches to see what (if anything) becomes obvious. As you have already learned, however, assessment often unfolds in stages that consist of active hypothesis formulation, rejection, revision and affirmation. In the case of Romulus, for example, competing pre-observation hypotheses might include ODD vs. no real psychological problem (i.e., excessive concern by parent or teacher). Consequently, rather than merely jotting down observations as they arise, the school psychologist might be better off by preparing a case-specific observation template. In the case of Romulus, this might consist of a list of symptoms for ODD. Page 462 of DSM-5 lists criteria, and the school psychologist might list these on her otherwise-blank observation sheet before heading off to make her classroom visit. That is, she might be especially vigilant for the hallmarks of ODD as she observes Romulus: temper problems, touchiness, anger, argumentativeness, defiance, peer annoyance, blame shifting, and vindictiveness. This means that her observations are both broadly focused to detect possibilities not yet considered on the one hand and narrowly focused (to minimize the risk of missing any observations of ODD symptoms, her prime hypothesis) on the other hand.

Parallel considerations might exist regarding Remus’s observation. In his case, however, ASD might be the prime working hypothesis. Thus, the school psychologist might visit page 50 in DSM-5 and jot down the list of ASD symptoms: deficits in social reciprocity, impaired nonverbal communication, underdeveloped social relationships, stereotypies, adherence to routines, restricted interests, hypo- or hypersensitivity. Some of these symptoms may be obvious to any school psychologist even when operating without a preset plan (as reflected in the simple anecdotal observations in Illustration 8.1). But a list of target behaviors warranting special vigilance helps to assure that important anecdotes do not go unobserved. As argued earlier, human memory is imperfect. Creating simple lists can circumvent memory glitches. What’s more, such unfortunate memory failings can afflict even seasoned and skilled practitioners (see Gawande, 2009).

Structured (Commercial) Classroom Observation Procedures

There are structured alternatives to simple the recording of anecdotes. School psychologists should know about them; they should probably use them more often than they do. It’s true that structured procedures may seem more burdensome than simply writing anecdotes, but the yield is probably worth the extra time and effort.

One structured option is the Student Observation System (SOS) from the Behavior Assessment System for Children-3 (BASC-3; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015). You will recognize the BASC-3’s TRS, PRS, and SRP from Chapters 5 and 6. Happily, the BASC-3 also includes the SOS (covered in the very same manual). The two essential parts of the SOS have the advantage of providing structure, which might diminish confirmation bias and enhance validity by assuring that an array of diverse behaviors are systematically considered. The authors, quite correctly, advise prospective users to read Chapter 6 in the BASC-3 manual (it is just seven pages long) before proceeding. The SOS’s Part A (“Behavior Key and Checklist”) is comprised of 71 behaviors distributed across 14 categories. Four of these 14 categories are deemed “positive behaviors” (e.g., response to teacher/lesson, work on school subjects). In contrast, 10 of these 14 categories of behavior are deemed “problem behaviors” (e.g., inappropriate movement, aggression). Fine-grained distinctions are made within both positive behaviors and problem behaviors categories (e.g., response to teacher/lesson includes sub-distinctions such as “interacting with teacher in class/group” and “standing at teacher’s desk”; sub-distinctions related to aggression include “kicking others” and “pushing others”). It takes practice to be able to quickly recognize which narrow descriptions fall under which broader category.

Each SOS session consists of 15-minutes spent in the student’s classroom. At the end of 15 minutes, the observer marks each of the 71 Part A behaviors as “not observed,” “sometimes observed,” or “frequently observed.” But these terms are not defined. In addition, the observer estimates whether any of the checked behaviors were disruptive. SOS’s Part B is a structured time sampling method. It involves repeated brief observation intervals (each lasting 3 seconds). Following the 3-second window of observation, the observer has 27 seconds to check-off any of 71 behaviors discussed in the SOS Part A. Thus, the SOS Part B is a variant of popular methods used to quantify student engagement (attending and working). In fact, the SOS exemplifies the “partial interval” option described in detail below. As many school psychologists discover during their first use of the SOS, execution is less simple than may appear on the surface. Practice is needed. Also, it is worth remembering that there are no norms. In light of this fact, school psychologists may choose to observe two or three randomly selected classmates using Part B of the SOS. In fact, the BASC-3 manual seems to welcome peer observations like this.

Part B can also prove tricky. For example, Part B’s requirement to observe for 3 seconds and then record for 27 seconds requires splitting the observer’s attention between two tasks. That is, she must monitor elapsing time while simultaneously observing the student for the appearance of any of a very long list of actions. For reliability reasons, the observation interval should be precisely 3 seconds, not 1 or 2 seconds, and not 4, 5, or 6 seconds. But if the observer’s gaze rests on a stopwatch, then it proves impossible to closely watch the student. The solution is to prepare an audio file that parses time into 3-second observation intervals and 27-second recording intervals. A detailed description for preparing this tool appears in a research article by Winsler and Wallace (2002); the same technique is proposed for clinicians in schools (e.g., Shapiro, 2010a). The auditory nature of the file allows the observer to wear an earphone and keep her eyes on the child for the entire 3 seconds of observation. Another SOS Part B challenge is that the 14 categories (and 71 items) often seem too numerous to scan and mark during a 27-second recording interval, at least without considerable practice. Consequently, training and practice seem to be needed to guarantee proper SOS use. Yet another option is to use an electronic version of the SOS, but practice with this option would also seem necessary.

A popular alternative to the SOS is the Behavioral Observation of Students in Schools (BOSS; Shapiro, 2010a). The BOSS is in some ways similar to the SOS Part B but less elaborate (and easier to learn). The BOSS has nothing akin to the SOS Part A. Plus, the BOSS affords another major advantage—it’s free after initial purchase of the workbook in which reproducible BOSS forms are located (Shapiro, 2010b). The BOSS is barebones. It comprises just two positive behaviors (i.e., active engagement and passive engagement), plus three off-task variants (i.e., verbal, motor, and passive). Students are observed during one or more 15-minute sessions. During each session, the student is observed, and findings recorded for 48 intervals. The BOSS uses momentary time sampling (a snapshot determination made every 15 seconds for recording whether the student was on-task). It also uses a partial interval procedure regarding any of the off-task variants occurrence. Importantly, Shapiro also described the notion of “comparison peer.” While the target student is observed for 48 intervals, 12 intervals within the same overall session are devoted to observations of a comparison peer. In the absence of norms, the comparison peer’s score provides an anchor for interpretation (making the process of observations somewhat nomothetic in nature). This issue is revisited under the topic of cut-scores in a few pages. Obviously, the BOSS concerns a much more restricted array of behaviors and consequently would be valuable only in the presence of selected emergent hypotheses. For example, if there are questions about focus and task persistence (ADHD), the BOSS might be an appropriate tool. The same might be true for monitoring progress (see Chapter 15). In contrast, if there are questions about mood or unusual behavior, the BOSS would seem to represent a poorer choice.

Another structured commercial option is the Direct Observation Form (DOF). However, in some ways, this option is drastically different in style and usage from both the SOS and BOSS. This is because the DOF is part of the extensive ASEBA family of tools (McConaughy & Achenbach, 2009), which notably includes the Child Behavior Checklist. Much like the SOS, the DOF comprises two parts. One part of the DOF is an orchestrated time sampling procedure (reminiscent of the SOS Part B). It consists of a 10-minute observation session. For each 10-minute session, the observer records (dichotomously) “on-task” or “off-task” as witnessed during the final 5-seconds of each of 10 intervals. Thus, the percentage of “on-task” ranges from 0% to 100% (in 10% increments) during each observation session. Unlike on the SOS, DOF users write a brief narrative of any problem behavior evident during the interval. Also somewhat like the SOS Part B, the observer is directed back to a symptom list of 89 behaviors. But here is where the SOS (and BOSS) and the DOF part company: DOF items are on a 4-point Likert scale, the items match those on ASEBA CBCL, and TOF (listed above). Even more distinctively, the DOF produces norm-referenced standard scores. Importantly, these considerations mean that score profiles on the DOF fit hand-and-glove with the score profiles from the entire suite of ASEBA score profiles (e.g., CBCL). It is critical to note the following: the TOF is a nomothetically-oriented. When hypotheses involve classification (such as DSM-5 categories) the TOF would seem to hold advantages over idiographically-oriented procedures that lack norms.

In a now dated but still relevant article, McConaughy and Achenbach (1989) showed how the TOF could be integrated with other more familiar ASEBA tools to address a prime concern of school psychologists, determination of emotional disturbance. This topic is covered extensively in Chapter 10. But via a case example, these authors provide concrete practices about the TOF (e.g., how to conduct multiple observations with the TOF spanning over multiple days; the need to conduct observations in the regular classroom because the TOF norming process used this setting). Equally important, there is an explanation of how to integrate TOF scores with those from teacher and parent completed rating scales (i.e., CBCL and TRF) to formulate conclusions.

McConaughy and Achenbach (2009; 1989) warned users to complete multiple observations using the DOF. Just how many might be needed to produce reliable and valid scores was the subject of an important and sobering study conducted by Volpe, McConaughy and Hintze (2009). These researchers conducted up to 20 observations using the DOF. To reach what the authors referred to as acceptable levels of “dependability” and “generalizability” surprisingly many observations were required. For example, regarding the DOF Total Problems (a composite index) four observations were needed, but for the scales tapping Sluggish Cognitive Tempo and Inattention 11 and 14 observations, respectively, were needed! This research is yet another signal to school psychologists that they ought to practice with restraint and free of knee-jerk judgments. It’s hard to conclude much from a single classroom observation.

Structured (Non-commercial) Classroom Observation Procedures

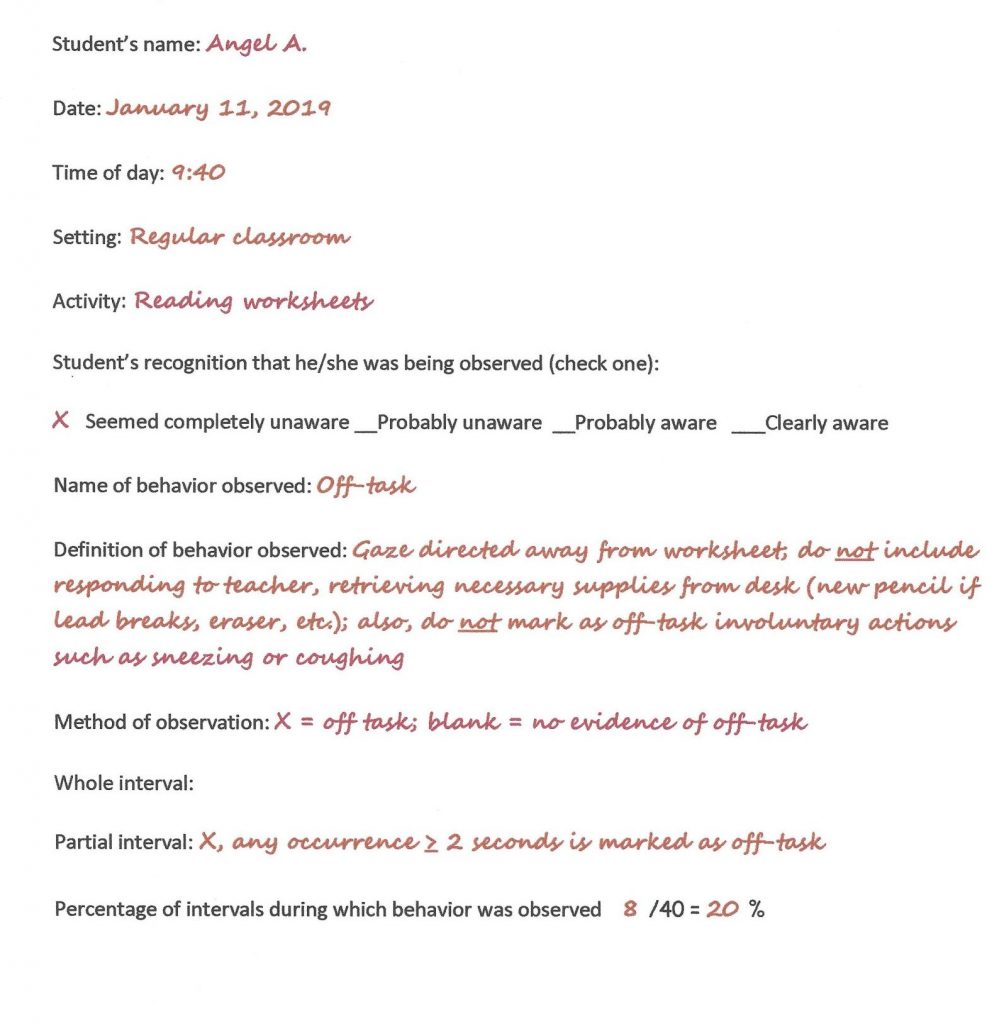

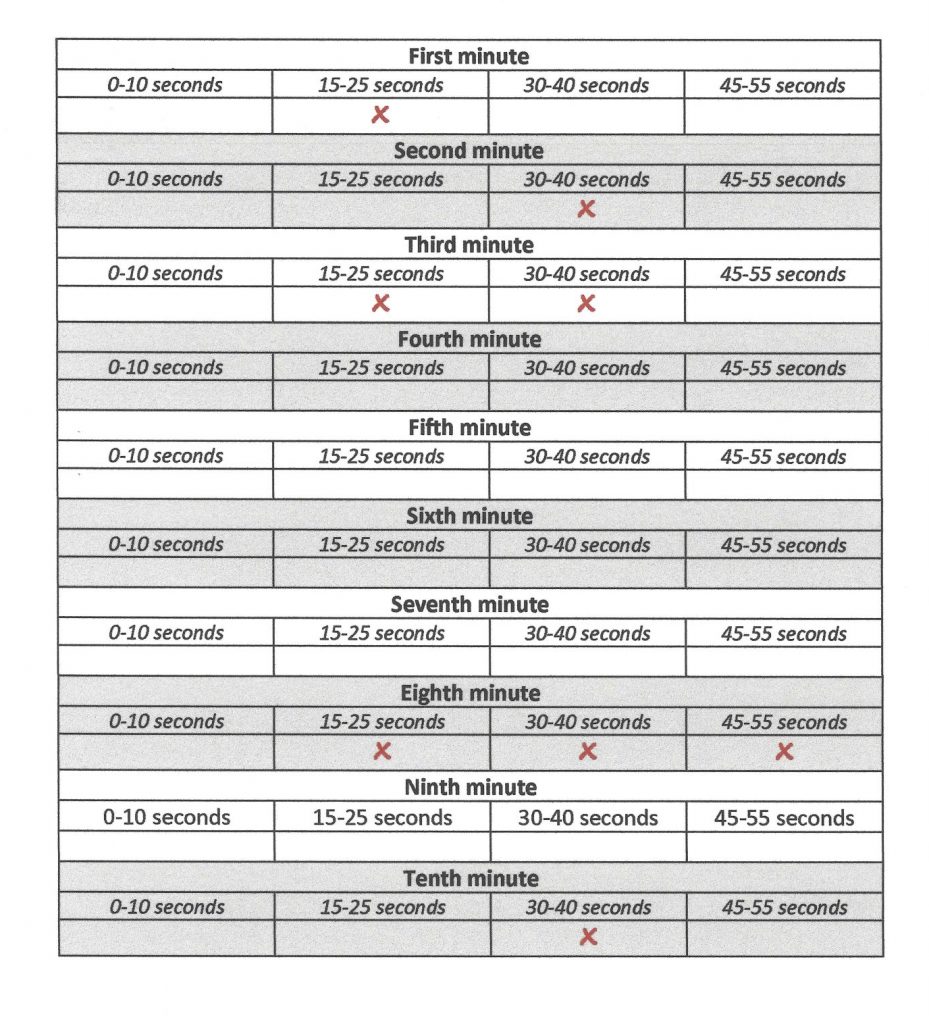

Another option for school psychologists is to simply construct their own time sampling forms. This may save money and simultaneously result in enhanced alignment with each clinicians’ stylistic and professional preferences. Home-grown scales, nonetheless, impose a degree of upfront work. For example, observers must decide how to treat behavior observed during each fixed interval. Sierra Snowdon, an independent-thinking school psychologist, decides to devise an observation form to help her make judgments about the presence of ADHD (her home state has recently authorized school psychologists to diagnose ADHD and sign off for OHI eligibility; see Chapter 12 for considerations about ADHD in schools). Her form will consist of four observation intervals each minute (see Figure 8.5 and Figure 8.6). Each interval lasts ten seconds; there is a five second interval during which Sierra will mark the behavior that she just witnessed. Here is Sierra’s dilemma. How should she actually (specifically) record student behavior:

- at only one moment in time (momentary time sampling; MTS)

- any occurrence of a behavior that occurs during a part of observation interval (partial interval recording; PTR)

- or behavior that is present during a whole interval of recording (whole interval recording; WIR)?

A related concern is how should the behavior under observation be identified. Should it be specified to concern “off-task behavior,” “on-task behavior,” “restlessness,” “out-of-seat behavior?” Any of these classes of behavior might help document problems akin to ADHD. But they are not all equivalent, nor are they all equally readily defined and faithfully observed.

Sierra has another challenge. That is how to define the behavior to be observed in a manner to promote reliability. In other words, she needs a definition that permits her observations during the beginning of a session to match those at its conclusion (or to assure that the criteria she uses for a first observation session are the same criteria she would use if she conducted a second observation session). To help maximize reliability, Sierra might turn to a standard prescription for defining behavior objectively. According to Alan Kazdin, one of the giants of applied behavior analysis, definitions of behavior should contain three elements. These are: (1.) objectivity, (2.) clarity, and (3.) completeness (Kazdin, 2013). For school psychologists already well versed in applied behavior analysis, these requirements for a workable definition are probably familiar. Confronted with these challenges, Sierra decides she will conduct a partial interval recording of “off-task” behavior using her own observation form (Figure 8.3). She jots down a definition of “off-task” behavior that helps assure Kazdin’s three specifications are satisfied. Thus, at the conclusion of a 10-minute session conducted during a seatwork activity, Sierra has some information pertaining to her student’s rate of off-task behavior.

Lingering Concerns about Behavioral Observations

For all their intuitive appeal, direct school observations of students suffer lingering concerns, and these may constrain their genuine usefulness. School psychologists are urged to contemplate several issues, outlined below.

Reliability Considerations

A first question of any observation system (structured or otherwise) is whether it is reliable. This was made crystal clear many years ago when assessment of ADHD via classroom observation techniques was investigated. There is some good news here. More than 40 years ago Abikoff, Gittelman-Klein and Klein (1977) used structured observations systems of whole and partial interval methodology for 14 ADHD-related dimensions. The researchers investigated, in part, whether observations could actually answer questions about ADHD’s presence. The researchers indeed documented reasonably strong inter-rater reliability (average across 14 behavioral dimensions = .76). In a replication, Abikoff, Gittelman and Klein (1980) produced similar values (average across 14 dimensions = .82). Similarly, a group in the United Kingdom examine the reliability of a structured system (Scope, Empson, McHale & Nabuzoka, 2007). The interval-variant system (counting occurrences within observation intervals) was entitled the Scope Classroom Observation Checklist (SCOC). It required observers to note whether a student expressed several behaviors associated with ADHD: distracted, daydreaming, fidgety, out of seat, interrupting, and off-task. Four two-minute intervals were used. Interval-by-interval agreement between two independent raters was found to be quite high (.989).

In the same vain, there is evidence that the ASEBA’s DOF produces high inter-rater scores regarding “on-task” intervals (r = .92; Reed & Edelbrock, 1986). Conceptual and practically distinct from tallies of intervals, DOF’s summarized ratings seem unique. Recall from the discussion above that this aspect of the DOF is compatible with parent and teacher ratings in that Likert items are checked at the end of the observation. These are then used to generate standard scores on various dimensions. These researchers found quite acceptable agreement among independent raters regarding students “behavior problems” score (r = .83).

All of the news is not good, however. For example, some values cited in the paragraph above are probably inflated. This occurs when total scores (e.g., overall # of intervals off-task) are used to calculate reliability. This method does not mean that two observers agreed on any particular intervals, just that they ended up with roughly similar totals. A large study funded by the Institute of Education Science addressed inter-rater reliability, its level, and how to enhance it. The researchers (Steiner, Sidhu, Rene, Tomasetti, Frenette & Brennan, 2013) argue that an indicator or reliability, kappa, that assesses interval-by-interval agreement is needed. A kappa ≥ .80 was deemed minimally acceptable. Some findings from this study are sobering. For example, using the guidelines in the BOSS manual (Shapiro, 2010b) coupled with video and in-class practice failed to lift observers (e.g., school psychology graduate students) to an acceptable kappa level. Instead, many structured training sessions were needed, the sessions required a skilled instructor who used enhanced and specially honed techniques. Worse, without practice participants lost proficiency over a four-month period. All of this prompted the following comment, “It is estimated that clinicians or researchers….naive to the BOSS, will require approximately 30 training observations to reach proficient reliability” (Steiner et al., 2013, p. 281). Re-read this statement as you contemplate how much confidence to assign to your own classroom observations!

The BASC-3’s manual (Reynold & Kamphaus, 2015) cites an unelaborated study of the BASC-3 SOS’s reliability. The manual-reported study described 19 seasoned SOS users. Video of a single third grade student was used. Without specifying values for the behavior categories individually, the manual reports Part A reliability indices ranged from 44% to 100% and for Part B ranged from 62% to 100%. This is scant evidence of reliability. The manual is silent on the SOS’s validity.

Of course, this leaves a host of other tools and procedures without evidence of reliability. For example, when unstructured anecdotal records are made, what is their inter-rater reliability? Clearly, anecdotal recordings seem ill suited to straightforward reliability calculations. How could agreement be investigated on somethings so open-ended. The fact that there is no clear-cut answer does not remove the risk of poor reliability. What about the reliability of school psychologists’ inferences, not just simple, isolated anecdotal recordings? For example, might Distinee’s appearance (i.e., thin and wearing baggy clothes) be regarded by her school psychologist the same way on two separate occasions? Might two school psychologists make similar inferences if each were to observe Distinee independently? The answer is that we simply do not know. Professional modesty seems in order. Our observations may not be nearly as trustworthy as we are apt to think.

Validity Considerations

There is strong, albeit now dated, evidence that some structured observations are valid, at least for some types of problems. Most-studied appears to be structured observation procedures regarding ADHD (simply referred to globally as “hyperactivity” years ago when these seminal studies were conducted). For example, Abikoff, Gittelman-Klein and Klein (1977) found that 12 of 14 ADHD-related dimensions (e.g., off-task, minor movements, being out of chair) on a structured scale occurred during more intervals in a clinical (ADHD) group than for control participants. ADHD vs. control group differences are necessary but not sufficient to confirm that observation findings can assist in diagnosis. Quite correctly, the authors argued that clinicians also need sensitivity and specificity data. The necessity for “clinical utility” statistics, not just standard research-related evidence of group differences, is precisely Meehl’s persuasive assertion made way back in 1954.

Happily, Abikoff and colleagues shared just this information. For example, observed intervals of off-task behavior were associated with generally high rates of true positives (88.3%) but somewhat lower rates of true negatives (77.3%). Even more impressive was a replication (cross-validation) using new participants (with and without ADHD; Abikoff, Gittelman & Klein, 1980). The second study produced similar results when, as in the prior study, the base rate for ADHD was 50%. Critically for school-based observations, both studies suggested that observational dimensions that might be selected by school psychologists in the field (e.g., off-task behavior) are valid (Scope et al., 2007).

The SCOC, a tool mentioned above, appears to be not only reliable but also valid. It was found to in general correctly classify students with high and low the teacher version of the Conners Rating Scale-Revised (Conners, 2001), with 78% correctly classified. Sensitivity and specificity values are not easily derived from the scores reported in the article, although positive and negative SCOC observation scores appear to predict membership in the non-ADHD and ADHD groups. Again, this study used equal numbers of students with and without ADHD, effectively creating a base rate of 50% for classification purposes. Positive predictive values and negative predictive values would consequently differ in settings with base rates of ADHD either higher or lower than 50%.

School psychologists who consider ADHD as an externalizing phenomenon (i.e., characterized by easily observed student behavior) might anticipate similar favorable validity findings for observing other externalizing problems. But results from an intensive study of 79 preschoolers spanning an entire school year seemed to provide, at best, mixed results. Doctoroff and Arnold (2004) used many assessment techniques, one of which was a partial interval observation recording. The number of intervals during which a summary behavioral observation category called “problem behavior” (e.g., aggression, non-compliance, disruption) was found to predict some end-of-year markers. One example was teacher behavioral ratings (on the Achenbach behavior rating scale) r = .49. This seems to suggest that observations are valid. But the number of problem behavior intervals was not significantly correlated with parent ratings (r = .18) nor with diagnostic interviews of parents (r = .09). Interestingly, the number of intervals during which “prosocial behavior” occurred (e.g., pleasantly conversing, sharing, helping) was not significantly related to the suite of end-of-year outcome variables cited above.

Published validity evidence beyond ADHD and externalizing problems appears to be scant and sometimes disappointing. For example, Winsler and Wallace (2002) executed an intensive study of preschoolers (i.e., approximately 30 10-minute observations on each student across two years). Although reliable, fewer than one-half of the observational dimensions were related to teacher and parent behavioral ratings beyond a chance level. Moreover, observational dimensions that school psychologists might intuitively trust turned out to be only modestly associated with teacher ratings. Specifically, the number of intervals of “inappropriate behavior” observed in class was correlated with teacher ratings of externalizing problems just .31. Intervals of observed “positive affect” and “negative affect” were correlated with teacher ratings of internalizing problems a mere .15 and .21 (and these values failed to reach statistical significance).

One study in particular seems to suggest caution for BASC-3 SOS users. The original BASC SOS (largely unchanged in later versions of the BASC, such as the BASC-3) was checked for reliability and validity (Lett & Kamphaus, 1997). After a 30-minute training session, graduate and undergraduate students observed pupils with ADHD (only), ADHD with a comorbid condition, as well as a group of unaffected peers. Although SOS ratings were found reliable, validity data were weak. Specifically, group comparisons were non-significant regarding four SOS sub-dimensions (i.e., Work on School Subjects, Inattention, Inappropriate Vocalization, and Adaptive Composite). What’s more, just two of five SOS subscales evidenced statistically significant group differences (i.e., Inappropriate Movement, Problem Composite). No consider a stark finding (especially for those who campion observations). In contrast to observation-related findings, results from teacher ratings (i.e., BASC Teacher Rating Scale) resulted in statistically significant group differences. This prompt the following statement, “although observations may be helpful in identifying target behaviors for intervention or classroom environmental factors that need modification, the use of quantitative data from a classroom observation such as the SOS can be deemphasized in ADHD assessment without significantly impacting the diagnosis” (Lett & Kamphaus, 1997, p. 11). In other words, the two researchers, one of whom is a BASC author, imply that teacher ratings alone are just as effective as teacher ratings plus the BASC SOS in identifying ADHD. Interestingly, no new validity studies regarding the SOS are reported in the BASC-3 manual (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2015). In fact, the Lett and Kamphaus study is not even cited in the most recent BASC-3 manual.

Beyond validation of externalizing dimensions, things prove less clear. Worry, compulsions, avoidance, depressed mood, cyclical mood, stereotypic movements, as just a few examples, might all warrant documentation by an observer. Yet systematic, classroom-based validity studies concerning this array of non-externalizing psychopathology seem to be non-existent. This represent a reason for caution when drawing inferences from natural-setting observations.

Cut-score Considerations

School psychologists using behavioral rating scales are already versed in the meaning of cut-scores. Norm-referenced instruments like the BASC-3 and Conners CBRS produce standard scores; their manuals draw a line suggesting scores beyond this point (e.g., T-score = 60; T-score = 70) are probably consequential. Although comparable guidance is afforded school psychologists using standardized, norm-referenced ratings (i.e., ASEBA TOF and DOF) most techniques covered in this chapter leave the observer adrift regarding nomothetically-oriented inference making. It is unclear how many intervals of off-task behavior, for example, might signal a basis for concern. Is it 10%, 20%, 30%? Should the same standards be applied to elementary students and high school students? Should a different threshold apply for students confronted with extremely tedious and monotonous tasks as for those completing relatively high-interest work? As mentioned above, the notion of a comparison peer might assist inference-making about off-task behavior. Although a good idea, observing and tabulating a peer’s behavior hardly ameliorates the issue of concluding whether or not a problem is present based on the degree of problem behavior that you have witnessed. If a target student is off-task during two times as many intervals as a peer is that indicative of a problem? What about 1.75 times as often? What about 1.5 or 1.25 as frequently?

The situation is made no easier for school psychologists when they observe behaviors other than on-task or off-task. How much “Inappropriate Vocalization,” one of the BASC-3’s SOS 14 categories, is sufficient to trigger conclusions that a problem is present? Would it matter if the observed vocalization consisted of “Tattling” vs. “Teasing” vs. “Crying”? After all, each of these three specific actions is enumerated within the SOS’s Inappropriate Vocalization category. Should these three actions really be treated as comparable? Again, the correct answer is not self-evident nor does the test manual tell you precisely what to do. Because errors of judgment are a constant concern among diagnosticians, conscientious practitioners should continue to value what they observe but also remain skeptical. There may be less there than meets the eye.

Cultural and Linguistic Considerations

Bias springing from ethnic group membership is an understandable risk whenever humans observe and characterize one another. You have seen this discussed earlier (Chapter 2, Chapter 5). For example, when an observer and a student are of different cultures or ethnic groups (using the term of Miranda, “ethnic incongruence”), misperceptions are especially likely. A European-American observer, for example, might misjudge an African-American student she is observing in a classroom to be aggressive or lazy. Implicit bias may underlie this risk. But you also learned in Chapter 2 that when school psychologists slow their thinking (use the Reflective System) by leaning on structure and checklists that the chances of biased observations can be reduced. According to the same logic, trusting subjective impressions and summary judgments invites problems (unfettered use of the Automatic System). This, of course, implies that anecdotal observations are particularly prone to bias. There are interesting data that might speak to this prospect regarding one condition, ADHD.

Studying children of various ethnicities (e.g., Caucasian, African-American, Hispanic), Hosterman, Jitendra and DuPaul (2008) found at least one provocative finding. Perhaps as you might suspect, differences emerged across groups. Specifically, scores on teachers’ ratings scales and observation findings from structured classroom observations (i.e., BOSS dimensions such as off-task behavior) were not identical for each ethnic group. But perhaps surprisingly, the degree of rating scale-observation agreement was stronger for ethnic minority students than Caucasian students. This might imply the following, when teachers who are familiar with students’ routine classroom behavior rate a minority student as having an attention problem, school psychologists are apt to perceive the same problem in their classroom observation. But when a teacher rates a Caucasian student with a comparable problem, the school psychologist is less apt to perceive it during her classroom observation. Perhaps heightened caution is needed for students from minority groups even when structured (let alone unstructured) observations are conducted. Thus, school psychologists are (again) urged for most referral questions to carefully weigh all sources of assessment data and tap any structured method that is available to help them do so (i.e., the HR approach).

Summary

Direct observations are commonly used by school psychologists. They enjoy enormous intuitive appeal, in part because we humans are inherently predisposed to observe one another and to reach conclusions based on what we see. In practice, observations range from straightforward techniques that allow inferences about personality and behavioral characteristics to highly structured and norm-referenced procedures. School psychologists are counseled to remember the case-specific purpose of observations whenever they use them and to select their methods accordingly. Time-sampling and recording of overt actions (such as by use of the BASC-3 SOS or the simpler BOSS) are well suited for attention problems and externalizing behavior. In contrast, the ASEBA TOF and DOF represent techniques that sample across an array of internalizing and externalizing problems. Consequently, these norm-referenced options may prove better choices if internalizing hypotheses are dominant. Challenges remain, notwithstanding the popularity of observations. Reliable use of standardized techniques may be more elusive than one might anticipate from their straightforward appearance. Many observations may be required to guarantee adequate reliability. Likewise, validity evident is scant. How to make clinical decisions in the absence of guidance about threshold levels remains a lingering challenge.