9 Student Interviews

Key takeaways for this chapter…

- One broad type of interviewing, diagnostic interviewing, aims to establish a mental health diagnosis, often using a lengthy, structured format

- In contrast, a second broad type, clinical interviewing, can be flexible, brief and tailored to existing hypotheses (working well with the HR approach)

- School psychologists sometimes conduct superficial interviews that are neither diagnostic nor clinical in nature (i.e., surface interviews)

- Some diagnostic interviews have known psychometric properties, including DLRs that allow their entry into a probability nomogram

- Some individual interview items from diagnostic interviews (e.g., feeling unloved, anhedonia) appear to possess outstanding sensitivity and specificity

- Interviews can help to verify (and clarify) critical items (e.g., suicidal thoughts) that a student, teacher or parent earlier endorsed on a rating scale

- Clinical interviews appear to work even in young children, revealing feelings, perceptions, and providing a context of presenting problems

- In practice, building rapport and avoiding excessive direct questioning (grilling) is helpful in eliciting valuable information

Cases/vignettes in this chapter include…

- Ansel, getting past the merely superficial

- Franklin, a clinical interview matching the HR approach

- Dayna, a clinical interview

- Juan, the importance of understanding acculturation challenges

A second-year school psychology graduate student was presenting one of her first cases to classmates and her professor. She was understandably nervous about speaking in this quasi-professional forum. The case consisted of a fifth-grade boy (Ansel) who had incomplete assignments, now had suffered plummeting grades, and moody intervals punctuated with temper outbursts. Like her classmates before her, the graduate student used a PowerPoint format that consisted of pleasing graphics. The student’s presentation was skillfully organized and replete with psychometrics, mostly rating scale scores. Ansel’s background information was made clear through the use of bullet points. It looked like this might turn out to be a case of emotional disturbance and Ansel might be a candidate for special education designation. But as she proceeded, the presentation came to the topic of Ansel’s interview. She stated that much had been learned about this boy during a 15-minute, face-to-face meeting. Here is some of what she shared:

- Ansel was born in Michigan.

- His favorite activity was to play video games.

- He shared a bedroom with his younger brother.

- He preferred to sleep later on weekends than during the week.

- The family owned two dogs and he was sometimes responsible for feeding or walking them.

- Neither he nor his brother received a regular allowance, but his parents were always willing to find chores for which he might be paid.

- His favorite vacation consisted of a family camping trip to the mountains of California.

- He dislikes some foods, especially spinach.

At this moment, a classmate commented, “This is not a session of speed dating. No one cares about his preferences. Don’t you think you should get to the bottom of this kid’s academic skids and his attendance problems? After all, you will soon be a psychologist who should perform like a professional.” This classmate’s comments, despite their ill-mannered tone, convey essential possibilities associated with child interviewing. The graduate student reminded everyone of something that should be obvious. Students are not interviewed merely to collect general narratives about their lives or tidbits about their families. Probably unwittingly, this graduate student engaged Ansel in what might be referred to as a “surface interview.” A surface interview addresses only superficial facts about a student, such as interests and preferences. Critically, a surface interview neglects the prospect of potential mental health problems as well as missing out on students’ perceptions, feelings, and thoughts—considerations that might illuminate their problem and inform intervention efforts. Sometimes practicing school psychologists conduct perfunctory, superficial interviews when a more substantial interview is actually warranted. In other words, social-emotional assessment must concern “information that is meaningful to psychological formulations and diagnoses” (McLeod et al., 2017, p. 232). In this chapter, it is argued that talking directly with a child ought to be uniquely effective in getting to the “bottom of a problem.” But why might interviewing prove especially valuable? Experts have offered several reasons (Mash & Hunsley, 2007).

- Children are uniquely positioned as observers of their own social environments.

- Children’s cognitions and emotions influence their behavior and this fact is relevant in planning interventions.

- Thoughts and feelings (known only to the child) are sometimes the best target of psychological interventions; behavior change alone is not the only legitimate goal of psychological treatment.

- Confirmation of internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety, depression) often hinges on first-hand child reports.

- Well-researched guidelines now exist to show precisely how to interview a child.

Distinguishing Clinical Interviews from Diagnostic Interviews

But before we see how interviewing a child might be done, let’s place the interview process in perspective. For simplicity, and despite inconsistently applied terms, we will describe two broad types of interviews—diagnostic and clinical. Distinguishing the two can help avoid confusion and help you match interview style to situation.

Diagnostic Interviews

Diagnostic interviews, as their name implies, seek a diagnosis. This type of interview is reminiscent of classical psychiatry practice. A psychiatrist, such as a professional working at a hospital or an outpatient clinic, was often charged with establishing a mental health diagnosis for the adults or children sent to him. This was a prelude to treatment planning and case disposition. The psychiatrist’s diagnostic obligation paralleled the obligation of medical colleagues, such as men and women working in internal medicine, orthopedics or cardiology. One of the psychiatrist’s prime diagnostic tools was oral questioning of patients. Interviews often concerned topics such as the presence, intensity, onset, and duration of symptoms associated with the entire array of mental health disorders. Because mental health diagnoses are determined by these factors (i.e., lists of diagnostic criteria found in DSM), it made sense that interviewers worked logically and thoroughly to assure that all potentially-pertinent information concerning all possible diagnoses was collected.

Diagnostic interviews like this tend to be straightforward. The standard introduction to the MINI-KID, one diagnostic interview option for children (Sheehan et al., 2010), for example indicates that most questions can be answered either “yes” or “no”. With direct inquiry and focusing on confirmation (yes) or disconfirmation (no) of various symptoms, diagnostic interviews can take a long time. Probing questions speed the process. For example, disconfirmation of a few anxiety symptoms means there is no need to make other (time consuming) anxiety-related inquiries. Table 9.2 lists some of the standard diagnostic interviews suited for children and teens. Specialized training, almost never part of a school psychologist’s professional preparation, may be required. If you doubt that school psychologists routinely use diagnostic interviews you are correct. Just three percent of school psychologists responding to a survey of assessment practices reported using diagnostic interviews directly with a child or teen (Benson et al., 2019).

In fact, there at least four reasons why school psychologists typically forego diagnostic interviews. First, as you saw in Chapter 3, most referral questions received by school psychologists ask about something other than a specific mental health diagnosis. Questions about special education eligibility are common; questions about DSM-5 diagnoses are relatively rare.

Second, even when a mental health diagnosis is sought, the most efficient means may not be to conduct a child interview. If you recall reading in Chapter 6 about the advent of the MMPI back in the 1940’s, you may already sense the logistical (and financial) limitations inherent in diagnostic interviewing. Compared to the diagnostic interview option for adult patients, the MMPI proved to be an enormous time saver. For example, a 90-minute diagnostic interview may be largely skipped in favor of handing the patient a printed true/false inventory requiring just a few minutes of professional time. Like adult personality inventories in the 20th century, youth self-report scales may afford comparable logistical advantages in the 21st century. Time requirements for an array of diagnostic interview techniques are provided in Table 9.1. Note that the right column indicates time requirements, which can be lengthy.

Third, self-report scales (as an alternative to interviews) are compatible with contemporary psychology’s emphasis on quantification and empiricism. Standardized self-report scales and personality inventories are nomothetic. That is, these tools are long on standardization, normative comparisons and research; they are short on intuition and clinical judgment (considerations sometimes found when clinicians interview patients). In other words, some of the advantages of rating scales over interviews are large and representative national samples (e.g., as found on the BASC-3, Conners CBRS); access to derived scores; repeated instrument refinement when these tools are updated, revised and re-normed; and access to empirical research concerning reliability and validity. Thus, many psychologists prefer rating scales over interviews. Psychiatrists, whose culture and training rarely encompasses psychometrics, continue to emphasize diagnostic interviewing.

Fourth, schools are brimming with information about a child’s social-emotional status. This reality precludes reliance on information from the words of a child herself. The long list of information sources covered in the HR approach makes this clear. If information is needed about the prospect of bipolar disorder, social anxiety, ADHD, or autism spectrum disorder, then teacher interview, observation, cumulative folders and behavioral rating scales’ scores often do much of the job.

Table 9.1 Various Diagnostic Interview Choices for Use with Children

|

||||

|

Name of Technique |

Style | Focus | Time requirement | Specialized training needed? |

| K-SADS or Kiddie SADSa | Structured | DSM | 1 hour + | Yes |

| DICAb | Structured | DSM | 1 to 1.5 hours | Yes |

| CASc | Semi-structured | Content areas + DSM | 1 hour or less | No |

| MINI-KIDd | Structured | Specific diagnoses and/or groupings | As little as 15 minutes | No |

| K-SADSa = Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, School-age Children, DICAb = Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (MHS), CASc = Child Assessment Schedule (Hodges, Kline), MINI-KIDSd = Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents | ||||

The reasons for deemphasizing diagnostic interviews in schools notwithstanding, diagnostic interviews are neither valueless nor devoid of research support. Indeed, there are times when a school psychologist might choose to skip self-report measures while still seeking diagnostic information directly from a child herself. Maybe the child is too young or does not read well enough to complete a self-report scale. Perhaps she seems too unmotivated, or too openly hostile, to complete a self-report scale. In instances like these, especially if an internalizing problem is hypothesized, a diagnostic interview may be needed. Research confirms that diagnostic interviews often possess useful information (see Table 9.2). Some of the effect sizes are comparable or better to rating scales. Results from them might also be used in probability nomograms.

Table 9.2 Effect Sizes and DLR Values Associated with Selected MINI-KID Dimensions |

||||

| Dimension (MINI-KID diagnostic family) | Effect size associated with positive score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Positive | Effect size associated with negative score | Diagnostic Likelihood Ratio Negative |

| Mood disorder of any type | Small |

3.5 |

Moderate |

.20 |

| Anxiety disorder of any type | Small |

3.9 |

Moderate |

.13 |

| Substance abuse of any type | Moderate |

5.9 |

Large |

.02 |

| ADHD of any type | Small |

4.2 |

Moderate |

.15 |

| Behavior disorder of any type | Small |

3.5 |

Moderate |

.13 |

| Psychotic disorder of any type | Moderate |

8.3 |

Large |

Approximately 0 |

| Eating Disorder of any type | Large |

71.0 |

Small |

.29 |

| Source: Sheehan et al. (2010) | ||||

Clinical Interviews

It can be helpful to contrast highly structured diagnostic interviews with their less rigid and less symptom centered counterparts–clinical interviews. Clinical interviews might be used when diagnoses are not the chief concern (i.e., an exact diagnosis was never embedded in the referral question). For example, some cases turn out to be all about behavior, feelings, and social interactions (e.g., student-to-student conflict, demoralization about academic progress) but not about making an exact DSM-5 diagnosis. The logic behind clinical interviews and the methodology for their execution is detailed in popular sources, such as Greenspan and Greenspan (2003) and McConaughy (2013). Consulting sources like these can help you hone your array of clinical interviewing skills. The idiographic possibilities inherent in clinical interviews are evident in the words of those who champion speaking directly with students: “Clinical interviews offer good opportunities to assess children’s perspectives on their friendships and relations” (McConaughy 2013, p. 53). This means that clinical interviews can address more than whether a child is an outlier on a psychological dimension (e.g., social skills) or expresses a diagnosable condition (e.g., depression). In other words, clinical interviews permit school psychologists to focus on the uniqueness of each child’s perceptions, beliefs, worries, conflicts, affiliations, supports, and aspirations without necessarily ignoring nomothetic categories.

But how do school psychologists actually avoid the triviality of surface interviews? In concrete terms, what should be included in a meaningful clinical interview? Perhaps most important, where do school psychologists find templates to guide them through such interviews? You’ve already heard about the benefits of structure and checklists. Recall that by providing scaffolding, such tools help assure that important elements are not overlooked and that practitioners engage in deliberate, careful thinking (the Reflective System). The same is true regarding clinical interviews while still avoiding the straight jacket sometimes inadvertently imposed by textbook diagnostic interviews. You will see two options, a clinical generic one (Figure 9.1) that hits most of the critical topics as well as, later in the chapter, a hybrid option that blends elements of clinical interviewing with objective ratings of psychopathology (the Semistructured Clinical Interview of Children and Adolescents, SCICA, McConaughy & Achenbach, 2001).

There is, of course, an artful element to interviewing children and teens. It’s not all about just knowing which questions to ask and then mechanically posing them. Plus, there are obligatory topics to address even when conducting a relatively unstructured clinical interview. Thus, a digression is in order before you learn more about the content of clinical interviews.

Interviewing Skills and Obligations

The goal of clinical interviewing is to: (a.) get each child to begin to talk with you, and (b.) to get each child to share relevant information as they talk. Some students can move directly to b. Many, however, must first transit through a. A few even resist the most benign aspects of a. Unfortunately, it is often impossible to ascertain which type of child is present before you start. Thus, you might assume the worst and use many of the techniques mentioned below right from the outset of your interview session. The list of interview techniques listed below is certainly not exhaustive. You also have ethical obligations regarding confidentiality as well as a need to do due diligence by ruling out some potential considerations. The material below can help you with these considerations.

Explain Confidentiality and Secure Assent

Older students, as well as younger ones who worry that disclosure may get them into trouble, sometimes clam up. They need assurances, the most important of which is that potentially embarrassing information won’t be shared. Even better would be absolute confidentiality, but this is not possible even for licensed psychologists working in clinics (i.e., threats to self and others cannot be kept confidential). Moreover, the American Psychological Association Code of Ethics calls for confidentiality but recognizes that state laws and institutional rules may compel practitioners to sometimes disclose confidential information (American Psychological Association, 2017). In schools, it is similarly impossible to promise that information won’t be shared with team members or parents. The NASP Principles of Professional Ethics call for privacy and indicate that students’ disclosures to school psychologist are often confidential but that state laws may specify otherwise (NASP, 2010). Students deserve to know these realities before they share sensitive information. They also need to agree to them (referred to as “assent”), which is mandated by professional ethics (e.g., NASP, 2010). What’s more, school-based practice means that there are plural stakeholders (e.g., school administrators, teachers, parents) who need to understand the rules of confidentiality. Thus, local practices as well as ethical and legal responsibilities need to be considered when confidentiality is explained. Beginning school psychologist should discuss these topics fully with a senior colleague or with their immediate superior.

Assure an Adequate Physical Set Up

Some things are obvious but nonetheless occasionally forgotten. It’s tough to carry on any conversation without an isolated space free of excessive noise. Find a set up where you do not have to shout to hear one another and where the child is certain he will not be overheard. Some children, especially boys, do not like a face-to-face set up. They talk more openly when sitting beside (rather than across from) the diagnostician. Too much eye contact may induce anxiety and promote reluctance.

It’s Okay to Ask the Child to Draw

Research suggests that drawing during an interview may promote information sharing. A New Zealand study, for instance, found that children (5-12 years) who were asked to “draw and tell” during a clinical interview provided twice as much verbal material as counterparts in a “tell only” condition (Woolford, Patterson, Macleod, Hobbs & Hayne, 2015). Presumably, many children are more comfortable when drawing.

Consider Small Talk to Establish Rapport

Small talk is a good starting place because it can serve as an icebreaker (Murphy, 2014). This is exemplified by a school psychologist who starts with–“Is it ever going to stop raining?” or “I love Tuesdays because it is always ‘taco Tuesday’ in the cafeteria.” Obviously, the intent is not to convey facts or solicit information. The school psychologist, rather, is communicating a critical implicit message: “I’m not here to grill you; I’m actually human, just like you.”

Start with Non-threatening Topics

“So, let’s see, we have a morning and a noon recess on this campus, right?” Like the small talk mentioned above, this question is unconcerned with actual facts (the school psychologist already knows the school schedule). Questions like this aim to start the child talking. The same is true of, “Are there more boys or more girls in your classroom?” (an easy question for children to answer). The same is true for, “I think the principal makes everyone have a hall pass to visit the restroom.” Children quickly say whether this is true or false. Once they answer just a few factual questions, children find it easier to continue to talk when less comfortable topics (e.g., inquiries concerning misbehavior or mood) come up. The general progression is envisioned as unthreatening topics being covered first, followed by somewhat uncomfortable topics, with the most uncomfortable inquiries saved for the last stages of interview.

Don’t Neglect Open-ended Questions

An urge to cover specific topics can sometimes promote an overly questioning style. Consequently, an interview risks devolving into an interrogation. Sometimes, however, it works well to merely pose an open-ended question and then harvest the results. For example, one study found clinical interviews were able to elicit valuable psychological information even among young children (e.g., as young as 5 years). Interestingly, this study’s interview procedure started with an open-ended question about each student’s understanding of a presenting problem (Macleod, Woolford, Hobbs, Hayne & Patterson, 2017). This interview approach can be understood by considering how it treated the presenting problem of “worry.” Specifically, research participants were instructed to tell everything possible about their “worry.” Use of open-ended questioning was found to generate extensive psychological information, and most of it was judged to be relevant (using a complex research coding strategy to determine relevance). In fact, a general inquiry about worry opened the door for research participants to talk about numerous topics: affect, cognitions, timing of the problem and its expression, physical aspects of the problem, overt behavior, environmental context and individuals in the environment related to worry. You will recognize information like this as idiographic (concerning the uniqueness of the child herself). In other words, non-directive exchanges between interviewer and child tended to elicit just the type of information that can help school psychologists use the HR approach when more than a circumscribed diagnosis is sought. As part of a controlled research study, interviews were relatively fixed. But practicing school psychologists do not suffer these research-associated constraints. Instead, school psychologists can use clinical interviews flexibly to follow existing leads or to come up with new ones.

Treat Interrogatives as a Limited Resource

As suggested above, open-ended questions like “tell everything you can about feeling angry” are often best. Sometimes, however, even the most skilled clinical interviewer needs to pose questions. These may take the form of interrogatories: who, what, when, where, why, how, etc. When these words are used, the interview can quickly turn into an interrogation. Facts and opinions may be forthcoming, but a child may soon feel that she is being grilled. Relatively brief answers may give way to very short answers, followed by “I don’t know” or shoulder shrugs. For these reasons, it is often best to guard the supply and to use cautiously a potentially-limited supply of interrogatives.

Use Minimalistic Encouragers

These terms were used by Woolford and colleagues (2015) in their study of interviewing. They propose that simple statements like “wow,” “good,” “that was tricky” serve to encourage ongoing talking and consequently information sharing. Simple, non-probing statements like this probably help the child to relax and talk more freely. Reflection of what the child has said via paraphrasing may also help. These practices are used in non-directive psychotherapy where they are known to support a client and to keep him talking (see Dayna’s interview in Illustration 9.2).

Avoid Power Struggles

What is a power struggle? It occurs when one person (e.g., an adult) tries to make another person (e.g., a child) do something over which he/she lacks power. In a power struggle, the child refuses, and the adult is powerless to induce compliance. For example, a parent tries to make his son “be appreciative.” Obviously, there is no way for the parent to make this happen. Unfortunately, the more the adult tries, the greater the power gained by the child. School psychologists are advised to avoid power struggles, including during clinical interviews.

The antidote to a power struggle is disengagement. Parents hoping for an appreciative offspring are often better off to avoid talking about appreciativeness and finding a more tangible goal. Alternatively, they might subtly encourage appreciativeness whenever it is seen. This line of discussion is consequential because occasionally a child attempts to engage a school psychologist in an interview-related power struggle. Says the noncompliant student: “Okay, I’ll go to your office, but I will not talk.” An insightful school psychologist might respond: “It’s up to you. I’ll just do some paperwork while you wait and maybe later you will feel like talking. Or, maybe not. I can’t decide for you.” A less insightful school psychologist might respond: “Well, you are going to have to talk so you had better decide to right now. I don’t have all day to wait around for you.” In one scenario, the school psychologist has inadvertently handed the child enormous power, whereas in the other she has arguably avoided falling victim to the child’s attempt to control the situation. Unfortunately, sometimes situations just like this occur. Generally, the best course for school psychologists trapped in situations like this is judicious action couple with hope that the child eventually accedes to an interview.

Promote Talking without Asking Questions

Reticent and resistant children often talk more if they listen first. Thus, rather than launching into a series of questions aimed at the child, some school psychologists recount their day, their own school experiences, their favorite school subjects when they were young, their own favorite on the cafeteria menu, their evaluation of the school layout, etc. Shy children in particular may relax in such a scenario (attention is directed away from them and they are required to do nothing). Resistant children have nothing to resist (power struggles are avoided). Moreover, by moving her narrative to various topics (those she recounts about herself), the school psychologist can sometimes cover important issues with little direct questioning. “I remember when I was in the fourth grade. We always had recess outside. There were a lot of kids, some nice, some not so nice. Some friendly, some not so friendly.” Statements like this coming from the mouth of a school psychologist can sometimes induce a surprising amount of disclosure about students’ own recess experiences, their perceptions of classmates, or their successful (or unsuccessful) efforts to gain friends.

Pave the Way in Advance for Embarrassing Responses

Some topics need to be addressed directly via unambiguous questions (e.g., history of trauma, suicidal thoughts). Children may avoid honest disclosure for fear of embarrassment or being “different.” Thus, sometimes school psychologists need to enable honesty by acknowledging that an entire spectrum of responses is common. “I need to ask you a personal question that might be a little embarrassing. But first I need to tell you that I hear all kinds of answers. When I ask this particular question, some kids say, ‘no way, not true for me.’ Other kids say, ‘yes, that’s true.’ Some kids even say some pretty strange stuff. So, anything you say is okay.”

Manage Challenging Students Professionally

Occasionally students challenge the skills and competence of the school psychologist (“I don’t think you know what you are doing.”). Others may become openly confrontational (I’m going to leave your office. I’d like to see you stop me.”). Sattler (2014) lists a number of these rare occurrences and potential ways to manage them. His classic text proves an excellent resource to consider when any of these unusual situations arise in your own practice.

Inquire about Depression/Suicidality

Depression is common and for any face-to-face encounter between a student and a mental health professional (including a school psychologist) it should not be missed. The same is true concerning the prospect of suicidality. Consider the following sobering statistics regarding the latter concern: the Centers for Disease Control reported that 17.7% of high school students indicated that they had seriously considered suicide during the past year and 14.6% said that they had made plans to complete a suicide (Kann et al., 2016). These same considerations are rarer, but not unknown, among younger students. Psychotic disorders, mood disorders, and behavior disorders coupled with anxiety or mood problems further boost the risk of suicidal actions (Sheehan et al, 2010). You will see important details about this critical topic later in this chapter (i.e., in a section entitled “Suicide Risk Interviews.”)

Inquire Routinely about Trauma

Trauma is common and should be routinely ruled out in social-emotional cases. For example, many children have been exposed to a high-magnitude stressor events (e.g., natural disasters, serious accidents, major illness, death of a loved one; Fletcher, 2007). A 2008 survey supported by the CDC and reported by the U.S. Department of Justice revealed stark findings: 46.3% of surveyed youth had been exposed to an assault during the past year; 24.6% were victim of a robbery, vandalism or theft; 25.3% witnessed a violent act (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, Hamby & Kracke, 2009). Events like these can contribute to, or even cause, presenting problems mimicking anything from hyperactivity to anxiety to depression.

Thus, a general question about trauma might be asked routinely, with more focused questions employed in the presence of community-wide or region-wide trauma producing events (e.g., in Puerto Rico after the occurrence of hurricane Maria). A general inquiry might be something like this: “Some kids tell me that they have had very scary or very awful things happen to them. I’m just curious if anything like that has ever happened to you.” A more focused inquiry might be along these lines: “I know that the hurricane caused a lot of damage. Kids are telling me a lot of things. Can you tell me what the hurricane did to you and your family?” Detection of a concern can prompt the school psychologist to conduct more detailed questioning or even to lodge an outside referral to someone in the community more accustomed to assisting youth with trauma. Critically, general questions about trauma occasionally result in specific responses that imply physical abuse, sexual abuse, or neglect. As discussed earlier (see Chapter 3), these are indications for an outside referral according to mandated reporting procedures (e.g., direct contact with state-level Child Protective Services). School psychologists do not themselves conduct interviews regarding physical or sexual abuse or neglect. Chances are that your district already has a policy concerning potential abuse and neglect. Consider checking with your supervisor if you are unsure.

A history of trauma can, of course, trigger a need for an intervention. Unrecognized or poorly understood, it can also lead to a mischaracterized problem. For example, a child who presents with moodiness might be conceptualized as a commonplace example of an affective disorder. But case formulation would necessarily change if it is learned that there was a devastating home fire from which a sibling suffered severe burns and from which the student himself barely escaped death. The treatment needs in the former situation may prove different from those in the latter. For a student like this, many school psychologists would envision out-of-school treatment. Full blown PTSD or related problems like maladaptive grief (MG) may be too much for school psychologists. Indeed, there are specialized skills, such as cognitive behavior therapy (Cohen, Mannarino & Debilinger, 2012; Joyce-Beaulieu & Sulkowski, 2015) that may be lacking or not feasible for implementation by school psychologists. On the other hand, it is argued that systemic attention and supports for students with a history of trauma, sometimes referred to as “trauma-informed” is essential in schools (Chafouleas, Johnson, Overstreet, & Santos, 2016). Regardless of whether or not systemic supports are developed in your school district, school psychologists are encouraged to make routine inquiry about a history of trauma among referred students and be prepared to advocate for needed interventions. And, as you saw in the case of Judy in Chapter 7, the flexibility of interviewing may be preferred to the use of narrowband checklists when a history of trauma is known.

Inquire Routinely about Substance Abuse

Alcohol and substance abuse are also common. For example, the Centers for Disease Control found in 2016 that approximately 8% of boys and girls (age 12 and older) had used an illicit drug at least once during the preceding month. Binge drinking was reported among approximately 5% of youth, with a slightly higher rate for girls than boys https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2017/050.pdf. It can be argued that these possibilities should be routinely ruled out in adolescent social-emotional cases. Consider the following statement, “when substance use disorders occur in adolescence, they affect key developmental and social transitions, and they can interfere with normal brain maturation. These potentially lifelong consequences make addressing adolescent drug use an urgent matter” (National Institute of Drug Abuse, 2014, p. 5).

Treatment is possible but only with problem detection. For example, research confirms that parents can operate as “interventionists” that lead to positive outcomes regarding drug abuse (Winters, Botzet, Dittel, Fahnhorst & Nicolson, 2015). Similarly, professional treatments with demonstrated efficacy have been documented, ranging in intensity from online options (Trudeau, Black, Kamon & Sussman, 2017) to facility-based treatment with embedded mental health services (Ramchand, Griffin, Hunter, Booth & McCaffery, 2015). Need for parental involvement necessarily makes this line of questioning essential. Critically, however, local school policies should be carefully considered before entering this line of questioning. Minimally, your promise of confidentiality to a student vis-à-vis parents and administrators must be absolutely clear before broaching this subject with any student.

Clinical Interviews-Two Cases

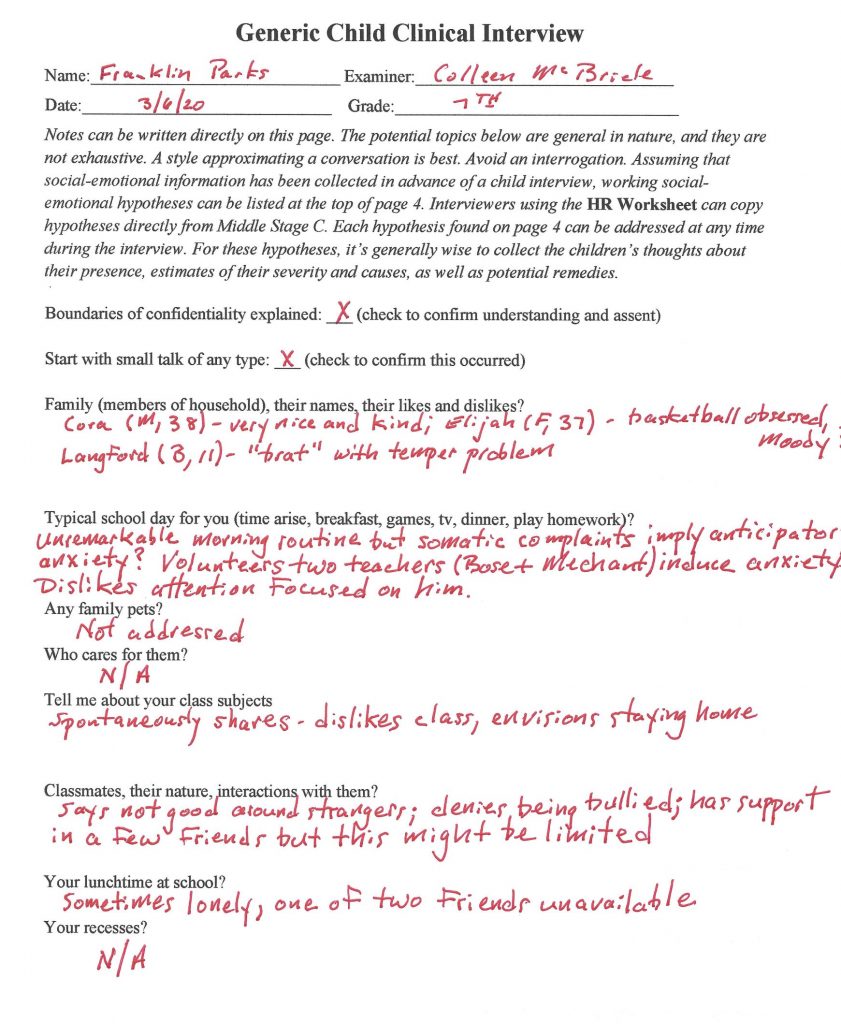

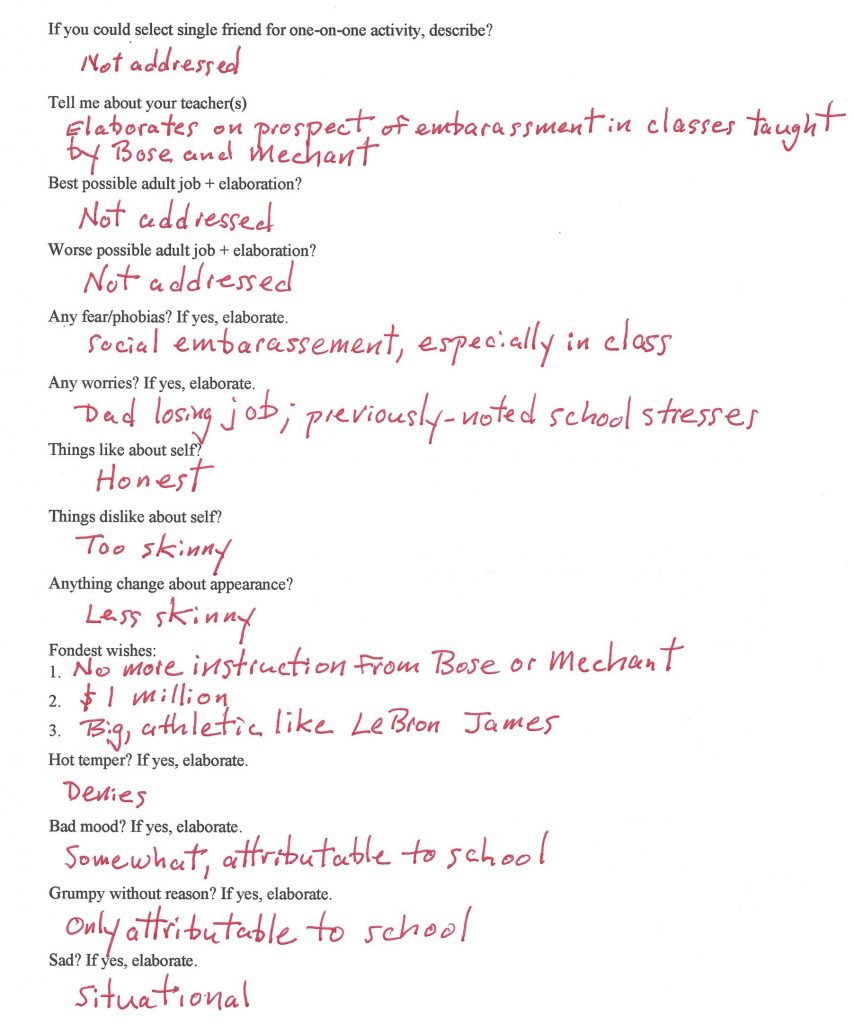

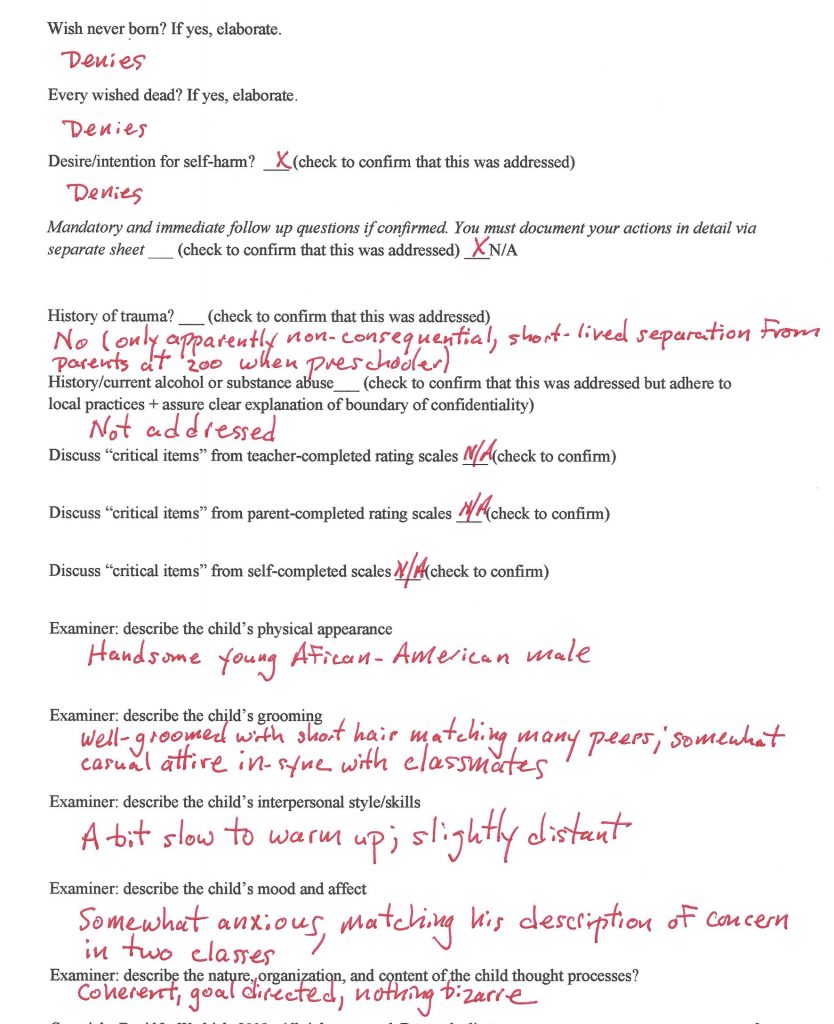

How might a clinical interview be conducted? Figure 9.1 illustrates a Generic Child Clinical Interview form. Blank versions of the Generic Child Interview Form are provided in the Appendix; they can be copied and used in your practice. The form can assist you in a variety of interview situations. Two cases with help make this concrete.

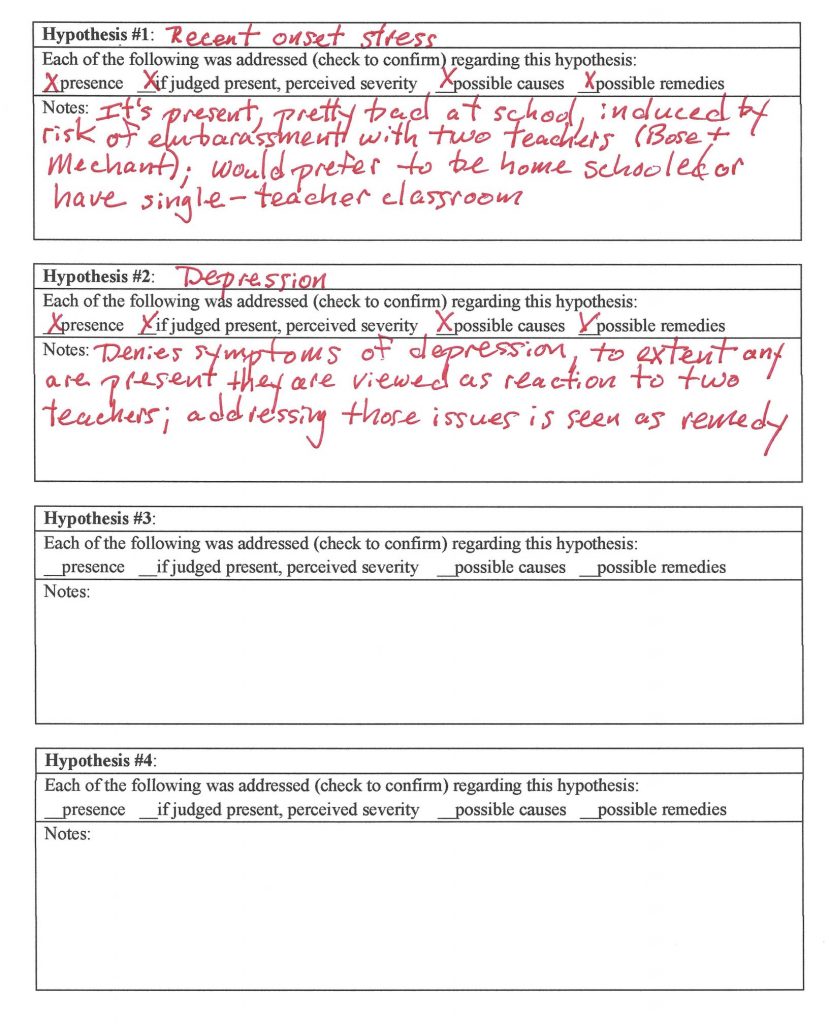

Interview of Franklin Parks

Franklin Parks is a student you already met in Chapter 2. But until now you never heard the details of his clinical interview. To make things concrete, you will soon see a verbatim interview with Franklin (Illustration 9.1) that resulted in the notes that appear about him in Figure 9.1 – Figure 9.4. Please observe that the school psychologist used the Generic Child Interview Form to summarize the interview. She did not write Franklin’s responses verbatim and she did not follow items in the exact lockstep order listed in the form. School psychologists-in-training may be required by their instructors or supervisors to record responses word for word (or even to audio-record them, but this practice is rare among experienced practitioners). Although the Generic Child Interview Form is just one option (many school psychologists create their own), it is arguably suited to most social-emotional assessments in schools. As such, it encompasses many of the points mentioned above, plus a few others that match the HR approach (seen in Chapter 2). Specifically, the Generic Child Clinical Interview includes several “to do’s” that might be considered essential for each clinical interview:

- explaining confidentiality

- establishing rapport (via small talk)

- assuring depression and suicidality are addressed

- ruling out a history of trauma

- ruling out substance/alcohol abuse problems

- following up on critical items endorsed by teachers, parents or the student himself on rating scales

- focused inquiries about existing hypotheses

As school psychologists address each of several critical tasks (e.g., rapport building, ruling out a history of trauma), they verify having done so by checking boxes found on the interview form (again, checklists help tame troublesome heuristics and assure thoroughness). The Generic Child Clinical Interview also integrates student interviews with this book’s HR approach. Specifically, the final page of the form facilitates direct student inquiry about each working hypothesis present during the Middle Stage of analysis on the HR Worksheet. It’s not necessary to use the HR Worksheet, but it does integrate easily with the type of interview prompted by the Generic Clinical Interview form.

The logic is this: it’s important to routinely tackle several standard interview topics, some of which are relevant to most children. However, it’s also essential to deal with specific concerns that might explain each student’s particular presenting problem. Thus, the final page of the interview form prompts the school psychologist to list each continuing hypothesis. Doing so would typically include asking the student her thoughts about the presence/credibility of the hypothesis, an estimated severity of any problem, speculation about the source/cause of the problem, and any notions about how to overcome it (this might help to get to “the bottom of the problem”). Boxes pertaining to each of these: (i.e., presence, perceived severity, possible causes, possible remedies) are found under each hypothesis. To assure each is addressed, school psychologists again confirm (checkoff) completion as they work. The bulk of the 4-page Generic Child Clinical Interview form, however, merely lists topics that are to be covered for most students. Topics are covered in whatever depth the interviewer deems appropriate, although elaboration is routinely sought as follow up on initial questioning. For example, if a student indicates a phobia is present, details about setting, severity, duration, etc. associated with that phobia might be sought. Some topics can be skipped, and other can be added at the interviewer’s discretion.

Now let’s revisit more closely the case you saw in Chapter 2, Franklin Parks. Figure 2.1 is the HR Worksheet for Franklin. As an examination of Figure 2.1 reveals, the school psychologist had already executed several stages in the assessment process (i.e., Initial Stage, Middle Stage A, Middle Stage B). In using the HR Worksheet, she has arrived at Middle Stage D (she deemed broadband rating scales to be unessential and thus skipped Middle Stage C). She is prepared to interview Franklin as the next pro forma assessment stage. As indicated in Figure 2.1, as the interview approaches, the list of working hypotheses has been winnowed down to just two:

- depression

- recent onset stress

Now read the interview found in Illustration 9.1.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Good morning, Franklin.

FRANKLIN: Hi.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Thanks for coming down to my office. I hope I didn’t pull you away from anything important in class.

FRANKLIN: No, nothing at all.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Are we in second period right now?

FRANKLIN: Yes.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: That’s what I thought. I can never quite keep the times exactly straight and we don’t hear the bells in the section of the building at all.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Did you have a nice weekend?

FRANKLIN: Yes, but I would like an even longer one.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: You and everybody else. Well, I wanted to talk with you for a while today to get to know you better generally. But also, we–I mean your parents, teachers and I–hope to get to the bottom of what’s going on with your absences and slipping grades. I explained this to you earlier when we chatted briefly.

FRANKLIN: I remember.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I need to explain the rules. What you say to me in here is generally confidential. I won’t share particular details with your mom or dad or anybody else. But I have to tell you that these rules don’t apply in two situations. The first is if I learn that you intend to hurt yourself. The second is if I learn that you intend to hurt somebody else. In either of those situations, I can’t keep what you said confidential. Fair enough?

FRANKLIN: Yah. Seems fair to me.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Did you know that I talked with your mother already?

FRANKLIN: She told me that you did but she really didn’t say much about it. I wasn’t surprised.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Can you remind me of your mother’s name?

FRANKLIN: She’s Cora.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Good, and can you tell me the names of everybody else who lives in your home?

FRANKLIN: There’s my dad, Elijah, my brother, Langford, and then there’s me.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Do you know everyone’s ages?

FRANKLIN: Langford is 11 and I think my dad is 37 and my mom is 38.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’m curious what they’re—I mean the people you live with are actually like.

FRANKLIN: Langford can be a brat. He’s not at all good at sharing. When we were little, we had to share a room and I hated that. My dad…hmm. I guess I would have to say obsessed with sports. He watches NBA games all the time. My mom is very nice and kind.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’m interested in what schooldays are like for you starting from when you wake up in the morning.

FRANKLIN: I wake up about 6:45 and have breakfast right away before I shower. My dad is already at work. My mom is about ready to leave. She gets us out the door at 7:20 to catch our bus. Well, actually Langford’s bus is a little later. I’m not sure…I don’t know the exact time for his.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Are you a morning person?

FRANKLIN: On weekends yes, but during the week no. Sometimes my stomach feels funny. And sometimes I don’t want to even go to school.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Sounds like nerves.

FRANKLIN: There’s certain things about school I don’t like. And I think that has something to do with feeling like I want to stay home.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Ah, can you explain?

FRANKLIN: Well this year just seems harder and more complicated. I have six classes every single day.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: But don’t we all have favorite subjects? Then all the other subjects we don’t like as much. Maybe you’re telling me this is different for you. You dislike them all? You would like to avoid school altogether?

FRANKLIN: That’s not really it. I have two teachers after lunch that I really do not at all like working with. I start worrying and feeling uncomfortable thinking about those classes taught by those teachers during lunch.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Can you tell me some details?

FRANKLIN: Well, it’s fourth hour, which is Mr. Bose, and fifth hour, which is Mr. Mechant. Both can sometimes be mean. They like to embarrass students. Plus, I know that I’m pretty easily embarrassed.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Easily embarrassed?

FRANKLIN: Well, yep, I don’t like having attention called to me. I hate being put on the hot seat.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I think I understand. It seems to you that these two teachers like to put you on the hot seat and they sometimes embarrass you.

FRANKLIN: Well, not exactly. They haven’t actually done anything directly to me. Not so far. I’ve seen plenty of other students get plenty embarrassed in front of class. I’d rather not do a lot of talking up in class. I’d just like to do my work and be left alone. But both of these guys make kids recite out loud in class. Some questions are really hard. Maybe I’m just a little bit overly sensitive.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I see, judging what you’ve seen in class, you think that someday you’re going to get embarrassed. But not yet. What about the students in these two classes? What are they like? Are they doing anything to add to the possible embarrassment?

FRANKLIN: Nothing special. They’re not teasing or bullying or anything really like that. They’re okay. My mom’s always told me that I’m shy and so maybe it’s just my shyness not really anything about the students. I can kind of see them in the back of my mind. You know, imagining a couple of them laughing at me if I said something stupid and the teacher, especially Mr. Bose, kind of like smiling and smirking.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Smiling and smirking? I think I know what you mean.

FRANKLIN: Ah, actually, both of them. It seems like they get pleasure from seeing student’s fail. They seem to react like they know everything and all students are a pretty dumb bunch of dopes.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: This must be upsetting to all the students.

FRANKLIN: Not sure, never really talked it over with anybody.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I see. You haven’t really talked it over. Well, do you have friends who you can talk with?

FRANKLIN: I have some friends, but I’m not good around strangers. A new school means a lot of strangers. Only some kids were from my old elementary school. A lot weren’t. That’s why liked it better before coming to this bigger middle school. Last year we had had one or two teachers, like a second one in math, instead of six different teachers like I have now.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So back to your classmates, I just want to make sure that there is no teasing or bullying going on that has anything to do with this situation with you.

FRANKLIN: I’ve seen it [bullying, teasing]. I don’t think I’ve experienced any myself directly.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So, who do you hang with?

FRANKLIN: Sure, I have two good buddies. Too bad that one of them has the first lunch hour. My other friend is not 100% available or sometimes not even at school. Sometimes I eat alone.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: These friends, the ones you mentioned, do you share things with them? Do you think of them as supportive and helpful?

FRANKLIN: Well, my number one friend, I told him about these teachers. He gets it. I’m glad I have them as friends, but it really doesn’t solve the problem.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So, do you think this is all going to get better? How bad is it?

FRANKLIN: I’d say it’s pretty darn bad. I have a fantasy. My mom would quit working and go ahead and just homeschool me. That would solve the problem. Otherwise, I’m not sure how the situation would get any better.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: You wish your mom would do this? Maybe she will.

FRANKLIN: Never, no way, no how. She wants me at school. She’s very nice and understanding. But she big time insists I go to school.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Okay, I guess that option gets crossed off your list.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Earlier, if I understood you, you described yourself as shy. Sometimes shy kids are also worriers.

FRANKLIN: I’d say I’m about an average level worrier. When my dad complains about problems at his work I do sometimes worry a little that he might lose his job. But usually I don’t think about that. My friend, the one I told you about, worries about everything. I’m not a worrier at all like that.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’m curious if you see yourself as easy-going or as having a temper, somebody easily upset.

FRANKLIN: I don’t think I’m exactly easy-going. But I do have a temper once in a while. Temper? Ah, that’s Langford. That’s a kid with a bad, bad temper. Plus, he never ever apologizes.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I think I know what you are talking about.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: How about your mood? Can you describe what it is like?

FRANKLIN: I get down in the dumps from time to time. But I’m not really sad, if that’s what you’re asking about.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well, yes, I’m kind of asking about that but some kids tell me that they’re not necessarily sad but they could be grumpy. Grouchy.

FRANKLIN: Maybe a little bit. My mom says that my dad could be really grouchy.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So, are you talking about arguing and disagreements between them?

FRANKLIN: No, they get along pretty good. I’m talking about my dad being grouchy.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’m not sure I understand.

FRANKLIN: Oh, it’s all about basketball. When his team loses, there’s bad stuff coming for the rest of the day.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Oh, I see. But back to you. I have to ask you, are there times when you felt so sad that you wished you would never been born?

FRANKLIN: Maybe, like maybe when it’s been a really bad day with Mr. Bose or Mr. Mechant. Ah, ah, but no, not really.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: How about ever wishing that you were dead? Or even thought about killing yourself?

FRANKLIN: No, but I wished I was at a different school sometimes. A different school would give me no Mr. Bose and no Mr. Mechant. I have even thought what it would be like if I just had one teacher in seventh grade instead of six teachers and that one teacher was really nice.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Seems like after we collect all of the information then we will need to make plans to have things get better for you. But now, so I’ll understand better, let’s think about some positives. What do you like about yourself?

FRANKLIN: My mom says I’m honest and I’m responsible. I guess she’s probably right.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Everybody has something they don’t really like about themselves, what about for you?

FRANKLIN: I’m too skinny. My dad says I’m too skinny. My friends say I’m too skinny. I am too skinny.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Are you a picky eater or is this just the way your body naturally grows?

FRANKLIN: I’m a little bit of a picky eater but I eat a lot. I won’t eat broccoli and I will not ever eat cauliflower. I think I just can’t gain weight. My dad said that he was super skinny when he was young too.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I also have to ask you this one. Anything awful or terrible or frightening happen to you in your life?

FRANKLIN: When I was little, and we were all at the zoo, I wondered off from my parents. I couldn’t find them maybe for about 5 minutes or so. My parents were very scared, and I guess it was kind of scary. I still remember it a little bit even though my mom said I was just three. Well, maybe I just think I do ‘cause mom and dad have told me about it a bunch of times.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Wow, that does sound scary. But, anything more awful than that?

FRANKLIN: No, not really.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Just a few more things. I want you to suppose that there were magical powers that could make things happen. As part of this, you could be granted three magical wishes. All you had to do would be to make your wishes, and three of them would come true. Could you tell me what your wishes would be? Remember, only three.

FRANKLIN: First, different teachers for my fourth hour class and my fifth hour class. Second, I guess I would go with a million dollars in cash. Third, hmmm. This is a little bit harder. How about I would suddenly be very big and very athletic. I’d be like Lebron James. Those would be three good ones!

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So, at this point I think you’re saying you have a lot of stress related to fourth and fifth hour classes. And you are also saying that you believe that some of the stress comes from the way these two classes are taught. Right?

FRANKLIN: Exactly.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Big time problem or not?

FRANKLIN: Pretty big time.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: And you’re thinking that having different teachers during those hours may solve some or all of the problem?

FRANKLIN: Yes, I think it would.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I just want to go into a little detail to make sure that I understand well. Here’s a few things I want to ask about. I want to be sure I understand, is it true that you have a good appetite even though you describe yourself as skinny?

FRANKLIN: Yep. I eat a lot. I’m hungry a lot.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Okay. Can you describe sleep for you as an individual? You said you get up pretty early for school. Do you sleep soundly or wake up a lot?

FRANKLIN: No, once I go to sleep, I sleep. Mom says I’m dead to the world.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: But how long to fall asleep?

FRANKLIN: Maybe 10 minutes.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: How about on weekends.

FRANKLIN: I stay up to maybe 10:00 and sleep until 9:30.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Nap?

FRANKLIN: Nope. Not for me.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Is this enough to give you energy or are you tired during the day?

FRANKLIN: I don’t really feel tired very often, except in P.E. when we have to run 800 meters, twice around the track.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I didn’t get the sense that there is all that much that you are unhappy about concerning yourself.

FRANKLIN: No, I’d just like school to be different.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: When I talked with your teachers, they didn’t mention that you had trouble paying attention or organizing yourself at school.

FRANKLIN: You mean ADD?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well, not exactly. But what do you think?

FRANKLIN: I’m pretty focused but I’m a little nervous, or more than a little, in the two classes I told you about.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Will this end up getting better? What does the future hold for you?

FRANKLIN: I think it will. I liked school okay with other teachers last year and most of my classes are okay. It’s just those two.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Okay, I think I understand you and your situation a lot better now. Thanks for being honest and open. I’m not quite sure what will happen next. I’ll probably continue to gather more information before we come up with a plan. I’ll let you and your parents know about the plan. We will need your input on it. I might also talk to the principal.

FRANKLIN: That’s fine with me, but please don’t get me in more trouble with Mr. Bose or Mr. Mechant.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I understand. I’ll be careful.

Now look at Figures 9.1 – 9.4. You see that Franklin’s interview covers most of the points found on the Generic Child Clinical Interview. Clearly, the yield is greater than is typically garnered from surface interviews.

Interview of Dayna Madrid

Now let’s look at another case in which a clinical interview was used. This case involves a high school student named Dayna Madrid (Illustration 9.2). In Dayna’s case, background information had suggested possible depression. Dayna’s school psychologist, an experienced professional with a plan in mind as he commenced the interview, proceeded without a fixed interview outline. He simply counted on hid knowledge, topics that he routinely covers, and then flexibly following leads as they arose. Also note that like many psychologists, this psychologist does not employ a formal pencil-and-paper method of tracking case formulations (i.e., nothing like the HR Worksheet).

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Hi Dayna. Come on in.

DAYNA: Where should I sit?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Wherever you like. Ah, I don’t know about you I’m glad it’s finally Friday.

DAYNA: I agree.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well I guess that’s true of almost all students, except those who have a job that keeps them busy all weekend. Maybe for them Friday is not so great.

DAYNA: No job for me.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I’d like to chat for a few minutes but first I need to explain something. In general, what you and I talk about stays with me. But some information might need to be shared with other people involved in this evaluation. I’ll try to avoid sharing anything that might be embarrassing, and I won’t share anything with students or teachers who have nothing to do with you. The exception is if you tell me you might intend to hurt yourself or to harm someone else. Then I will be talking with your parents and probably with others to keep everyone safe.

DAYNA: Is this the same rules you told me about before I did that rating scale?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes, basically. By the way, I hope that filling in all of those questions wasn’t too much work.

DAYNA: It was a lot, but it was okay.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I think we have quite a few minutes to talk before your lunch time comes around. No real rush.

DAYNA: My lunch is at 11:15.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: You have first lunch then.

DAYNA: That’s right.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I guess I forgot which class you have right before lunch.

DAYNA: It’s U.S. history.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I wonder if you could help me understand a little bit better.

DAYNA: I guess I can try.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well, you already did a lot of work when you filled out the rating forms. I’m just interested in a little clarification.

DAYNA: Okay.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Well, one thing that you marked on the rating scale was loneliness. I wonder if you could clarify.

DAYNA: What do you mean?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: What does loneliness mean to you and when does it show up in your life?

DAYNA: Weekends and evenings. After I come home from school, I don’t have much to do and I don’t have anybody to do it with. I look at my Facebook and sometimes I post. But I don’t get very many likes and actually I don’t have that many (Facebook) friends.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: So, it sounds like weekends and evenings are boring, lonely, and may be disappointing. And maybe you wish you have a few more Facebook friends.

DAYNA: That’s right.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Pretty much every evening and every weekend?

DAYNA: Yes, at least since the start of high school, which is two years ago.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Sounds like you use Facebook as a way to make friends and connect with people. Try anything else?

DAYNA: I know I should, but sometimes I don’t have very much energy. I try a lot of things, but I get shot down. Some high school girls are vicious.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I see what you’re describing. Thanks for sharing. I’m guessing maybe this is why you marked the item about withdrawing (feeling like hiding) from others.

DAYNA: Yeah, that’s pretty much it. There’s not a lot of risk of being shot down when you’re home alone in your own room.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Hmmm.

DAYNA: It’s about three or four of them. They are always in the same spot. Anybody who walks by might get it. Comments and laughing. It makes you wonder what is wrong with me anyway. I hate to have to walk by those girls.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Ah, not good.

DAYNA: Really not good.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I see. So, sounds like part of your current feelings come from the way you are treated by some of the other kids.

DAYNA: Yes. Sorry, maybe I overreact. Maybe it’s as much me as them.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: No, I think I understand how you feel. It sounds tough. I sometimes hear the same thing said by other teenagers. But to change the topic just a little, you also marked that you sometimes feel as if you’re bad. Can you tell me what that means to you?

DAYNA: Well, I guess it means I’m bad at a lot of things but not a “bad-person” (she makes a gesture to indicate quotation marks). I try to be helpful and kind. I wish I could be better at stuff.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Better at stuff?

DAYNA: Not good at sports, not good at conversation, not good in school.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: How about being good at figuring out how to make things better in your life? Any ideas?

DAYNA: I don’t think so.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I want to be sure I understand. When you say things like that is that why you marked down on your form that you thought things would not get better?

DAYNA: Well, that is the way I feel.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Ah, I see.

DAYNA: I guess my teenage life kinda sucks.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Wow.

DAYNA: I get down in the dumps.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Sorry, is this often?

DAYNA: Not, not all of the time. Sometimes I go out with my friends, if I’m lucky, I feel okay.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Are you saying being out more often with your friends would lead to making things better for you? Maybe improving your mood?

DAYNA: Yes, for sure.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Now though, I need to ask you a question that some kids find a little bit embarrassing. Has anything awful or terrible or extremely frightening happened to you at any point during your life?

DAYNA: You mean really awful or terrible?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Yes

DAYNA: Being embarrassed at a dance doesn’t count, right?

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: No, these are more things like having been in the really bad car accident, been really sick and thought you might die, seeing a shooting, stuff like that.

DAYNA: No, not for me. There is a senior that I heard actually saw her brother get shot. At least that is the rumor. No, not me.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Listening to you talk, it sounds like you do become really sad.

DAYNA: Yes, I am sad a lot.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGISTs: Most of the time, most days?

DAYNA: I’m a little embarrassed to say yes.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Nothing to be embarrassed about.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I wonder if you could give me your estimate of just how big of a problem sadness might be for you.

DAYNA: A large one. Not overwhelming, not end of the world, but large.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Now, something important. You marked down that you sometimes feel like hurting yourself.

DAYNA: I wasn’t quite sure about that one. I read on the Internet about girls cutting themselves. They said it improves their mood. I was thinking about trying that.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Oh, I get it.

DAYNA: I only thought about it a little. I don’t like blood. I probably don’t even like pain. I decided no.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Okay, I need to ask you a few questions about possible suicide.

DAYNA: Okay, but I don’t think that’s me.

[The SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST then used the structured questions about Suicidality from the MINI-KID. Dayna disavowed intent to die, thinking about self-harm, a suicide plan, and prior suicidal attempts. Using the MINI-KID’s protocol, Dayna was rated as having low current Suicidality; see Sheehan (2010).]

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: I enjoyed talking this morning.

DAYNA: Okay.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: When we get all of this information organized, we will meet with you to let you know what we concluded. Our plan is to try to help you feel better.

DAYNA: Good.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: If you want to talk more or have any questions before we share a plan, please let me know.

DAYNA: Okay.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Any questions before you go?

DAYNA: Not really.

SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGIST: Have a nice weekend.

Rather than inquiring about an entire spectrum of potential conditions (or problems), the school psychologists concentrated on strong candidate explanations that he had formulated (perhaps consciously or perhaps counting on intuition informed by his own extensive history of assessing students). Whereas a tightly structured textbook diagnostic interview would have sampled across many candidate diagnoses, that was not true of the Dayna’s interview. In Dayna’s case, this turned out to be the presence of depression vs. “no real problem.” The school psychologist had already administered the BASC-3 SRP-A as a broad-band measure (note: he followed a sequence of assessment step slightly different than the conventional one). Although he examined composite indicators (i.e., the Behavioral Symptoms Index and the Internalizing Problems Index), the 12-item BASC-3 Depression scale was especially closely scrutinized. If he followed up with the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-2 (RADS-2), then another 30 items specifically concerning depression would have been available to characterize Dayna. It’s obvious that much is now (i.e., post-interview) known about Dayna’s prospect of depression. Perhaps follow up oral questions about depression risk repetition and assessment overkill. Perhaps skipping Dayna’s interview altogether makes sense. Perhaps not.

You can see how rating scale items and interview topics might fit together. In this case, Dayna’s BASC-3 SRP pointed toward depression. Accordingly, the school psychologist looked at depression items to help guide his interview. Strategies like this might clarify several points. Did Dayna actually grasp the meaning of each item that she rated? Are her self-reported feelings of unhappiness (i.e., those earlier endorsed on rating scale items) cross-situational and longstanding or present only in selected setttings and/or only at certain times? Does sadness appear only after failure or frustration (perhaps suggesting situational demoralization rather than pervasive depression)? Have major life changes occurred (perhaps signaling a transient adjustment problem). Are there changes, positive or negative, in interpersonal supports? All of these considerations go beyond mere symptom confirmation, although their discussion can easily follow Dayna’s rating scale responses, item-by-item. Equally important, school psychologists benefit from confirmation of an item when a student then goes on to elaborate. In other words, it helps to learn just what was meant when a particular item was answered as well as the thoughts, perceptions, and nuanced intensity associated with item-level responses. These are idiographic considerations springing from a largely nomothetic (standardized psychometric tool) foundation.

You are encouraged to practice clinical interviews. Working with a supervisor or senior colleague for feedback and suggestions often proves helpful. Devising your own form, following the Generic Child Clinical Interview or considering the hybrid option immediately following can go a long way toward helping you conduct an interview that extends beyond the mere superficial (i.e., helps you avoid a surface interview). That said, structure only goes so far. Skill development depends on practice, self-reflection, listening to others and becoming personally comfortable addressing the topics that comprise clinical interviews.

A Commercial, Hybrid Interview Tool, the SCICA

Somewhat more structured clinical interview options are also worth considering for routine use. An example is the ASEBA’s Semistructured Clinical Interview of Children and Adolescents (SCICA, McConaughy & Achenbach, 2001). Interestingly, the SCICA aligns with both idiographic and nomothetic purposes. Regarding idiography, the interviewer is guided through many opened-ended inquiries contained within broad domains such as:

- activities, school, jobs

- friends

- family relations

- fantasies

- self-perception, feelings

- parent/teacher-reported problems

Seemingly unique–and this constitutes the hybrid aspect of the tool–the school psychologist herself completes a standard array of rating scale items after the interview concludes. As one might suspect, derived scores are generated from these ratings. These scores are norm-referenced and judgments about individual students is informed by group level data (i.e., this aspect of the SCICA is nomothetic). Of course, school psychologists are sometimes interested in classifications but not in DSM-5 diagnoses. Structured (diagnostic-like) interviews might fit such classification purposes.

As a case in point, McConaughty and Achenbach (1996) used the SCICA to classify students into one of three categories: (1.) non-referred youth, (2.) youth with emotional-behavior disorders, (3.) youth with SLD. Tapping three separate samples, the authors confirmed high rates of correct classification relying on this standardized interview procedure. Of note, even though this study focused on group-level classification (a nomothetic consideration), the authors nonetheless talked about their interviews’ ability to detect important information that is in nature idiographic (concerns the individual). “For example, when parents and teachers report that a child shows severe aggressive behavior….the child interview can directly assess the child’s view of such problems. If the child reports little aggressive behavior, this implies limited awareness or denial of such problems, suggesting that behavioral interventions may be more effective than verbal therapies…” (McConaughty & Achenbach, 1996, p. 30). Other researchers concerned with classification (nomothetic perspective) and structured diagnostic interviews in actual cases similarly warn against forgoing valuable idiographic information (Leffler, Rebiel & Hughes, 2015). There is simply too much unique information to be learned from student interviews to confine their use to classification—either regarding special education categories or mental health diagnoses.

Specialized Interviews (neither Precisely Diagnostic nor Precisely Clinical)

What about very specific referral questions and very focused interviews? Consider some of the possibilities.

Threat Assessment Interviews

Sometimes school psychologists run across information during a generic clinical interview that suggests a student harbors threatening intentions. At other times school psychologists are consulted directly in the hope they will expertly assess a prospective threat. The latter represents a specialized interview much like the one that concerned a school psychologist you read about in Chapter 3, Emma Garcia. Despite the casual nature of the referral directed to Emma, judgments about threats (potential harm to others) should not be managed by simple intuition. In fact, specialized skills are required. What’s more, school psychologists are cautioned that these high-stakes evaluations should not be shouldered alone and should not rely on the skills and professional perspective of any one individual. Furthermore, a bit of knowledge about threatening behavior at school is required if one is to help conduct an intelligent assessment.

Consider just a few facts regarding the severe end of the school violence continuum, school shooters. Reeves and Brock (2018) provided essential information about various types of school shooters (i.e., psychopathic, psychotic, traumatized), various warning signs (e.g., fixation, identification warning behavior, novel aggression, last resort warning behavior), as well as risk factors that offer a modicum of predictiveness (e.g., social withdrawal, feelings of rejection, low school interest and limited involvement, a history of uncontrolled anger, access to firearms). Equally important, Reeves and Brock advocate for the preemptory creation of fixed school teams staffed by members ready to respond to potential threats of on-campus violence. These are referred to as “Behavioral Threat Assessment and Management” (BTAM) teams. Although BTAM teams are often led by school psychologists, the notion of a team, rather than an individual, is paramount. Specifically, Reeves and Brock propose that BTAM teams afford their leaders access to another mental health professional employed by the school district, a school administrator as well as an extra-school clinically-oriented mental health professional and law enforcement officers. Also important is the notion that threat assessments should never represent an end onto themselves. Rather, assessment arguably co-exist with school-wide violence prevention programs. This idea is advocated in a formal positions statement espoused by NASP (2015), a theme revisited in the paragraph below. In an ideal world, prevention efforts would not be confined to the risk of violence or its immediate causal antecedents. Rather, there would be an emphasis on system-wide mental health practices on the one hand and effective services for those judged at risk on the other hand.

This is all well and good. But the critical question necessarily remains how is essential information to be accessed, skills acquired, and threat assessment teams actually created? What about systemic prevention and intervention programs? Fortunately, focused school training and guidance are now readily available to deal with an array of school violence. Dewey Cornell, at the University of Virginia, has prepared a user-friendly, comprehensive manual aptly entitled Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines (Cornell, 2018). Equally important, workshops conducted by Dr. Cornell as well as those delivered by professionals trained by Dr. Cornell (i.e., a trainer-of-trainers approach) are readily accessed. The manual coupled with workshops aim to propel school-based adoption and widespread implementation. Congruent with a central theme of Cornell’s manual, explicit guidance via checklists and decision trees can arguably slow thinking, enhance decision making, and promote accuracy (i.e., invoke the Reflective System). For example, a decision tree helps teams work through various structured steps to arrive at one of the following judgments about each specific case:

- Not a threat

- A transient threat

- A substantive threat

- A very serious substantive threat

Guidance about immediately-required actions is indicated for the various threat levels listed above. Potentially more important, this approach is not concerned primarily with summary judgments (it disavows its ability to accurately predict execution of a threat). Instead, its chief goal is intervention, including systemic advocacy for primary (tier 1), secondary (tier 2), and tertiary (tier 3) efforts at violence prevention.

Thus, a continuum of procedures is advocated: those to benefit all students (e.g., school-wide conflict resolution), those for at risk students (e.g., social skills groups, short-term counseling) as well as those for students with very severe problems (e.g., intensive monitoring, special education services). A spectrum of interventions should predate any pressing threat assessment. This matches the PBIS approach that you will read more about in Chapter 15. The user-friendly nature of Dr. Cornell’s program is evident in clearly spelled out questions to address the threat plus a template for a “mental health” interview, which is often required. To help link assessment to treatment, a menu of intervention options is provided. Again, all of these features fit hand-and-glove with Cornell’s manual’s emphasis on rational, organized, deliberate assessment practices.

Happily, this program has been subject to empirical investigation. For example, among high school students, adoption of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines was associated with a 52% decline in the rate of long-term school suspensions (Cornell, Gregory & Fan, 2011). Across grades K through 12, program adoption promoted more therapeutic services concurrent with a decline in punitive discipline practices. Specifically, program initiation was associated with students receiving counseling services at a rate nearly four-fold higher than during pre-implementation, whereas alternative student placements dropped to less than 15% of their prior level (Cornell, Allen & Fan, 2012). Consequently, the “Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines” are now listed among the entries in SAMHSA’s National Register of Evidence-based Programs and Procedureshttp://www.nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=263

What does this all suggest to the frontline practitioners? Each school psychologist is urged to gain familiarity with her school district’s threat assessment guidelines. If such guidelines do not yet exist, she is urged to advocate for formal training for those in her district. Relatedly, efforts at team formation as well as explicit posting of policies and procedures are urged. Once policies and procedures are developed, they should be listed in a manner and location accessible to all of her colleagues.

Suicide Risk Interviews

Few school psychologists’ practices concern life and death—but this one, like threat assessments, might. Making judgments about suicide risk, as you might expect, is an intensively studied topic. Although there are interesting cutting-edge technological applications now emerging, such as brain imaging and assessments using virtual reality, these do not yet have clinical applications (Weir, 2019). Practically speaking, contemporary procedures for ascertaining suicide risk come down to long-used tools—direct youth interview (plus review of history and speaking with parents). There are arguably several ways to think about the nature and execution of suicide-related assessments in schools.

In one instance, the school psychologist operates no differently from her clinic-based counterpart. That is, she needs to be alert to the prospect of suicide risk in any youngster with whom she is working (thus the Generic Child Clinical Interview form that you saw earlier prompts that this topic is addressed). Any time an elevated risk is determined, the school psychologist needs to be prepared to drill down for additional information. You already saw the use of routine suicide risk questions during the interviews of Franklin (Illustration 9.1) and Dayna (Illustration 9.2).

Alternatively, a school psychologist might be conducting a routine evaluation when critical items a student endorses (e.g., on the BASC-3) indicate elevated suicide concerns. Specifically, three items from the BASC-3 concern wishing to be dead, wanting to die or wanting to kill one’s self. Follow-up inquiry to address suicidal risk is logically required when any of these items is endorsed (note: the Generic Child Clinical Interview form includes a check-off procedure to assure that critical items have indeed been reviewed and managed during each interview).